Edie Nugent: You worked on video games before you started writing comics. How did you get into that, and what kind of work did you do?

Monty Nero: I designed characters, mostly. It’s a frustrating job though, because there are so many people involved, so much homogenization, that you never feel much ownership. So the great thing about comics is it’s just you, the artist and a bit of paper. There’s only one conversation, the one between writer and artist. Your ideas reach an audience pure and unadulterated.

Nugent: Did that frustration over creative control help give you the confidence to write and pitch Death Sentence? Because the route you took in standing behind the book and initially self-publishing it, it’s a tough path.

Nero: Yeah, I guess. Not so much confidence as desperation, though. You’ve got all the ideas and they keep getting snuffed out. You see years ticking by. You think ‘is this it? Is this all I’m about?” And eventually you’re so frustrated off you just say ‘fuck it’ – and go for it…

Death Sentence could’ve bankrupted me. My great hope and desire was to break even, to be able to make a pure statement without losing money. The fact that it made money, and we can make more, was unexpected. Though I’m not very interested in the money side. It’s being able to make more, to explore our world through the comic; that excites me.

Nugent: Did the personal risks you were taking in creating and publishing the book inform your writing process? Because there’s a real sense of urgency there, not just in the “6 months to live premise”, but also in the way Verity, Monty and Weasel express themselves.

Nero: Yeah, totally. It’s the way to approach any artistic process I think. Analyze the world around you. Analyze your own predicament, your feelings and perceptions. Then channel it into the work. Into characters and artwork.

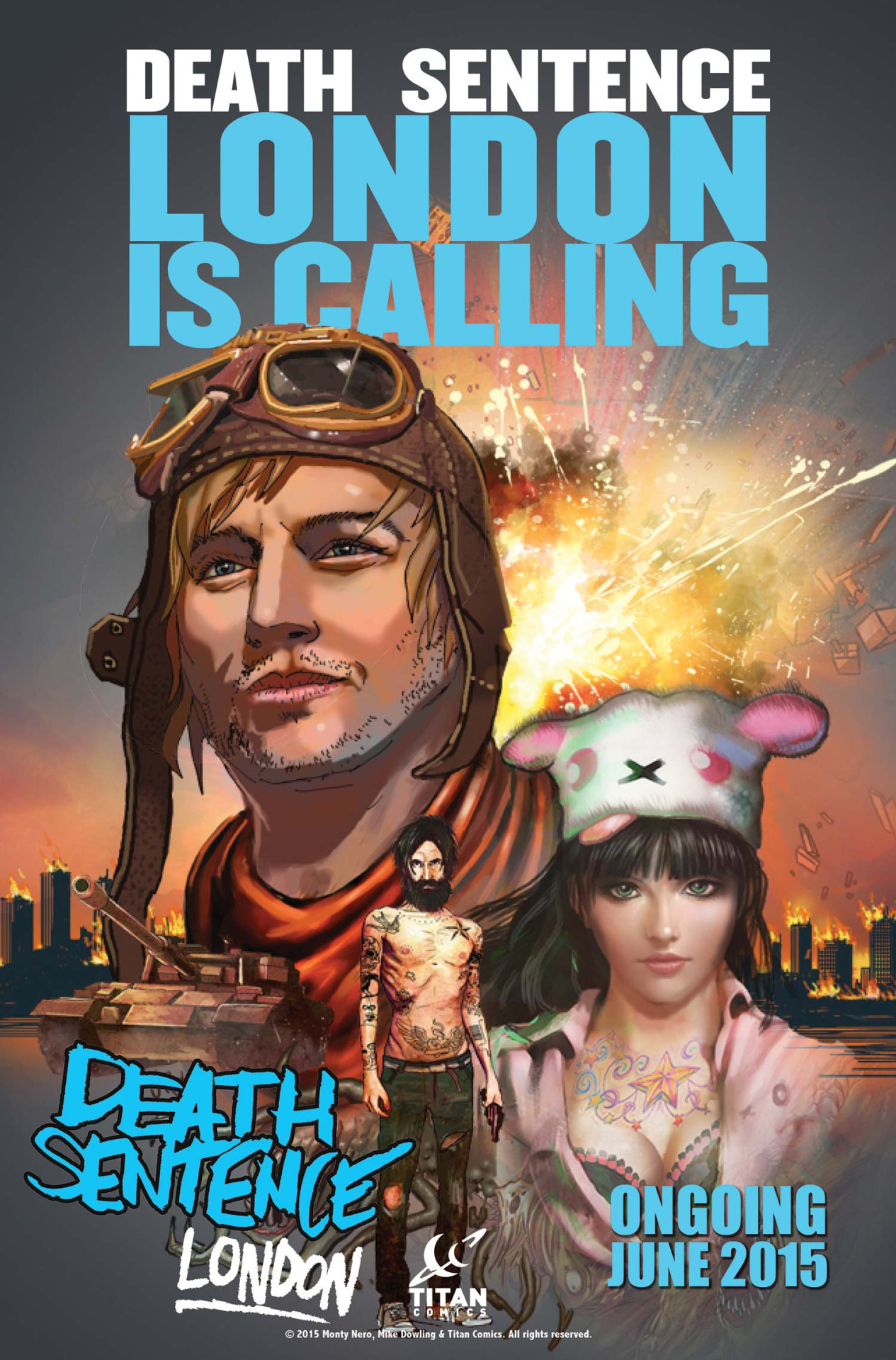

Nugent: So Death Sentence: London issue 1 is out in June. What was it like returning to series and writing for your characters again after working on major label titles for Marvel and Vertigo?

Nero: Well I never stopped. I took those gigs because they didn’t interfere with what I was doing, which was making more Death Sentence. So I’m about three years ahead. It’s been very satisfying scripting long term and plotting things out. The problem is there are so many stories to tell, so many great characters and situations, that while you’re writing one you feel you’ve neglected another.

There’s a fantastic Weasel story coming up, for instance, but he’s busy doing other stuff for the next year or two. Cool stuff, but not as cool as his solo story later on. I can’t wait to tell that story, but there’s other things that need to happen to Verity first. There’s been a lot of crazy shit in the news over the last few years, and a lot of it ends up in Verity’s lap.

The Marvel and Vertigo gigs were great fun. I felt honored to be asked. All the editors were real enthusiasts, with a deep love for the medium and a great deal of knowledge to impart. You obviously don’t have the same input you have with creator owned work – but it was a real blast. No downside at all.

Nugent: Have you always been the type of writer who likes plotting out a long-term story arc? Or did the work itself demand that kind of approach?

Nero: No, I guess writing an ongoing comic, which is what Death Sentence is now, is a new thing. Not so much plotting, because writers always have way too much story in their heads – there’s always a trilogy in your mind when you’ve only written a few sentences. But it’s the passage of time over three years of comics that takes some adjustment. It’s slightly weird. You write the script in months, people digest each episode in minutes, but it describes several weeks of story, published over a year.

I mean, what’s the timeframe? It’s surreal. So there’s obviously a lot of flexibility in how you portray time in a comic. The first six issues took place over a few weeks, and if we continue at that pace you’d get about six graphic novels for each character before their time ran out. But you can obviously speed up or slow down, as the story demands. Whatever works best.

Nugent: The story and art of Death Sentence have a real punk rock feel: did any music in particular inspire the work?

Nero: Yeah, I like angry, loud music you can throw yourself around to. I never stand at a gig, I’m always moshing or stagediving or dancing. But like a lot of people these days I’m into the best of everything: rap, punk, rock, blues, folk, classical, whatever. I used a few songs for the chapter titles, which were The Stone Roses, Massive Attack, Lorde, Kate Bush, The Jam, and Blur.

Nugent: There’s a lot of frustrated creativity and a desire to create something that will outlast you at the heart of the Death Sentence characters and story. Is that something you still struggle with even with the critical and commercial success the title has seen over the last few years?

Nero: Good question. That desire and passion remains, but we channel it in other ways. The theme of the second book is the individual against the state. We live in a time of civil protest, whether it’s Ferguson, or Ukraine, or Tottenham, or the Arab spring. But in Death Sentence the protesters and the rioters have G-plus, which changes the balance in terms of how they can express their anger.

That desire to create something that outlasts the individual is still core, but it’s not the main theme of book two and three. This is angrier. And it’s natural those kinds of emotions about legacy would intensify as the characters near death. So we’ll see the theme of creativity coming back to the fore as the story develops. Until then it bubbles under every scene.

Lookout for Death Sentence: London issue 1 in stores June 8.