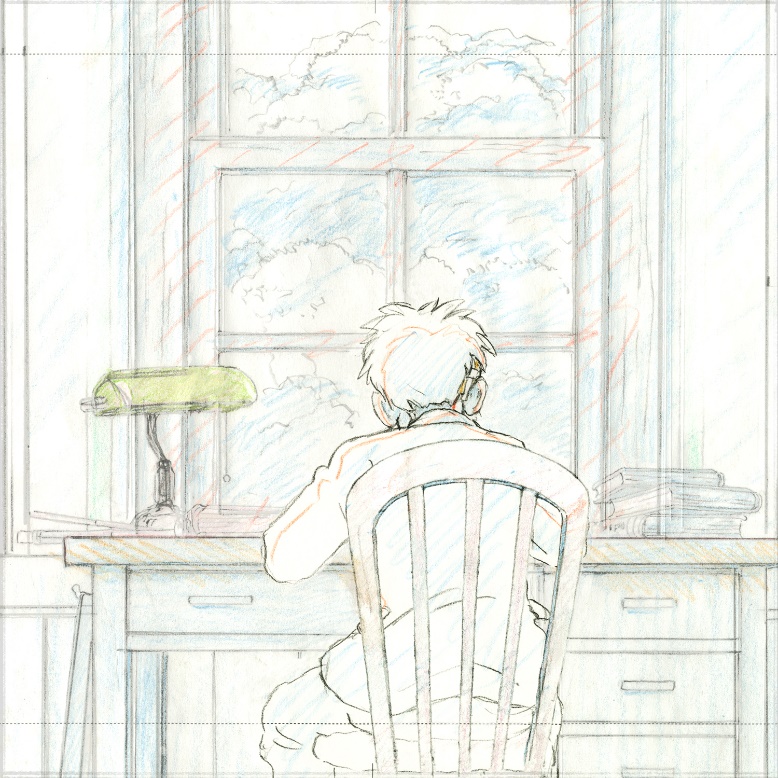

Actor and voice director Michael Sinterniklaas certainly ended his year on quite a high note when the English-language of The Boy and the Heron was released in North American theaters. It’s the newest film from animation legend Hayao Miyazaki, whose name pretty much speaks for itself at this point. Drawing on Miyazaki’s own childhood experiences during World War II, The Boy and the Heron is the story of young boy named Mahito who embarks on a surreal fantasy adventure with the titular Gray Heron as his guide.

Taimur Dar: It’s so easy to watch Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli films in this digital age of streaming. My introduction to Miyazaki was 20 years ago when I rented Spirited Away from Blockbuster on DVD. By the time I finished the movie, I was an immediate fan and couldn’t wait to watch the rest of his work. Luckily, it was around the time Disney was releasing the Ghibli films, so I didn’t have to wait that long. Do you remember the first Studio Ghibli or Hayao Miyazaki film you saw or at least how you were introduced to his work?

Michael Sinterniklaas: The first one I saw was Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. I think it was on HBO. It was mesmerizing and mind-blowing. I was a little bit scared and very intrigued. I had discovered anime before that, but this was this whole new level of it. I saw Spirited Away actually in theaters and was so entranced by the experience of being lost. It was not a normal narrative. You can look at a beginning, middle, and end and it’s quite a hero’s journey. But it feels like getting lost where you don’t know anything. I had friends who were like, “I didn’t get it. It was so confusing.” And I’m like, “Yes! That’s what I loved.” [I felt like] I was a little girl who was lost in a land that I don’t understand. For so many other personal reasons it touched on things in me and I couldn’t get enough of it. I was so moved. And I really appreciated the dub at the time too.

Thanks to the deal GKIDS has made now that they’re representing the library and put most of it on MAX it’s easy. I had to discover anime all sorts of ways. Before I even knew what it was, I caught the occasional show on TV and going, “Why is this so different? What’s with this Battle of the Planets that looks cooler?” I felt like I was getting access to something that was headier and more mature and really satisfying. Then I get to high school and I find two other guys. I’m a man of a certain age so we didn’t have cell phones and the internet wasn’t what it is today. We found this movie rental place that was just off Times Square, in New York, where I went to high school. Go LaGuardia! It was called Tokyo Video and they had Japanese anime from television that was recorded on VHS. We’d go in there and they were like, “Why are you non-Japanese people coming in here?” We’d rent things like City Hunter and it would have commercial breaks and no subtitles. Discovering all this stuff was really tricky. We’d have to rewatch things like Bubblegum Crisis over and over again to understand what the story was about. And then I got to be a part of some of the things I watched. My first anime job was on Bubblegum Crisis actually.

Sinterniklaas: That’s a really intricate answer. I want to interview you about your experience watching the film because it means so many different things to literally everybody I’ve talked to. I’ve seen this movie more than most in America outside of Studio Ghibli or GKIDS. When I first saw it, I realized immediately I had to see it again and try to make some sense out of it. The trick is, and I think this is really crucial to working on a dub of this kind of work for this creator and at this level, I wanted to understand moments, but I didn’t want to change the potential for everyone to experience their own movie. It is the job, but human nature makes this difficult to tell someone else’s truth while you’re interpreting it. While I have opinions about certain things, I was always checking myself to make sure I was not imprinting my value set or my lens on this world. That you would get to experience it in your native language when you watched our dub the way Hayao Miyazaki intended it to be received. That’s a constant tug of balance. It’s strenuous and a balancing act.

I did get lucky in that it’s set in a certain period and place in Japan as World War II was starting. My mother was actually born in Japan outside the Kansai region and is probably within one year of Mahito’s age. I understood something of the flavor of the world. I was able to impart that context to the actors that came in. I realize I’m a white dude talking about all this stuff. I grew up watching people of certain age really relate to my Caucasian mother because she was there right before an impactful time for the entire nation. Because my mother was there before the bomb, she was on the inside track of a lot of things. Getting to have those conversations with people was really useful. But what Hayao Miyazaki is saying within the context of the entire film, that’s a whole other thing.

Dar: I’m a big James Gunn fan. One of the things I admire about him as a filmmaker is the way he cultivates close relationships with his cast and crew, hence why so many people are eager to repeatedly work with him. Much like Gunn, there are actors in the English dub voice cast for The Boy and the Heron you’ve worked with on previous projects and some you’re working with for the first time. What’s your approach to fostering a positive experience for actors in the recording booth?

Michael Sinterniklaas: That’s funny. I’d be really curious to talk to James about his experience doing that. Something I love about his work is the playful nature that you can feel coming through the final work. Peacemaker is [a] clearly funny and boy humor show but it’s so much more than that and transcendent. The playful nature of doing the work is something that’s been really important to me forever. My background is classical theater. I went to a conservatory. I think one of the most important things of doing the work is staying playful. One of the things I have done throughout my whole career directing people is to be open to the opportunity or even nudge outtakes. I think that’s fun for creativity.

One of the rules I have in my booth is it’s an apology free zone. I think you really interrupt the sense of play when you start feeling like you did something wrong or the sync is off. Dubbing is so technical. I want you to feel like you’re still playing. I want you to feel like you’re still discovering all the moments you have to discover for yourself rather than be told to do it this way. I’m always playing. I make fun of myself tremendously whenever possible because nobody is meeting to try to build chemistry. I record little outtakes and messages for each other. I played some stuff of Luca [Padovan] for Florence Pugh. She recorded something back for him. It’s really cute. One of the “obas” had a moment with Shoichi and we had Christian Bale play him. At one point I have her going, “You’re just too damn cute, Christian Bale!” It’s funny and sweet. I don’t want to seem like we’re not respecting the work. I think by keeping a sense of play you can best honor the work because you’re keeping loose and creative. Outtakes is one way of doing it.

One more playful thing in the booth. When Mark Hamill came in, [English script adapter] Stephanie Sheh brought her dog Ippudo to the studio and he liked playing with the dog. So I think a dog is really helpful.

Sinterniklaas: When Dave Jesteadt from GKIDS first saw the film, he saw it without any audio. When he saw the design he was like, “Something like Danny DeVito.” Ghibli said their actor [voicing the Heron] was 30 so to go with something like that. We were throwing names out. It’s funny because some of the hot young actors have a really cool vibe but the Heron is far from that. It was a tricky thing to cast. When GKIDS came up with the idea for Robert, I thought it was interesting. We all agreed he is a fine actor and transformative but he had never done anything quite like this not just in voiceover. His tempo in most of his stuff is so different. He can be erratic and eccentric and he plays a lot of mad men. This is a different kind of energy. I got to keep giving Pattinson some credit. He did the work at home, for which there is no substitute, and just showed up with a recording on his phone with the voice he had been working on. It was there. All I had to do was split it between the two modes. Ghibli had the note when he’s in his bird mode he’s much more theatrical and grand. And when he’s in his man mode he’s the other little shyster guy. We found those levels with the voice he brought and then we were done. Rather than have to create the character, because we don’t have a rehearsal process, he showed up to do the job and ready to go.

Michael Sinterniklaas: It restores my faith in humanity that we recognize things that are good. It’s a fine work. [Hayao Miyazaki] is a living master in our time. When Guillermo del Toro introduced the film in Toronto for TIFF, he said, “We’re so fortunate to be living in a time where Mozart is still composing and conducting. The van Gogh is releasing new work.” I’m just glad he’s getting the recognition. So often, like van Gogh, these people are appreciated posthumously and I’m glad that he gets to see how many lives he touches. I know he doesn’t look back at his old work. I wish he did, and I wish he would do a commentary track for this because there are so many questions.

I used to think in my youth that when a director said, “What did it mean to you?” that it was a lazy answer. But I appreciate it in this case. I think Hayao Miyazaki is the director that taught me this. When you release the work, it belongs to the world and it’s for them to interpret. He has such a fluidity of being able to let his subconscious drive take the wheel with something so crafted as animation, that he does us a service by letting us receive it as we will. He tells a story about his father, his mother, and his experience. And then we get to relate that to our own. The first time I saw the movie I was thinking about my mother whose experience was somewhat similar to Mahito. I get to receive it personally because he speaks so fluidly in the unconscious vernacular. I think that’s part of what makes his art fantastic. I wonder if AI could ever do that. [Laughs].

Dar: It’s been an immense pleasure chatting with you! I have no doubt that The Boy and the Heron is a lock for a Best Animated Feature Oscar nomination. Whether or not it wins I don’t want to jump the gun since it is up against so many fantastic animated films that are just as equally deserving.

Michael Sinterniklaas: That would be extraordinary and so great. He didn’t win for his last “last” film, The Wind Rises. We were up against it with Ernest & Celestine for the Oscar. I didn’t want to take it away from him for his last film, but it all went to Frozen.