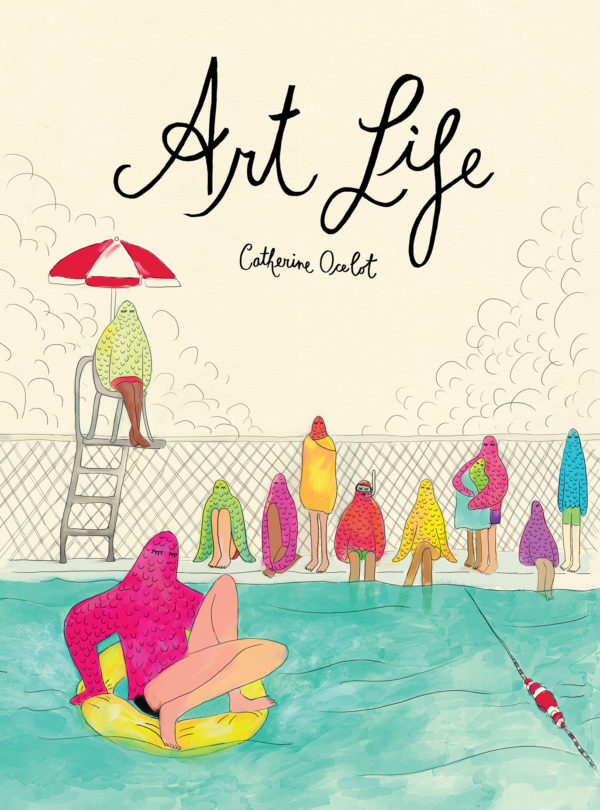

Art Life

By Catherine Ocelot

Translated by Aleshia Jensen

Conundrum Press

Catherine Ocelot is trying to figure things out. You could say that about anyone, of course, but what Ocelot is delving into are the concerns of an artist, which is actually part of the creative process. Questioning, searching, these are components of the work to be done. But it’s not always a formal process and Ocelot demonstrates this in her graphic novel Art Life, which reveals it’s far more casual and far more ingrained in other aspects of life than people not in a creative field might imagine.

As Ocelot navigates her own creativity — her intentions toward her next project, what she wants out of it, what shape it will take, what challenges it presents — she has a number of conversations that have meaning to that goal, though it’s not always directly. Sometimes she talks about her next project, other times the conversation covers general issues of creativity and trying to live a life that includes time for making art.

Sometimes the process and the conversations challenge self-esteem, as when “the president of a university” approaches Ocelot poolside and at first elevates her ego only to deflate it shortly after, without ever realizing the effect of the turn in conversation. Self-esteem and the battle to keep hold of it is a recurring subject in these conversations and something that nags at Ocelot’s process, something that any creative person will no doubt recognize in themselves.

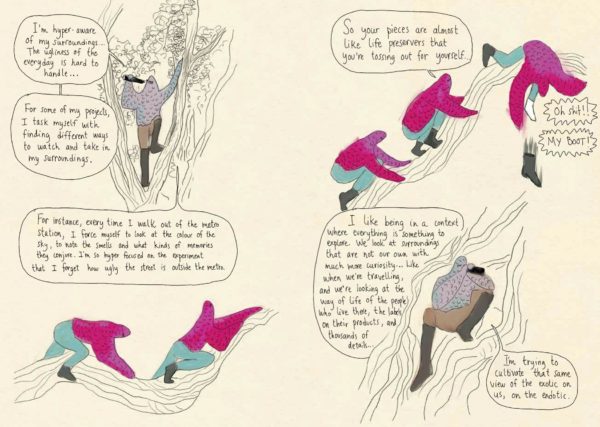

A lot of the self-doubt visits Ocelot and the rest of us in the form of professional considerations, which have a unique power to strike you down. One conversation features Ocelot pitching a new project to her publisher, not getting the supportive reaction she had hoped for. During an encounter with an artist friend which takes place climbing around on telephone wires and trees, the conversation turns to ways an artist can expand their approach, engage with the world, and tap into philosophical focal points when creating their work. Ocelot grapples with these issues and the action on the wires and trees give a visual cue to the clumsiness she feels, requiring assurance and assistance from her artist friend, though it may not be to the degree she needs it.

Often the conversations with other creative people seem to be a blend of helpful recognition and demonstrations of the distance between the conversants. In one conversation that begins with the shift from being a big deal in a small place to being a small deal in a big place, the talk moves to the challenge of dealing with successful friends and the complex emotions it brings up. But when the friend enters into a “woe is me” soliloquy about their position in life, Ocelot challenges that as nicely as possible, suggesting that this person might be considered the successful friend by others and not realize it. Reasons are given why this is not so and I don’t leave that chapter convinced at all, yet I understand why people need to believe that is true.

Sometimes the conversations in Art Life address not only the issues of being an artist, but actually saying that you are an artist, and how others perceive that. In one chat, Ocelot’s friend goes to great lengths for distance from making that proclamation since, as a film producer, the job is to help the artist blossom. The producer believes that the most important aspect of the job is to not want to be an artist, that the desire to be an artist cuts through the ability to contribute as a guide to the artist. That requires the ability to stand back and accept ego as a crucial defense aspect of an artist that is something you need to work with, not despise. It’s actually advice that an artist could take to heart and use as inspiration for self-analysis.

Questions about autobiographical work also come up. One interesting conversation addresses the ethics of including other people in the work and moves along to the question of how personally an artist takes criticism of autobiographical work. Are you and the text different things? And how does this affect relationships? It is suggested that there are conscious choices that need to be made about friendships, that is whether a person is helpful or destructive to your creativity. There is also the question of how much of yourself you really want to put out there. Should there be a part of you that is closed to the public even though your work is about yourself?

A later conversation furthers this with a discussion about creating a professional persona in order to shield your private self in a less-complicated way, and one near the end of the book with an older friend reveals these struggles never go away.

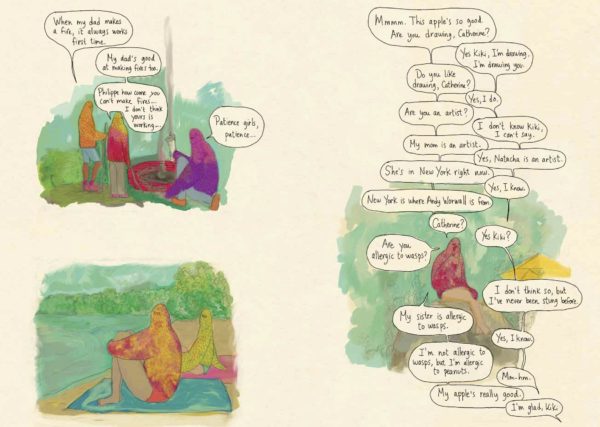

At one point Ocelot presents her attempt to watch the film Interstellar, interrupted first by a chaotic phone call from her mother and then her daughter coming into the room and asking questions. It illustrates how you don’t control how other people encounter your work once you release it into the world. I’m sure Christopher Nolan put a ton of thought into his film, just has Ocelot has demonstrated the amount of energy that goes into conceptualizing a project, but all that is discarded as a concern when your work is set free.

But Ocelot also takes time to depict the reasons why it’s difficult to make these stark lines in her artistic pursuit — family. Or, to be more specific, children. They create chaos in a structured artistic practice by the very nature of their being. They don’t care about any of the topics you’ve discussed with your creative friends or if you try to compartmentalize these aspects of your life. They ask questions when you’re not ready to answer them. They interrupt when you need that moment. They need you when you’re riding a wave of inspiration. And they keep the need to create something you fight for rather than settle into.

It’s a heady concept for a graphic novel, but it all unfolds conversationally with a sly sense of humor. And Ocelot’s charming artwork dispenses of any prejudice you could bring to the people expressing their opinions by depicting them as bizarre, faceless, not-quite-human figures. Their bottom halves are legs, but from the waist up they are differently-colored, feathered or scaled and formless creatures. And that’s kind of what we all are anyhow, half-way there, seeking some clarity but always in motion and never quite achieving it.