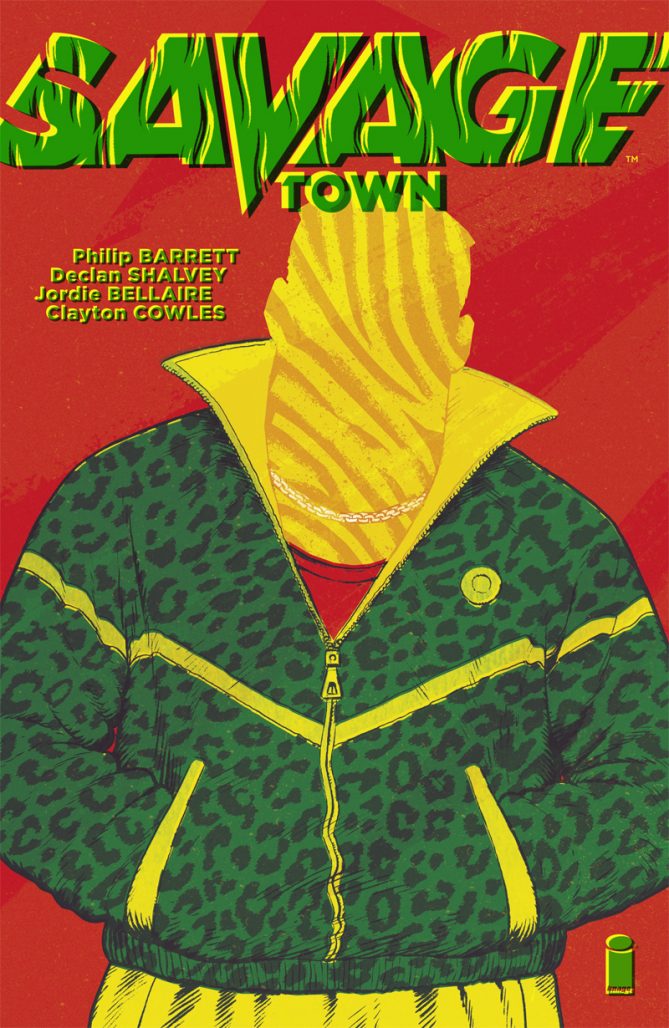

Recently, the Beat had a chance to sit down with Savage Town writer Declan Shalvey. Best known for his artistic work with Warren Ellis on Moon Knight and Injection, Shalvey is outspoken about helping comics illustrators get the credit they deserve from critics and fans. In this second part of a two part interview, Shalvey discusses the themes and ideas behind the story of Savage Town. We also discuss the story’s historical inspirations and the controversy the book’s release has caused in Ireland.

This interview contains spoilers for Savage Town.

Lu: To me at least, the point of reading stories is to expose yourself to something that you haven’t seen before. I think Savage Town does that. I think that we get the occasional Irish or Irish-American character in American media, but we rarely ever get to see Ireland itself.

Shalvey: When I read Preacher and saw Cassidy in it I was like, “Oh, cool an Irish guy!” I always get a kick out of that kind of stuff.

It was the same with Injection. Bridget is Irish because that’s one thing I asked for; if there could be an Irish character. Getting to draw Dublin in the first couple of issues was really cool. It felt really good to do something that felt like it was coming from where I’m from, you know? We’re at an age where everything is about representation– and I’m not saying that more white people need to be represented from Ireland– but I remember what [seeing people like me in media] felt like as a kid and I’m fortunate that I’m in a position where I could maybe add something to the mix. It feels really good to have done it, for better or worse, we’ll see what it does. It’s been really rewarding, I have to say.

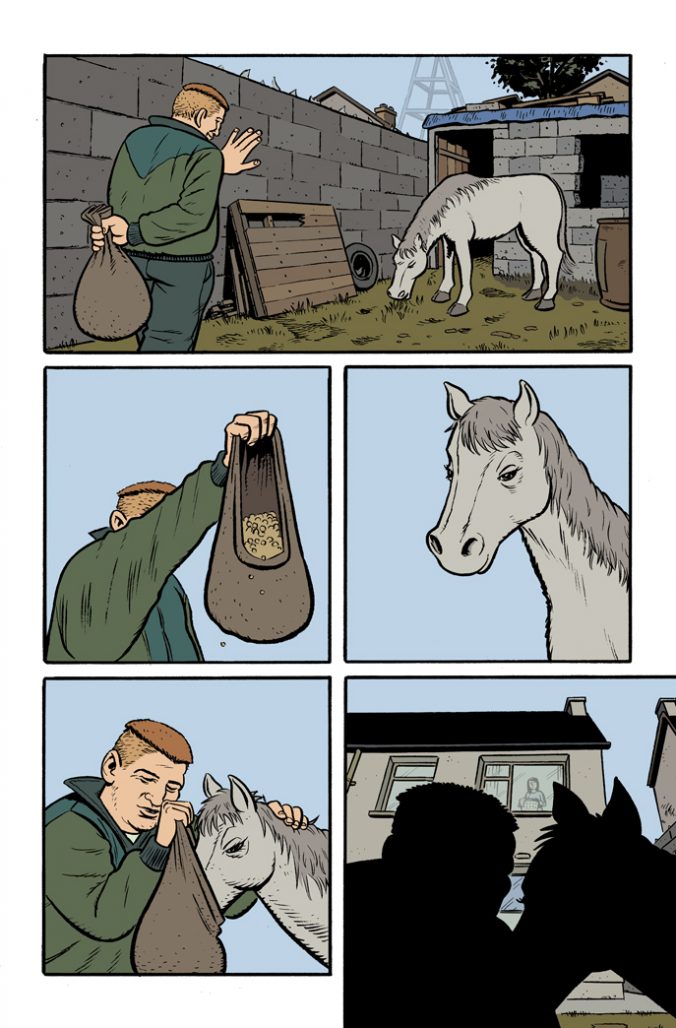

Shalvey: He’s not Romani. I didn’t want to expressly say it in the book as such, but we here in Ireland have a small culture of what we call Travelers. The slur for them is knacker, so when you hear someone called knacker in the book, that’s kind of like saying the n-word, effectively. It’s the same kind of connotation– it’s an ugly way to describe them.

It’s funny: Jordie described Redlands as a love and hate letter. That’s kind of how Savage Town is for me. I love so much about Ireland, but there’s stuff I definitely would be critical of. I think there’s a hypocrisy in racism here. Blackie clearly is treated different because he’s black, but in a very, very direct way, to his face– it’s actually quite honest. It’s not good, but it’s honest. The only thing that’s different about him is the color of their skin…they treat him just the same as anybody else. He’s very much one of the guys in his gang.

That is an ugly side of Ireland that I felt should be seen, you know?

Lu: Sure, absolutely. I think it sort of adds a lot to the story that our two leads come from this sort of outsider perspective.

Shalvey: That’s a reason why Jimmy’s so protective of Blackie. There’s a bit where a character is pretty racist towards Blackie and it’s kind of a funny moment, but that kind of speaks to how Jimmy is very protective of Blackie and it’s not because they’re the same as such, but [because] they have the same problems.

Lu: The story of Savage Town is based around real life events, right?

Shalvey: Yeah. Savage Town is a story that’s about crime but it’s also about Ireland. If you notice in the book, there are lots of scenes of cranes and construction happening. That’s because the story takes place at a time, back in the early 2000s, where Ireland was going through this thing called the Celtic Tiger. A massive amount of economic wealth was coming into the country and everyone became rich. But it was a bullshit term for a bullshit period. The Celtic Tiger was basically an economic bubble. But Ireland has traditionally been a very poor country, so for us to have money…we were all like “woah!” We were all happy…except me because I was a poor art student at the time.

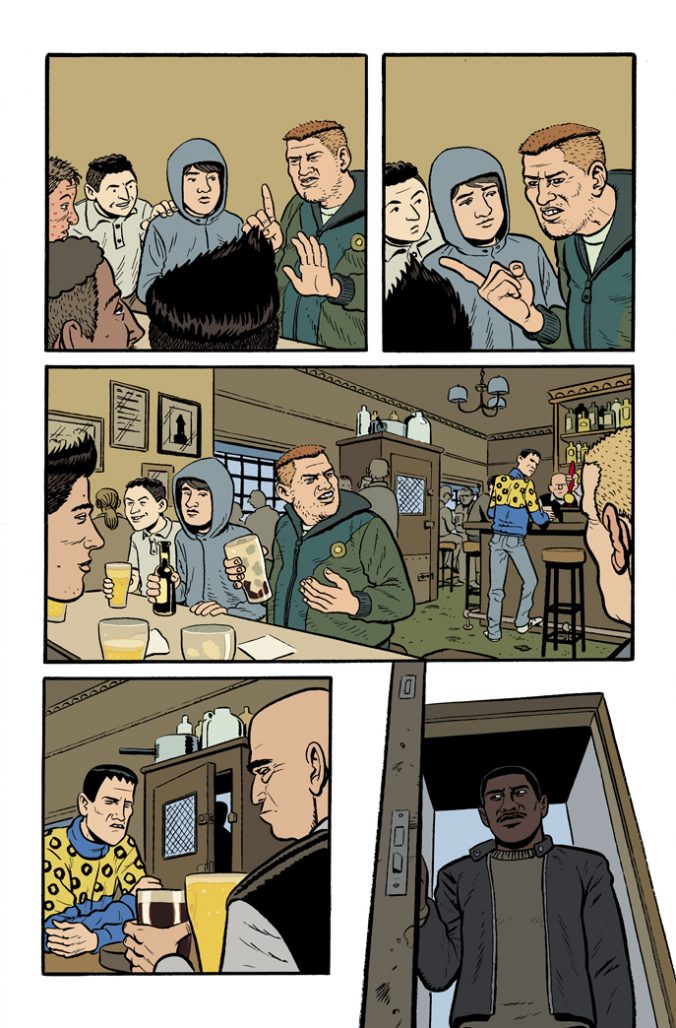

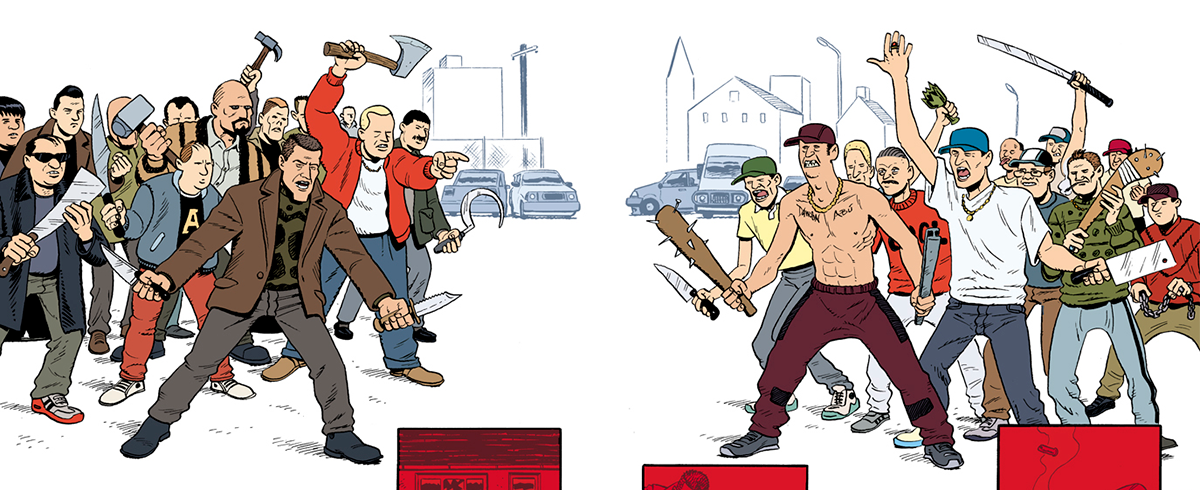

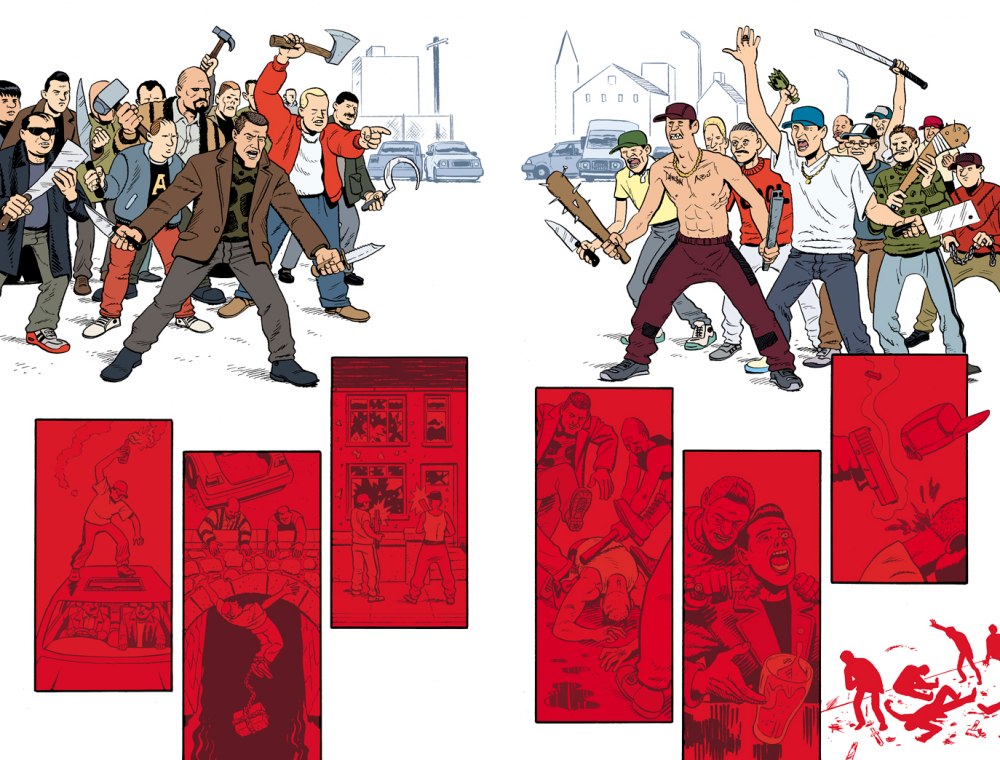

So, Savage Town is telling the story of these crime gangs that are being built up at the same time that Ireland as a whole was being built up as this economic powerhouse. Back then, there was a massive gangland problem in Limerick. It was basically two feuding families and it was bedlam there for the bulk of 10 years.

I was at art college in Limerick at the time, so I knew a lot of the stuff that was happening. It would kind of end up on the news. I remembered a guy named Eddie Ryan was murdered in a shooting in a pub just across the road from where a couple of my friends lived. It was happening around us, but we didn’t understand what it was, you know?

Limerick has a very bad reputation for gangland violence, but it’s deserved and undeserved. All that stuff happened, but it was also very sensationalized in the Irish media, which kind of makes it a little bit sensitive for this book to come out in Ireland. I’ve had a couple of problems with some people from Limerick thinking the book is a different thing than it is.

Originally, I was thinking of doing a straight true crime story in Limerick, but once I got more into it I wasn’t comfortable with the level of responsibility I would have towards people who actually were victims of crime. Also, I didn’t want to glorify what those guys did because they did some pretty horrible stuff. I felt the best way to do it was to create my own characters in that real world. Therefore, I could make them as likable or unlikable as I wanted to.

Lu: What did some of the people that have problems with the book think that it was?

Shalvey: Ah, fuck it, I’ll just say it. I was invited to be part of this creative festival in Limerick to do stuff around the book when the book comes out. I was like, “Nice one, that’s great, I’d love it.” I want to go to Limerick and really kick up a stink about the book. I’d be delighted to do it. But, I sent them the first 20 pages and I was pretty much uninvited. I was raging about it at the time, but ah fuck it what are you going to do? They told me that Savage Town was too close to the bone for some people out there. But I’ve shown it to some people from those poor areas and they think it’s brilliant.

I think because Limerick had a massive stigma, there might be a slight problem with the more middle-classy people who want to get away from [the shitty parts]. They don’t want to go back to that, which I can appreciate, but…it happened. Pretending it didn’t happen isn’t going to help nobody.

Lu: I didn’t realize that this book had the potential to strike such a sensitive nerve with people.

Shalvey: We’ll see what happens when the book comes out. I was on a Limerick radio station and they took issue with me calling it Savage Town. They’re like, “Well, isn’t that very negative?” But here in Ireland, “savage” means great. “Did you see Star Wars?” “Ah, yeah it was savage!” And that pissed me off because they know full well what “savage” means. It also means something terrible, but that’s what I play within the book. A lot of words mean two things.

I could’ve called the book “Stab City,” which is what Limerick was called at the time. Limerick hates that, but it would’ve been a much cooler title, you know what I mean? I think that would’ve done much, much better in a Diamond catalog if it was just called “Stab City” because it really rolls off the tongue. But I don’t want it to be glorifying what happened at the time. If anything, I’m trying to humanize what was happening at the time.

Lu: You said you didn’t totally understand what was happening in Limerick while you were living there. How did you interpret the events at the time?

Shalvey: At the time, I was like, “Ah, fucking scumbags.” To be honest. They shot people. Your feeling is “fuck ’em. They’re all killing each other, who gives a shit?” The problem was they weren’t just killing each other though, right? They were killing a lot of people who were innocent bystanders. Somebody was supposed to do a hit on somebody and it would end up just being somebody who looked like the guy [they were targeting]. They were fucking idiots anyway so, they weren’t getting stuff right half the time. Also, there were a lot of kids just high on drugs and having weapons…they thought they were brilliant. Basically what you would do is you would dismiss them all as scumbags.

To just demonize them as scumbags…don’t get me wrong…I run into people and I do not like them and I certainly ain’t thinking that they’re great, but as more of a softy liberal type, I do feel that there’s an element of responsibility that we just don’t do. I wanted to humanize these characters. I certainly didn’t want to, like I said, I didn’t want to make them seem like they were cool or they were great or they were heroes, but I certainly did want you to like them because I feel if you like them you have a harder time dismissing them for what they do.

Lu: This is absolutely exactly something that America does as well. It’s something that The Wire—something I think you’ve compared Savage Town to in a few interviews– tries to do throughout, it tries to humanize these people, but it doesn’t excuse them for what they do.

Shalvey: Yeah, well, COMPARE is a strong word! Maybe inspired by! I wouldn’t want to lay claim to Savage Town being anything as good as The Wire but the show was definitely a massive inspiration. From a thematic point of view and to a degree, a structural point of view, the show was important. I’d say Savage Town is a very lowbrow version of The Wire.

The Wire had a massive effect on me I have to say. I mean, we don’t have black gangs and such here, but I absolutely have dismissed people as scumbags, and I can see the parallels. Again, I guess Savage Town is…a very diluted Irish version of The Wire in that there’s a lot of similar themes. It’s interesting to look at Ireland through that lens, like, Limerick is Baltimore to me. It’s not the capital, it’s not the tourist capital that other cities are, it’s not Washington, or New York, or L.A.. It’s a kind of a forgotten city in the way that Baltimore is. That was kind of where I had the original of, “What if Limerick was Baltimore?” And it came from that. I’m not claiming that it’s anywhere near as good as The Wire.

Lu: You don’t have to claim it right? It’s just nice to be able to be mentioned in the same breath as it.

Shalvey: It’s not for me to say, you brought it up, so.

Lu: It’s my words, they’re not yours.

Shalvey: Exactly, exactly. I’ll stick that on the cover if we have time, “It’s like The Wire in Ireland.”– Lu

Lu: Right, exactly, just so that we have it coming out of my mouth, [Savage Town] is The Wire except it’s in Ireland.

Shalvey: Exactly, yeah that’s it. I’m going to start saying that!

Savage Town is available now.

travellers are stigmatisied because they piss in peoples gardens and leave a fucking dump site that has to be paid to be cleaned up a great expense by people who actually pay taxes.

The park where i lived was left with discarded nappies and food scrapes and over unmentionables. It looked like a rubbish dump an was practically a no go area withe the threats an intimidations just from walking through the camp(which one had to do to get to work)

This happens every couple of months. Every firm in the industrial estate now has to have huge concrete pillers to stop them setting up camp.

And this is comming from personal experience not some bullshit tabloid story.

Behave like animals get treated like animals. Actually that’s not fair animals have better hygiene.

I don’t know whether to fear and loathe travellers as I am not aware of this and the fact that I’ve never been to Ireland so I can’ , but guessing from the interview and the story the whole point is to look deeply at the cause of why certain people are hated or why they do terrible things, that people we call scumbags may be more human than we are lead to believe. Similar situation can be said for the movie Train Spotting , like Ireland Scotland has issues with the English and that the protagonists are drug affects who are also hated and stigmatized but doesn’t mean they are scumbags 100 percent.

Comments are closed.