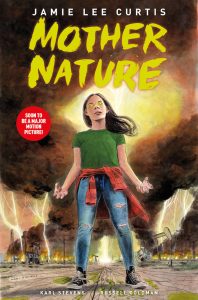

In Mother Nature, written by the Academy Award-winning scream queen Jamie Lee Curtis (Halloween, Everything Everywhere All At Once) and her partner-in-crime Russell Goldman (Return to Sender, Closing Time) and illustrated by Karl Stevens (Penny: A Graphic Memoir, Guilty), Nova Terrell undertakes a personal vendetta against the Cobalt Corporation after her engineer father dies under mysterious circumstances. But when her thirst for monkey wrench justice leads her to discover and awaken an ancient and long-dormant spirit through the “Mother Nature” project, she realizes the stakes are even higher than she knew.

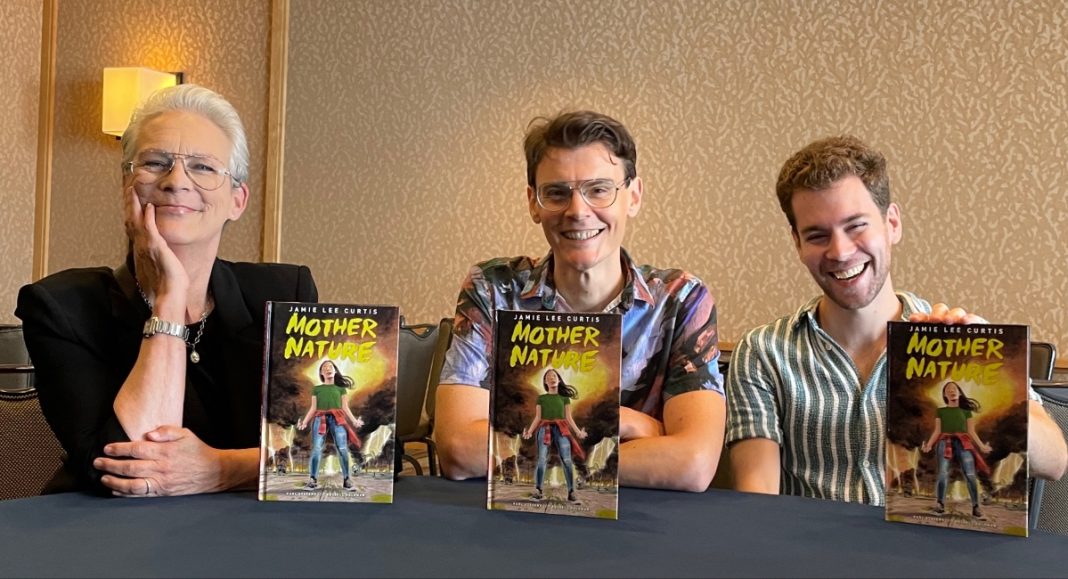

The Beat caught up with Curtis, Goldman, and Stevens in July at San Diego Comic-Con 2023. We asked all about how Curtis and Stevens first met, about the cinematic and artistic influences for Mother Nature, and about setting the story in a fictional area of New Mexico.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

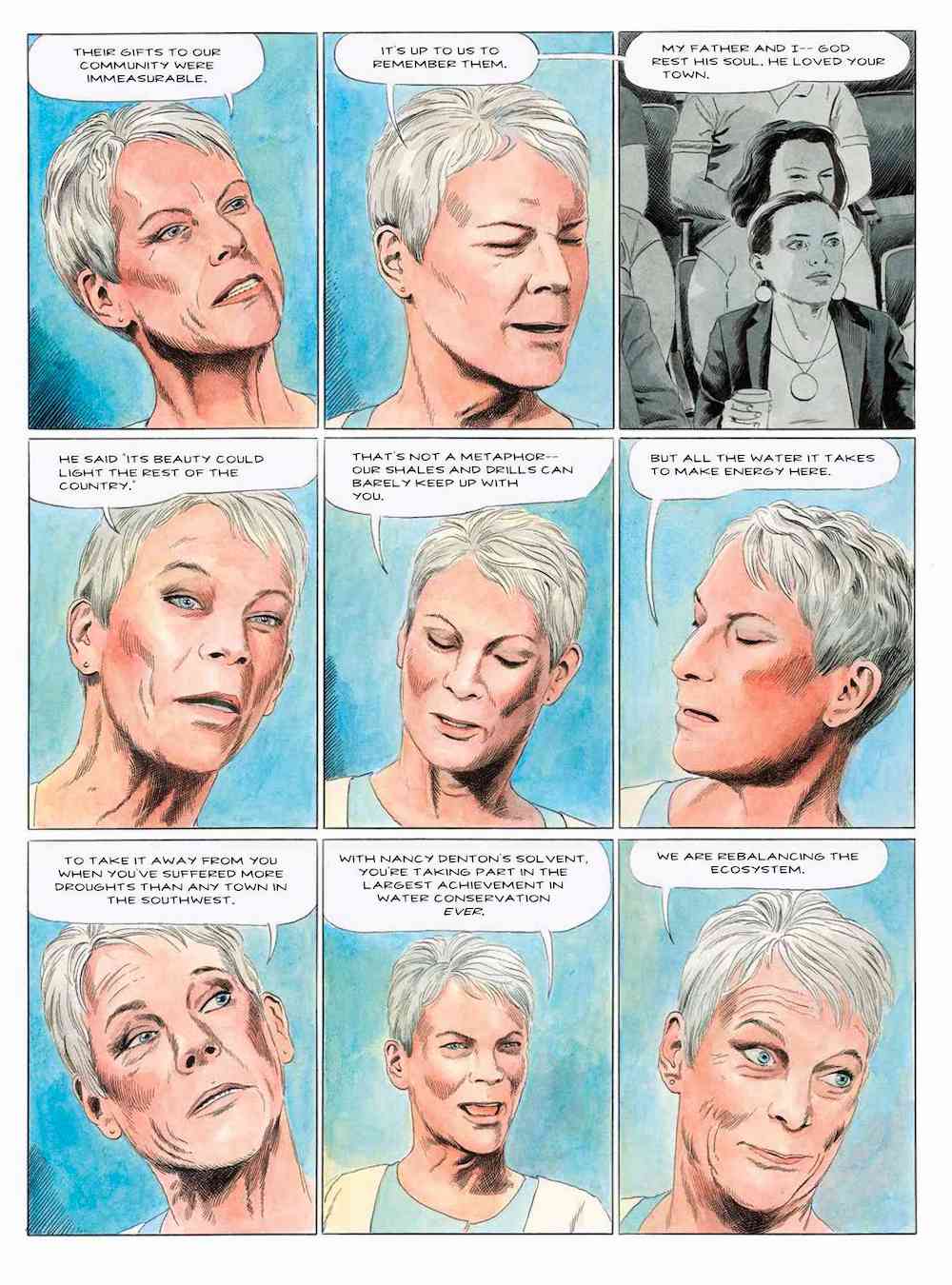

REBECCA OLIVER KAPLAN: Did Karl Stevens use reference photos for Mother Nature? Did you pose? [There is a Mother Nature character who bears a striking resemblance to Curtis; see below.]

JAMIE LEE CURTIS: No. So that you know, Karl and I have known each other for four years and never met until today—it’s true.

KAPLAN: How did you meet Karl? I know your husband Christopher Guest gifted you one of his New Yorker cartoons.

CURTIS: So, how I met Karl is that’s my husband gifted — no, my husband didn’t gift, I gifted. I’m the gifter. My husband’s a good guy, but he’s not the gifter. When we got married 39 years ago, for our wedding, I gave Chris an original New Yorker by Bob Mankoff of a couple driving away from the church with the husband turning to the wife and saying, “Mind if I put on the game?” and it was entitled “The First Straw.” Because I’m a baseball widow, you know, my husband watches a lot of baseball.

And so we’ve collected them over the years. This year was our 35th wedding anniversary. I had seen a cartoon in the New Yorker of Humphrey Bogart sitting in Casablanca at a bar, a beautiful line drawing, a fine line drawing, and the caption was, “Alexa, play ‘As Time Goes By,'” which made me snort-laugh. I contacted Karl to buy the original pen and ink drawing because I buy one yearly.

We started talking about what I was currently doing, and I mentioned the story that Russell and I were working on. He said he’d love to read it, and his first response was, “It’s great Jamie, I think it’s a graphic novel.” Titan quickly agreed, and here we are.

KAPLAN: I was excited to see that Mother Nature was done in watercolor.

KARL STEVENS: Yes, it’s all hand-painted.

KAPLAN: What were the challenges of bringing that to life?

STEVENS: Well, there were many. When I got the script, I thumbnailed it, basically doing an elaborate storyboard treatment to it all. Then, I started collecting images I thought would be appropriate and got some friends to model based on those thumbnails.

It’s very similar to making a film. I’m a big film fan anyway, so I feel like my work is cinematic in quality. So, I tried to bring all my knowledge from that type of storytelling into this story.

I also studied fine art. So, I wanted these beautiful vistas reminiscent of 19th-century romantic landscape painting, which I thought would be essential to mix with all the gory stuff.

KAPLAN: Did you incorporate Southwestern traditions into Mother Nature, too?

STEVENS: Yeah, I’d visited before but went again to see the landscape. I looked at a lot of Southwestern painters from a long time ago when people were first starting to go out to New Mexico. When the country wasn’t quite as developed as it is now, it still was this pure, beautiful, pristine landscape—that was essential to the story to have the panels look like what nature should be and not how it’s been completely degraded.

KAPLAN: It‘s set in an entirely fictional area, right? [While the graphic novel is set in Catch Creek, NM, Cache Creek is a real place.]

CURTIS: The names were invented. We were talking about the fun of seeing Nova Terrell become a real person visually when we made the name up—it was so much fun.

One thing I would like to say about the natural landscape in the graphic novel is that there was an indigenous population of people born and raised on that land, and they revered it. Land was their mother. And we have come along and degraded it. We degraded these human beings into nonhuman beings. We made them irrelevant and tried to erase their history, culture, and legends.

What was so beautiful for me in this story of how the graphic novel came together is that in my natural storytelling, I used the word Native American, but that was about it. But Russell spent months doing the heavy lifting, and I want you [here, Curtis turned to gesture at Russell] to explain how you approached the emotional, cultural narrative like Karl did the visual narratives.

KAPLAN: You worked with five Diné advisors, correct?

RUSSELL GOLDMAN: Yes, but not all Diné. We started this process about four or five years ago. Not just Jamie and I writing the story but also talking to people who worked in oil, environmental lawyers, and people on the ground in New Mexico.

We imagine Catch Creek is somewhere between Farmington and Sawmill, and we wanted it to feel accurate to that part of the world. It was a process with some of our Diné advisors, Jeremiah Watchmen and Brian Lee Young, who wrote the afterword to this book. It was a process of not just, “Hey, are we doing the right thing,” but a relationship that was built and has now existed for years. Because we are three white creators, we wanted to convey our intentions as honestly as possible.

Brian, and I know he’ll be happy with me sharing this anecdote, said, “I’m happy to work with you, but I need to hear first why you guys are telling the story.”

I said, “The thing that is very important to me, Jamie, and Karl is that this is an emotional story about the world that one generation is choosing to leave behind or create for the next generation.” And that is something that, obviously, anyone alive, and let alone anyone who lives near Four Corners, New Mexico, can relate to, and he loved that.

That led us to create a story that did not have a Western conception of nature but instead used the Naayééʼ, the enemy of the people, to use a piece of the Navajo creation myth respectfully, making sure the language is exactly right, making sure the context in which we use it is correct. Because these are stories that are largely orally translated…

CURTIS: They call it “talk story.” It is passed on through generations through talking. As you said, we’re three white people telling the story and want to be mindful. Russell has been incredibly thorough and patient, and Karl had to be patient because we had to go back to some of the panels that had already been drawn when we hadn’t gotten it quite right. Through more information and more detail, we had to redo it.

Titan was also patient when we said, “We’re going to delay for three months because we have to go back.” Because it’s the same thing for them, they want to be able to produce and publish something accurate. And I’m just proud of the team, and I include Titan in that, because everybody wanted to get it right. Carl wanted to get it right. Russell very much wanted to get it right.

And I, as the face of it — because whether or not you agree that I’m the face of it, I’m apparently just scared the literal face of it — that we all wanted to make sure that we honored the very people that we were trying to talk about and save.

KAPLAN: I am curious because you’ve had the story in your brains since you were 19, and so much has changed in the world of climate, like climate change and climate policy. And especially since it’s a generational story; you specifically brought up Greta Thunberg. I’m curious how that story has kind of evolved in your mind over time, or this story?

CURTIS: Well, as you know, we we’ve figured out new ways to rape the land, is what has occurred. We’ve gotten tired of or we’ve drained the land of certain resources, and we just go, “Well, let’s come up with a new one.” And it’s obscene. I do drive an electric car but I mean, I’m doing my part, but I’m not a perfect person. My carbon footprint isn’t perfect. But we’re all mindful. We’re all thinking about it.

I once talked to somebody about air travel, and what a big problem the amount of air travel is. And I said, “Well, nobody’s going to stop flying. People aren’t going to stop that.” But he said, “But if people stopped eating meat, it would change everything.” And he said, “That does seem like a possibility.” 10 years ago, if you’d said that, people would have been like, “They’re crazy. That’s never going to happen.”

And you know what? People are changing. People are starting to wake up to that idea, that meat production is a big contributing factor through the methane of of the climate crisis. And so I do believe change is possible. I believe that we can change. Mostly I think we can change through art. And how it’s evolved is just how it’s evolved.

We’re at a crisis point, and it’s clear where to crisis point. We’ve had the hottest summer on record. We’ve had the most rainfall on record. It is a catastrophe. It is a catastrophic situation. And we have made something through art to bring awareness through graphic violence, scary, bloody, gross, beautiful, gory, fabulousness.

(Featured Image: Rebecca Oliver Kaplan)

Mother Nature is available at your local bookstore and/or public library now.