By d. emerson eddy & Zack Quaintance — Stephen Bissette — the legendary comics artists perhaps best-known for his work on Saga of the Swamp Thing — has illustrated a pair of brand-new pages for a Kickstarter comic called The Golem of Venice Beach.

And as the kickstarter campaign prepares to wrap later today, The Beat has a wide-spanning conversation with Bissette, covering everything for what inspired him to do this new work, his thoughts about crowdfunding in general, using realism to enhance the fantastical, and much more.

Interview: Stephen Bissette

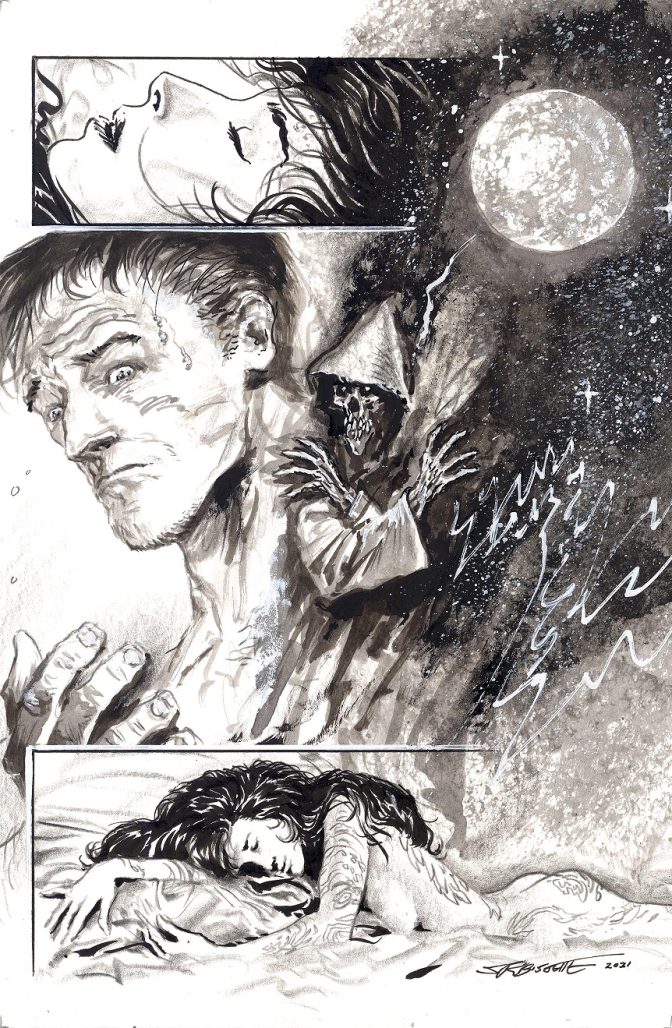

THE BEAT: So, first things first, what can you tell us about the new work you’ve done for The Golem of Venice Beach, which the project’s promotional materials describe simply as “an eerie phantasmagoria”?

STEPHEN BISSETTE: I’d retired from the American comics and graphic novel scene back in 1999. In early 2005, James Sturm invited me into the soon-to-open Center for Cartoon Studies, and by summer 2005 I was co-teaching at the first summer workshops and by that fall teaching full-time at CCS, where I continued as an instructor until my retirement in 2020 (not due to the pandemic, but a pre-planned departure due to the fact I turned 65 that year).

So, long story short, having worked intensively with a new generation of cartoonists year after year at CCS, while writing (non-fiction primarily, some fiction) has been my main published creative outlet since 1999, I wasn’t sure if I still had the drawing chops to dive back into doing new comics work. As noted, I’d done some work since, but nothing particularly ambitious; when you’re teaching, there simply isn’t much time for anything else, and those fleeting summer months are a pretty tight window of opportunity for tackling anything of any scope. Once I retired from teaching summer of 2020, I thought it might be a good idea to test my skills anew.

There was a mode of painted wash and collage black-and-white comic art I’d really, really gotten into back in the 1980s—stories for Scholastic Magazines Weird Worlds run, “Kultz” for editor Archie Goodwin (Epic Illustrated #6), “Into the Shop,” “A Frog is a Frog,” “The Blood Bequest” for Marvel’s Bizarre Adventures—that I’d grown exasperated with due in part to the crappy printing Marvel used on Bizarre Adventures at the time (unlike the pristine reproduction Scholastic and Epic offered), and completely abandoned once I got involved with the (aborted) Marvel Titan Science series and penciling as part of the Saga of the Swamp Thing creative collaborative. As with the various book illustration gigs I’ve done since the 1990s, I love to challenge myself with new tools and techniques appropriate to every job, and the “eerie phantasmagoria” free-for-all of The Golem of Venice Beach prompted my decision to dive back into how I used to paint comics pages prior to 1983.

Did I still have the chops? Well, you look at the pages, you decide. I think they worked out OK.

THE BEAT: How did you come to be involved with the project, and what drew you to contribute to The Golem of Venice Beach specifically?

BISSETTE: Over the years I’d done various comics projects with the CCS students and alumni, including published interior narrative stories for their anthologies. I’d also contributed an original comic story to my son Danny’s zine, and Danny and I cooked up “An Alphabet of Zombies” for the UK publishers of the anthology Zombies. But as far as doing any new pro comics work for American publishers, I’d only stepped out of my retirement from the American comics industry for friend Cayetano “Cat’ Garza’s Secrets and Lies anthology and for editor Chris Duffy (for Spongebob Comics and Above the Dreamless Dead).

Now, among the CCS projects I was invited into was Sundays, an oversized anthology the CCS class that Chuck Forsman, Joe Lambert, and Alex Kim were part of. If memory serves, Chuck, Joe, and Alex pulled the first issue of Sundays together for the then-upcoming winter NYC comics convention, and I worked up a semi-satirical S.R. Bissette’s Tyrant® one-pager “Tyrant Dreams” for that first issue, a Mad-style parody of “Casey at the Bat” ending with a Little Nemo in Slumberland gag panel. Chris Stevens somehow saw or read that piece, and asked to include “Tyrant Dreams” in his crowdfunded first edition of Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream, which is how Chris and I first connected. For some reason, “Tyrant Dreams” didn’t make the grade into the trade edition of Dream Another Dream, but hey, that’s comics.

Years later, Chris Stevens reaches out to me to see if I had any interest in being part of the crazy-quilt or tapestry (choose your metaphor) of multiple artists working on the singular graphic novel The Golem of Venice Beach. Usually, I just say ‘no,’ since these kinds of invitations almost always involve a commitment to a total spec project—work for free, thus “investing” in a project not of one’s own invention, something I just don’t indulge in, as I’ve plenty of my own projects I’m not paid to work on, thank you very much—but Chris and Chanan Beizer had thought it through professionally and were offering a generous payment rate, the only time anyone’s offered such a thing since Chris Duffy had invited me in to play in his projects.

So, in a nutshell: enticing invitation, from an editor who had treated me fairly on an earlier project, with a fair page rate on the table, a subject matter already of great interest to me (the Golem; I’ve been fascinated with the archetype and legend and films since first seeing photos as a kid in Famous Monsters of Filmland of Paul Wegener in his German silent classic films), and a retirement-spawned window of opportunity, and a hankering to challenge myself anew.

I’d also been invited by another good friend, John Jennings, to collaborate on a future project (which we’re now working on actively). “Could I do it?” I wondered. Completing my contribution to The Golem of Venice Beach was me proving to myself, “yes, I’ve still got it, I can still do this.”

THE BEAT: You’ve had experience in numerous forms of comics publishing, working within the corporate system to self-publishing, do you feel that crowd-funding has changed opportunities in publishing in any way? Whether creatively or in the breadth of types of comics that can be published?

BISSETTE: Crowdfunding has changed everything. With the implosion and utter collapse of the once-viable Direct Sales market in 1996, consolidating into a monopoly (Diamond Dist.), and over a decade ago the termination of Peter Laird’s essential Xeric Foundation involvement with bankrolling selected independent comics creator efforts, I really feared for our Center for Cartoon Studies students and alumni. How would they get their feet wet in such an insular, bottle-necked industry? Crowdfunding in all its myriad forms didn’t just “take up the slack,” it revolutionized how comics and particularly graphic novels were being published. I recall the first couple of CCSers who experimented with the crowdfunding models that existed in the early 2000s, and I recall the first students in our classrooms who arrived already successfully crowdfunding the work that got them into the school in the first place. I also recall meeting our first crowdfunder superstar—undertaking the two-year CCS program having already “scored” as a successful crowdfunder pro—who was as polished, humble, and professional a cartoonist as any I’ve ever had to pleasure to meet or work with. Crowdfunding platforms like Patreon offer lifelines unlike anything that ever existed before in my professional lifespan: I love, love, love the fact that my wee little monthly contribution is part of the revenue stream that affords creators like Melissa Mendes (Freddy Stories, her excellent serialized biographical graphic novel The Weight) and Charles Forsman (The End of the Fucking World, Revenger, I Am Not Okay With This, etc.) a means to just keep making their comics. Nothing like it existed in the 20th century, and it’s an innovation and means for anyone to assist in subsidizing the work of creators whose efforts bring their readers pleasure.

I won’t go over how comics and graphic novels were created, funded, published, distributed “in the old days,” suffice to say most forms of crowdfunding consolidate some of the craziest and most dysfunctional aspects of the Direct Sales market system into a more cohesive and consumer-targeted system. It’s quite eloquent, really: the crowdfunding process rolls up bankrolling, marketing, and distribution into a single (but massive) undertaking. Thanks to my 15+ years at CCS, I witnessed how it could work, how it did work, and at times how it didn’t work: like any system, there are pitfalls and unplanned consequences that can prove discouraging and/or daunting, to say the least. But I’ve also seen how it can and does work, happily have seen some truly successful ventures realized, and it’s also been heartening to see peers of my generation like Michael Zulli (The Fracture of the Universal Boy) and peers I taught with at CCS like Alec Longstreth (Basewood) working with crowd-funding to realize dream projects no publisher would have undertaken, much less adequately funded, much less executed in the handsome editions that are now on my library shelves. Some truly extraordinary work that never would have otherwise seen print now exists, thanks to crowdfunding, and in some cases the creators earned what their labors deserved.

That duly noted, I’ve also seen the downside, including kicking in on crowdfunded projects that were funded but never delivered. As a comics historian (I taught comics history at CCS for my 15+ years), however, there’s another downside that’s been apparent to me from the beginning: crowdfunding is spawning a vast ocean of incredible work (and some less-than-incredible work) that will be essentially lost to time in the blink of an eye. I can’t count the number of crowdfunded projects I learned about after-the-fact, and there was no way to purchase or find a copy after the crowdfunder was over: understandably, the creators print-to-order, avoid overprinting, and there’s no other venue of distribution open to them afterwards in any case. So, a lot of key works—or what might have been considered key works, were they accessible to future generations—have been out of reach the minute the clock ran out in the fundraiser. They are then further out of reach a week, a month, a year later, and completely out of reach, out of mind, out of collective or individual memories, a decade later. I’ve already seen it happen, and this means this current revolutionary and evolutionary gestalt in the comics and graphic novel forms is already impossible to summarize, to synopsize, to study, to grasp.

That’s both exasperating and exciting, but I can’t see how anyone would or could afford, much less track and find, everything of merit that’s been crowdfunded ten years ago, five years ago, last year, or is being crowdfunded right now. It’s going to be…interesting. It’s going to mean future histories of the medium will inevitably fall short once they get to this new Millennium we’re in.

THE BEAT: Horror often figures prominently in your work and collaborations with others, though there’s always a sensitive heart beating behind the monsters. From the misunderstood heart of Swamp Thing to even the survival ethos in Tyrant. How do you reconcile the two extremes of fear and love?

BISSETTE: Hey, that’s life. “The two extremes of fear and love” pretty much gets right to the core of existence, for me. In anything I do, creatively, I try to get to and express the primal core of the subject at hand; that’s what I tried to do for, and with, my fleeting contribution to The Golem of Venice Beach, much as I did back in the 1980s when Peter Laird and Kevin Eastman invited me to write and draw my own Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles story for the Turtle Soup anthology (the story was “Turtle Dreams”—do you detect a consistent theme here?). I tried to grasp, then express graphically, the “two extremes of fear and love” central to the Turtles’ bond with Splinter, and Splinter’s bond with the Turtles. I tried to do the same with and for Swamp Thing, and was fortunate in that I found myself in like-minded company with John Totleben (who was onto the process with Swamp Thing before any of the rest of us), Alan Moore, and Rick Veitch.

So, I pitched a bunch of ideas about the Golem concept to Chanan and Chris after deciding to work with them on a page or two. I wasn’t sure what they were looking for from me, or how I might fit into the tapestry they were weaving (in terms of narrative and imagery, image-flow), but I understood and was eager to explore some essential aspect of the Golem archetype. My ideas didn’t perch, so to speak, but once they came back with the springboard of the Golem and the tattooed woman making love, I could see a number of instant possibilities, and when Chris sent me the design of the death figure tattoo on her back, it all came to me in a rush. “The two extremes of fear and love” were right there, all I had to do was work out the flow (thankfully, Chanan was open to my spreading the sequence over two pages) and work within the start-and-end points they predetermined were necessary for my sequence to fit into their narrative. I’d read Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man when I was 11 years old (and I’d long ago as a pre-teen loved and memorized the Groucho Marx song “Lydia, the Tattooed Lady” from AT THE CIRCUS; “…you can learn/a lot/from Lydia!”), which also provided instant inspiration.

THE BEAT: Whether inking yourself or being inked by other legendary artists, there’s always a depth and detail to your linework, a beautiful marriage of realism and surrealism when it comes to subject matter. How does realism in art enhance the more fantastic, otherwise unbelievable elements in a story?

BISSETTE: I suppose it grew out of a childish fixation to make my dinosaur and monster drawings “look real” to me from the time I was a four-year-old scrawling on butcher’s paper and newsprint tablet pages. Much as I loved, love, and was and am still bowled over by comics by artists like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, the cartoonist whose work I really adored and studied and copied from a tender age was the late, great Sam Glanzman’s comics pages and panels. Sam had a way of making everything look “real,” living, lived in, and it not only looked real to me, but Sam made it tactile in a way no other artist had before or has since. This also meant there was a somewhat pedestrian, ordinary look to his characters, his people, but that’s how people looked to me, too, as a kid: ordinary. By wedding the ordinary with the extraordinary in his imagery for comics like Kona, Monarch of Monster Isle and Hercules, Sam made the uncanny look and feel believable, alive, plausible, and I’ve always strived to emulate that aspect of Sam’s artistry.

It was also an essential element in two other artists whose work inspired me from a tender age: Charles R. Knight’s paleontological paintings and reconstructions of prehistoric life, and Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion-animated creatures and sequences for films like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, 20 Million Miles to Earth, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Jason and the Argonauts, and so on. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was among the first movies I ever remember being captivated by on television, and Harryhausen’s work—like Glanzman’s comics work—relied upon convincingly fusing the impossible and the mundane real world into what Ray referred to in interviews and his writings as a “reality sandwich.” In my artwork, I try to make that “reality sandwich” a seamless synthesis of real-and-unreal, the familiar and the unfamiliar co-existing and alive as one.

While there are a lot of far more stylized artists whose creations I respond to—Willy Pogany, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Joe Kubert, Greg Irons, Mario Bava, Sergio Leone, Karel Zeman, and countless others—whatever I pirate from them or carry from their work to my own is subservient to the formative early influences of Knight, Glanzman, and Harryhausen. It’s hardwired into my head and hand, it’s organically and biologically part of my nature: how I see, how I express, the world that’s in my head.

Or, in the case of The Golem of Venice Beach, the world that’s inside of Chanan’s head that I hope I’m adequately channeling onto the page via ink, wash, colored pencils, white-out on Bristol Board (oh, yes, I work by hand, on paper, still; I don’t work digitally, save to scan and clean-up the pages or illustrations for delivery to a client).