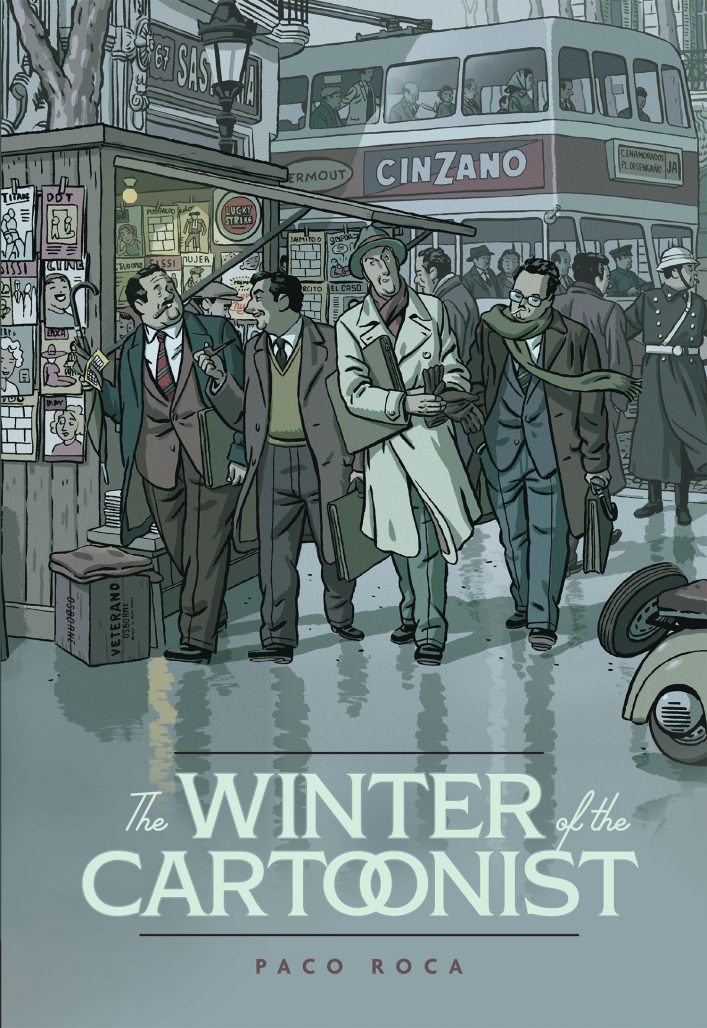

Multi-award-winning Spanish cartoonist Paco Roca is no stranger to creating historically grounded tales. In graphic novels like Twists of Fate, The Lighthouse, and The House, he draws from societal or personal past events, weaving the details into seamless human dramas.

The Winter of the Cartoonist is a graphic nonfiction tale of five courageous artists in the 1950s who left one of Spain’s largest publishing houses to take creative control of their work and start their own magazine. Roca offers a probing look into the lives and struggles of cartoonists in the wake of the Spanish Civil War.

The story is also a very personal one for Roca, featuring his childhood heroes. In this interview with The Beat, he generously shared thoughts on the complexity of writing about still-living people, his research and discovery process, insights into his narrative choices, and more.

Heads up: The interview does contain a few “spoilers” on the story (can you be spoiled on historical events?), so revisit this article after reading The Winter of the Cartoonist if that’s a factor for you.

This written interview was conducted in Spanish and translated by The Beat‘s own Ricardo Serrano Denis.

Kerry Vineberg: What was the process like to research the history for The Winter of the Cartoonist? Do you have a favorite story of uncovering some part of it?

Paco Roca: With this comic I wanted to fulfill my dream of getting to know my heroes a bit better. I’ve been reading comics since I was little and like most kids, I read the ones that were put out by Editorial Bruguera [the publishing house in the book].

They mixed in stories from different time periods. You could read stories from the 1970s followed by a few that came from the 1950s. I wanted to be an illustrator just like those featured in the magazines, but I also wanted to know the people behind the comics. I wanted to know what their drawing process was like, how the editorial worked. None of those details appeared in the magazines and the illustrators were kept pretty anonymous.

So, decades later, working on The Winter of the Cartoonist, I got to research those artists and their lives.

I was pretty disappointed when I learned most of them worked alone in their homes, sometimes at their kitchen tables. It wasn’t as glamorous as some tend to think it was. They were exploited by their editors and many ended their careers in near financial ruin.

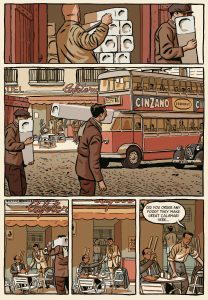

What I found myself truly enjoying was going to the places these cartoonists frequented. I drank coffee in the places they drank coffee and bought my inks and pencils from the store they bought them from, which is still open to this day.

Vineberg: How much of the details were research versus creative interpretation? Were there any mysteries you had to fill in the blanks on with invention?

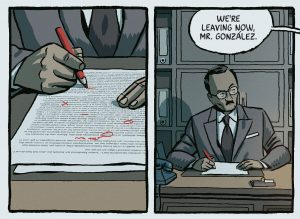

The emotional arcs and character motivations had to be filtered through that process too. Curiously enough, I received a letter from one of the lawyers at the editorial, Ledesma, and he said that I captured everything just as it was. The same happened with the daughter of one of the main characters. She reached out to say that she now understood why her father, Escobar, didn’t want to discuss that part of his life.

I really don’t know if I actually managed to stay within the facts such as they expressed them or if I created a new fiction that they now want to believe is true.

Vineberg: You often bring a historical background into your books, but this one seemed to feature a journalistic effort. How do you approach the creation process differently from your purely fiction books?

Roca: I’m fascinated by history. Making comics is my way of understanding, reflecting upon, and contributing to the grander narrative. I don’t see myself as a journalist or a historian in the sense that I’m contributing new information no one’s provided before. I’m just glad to add a certain degree of life to the historical events I’m interested in.

I think that’s my objective and it is the same for fiction in general. In that sense, with The Winter of the Cartoonist and my other comics, I try to keep things on an even keel. I want to respect the real-life events just as much as I want the story to resonate, so there’s a healthy amount of drama and so its characters seem alive.

Vineberg: The way time moves in this book is interesting. How did you settle on framing the story non-sequentially?

I also decided that narration would not adhere to chronological considerations, so as each character remembers the events that took place, it all becomes a kind of multiple-reality puzzle the reader has to put together. Novels like Leaf Storm by García Márquez or movies like Rashomon by Kurosawa use this structure and I wanted to experiment with it as well. I will admit that it gave me more than a few headaches making sure the facts coincided with that structure.

Vineberg: There are many characters in this story. Who were your favorites and why? Did you see any as the main character?

Roca: There are two characters that are special to me. One of them is Escobar. He’s kind of like the dedicated hero figure, a fighter and optimist. Escobar wasn’t just an excellent illustrator, he was a playwright and an inventor of all types of artifacts.

Vineberg: Could you elaborate on what this history means to you as a modern Spanish cartoonist and a fan of these cartoonists growing up?

Roca: Looking back in time helps us better comprehend our place in history. Knowing the life and works of those cartoonists has helped me understand my place in that long line of cartoonists that have contributed to the form. You find that you worry over the same things, that you use the same language they do. Looking at their work, you understand how the comic book world has evolved. And not just in terms of authors’ rights.

Those artists couldn’t imagine that comic book storytelling could be used to tell other types of stories that weren’t just comedic or juvenile adventure stories. It makes you wonder how future cartoonists will see our work forty years from now.

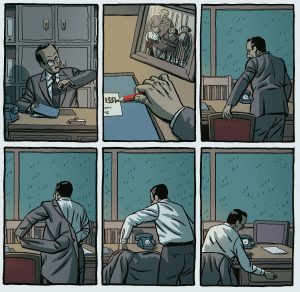

Vineberg: Several of your books have a quiet, detail-oriented element to them, like Wrinkles and The House. The Winter of the Cartoonist is also quiet in that the rebellious actions are more conceptual than physically demonstrative. Are you drawn to telling that type of story, and what techniques do you use to make it interesting visually?

I think it’s necessary to include those smaller details organically as you build the story. And without a doubt, silence helps flesh out the emotional spectrum of the story. That’s where you give the reader time to think and add their own emotions to the narrative.

Vineberg: Any big challenges or surprises while putting together this tale?

Roca: In a way, yes. Working on a story that contains characters that are either still alive or have families that are aware of the project does bring with it some complications. I couldn’t stop thinking about how they would react to it. I think it made me rethink certain aspects of the narrative.

Vineberg: Anything you can share about your next projects?

Roca: I just published Regreso al Edén (Return to Eden) in Spain. It’s a story about a photograph that my mother holds dear. It’s the only picture she has of her and her mother together. Her mom died when she was very young, in postwar Spain, a time of much misery. That picture has always been very close to her. Wanting to know more about what’s behind that photograph and what it means to her is what made me want to work on this story.

Published by Fantagraphics, The Winter of the Cartoonist is on sale now.