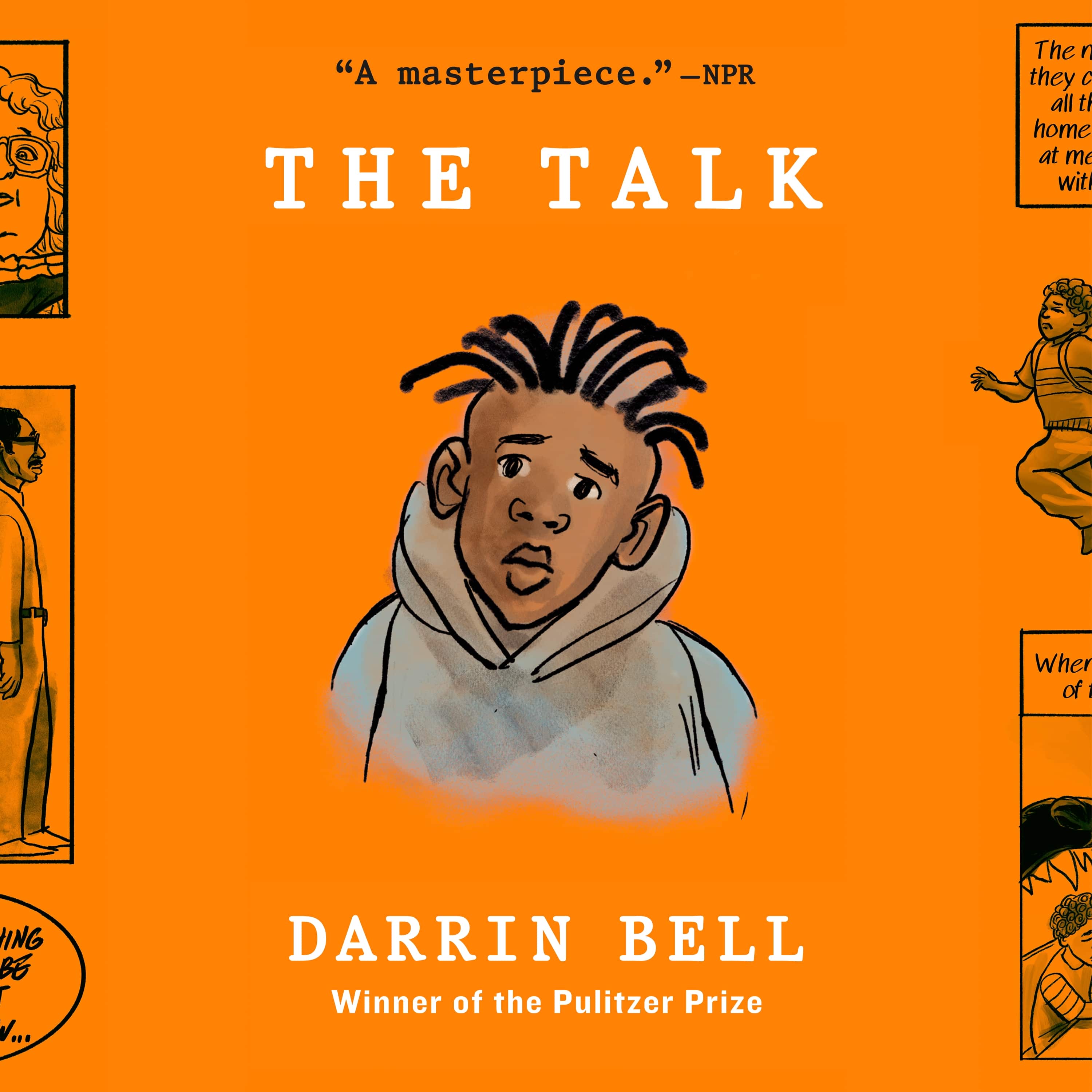

On August 27th, 2024, the audiobook adaptation of The Talk by Darrin Bell will be released. The Pulitzer Prize winning cartoonist’s graphic memoir was originally released in June 2023. But now, The Talk is being released in a new format.

The adaptation from Macmillan Audio features narration by Bell, his son Emyree Zazu Bell, Brittany Bradford and William DeMerritt. In anticipation of the adaptation’s release, Comics Beat was honored to catch up with Bell over Zoom to learn more about the audio adaptation of The Talk.

AVERY KAPLAN: The Talk has had quite a journey! Can you tell us in your own words what the book’s path has been, from genesis to this audiobook adaptation?

DARRIN BELL: The path has been more than I expected. I thought I was just going to put my story out there, and people would read it and either it would resonate with them or not. And some people might be able to use it as a tool to give their own kids The Talk, or to build empathy with people who don’t really need to have The Talk themselves but would like to know why such a large segment of the population does have to have The Talk.

So at first, it just began as a conversation between me and my editor during the whole summer of protest after George Floyd was murdered. I just wanted to say something that spoke to what was going on. Something that would explain why I cared so much about it.

I mean, I had spent a decade chronicling instances of police brutality and murders and white supremacist murder of unarmed Black people. And the response from people who agreed and who cared was heartening. But then there was always the response from people who felt that all these people had it coming somehow. And that never changed, until what happened with George Floyd.

The nation was in the middle of a pandemic, and we were all on lockdown, and that video was everywhere. And it was undeniable what was happening in that video. All of the sudden, there were millions of people whose minds were a little bit more open to the possibility that it’s exactly how Black people have been telling them it has been all along.

So I wanted to create something that would speak to that. And it would show multiple instances in my life where there were microaggressions. And then there were some more perilous instances where if things had gone a little bit differently, I wouldn’t be here today.

I could’ve ended up like Tamir Rice. Or the police officer that pulled us over when I was in college might have ended my life, if it hadn’t turned out that I was a security guard and my supervisor was someone he knew.

So I just thought I was telling my story. And I thought that would be the end of it. I didn’t think a year later people would still be talking about it. And I did not think I would be asked to adapt it to audio.

Especially because it’s a graphic novel, and I had never heard of audio versions of graphic novels before. I didn’t know how it could work. Until I read the script. It was really faithful to what I drew. And once I read it I thought, of course. All you have to do is kind of describe the action that the images are showing.

In the process of recording it, I was doing the audio, they hired a couple of voice actors, and my son voiced his own dialogue. Which was an amazing moment for me.

But in that process, I realized that this is kind of like a black box play. I don’t know if you’re familiar with black box theater, but there’s anywhere between one and five actors, and just a stripped-down stage. It’s usually black, and just a few props to hint at what the setting is, and it’s in a really intimate setting. It really focuses people on what’s being said. And this was just like that, like an audio version of a black box play.

So I’m thrilled to see the story can live in more than just one medium.

KAPLAN: While you read parts of The Talk, there are other readers too, including your son. What was it like working with family on this adaptation?

BELL: Well, it just felt right, because I wrote the book for him. When I was talking to my editor, I told her, “You know, right now everybody cares about this. But by the time I’m done with this book, there’s going to be the usual backlash against this.”

Every time the moment of racial reckoning and awakening… Whether it was Reconstruction, or whether it was World War I when they saw all these Black soldiers coming home, or whether it was when they saw prosperous Black towns sprouting up throughout America, or the Civil Rights movement, or affirmative action…

There’s always been one step forward and ten steps backwards. Because white supremicists just lose their damn minds, and they work overtime to gaslight the nation and make it seem like any movement toward equality is taking something away from them.

So I told my editor, I’m basically just going to write this book for my son and my children. You know, you never know what happens in life. If I’m not around when they’re older and they need to be given The Talk, I’ll still be able to give it to them, all they have to do is open my book.

It was a family thing to me. I was telling a little bit of family history for my son. So when I was sitting in the recording booth with him, it just felt like, “Of course. This is totally natural.” And no one else could have done the dialogue… I mean, the voice actors could have done it, but it wouldn’t have been him.

KAPLAN: I am curious if adapting The Talk to the audiobook format altered your perspective of the work at all?

BELL: My perspective? You know, I went into it wondering if that would happen. That was one of the exciting things for me. I worked in solitude on this graphic novel for over two years, and now I was going to get to work with three or four other people: the script writer, the voice actors and the director.

I was excited to see if they would bring something different to it, some other interpretation to the work. I don’t want this to sound like a slight towards them, but: no, there’s nothing at all different about it. It’s the same story just told a little bit differently. But it hits all the same points, it conveys all the same messages as the artwork did. And I’m still astounded that they were able to do that, with the script and with the audio that they added.

I worked really closely with them on the sound effects and on the musical cues. It felt natural. Because when I was creating the graphic novel, I thought of it cinematically. Almost like I was creating a film in my head and trying to capture it on paper. So this helped me flesh out that film that I had been thinking about.

In the graphic novel, I was able to capture the visuals of the film. And then when I got to do the audiobook, I got to bring the other part of it out of the my head: the sounds and the tone.

I don’t think it gave me a different perspective, I think it just completed the experience for me.

KAPLAN: The Talk is a book that runs the emotional gamut. I’m curious if there were any parts that were especially difficult (or conversely, especially easy) to express?

BELL: The difficult parts were the things that I had been, I wouldn’t say I’ve been struggling with my whole life, but things that I had struggled with at the time and had tried to suppress; tried to forget for the rest of my life.

Like the incident with the police officer. I spent a lot of time as a child feeling shame about that incident. You know, I had so many conflicting feelings. You’re told police officers are the good guys, and a lot of the movies and TV shows I watched — like CHiPs — the cops were the good guys. So I just had this internalized sense that because of what happened with the cop, I must be the bad guy. And that was hard to get over, to get past.

But I managed to forget about it, until I had to do this book. And I didn’t think it would be so hard until I drew the encounter between me and the cop. All of the sudden it felt like I was back there. I relived the same feelings I had at the time. And that was the first time that I realized that this book was going to be really hard for me to complete.

Because, and I touched on it in the afterword when I brought in the Star Trek analogy and talked about how you don’t only exist in the present, you also exist in the past. I realized when I did this book, that when I got to each of these chapters, I was going to be transported back to my younger self. And I was going to feel the same things that I felt back then.

So that was difficult. There was also the chapter in Gemco where I was being profiled by somebody and I did not want my mom to make a big scene about it. And she did and I was humiliated and I was resentful and I couldn’t stand that she did it. And I held it against her for quite a while. It wasn’t just that scene. There were plenty of other instances that didn’t end up in the book. But they were instances where I took what my mom did for granted.

And as I was doing that chapter, I relived the feelings I had as a kid. But I’m also an adult, I’m a parent, and I was looking at it from that perspective, too. So I felt a lot of shame for how I felt about my mom as a kid and how I didn’t thank her until decades later.

And then the chapters with my dad. Those were difficult for me because I’m a little older than he was at the time. And all my life, I thought that he didn’t give me The Talk — not just that talk, but he didn’t talk to me about anything serious. Whenever I tried he would turn it into a joke just to avoid having deep conversations with me. All my life, that made me think my dad just didn’t care about me.

But again, I’m a parent now, and I have kids who are the same age that I was back then. And I know that there are things that are hard for me to talk about with them. But I do, because my dad didn’t, and I know how that made me feel. So I talk to them about whatever they want to know.

But I still have, when they raise something uncomfortable — something that I feel like if I explain it to them its going to take away some of their innocence, and I don’t want to do that — when I got to those chapters with my dad, I couldn’t help but feel that maybe that’s what was going on with him.

So that was difficult for me. Because as I was drawing it, I was thinking, “Man, I wish I could go back in time and not have any of the resentment and the estrangement and all that, and just try to understand him better instead of just focusing on what he’s not giving me in terms of support and knowledge and insight.” I could have tried to understand why.

And then I could have just hung out with him, and maybe not talked about that stuff and just said, “Hey, dad, let’s go see a baseball game or something.” Instead of spending years not talking. So when I did those chapters, that’s why that was difficult for me was because there was so much regret.

But also, at the end of it, with all the regret and all the wishing I could change things, I also got to draw myself as a small child and as a teenager who didn’t really have the same perspective on things that I have now as a parent. And I got to look at myself objectively and think, “Man, you were little. You can’t be expected to know everything that you know now.”

So while it was difficult, it was also cathartic. It let me let go of all those things after. I had to feel them while I was doing the book but then I was able to let them go.

KAPLAN: Do you consider your political cartoons distinct from your sequential graphic narrative work?

BELL: Yeah. I try to do each project differently. Partially because I’ve been doing this professionally since I was 19. And I don’t want to get bored. I don’t want to burn out. I saw multiple artists burn out when I was growing up, and I thought, “That’s not me.”

So I want to challenge myself to have different styles and different approaches. I approach Candorville totally differently than I do my editorial cartoons, and The Talk was a whole other thing, too.

I never really feel like I’m in a rut, because I have multiple projects going with different styles. So whenever I feel like, “Okay, that’s enough of that for this week,” I just move to the next thing.

Sequential art is very different. It’s a lot more subtle than single-image editorial cartoons. Because you don’t have to make the point in one image. In fact, you don’t have to make the point that people are expecting you to make.

And I think those are the best comic strips: when I start to make one point, and people think they know where it’s going, but then in the fourth panel it turns into something else entirely. I love doing that. And I love surprising people, and surprising myself.

That’s the fun of it. I never have a punchline in mind — purposely, I don’t have a punchline in mind. I just have a conversation in mind. And I have the characters have a conversation, and I let them take it where it’s going to go. And I’m often surprised by what my own characters say.

I wasn’t in the beginning. That’s not how it is in the beginning. In the beginning, when you first start out, you feel like you need to have a lot more control over where it’s going. You think a lot about what kind of humor. You might study other cartoonists and think, “How do they get their points across?” Stuff like that.

But after a few years of doing it — and I’ve been doing Candorville since high school — it’s been syndicated since 2003. Your characters, through their interactions, take on a life of their own. And when it comes time to do a new comic strip, I don’t really feel like I’m constructing something so much as I’m visiting with them.

With an editorial cartoon, every once in a while I do multipanel ones. And I enjoy that too. But I usually try to convey a single idea in a single image. Comic strips let you convey multiple ideas, but editorial cartoons you really need to hammer the point home as soon as people see it.

A lot of cartoonists who do single-panel cartoons are basically gag cartoonists. I don’t approach it that way. I don’t think an editorial cartoon needs to be funny. I think it could be funny, it’s always good when it is, but when issues are really serious, you could have a really serious image. All it has to do is seem truthful. It has to bring out some truth that a lot of people are overlooking.

To me, that’s the difference.

KAPLAN: Do you have a favorite Star Trek episode?

BELL: Trying to narrow it down… I have a few. They’re all Deep Space Nine. There’s “In the Pale Moonlight.” I loved it. The ending was so chilling… the last three seconds. That was twenty years ago and I still get chills just thinking about it.

And then there was “The Siege of AR-558.” It’s the one where they’re on a planet, the Defiant wasn’t even supposed to be there — I think they were just bringing them some supplies. But there were reinforcements that were either delayed or killed or something. So they stayed to reinforce the people who were there. It’s the episode where Nog lost his leg.

Just watching all these characters that I had been watching over the course of six seasons be thrust into what I imagined — because I’ve never been to war — but what I imagined was and seemed like to me to be a really authentic and accurate wartime experience. And all the jokes, all the subtext and all their side stories over the past several years all the sudden were stripped away and didn’t matter.

And even Quark rose to the occasion. I can’t think of Quark defending his wounded nephew from the Jem’Hadar without… You know, this is ridiculous, I know, but without tearing up every time I think of it.

And there was The Next Generation episode, “The Offspring,” directed by Jonathan Frakes, where Data created a daughter. Pretty much anything Frakes is amazing. He even made some great Discovery episodes. I mean, I liked a lot of Discovery, but the ones he was involved with were the best.

So it’s hard for me to pick a single favorite episode.

KAPLAN: Do you personally believe that the social utopia depicted by Star Trek can be achieved in humanity’s future?

BELL: Before I get to that, let me amend my last answer. There’s an episode of Deep Space Nine, “The Visitor,” where Jake loses his father. And then he tries in vain to get him back over the next several decades, until he finally does.

When I saw it as a kid, I liked it. But now that I’m a father, it hits totally differently. And I can’t make it through that episode without breaking down.

Because I picture my son as Jake. When I first saw it, I pictured myself as Jake. But now I picture my son as Jake. And the thought that a son could love his father so much that he’d spend the rest of his life trying to get that back. I don’t know if my son would do that, but the thought of it is very, very touching.

And it gets to the heart of what made Deep Space Nine special, which was that it was an incredible family show. The bond between Ben and Jake was just so different than anything else Star Trek has done.

As for the social utopia. I used to believe that old quote that Martin Luther King, Jr. popularized, but I think it was around much longer, about how the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice. I’m not too sure anymore.

When you look at the truly long arc, most of human history has been abysmal. It’s been totalitarianism, it’s been tribal warfare. It just might turn out that the Enlightenment and the democratic governments that sprung from that are not an evolutionary destination. They might turn out to be an aberration. And they might fade into history.

There’s a better than even change that that’s what’s going to happen, judging by what’s going on all around the world. It’s not just in America, its in Europe. Even New Zealand just turned right.

So I don’t know. I don’t have a whole lot of hope that that’s going to happen. I mean, I wish it would. And I think if we make sure that our kids and the next generations keep watching Star Trek, it will engender a desire in them to make that happen and they might be able to do it.

I don’t have any illusion that it’s going to happen in my lifetime anymore. I thought it might when I was a kid. Because when you’re a kid, you think you’re going to live forever. You’ll be able to see aliens and go to other planets and stuff. I think there’s a better chance that we’re going to meet aliens in my lifetime than there’s going to be peace on Earth.

KAPLAN: The Talk was originally published in 2023 and will be re-released in audio on August 27th. However, I’m curious if here in the first week of July you have any thoughts you like to impart to readers in light of current events.

BELL: Well, current events are not just current events. It’s more of the same in this country. Democracy is fading away. As I said, social progress is being turned back. This isn’t a new thing, it’s part of a pattern. It’s the whole reason we have to have The Talk to begin with.

Kids have to know and they have to learn at an early age to look out for it. To know that there are forces in this country that do not want them to succeed. They have to learn how to succeed despite that. They have to learn how to recognize when people are good faith actors and they just don’t understand, or when people are bad faith actors who are operating out of malice, and who are just looking for an opportunity to put them in their place. In the place that they want them to be in.

They have to be able to tell the difference between people who are worth having conversation with and people whose minds can be changed. Who are just ignorant and need to learn and be in the presence of people who are not like them. The difference between them and people who don’t want them to exist and don’t want their stories to be told.

The difference between people who just haven’t read books like The Talk and people who are actively trying to ban books like The Talk to keep other people from reading it. Because there afraid that it’s going to engender understanding and build empathy.

You know, even the leaning toward authoritarianism in the county is nothing new. The south was a democracy until Black people were able to vote. Then it because authoritarian. And it stayed that way for a hundred years. That’s happening now on a national scale. Demographics are changing, white supremacists saw that democracy wasn’t serving them anymore because by 2040, they weren’t going to have the numbers to vote away civil rights. Or to vote away progress.

So they’re abandoning democracy. Instead of trying to persuade people, they’re trying to keep people who disagree with them from voting. And that’s all part of The Talk. You have to be aware of why people are doing that. It’s not an accident that voter ID laws and other impediments to voting all impact Black people disproportionately. It’s not an accident. And if you’re not on the lookout for that, and if you’re not away that that’s the motivation that a big part of society has, then you’re not going to be able to fight it.

People need to have The Talk. And if it’s too hard for them to have, like it was for my father, now there’s this book. Just hand it to your kids and be there to answer any questions they have.

The Talk is available in audiobook format beginning today.