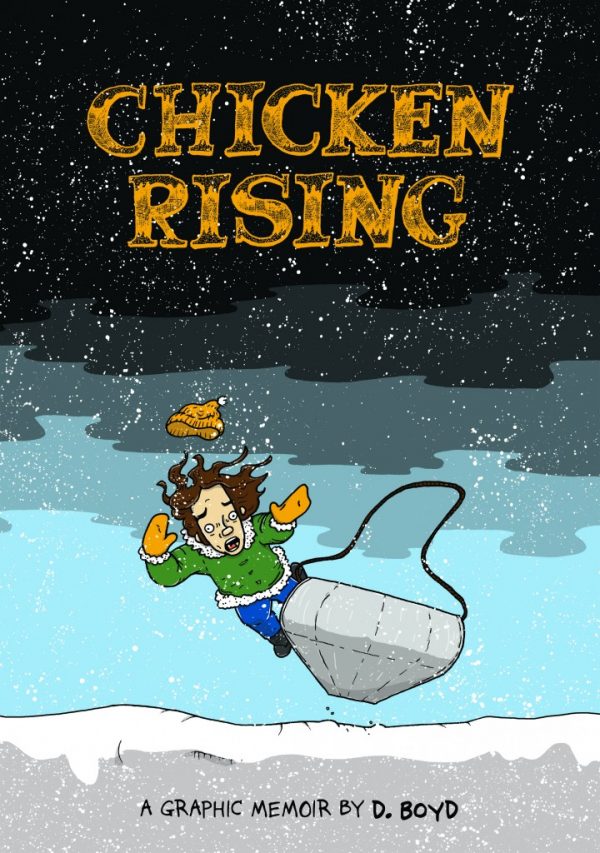

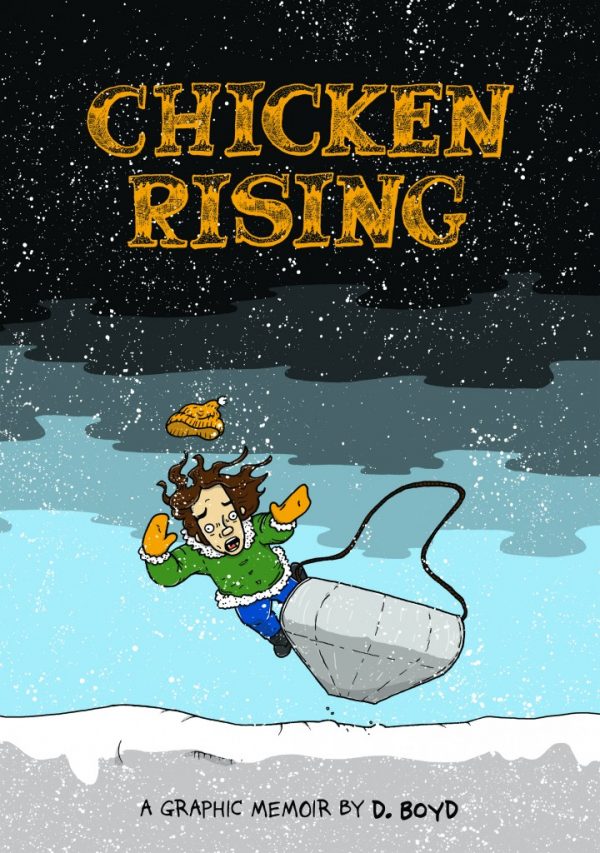

Cartoonist D. Boyd lives in Montreal now, but she grew up in Saint John, New Brunswick, and the area nearby, in the 1970s, and that’s where Chicken Rising, her graphic novel memoir from Conundrum Press (which I reviewed for the Beat) takes readers.

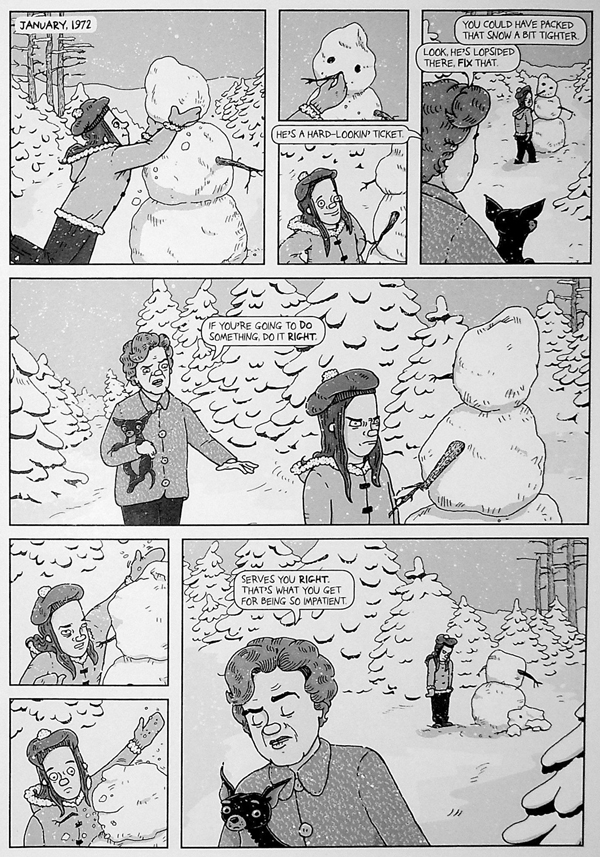

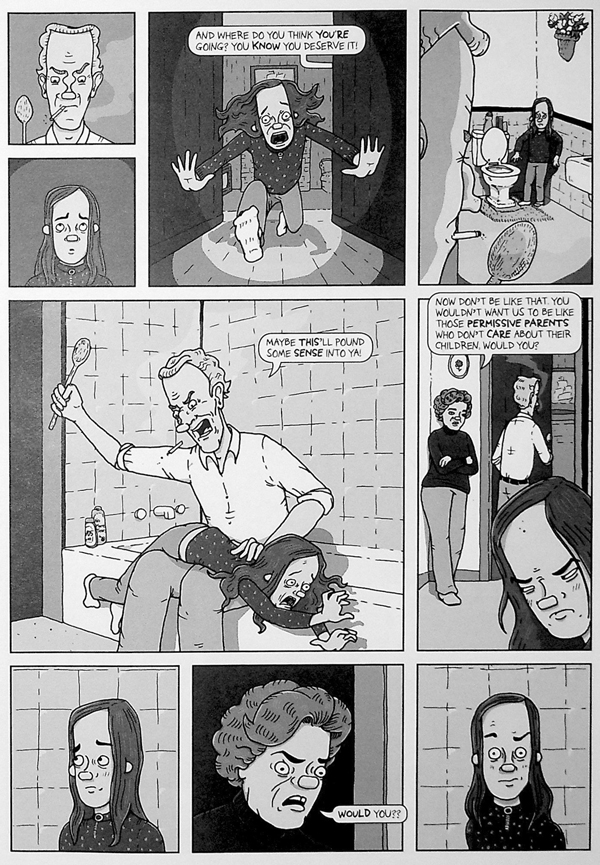

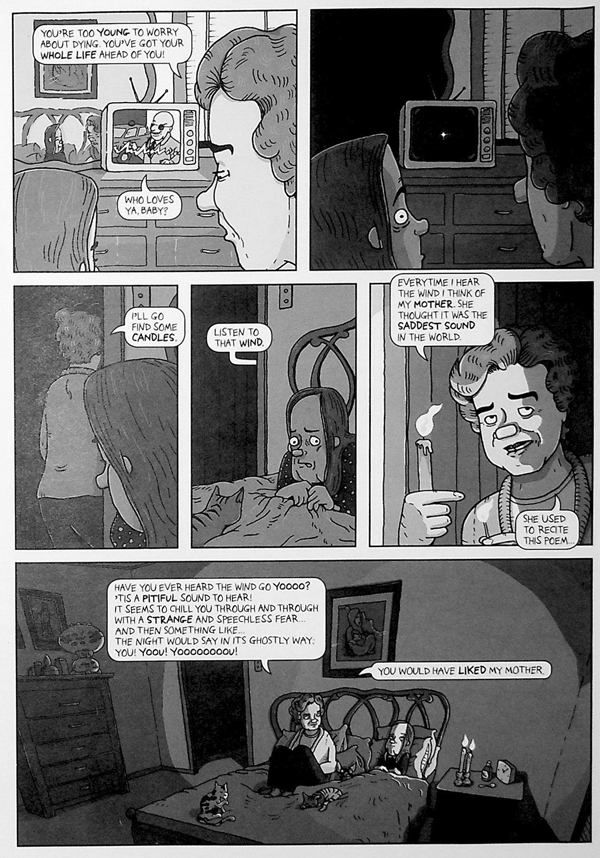

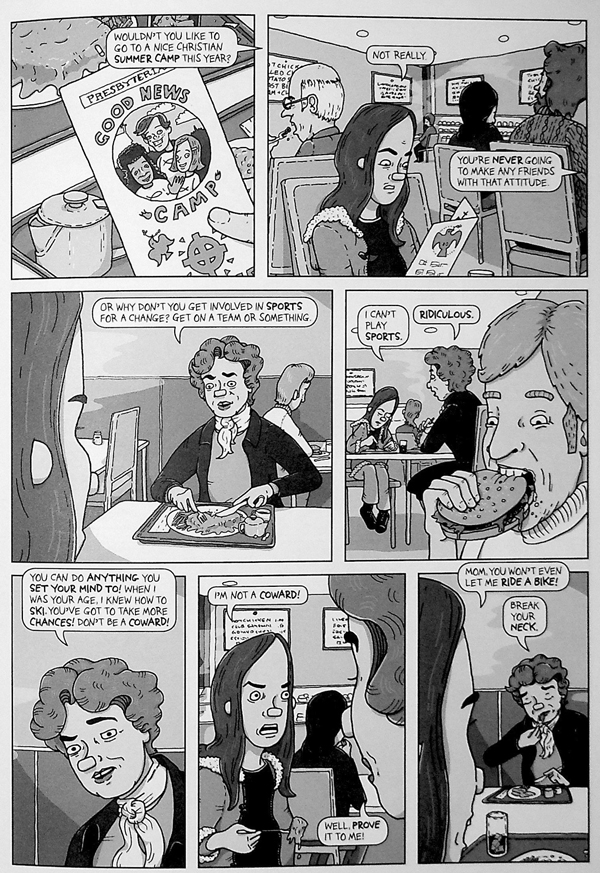

Beginning with her preschool years and moving through sixth grade, Boyd anchors her memoir in the frequent clashes between her rebellious awakening and her mother’s dysfunctional method of dealing with the challenges Boyd presents, which is mostly to try and squash her spirit through constant criticism. But Chicken Rising doesn’t portray Boyd’s mother as a one-dimensional villain, but rather a multi-faceted woman for whom being a parent was an unexpected and continuously difficult challenge.

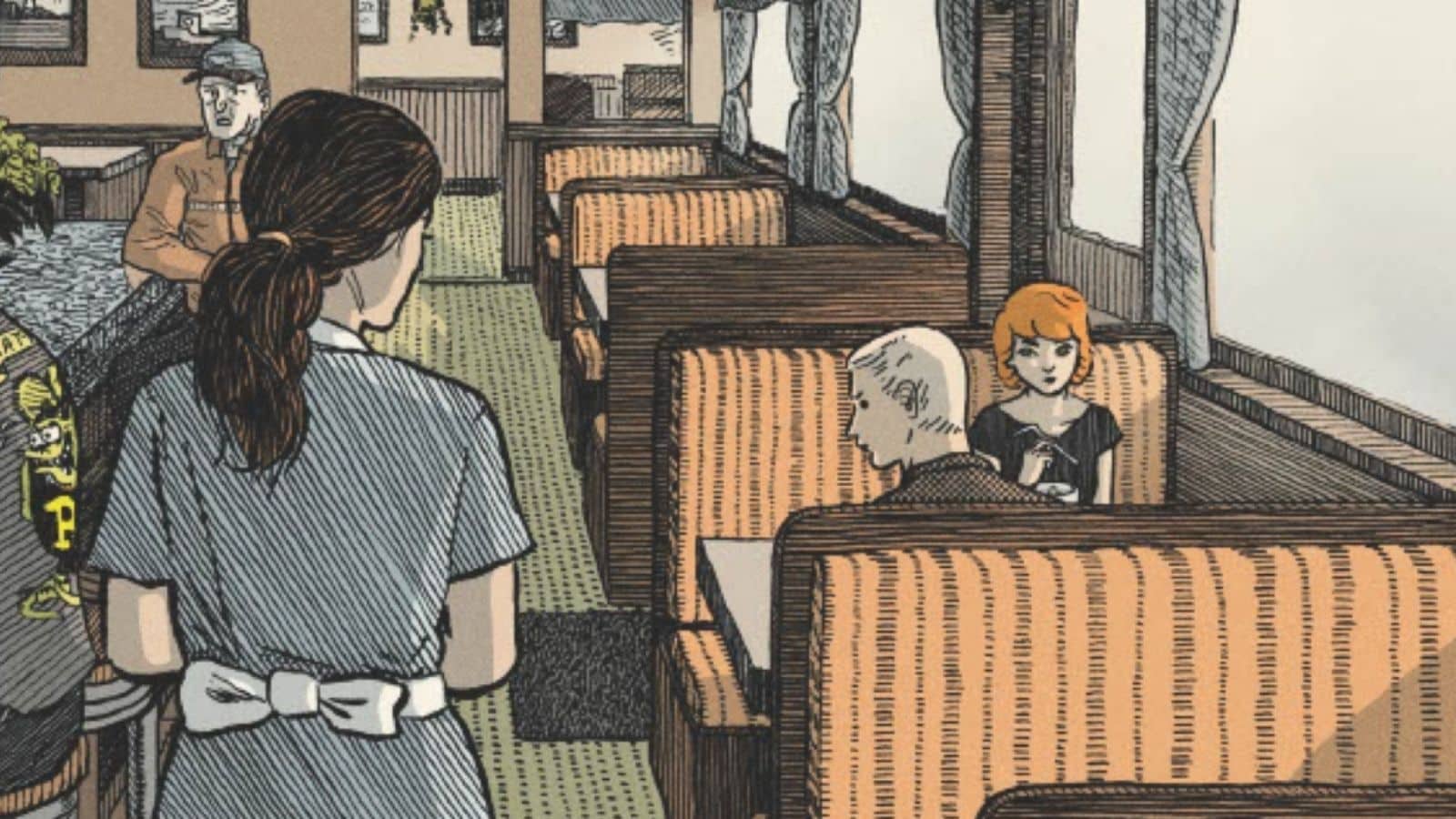

Chicken Rising starts begins with her parents opening a chicken restaurant, which they owned in Saint John from 1970 to 1983, and presents a candid, episodic collection of amusing and horrifying incidents that add up to a larger truth about her childhood.

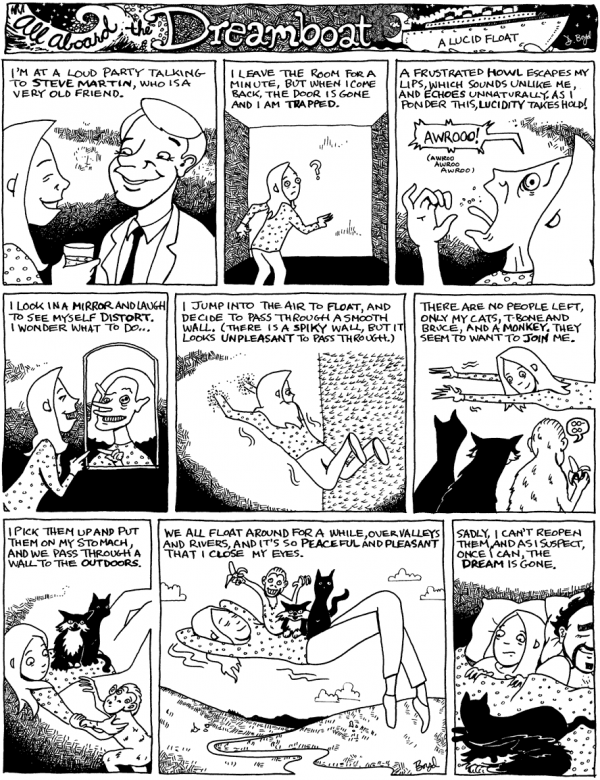

Chicken Rising is also the story of why it took so long for Boyd to create a graphic novel. Cartooning was discouraged in her house and ended up being the road she never took. Eventually, she worked her way back to her first love, starting with a series of webcomics and then directing her focus to Chicken Rising.

—————-

This is considered a later life debut for a graphic novelist. What were you doing before Chicken Rising and what took you so long to get to it?

I’ve always drawn comics as long as I can remember. I loved drawing comics but I never took it very seriously. As evidenced by the book, artistic pursuits weren’t really encouraged. So I didn’t even consider it as a real pursuit when I was younger. And then I went off to university and didn’t like what I was doing there either. I ended up dropping out three years into it and getting a job, working at a newspaper, doing layout, and then got stuck working. How can I stop and go back to school and change my life when I’m stuck working in advertising? And I really hated it.

I probably would have continued to be freelancing in advertising had I stayed in the Maritimes, but then we moved to Montreal and I just couldn’t find work. I just took it as an opportunity to go back to trying to do comics, but tried to take a little more serious approach to them this time around and putting more of a genuine effort into it because I realized I’m getting older, I never figured out what I was going to do when I grow up. It’s now or never.

About eight years ago, I started doing more comics. I had some webcomics going and trying to get some little zines out and that wasn’t really going very far. I’ve always wanted to do a graphic novel. It boiled down to I’m an only child, I’ve got no kids. And I realized that all of my stories are just going to vanish into thin air when I die. You know, everything I’ve got to tell is just going to go away. So I wanted to do it as a sort of a record or a testament to childhood. And it wasn’t too in intention to demonize or idealize. It is just to show the foundations of future adult behavior for better or worse.

When you sat down to start working on Chicken Rising, had you given a lot of thought to the issues you raise in it or was it a lot of stuff that came out as you worked on it?

I guess I had given a lot of thought to the issues I’ve raised. They were all always stories that have been rattling around in my head for as long as I can remember, so just getting to finally put them all in one place and get them all out on paper was the goal. A lot of people have asked me if this is a cathartic thing that I’ve worked through, like a therapy thing and it really wasn’t, because I feel like I’ve worked out all that stuff, but it did put some closure to that dialogue that was always going on in my head with my parents and with my past self.

And there was also a lot of motivation in that it has to do with themes about being an only child and everyone having an idea of what that means. It’s amazing how many people with siblings know what being an only child is all about, you know? And, yeah, so just ‘oh, your life, you get advantages, you’re an only child’ and wanting to get it out there that that’s just another stereotype and misperception.

I ‘m an only child, so I definitely get that aspect. Do you find it easier to deal with the dysfunction of your family because you’re an only child? Does it lend you some freedom or give you some insularity to help you deal with things?

That’s an interesting question, partly because I suspect it would have been slightly less dysfunctional had I siblings. I just have a feeling because my parents had me as a singular focus and they had their issues.

Certainly, as an only child, you find yourself in an observer position a lot. You’re not constantly interacting with someone else because there isn’t someone else to always interact with. So you’re observing. So maybe in that sense, it always gave me a little bit of a way to deal with it because I was always assessing it and wondering, why am I so different from them? And without having that immediate other kid right there to relate to.

That also raises the question though. Is being an observer in this situation what equipped you to do a book like this? And if you had siblings, would you have been the same person who could do this book?

That’s a good question. I mean, it’s hard to say since I don’t have anything to compare it to, but I suspect it has a lot to do with being an only child, with being the type that was always assessing what was going on. But like I said, it’s hard to compare because I don’t really know what it would feel like to be somebody who was raised with siblings. For example, I know if my parents were still alive, I probably wouldn’t have done this. But on the other hand, it’s partly because they’re dead that I was compelled to do this, to bring it all back to life before it all just vanished.

Did you have any other family that maybe you were worried they would see Chicken Rising?

Yeah. There’s only one living person who was one of the older characters in the book, one of my aunts. She wanted to see it and she was so excited about seeing it and I was so worried about showing it to her.

Finally, I couldn’t ignore it anymore. I had to give her the book. She’s 96 now and it ended up she just loves it and she’s just so happy to see herself portrayed in it. That took a lot of worry away.

It’s funny because I’m finding the way the reviewers are seeing the book, it seems to be a little heavier than I feel about it myself. I’ve already worked these issues out. They’re old rehashed stories to me. So to me, they’ve lost some of their grim aspects. And I forget that maybe when people see it today, especially with the climate today, when people or children are much more respected than they were in our era, they’re really horrified and ‘oh my God, this is terrifying to see, a kid being physically punished,’ and that sort of thing. Whereas to me, those are old stories, old old stories that have lost their total impact.

I find it interesting the way Chicken Rising is structured presenting a specific slice of a specific time sequentially to sort of show the wider picture over a number of years. Was it easy to come up with the specific moments that you wanted to portray or did you have to really search your memory for some of them?

That was quite a struggle. In order to do this, I started by writing down the obvious significant memories that I never forgot about. And then I started to keep lists of every possible memory, every little fragmented bit, everything I could think of, things my mother would say, vernacular from New Brunswick, what was on TV, every possible memory. And I started just jotting them all down and drawing them and then I would sit with it and just take elements and say like, how many of these things can I combine into one story? And at the same time trying to create more or less a narrative arc of the whole thing.

So it was a real challenge to be as true to the memories as I possibly could be even considering I had to merge a bunch of them and force them to fit into a timeline that eventually had a beginning, middle, and end. So it was months and months and months of juggling and revisions. I must have had 14 script revisions at least. It was really quite something. I had to cut it all up into pieces and glue it all to the hallway wall to keep juggling parts because it would become overwhelming trying to wrangle it. And it continued to evolve right up to the very last stage as well.

Someone was asking me about why I did it chronologically and I was thinking that, at first, I tried to jump back and forth through time and I found that wasn’t adding anything except confusion. I found that when you do a memoir, especially of childhood, chronologically, it’s kind of like watching a timelapse. You can see the effect of what’s happening more obviously, I find that it has that time-lapse feel.

Did you ever take out incidents that you intended to use, but maybe you thought either they didn’t fit in for whatever reason?

I did. There were many things, like, for example, some precious memory that I really didn’t want to leave out, but it didn’t fit anywhere. It didn’t have any narrative. The only thing that made it interesting was just because it was a personally special thing, so I had to leave stuff like that out. Some stuff was just a little too grim and too dark. I left that out. I wanted to have more of a darkly humorous feel than a seriously grim thing. Some things just had to be left out for sheer repetitiveness or they didn’t sit into the storyline. Although at this point I regret slightly … well, I feel like I should have included a bit more of the happy times.

I could see that. On the other hand, the way you do it with your mother, you acknowledge a lot of her own story that’s going on in her head and explains some of the things that you might look at as the negative parts of Chicken Rising. And also you do include positive things about her. But that strikes me as an awful hard balance to get down on paper.

It was, it really, really was. I spent a lot of nights laying there awake, just shaking my head over the guilt of feeling I’m exposing too much or that I’m just demonizing and it’s just going to turn out to be another Mommy Dearest kind of thing. Or just airing grievances and complaining and not getting enough of what made her a complicated person, an interesting person that wasn’t just bad or good. So yeah, that was quite a struggle, that part. And she was very contradictory and unpredictable in her behavior, so I had to get that across too,

It seems like as a kid you never knew which mother you were going to get at any moment.

Yeah, that’s true. But we spent a lot of time together. I believe one reviewer mentioned something about hostility or something, but she really wasn’t hostile. She just had her own baggage and the lack of experience of motherhood. She was another person like me who didn’t ever expect to become a parent. It just wasn’t in her expectation. She had me when she was 42 and back then, that wasn’t really common. So she just stumbled into motherhood and then tried to muddle her way through it and she didn’t have any help from my father, so it was all upon her.

I realize that with sympathy and empathy toward her now. I guess that’s another thing, writing it now in my fifties as opposed to even if I had done it in my forties or especially if I had done it in my thirties, not that I would’ve had the skill to do it, but it would have been angrier. I hadn’t worked my stuff out yet, so it would have been therapy back then and it probably would have been more angry stuff about my mother, still blaming her for this, that, and the other thing about how I turned out. But now I’ve learned how to deal with it. When you accept yourself, you have to accept everything that made you who you are. I’ve come to a much greater stage of empathy toward her and even my father now. So that was one of the things I really wanted to try to show that they were human too.

It’s kind of a cliche that you brush off when you’re young, but I’ve found when you hit your fifties, you do have enough life experience that you develop a different perspective about other people’s behavior, really different from what it was 25 years before. Age actually is knowledge in a surprising way and that must make it easier for you to do a book like this too.

Yeah, I agree, that’s true. I’m sure it would have been much more muddled and I wouldn’t have known how to end it.

What was your relationship with your parents like after the book ends in the sixth grade?

At that point, I just started breaking away from them. Everything was behind their backs at that point. Junior high was a lot of fun, one of my favorite memories. I’m really, really nostalgic, which is also of course why I did the memoir. But yeah, that was a really fun and rich time. And what I remember most about that era is doing everything behind my parents’ backs. Everything was clandestine. Everything.

Do you have any plans to cover that era in a follow-up?

I’m waiting to see if this one is going to go over well or not. It took five years to do this book. It took almost as long to do it as the time period of coverage, so I’m never going to catch up at this rate.

Saint John, New Brunswick, not St. John (yes, I know, but it matters to Canadians and to the folks in Saint John, NB and St.John’s NL)

Nice.

Comments are closed.