Starting in 2011 and ending earlier this year, the book is about Chatterjee’s work which involves military contractors, drone warfare and surveillance. Readers will recognize many of the people that Chatterjee meets including Julian Assange, Edward Snowden, Laura Poitras and others. The book manages to get at the heart of these issues in a very thoughtful way. It is also more unsettling because with perspective, Chatterjee and Khalil are able to explain what is happening and place these events in a larger context. How Snowden’s revelations about spying are not just about the privacy of Americans but key to how the drone project operates, about just how ineffective drones are, and the heroism of ordinary people, including many young soldiers, who have spoken out for what is right and to inform the public of the truth. Verax is an important part of a conversation that all Americans need to be having.

Alex Dueben: Pratap, you’ve been working as a journalist for many years. When did you first become interested in questions around surveillance and drones?

Pratap Chatterjee: I’ve been writing about the war on terror pretty much since it began – maybe even before it began, in some ways. Not necessarily about surveillance but I’ve writing about military contractors since the late nineties. Before the war on terror you mining companies and oil companies and these big extraction companies in places like New Guinea or Peru, who would hire security companies to help protect their operations form angry locals. That’s where I started looking at military contractors. This really kicked into high gear post-9/11 when the US decided to invade Afghanistan. It became very obvious to me that they were going to use contractors in a big way. They started to expand and by the Iraq war, they were the principal way the US conducted war in the Middle East and Central Asia. As the Bush administration wound down to close it also became fairly obvious to anybody tracking this that they were moving from on the ground operations to remote operations using drones. I followed that and became interested in who it was that was providing these services. I went to Pakistan to meet victims in 2011, which is recounted in the book. So it wasn’t a new subject for me, it was certainly something I’d been covering for a while however to find out who contracts for the CIA is a whole other ball of wax. The State Department and Department of Defense and USAID issue press releases saying, we’ve hired so and so. When it comes to the drone war, this happens behind closed doors.

Dueben: You talk about this very briefly in the book, but what made you interested in making a graphic novel?

Chatterjee: It’s really Khalil. I’d never written a graphic novel before and obviously as a kid I read comics, but it’s really Khalil who pulled me into this. Khalil and I have been working together for years. I would write an article or my writers would write an article and he would make a cartoon. We’ve been doing that for about ten years. I was away in England and when I returned he said, what do you think of working together on a graphic novel?

Khalil: I was born during the war for independence in Algeria and I was always very political, and very concerned with the general political climate around me – whether in Algeria when I was a kid or I came here at age 20 – because I always understood how it affects me. How a war can get me killed. How a lack of democracy can get me in trouble. I was always passionate about these things. As a political cartoonist my slant has always been for the underdog. Being interested in the people who don’t have much power has been a theme throughout my work as a political cartoonist and as a graphic novelist. Resistance to political oppression. I was always interested in the whistleblowers whether it be Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning. I briefly thought about doing a graphic novel about Manning. Pratap and I, as he was saying, have been working together for a number of years and I knew this was his beat. I knew he was very close to it and I thought maybe Pratap would agree to do this with me.

Dueben: How did you decide to approach these issues in the book, because ultimately it follows you Pratap as you’re trying to understand what is happening and how this system works.

Khalil: In the beginning we were more focused on the whistleblowers and at some point we came to realize that the drone warfare story was very important. At first Pratap was a little reluctant to be in the story so much and I persuaded him to not be so modest and camera-shy. The editor also encouraged us in that direction so Pratap ended up being a large part of the protagonist who we see throughout the book.

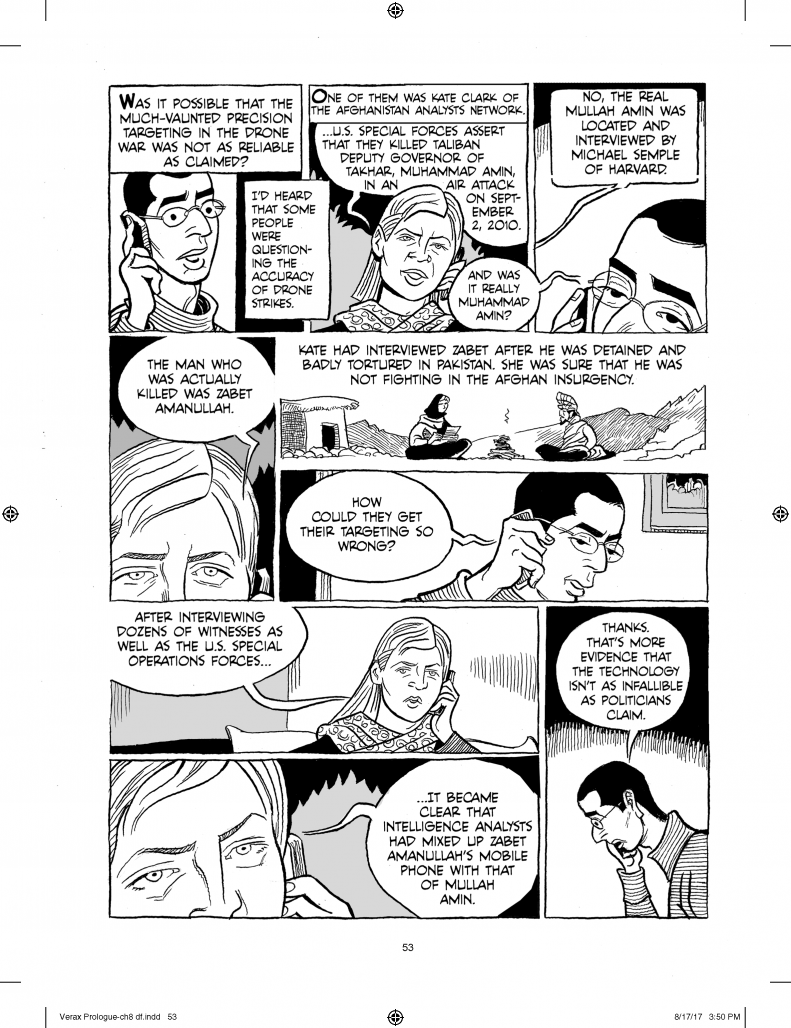

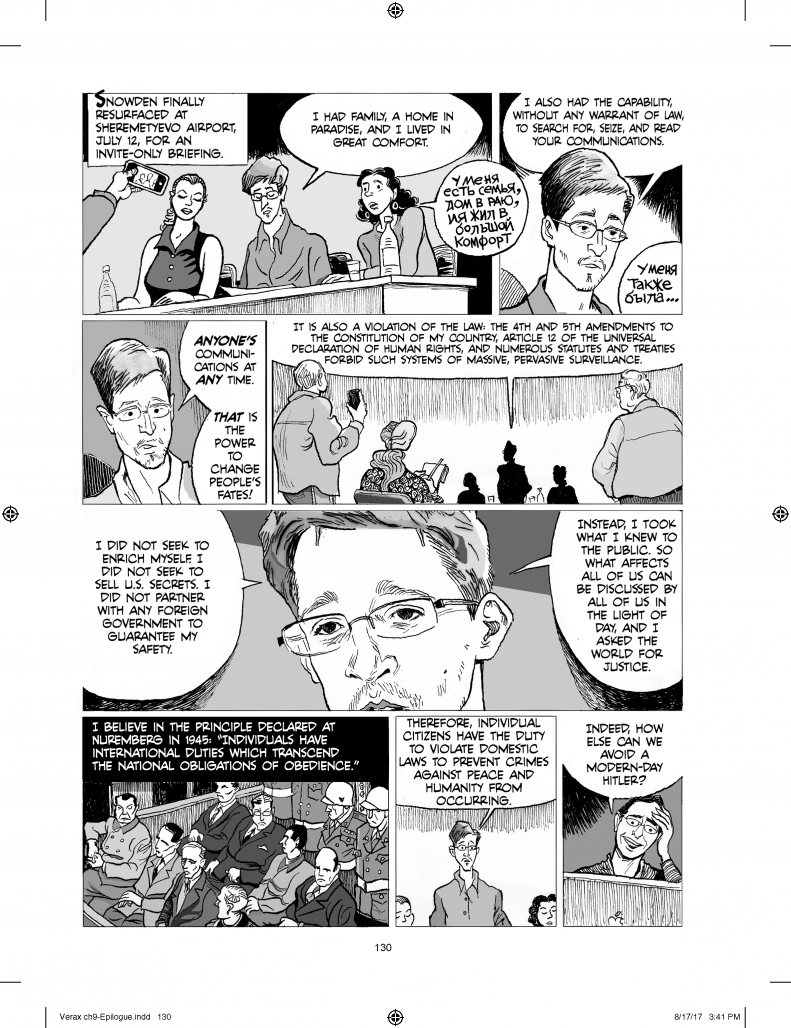

Chatterjee: Initially the idea was that this book was going to explain surveillance and tell Edward Snowden’s story. It was not about drones. I said it’s about Edward Snowden and he should be the central character, but Edward Snowden came out so to speak in 2013 and the book starts in 2011 but concludes just a few months ago so the book evolved as we went along. Half of the book occurs after we started writing it, so it evolved as it happened. Khalil and I would sit down once a week and I would say, guess what happened today? It became looking at these issues through my eyes and therefore became about my work. You can’t really separate surveillance and drones and that’s something we try to convey. The US military and the CIA don’t surveil people to snatch their information and blackmail them – although that is the kind of thing they do. There is a bigger reason which is that they’re trying to track people and target them and potentially kill them. When you tell Edward Snowden’s story, most people think it’s just about spying on Americans, but there’s a bigger story and I really wanted to tell that story. We started telling the story of Snowden and then we stepped back in time to 2011 when I went to Pakistan. It was going to look at other whistleblowers and then it became a key element of a much bigger story on the war on terror.

Dueben: I think that’s an important point because in the U.S. most people think that we are either the hero of the story or the victim – or we tend not to care about the story. People see Snowden’s revelations as about our privacy, when in fact what he exposed was this much bigger story about how the U.S. is waging war right now and a lot of coverage and conversation seems to miss this global context.

Chatterjee: And the impact of it in terms of blowback – which we don’t talk about much. My previous book Halliburton’s Army is about Halliburton being the key contractor in the war on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan, but they’re a logistics company. They’re building bases and that sort of thing. It’s a dense journalistic book and at the end I was really surprised when I got a good review form the military. The military said this is actually true. I wouldn’t be surprised if people in the intelligence community would say, this [book] is true. They would agree that this is why they track people. This is not intended to be a defense of why they track people – but I think they would say, we’re not snooping on you because we want to be able to blackmail everybody, we think we can find terrorists this way. I think it’s deeply problematic, but this is why they do it. It’s not even necessarily a secret, but we as US citizens – I’m not actually a US citizen, but still – just assume it’s all about us. We take Snowden seriously because we think we’re being targeted, exactly as you said, and we should see this in context.

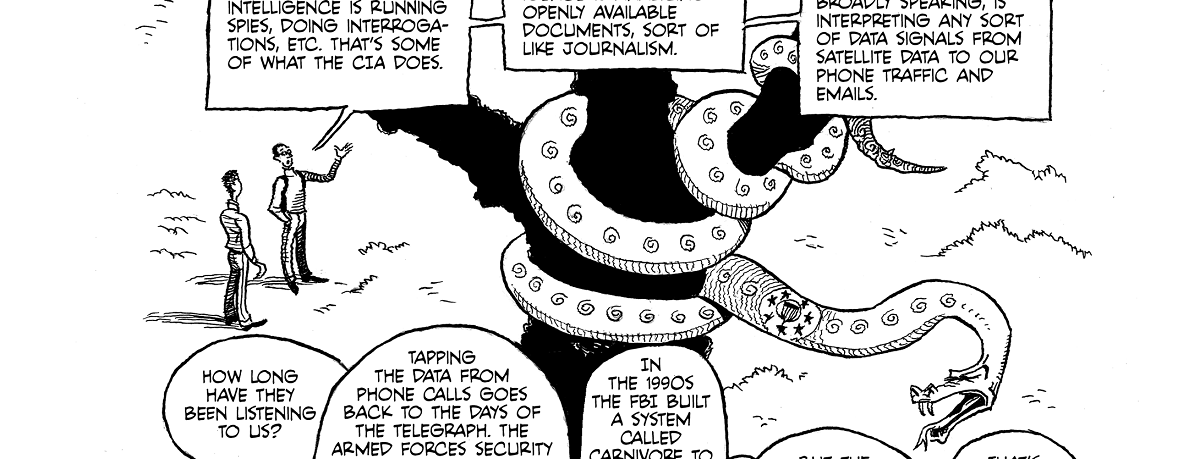

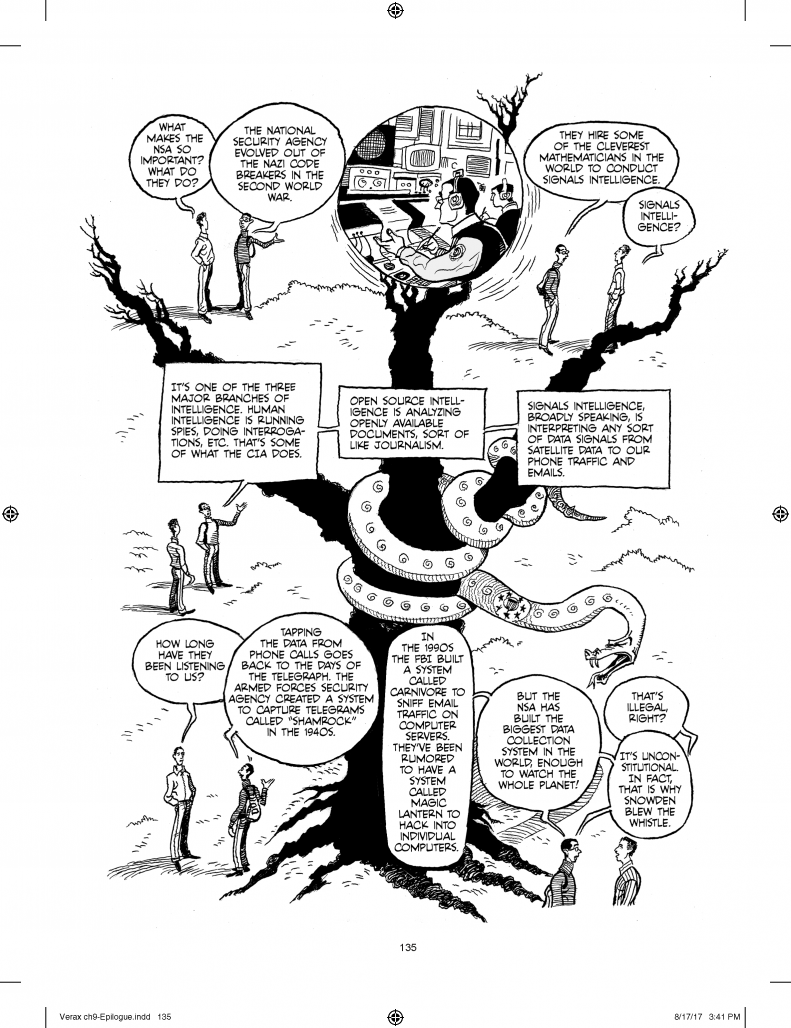

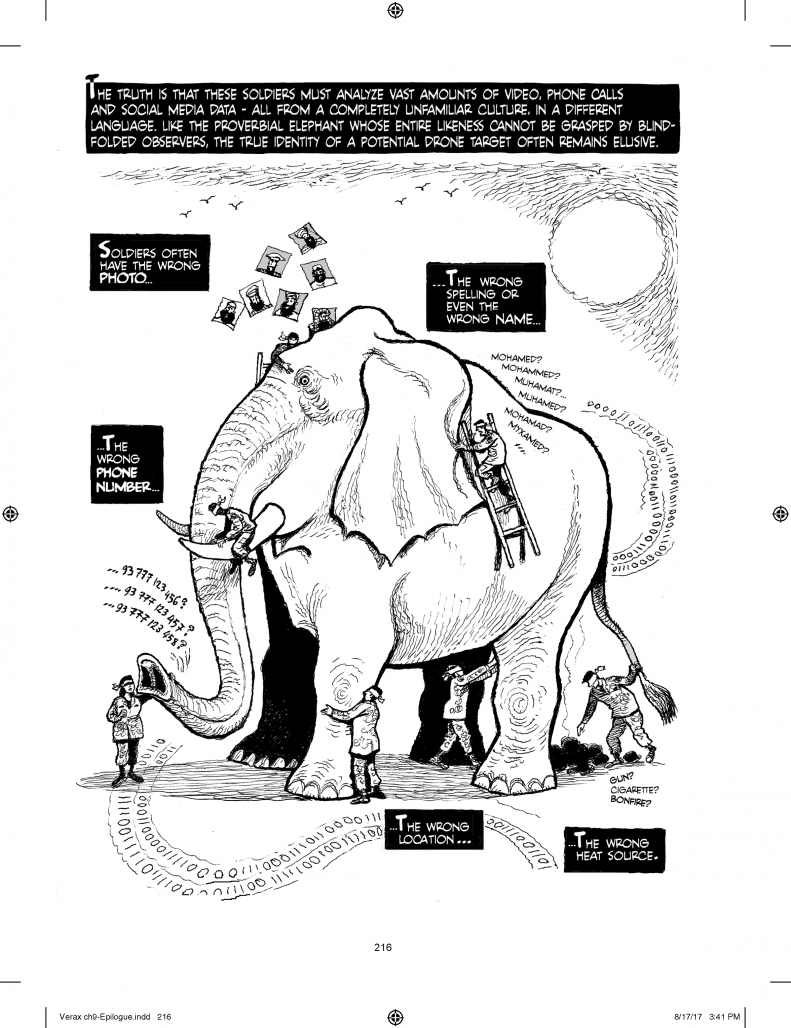

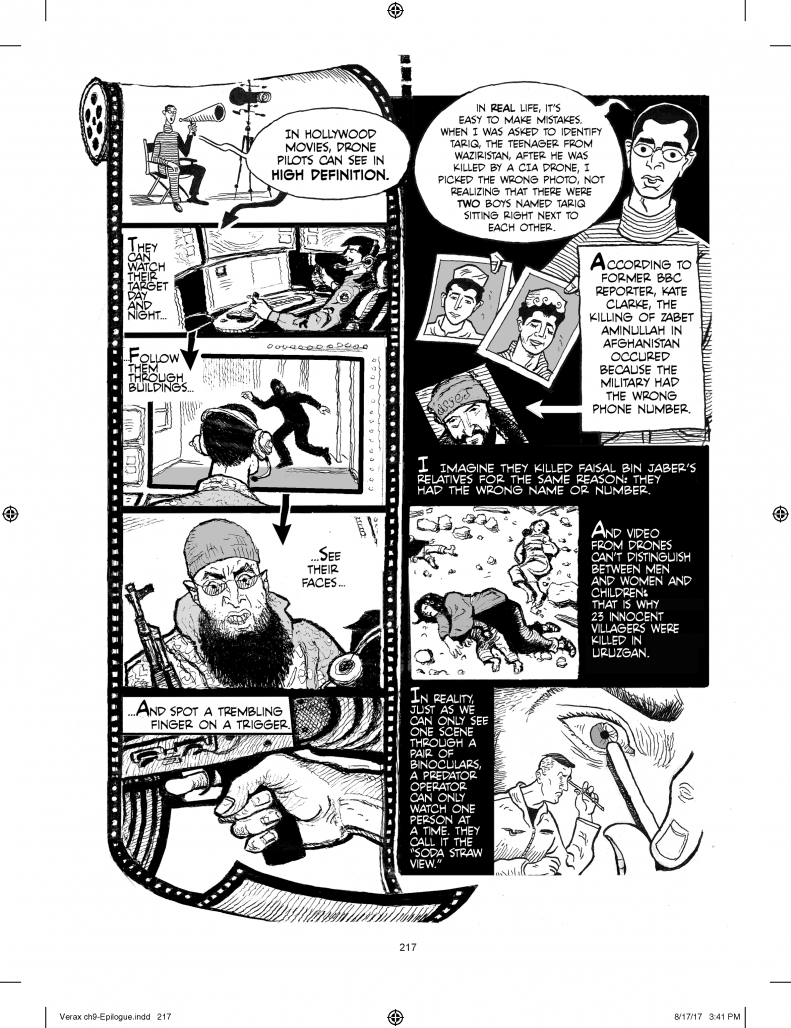

The context is hard to convey to people and I still struggle with it. In tracking people there is a danger because so many mistakes can be made that you kill the “wrong person” – if there’s a right person to kill. It’s really dangerous to scrape up data about people and then imagine that you can project who’s a terrorist and who’s not. It’s not a system of justice – it’s just data. That can give you evidence, but it’s not a system of justice. The military says, we know where you went and therefore we can decide whether or not you’re guilty and then choose whether or not to kill you. In reality I think anybody who was fair minded would say it’s not possible to make these judgements solely based on data. I could leave my phone at home or I could have lent my phone to somebody else and so the idea that just by tracking your movements based on where your phone is, is really flawed. That’s the kind of information this war is predicated on. We’re trying to explain how we can all be targets because of this deep reliance on data and technology. Data has taken over and replaced everything else.

Khalil: It’s a question that Snowden rightly pointed out is about the rule of law. Do we have a Constitution or do we not? If we do, then how do we justify killing foreigners in foreign countries? How do we justify that and bypass the law? I think Edward Snowden and the whistleblowers are heroes. They’re very courageous and they are focused on a right to privacy. U.S. citizens are affected by this. We wanted to show that it goes beyond just the U.S. focus. A lot of people outside the U.S. are paying for this so-called war on terror that are completely innocent, that are being shot through no fault of their own. Pratap and I wanted to show the link between the two problems. The problems we have in this country with our privacy being disregarded and even worse outside [the U.S.] in places like Pakistan, Afghanistan, Yemen, where people by the dozens can be killed on the suspicion that there may be a terrorist in their midst.

Chatterjee: You can’t say here, I’m pretty sure this person is guilty and therefore we should execute them, but that’s the standard the U.S. military uses under Obama and now under Trump. We have some data on them so we think this person is guilty. Even if they had access to all our data – and even if it was accurate data – even if you were to agree that it’s okay that if you have a warrant their privacy should be invaded, that doesn’t supplant the system of justice and a right to a fair trial. It’s become an easy way to solve a political problem. Terrorism has not disappeared because of the drone war. In fact the situation has gotten worse. It makes it possible for a politician to say, I’m doing something about it; I killed a terrorist. Now and then they kill someone they have named but there are more than 6000 people they’ve killed. We don’t have their names, we don’t have any evidence, they weren’t allowed to defend themselves. It’s based purely on some very poor data that was interpreted by a group of soldiers working in disparate locations. This is a really problematic way to conduct a system or accountability or justice – if that’s what it’s supposed to be. Maybe that’s not what it’s supposed to be.

Dueben: You also get at something important in the book, which I think a lot of us were not paying attention to, the degree to which this has been outsourced to private companies who know have these weapons and all our information and data.

Chatterjee: This was the natural evolution of the writing I did before on companies like Halliburton and Blackwater. A bunch of these soldiers straight out of high school – some of them are named in the book – are put in front of a computer and are told, we’re tracking terrorists so when you see this individual you can request permission to fire. There are two kinds of soldiers involved in this. The pilots are officers which means they have a graduate degree, they went to the Air Force Academy, and then the enlisted soldiers came straight out of high school, who have done boot camp and basic training and maybe an intelligence course and after eleven months they are then put in charge of people’s lives. Of course they don’t speak the language, don’t understand the culture or know these locations, but the computers are programmed to track phone numbers. They’re told, this person in your crosshairs is likely to be a terrorist so if you see them doing anything suspicious let us know and we can kill them. The soldiers don’t have a name or context. You can say, we programmed the phone numbers of these dozen terrorists, our soldiers found them, and then they killed them. Nobody questions whether the computer got it right. Or whether or not they have a reasonable explanation as to why they were at a certain place at a certain time. In Yemen for example, I think there’s one gun for every person. Same thing in Waziristan. Everyone has guns. It’s almost like being in America, in fact even more. Having a gun doesn’t make you guilty.

You can make a distinction between two different kinds of drone surveillance. One is what’s called Overwatch. If you have American soldiers in Afghanistan, the drones watch over them to make sure they don’t come to any harm. They can see around the corners. That, to my mind, is not an unreasonable use of surveillance. To protect people who might be on a dangerous mission or on a diplomatic mission. You’re following somebody who you know is doing a certain thing, namely a US solider or US diplomat. On the other hand if you’re going to turn the system around and say therefore I know who is a terrorist and I can kill them, you have a problem. Those are not the same thing. Overwatch and Tracking unknown people is a whole different thing but they’ve been conflated.

Dueben: Khalil, so much of this book is about e-mails, it’s conversations, but you make it a very visual book.

Khalil: Thank you. It wasn’t easy. [laughs] For many years now I’ve been a political cartoonist and what that consists of is turning usually fairly complex issues into very simple, immediate images. I trained myself to do that it’s not something that’s new. Having said that, the level of complexity and the esoteric nature of some of the material here was a challenge. It wasn’t just a matter of summing things up as I usually do, it was a matter of actually conveying some of the detail – and there’s a lot of detail. That was the hard part. Not to get lost in the minute, intricate details and make things digestible. It was difficult. Very often I would just scratch my head. It’s mathematics, it’s physics, how do I turn it into something people can actually read and not get lost in? I hope I managed to do it. I was constantly trying to find the image or the sequence that would make this palatable to the average reader – let alone to the young reader because as Pratap was saying earlier, one of our goals was to make this accessible to people who are not necessarily wonks. The hardest part was that we were doing this book in real time. Things would change by the day and I would have to go back often. [laughs] That was difficult. My previous graphic novel Zahra’s Paradise was not as complex in terms of the data and it was also done sort of in real time. For that one we serialized it on the web so I was getting feedback as I was drawing. This was harder because it was more complex and we were not getting feedback because we were not serializing it so we often had to take a deep breath and hope it was working.

Chatterjee: It’s now been almost four years. We met probably weekly over that process and went back and forth. The ironic thing is I have a degree in art, he has a degree in geology and languages. [laughs]

Dueben: The book ends earlier this year, so I’m guessing that you guys were writing and drawing it until the day you sent it to the printer.

Khalil: Pretty much, yeah.

Dueben: This is an unfinished story, as you acknowledge in the book. What was the challenge in finding an ending for the book?

Chatterjee: The election of Trump, which I think very few people anticipated, just threw us for a loop. There’s no way of knowing what happens next. He’s so unpredictable; he could ground all the jets and use only drones. I mean, who knows? In some ways this is an opportunity to show how problematic this system is in the hands of a man as unpredictable and mercurial and ignorant as Trump. We don’t want to say that is just dangerous in the hands of Trump. Obama did a lot of damage and under his presidency this system really evolved and expanded. It’s funny, writing Halliburton’s Army people said, oh the book is about how Dick Cheney devised this system to enrich his buddies. No actually, it’s about a system of military logistics that’s evolved over decades. The same thing with drones. The reality is that the military machine has evolved over many presidencies, many political parties, and it’s not going to stop tomorrow. The book was actually supposed to come out last fall, and of course like any good book it took longer than we anticipated. [laughs] But we felt like we needed to have the context of the current political situation. We hope this book is a call to action. The way to resist is to blow the whistle, to support whistleblowers, to tell the truth. It was true a year ago, two years ago, and it’s even more true today. It’s the only way we can fight for justice.

Over the years I’ve been to Iraq, I’ve been to Afghanistan, I’ve been to Pakistan, I’ve lived in Jordan. I think a lot of people of the left tend to focus on the victims in those countries and I feel it’s really important to understand that it isn’t just people there that are affected; it is also people here, notably soldiers. If you want to challenge the National Security State, you can only do that with the support of people in the military and with the soldiers themselves. If we’re going to do something about this we need a movement that goes beyond the left, that goes beyond the general public, it involves the soldiers themselves, it involves the victims and the victims families. I hope one thing that this book conveys is that this is about the role of people in government and people in the military who can speak out when they see wrongdoing.

Khalil: It’s about resistance and resistance is not the monopoly of people outside the system. That’s the beautiful thing and the beautiful part of the story, you have people within the system who have a conscience who are resisting. Snowden and all of the whistleblowers we featured are very courageous. They decided one day that they can’t take it anymore even if their lives are going to be wrecked, they decide to do the right thing.

Chatterjee: We live in Berkeley and I gave a lecture at the engineering school about these technologies and the problems with them and I had ex-military people come up to me after and say we think this is true and it’s important to talk about it because we can’t speak out about it. I hope that this is a book that conveys the experience of those soldiers that are fighting for justice and against the political powers that use this system for their ends – both Obama and Trump.

Khalil: You know the old joke that so-and-so was country before country was cool? We were resisting before resisting became cool. This isn’t about Trump. It’s about the whole system leading up to the situation where we now have a Trump in the most powerful office.