Camouflage: The Hidden Lives of Autistic Women

Written by Dr. Sarah Bargiela

Illustrated by Sophie Standing

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Surprise! Women who believe they might be autistic report that when they seek help, advice, diagnosis, they are often not taken seriously and are given alternative suggestions for what they are noticing about themselves. That’s just one of the pieces of information that should be a surprise in Camouflage: The Hidden Lives of Autistic Women but sadly is not.

There are a lot of people with autism out there nowadays — 1 in 59 children is diagnosed. The popular perception and the information that results because it focuses on males, with the statistic that 1 in 37 will be diagnosed. In contrast, 1 in 151 females will be diagnosed, so that could explain the information skew toward males.

However, Bargiela suggests there may be other issues, including differences in the manifestations autism between men and women that aren’t taken into account and lead to misdiagnosis, as well as differences in the way women cope with the symptoms.

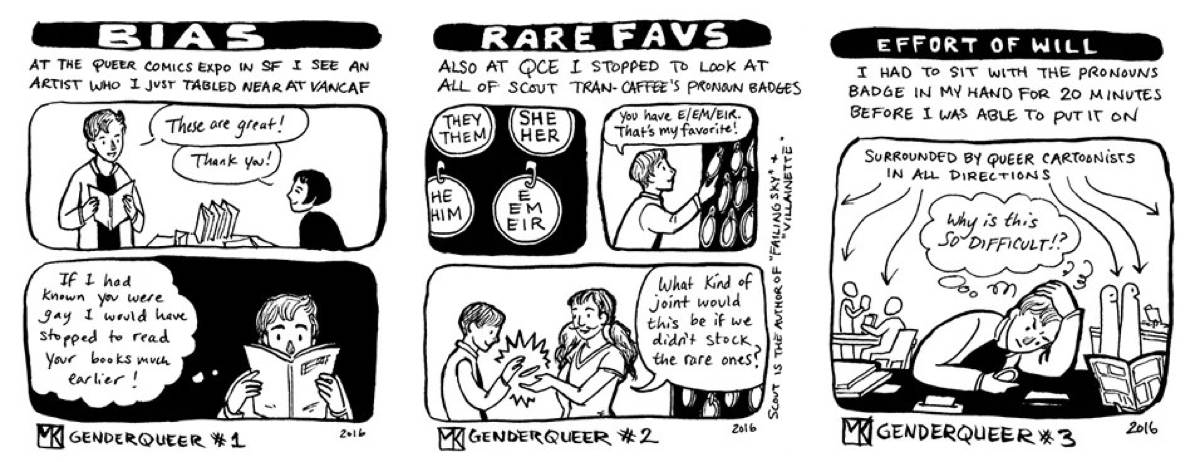

Now you may wonder how such a dry subject — interesting, definitely, but dry — can translate into a graphic novel form in a manner that makes it worth picking up even if autism is not something that either personally affects your life, or at least is an area of interest already.

Easy. It’s the personal stories of women with autism and the insight they provide.

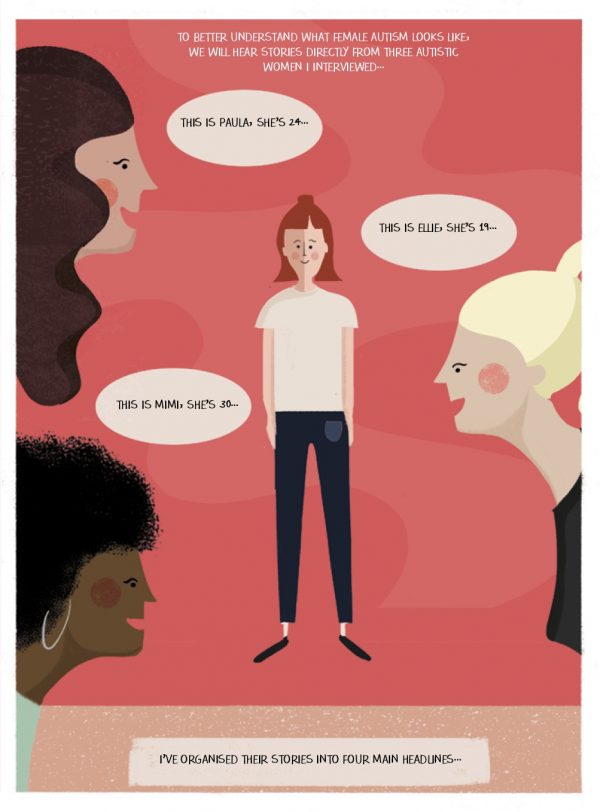

Like any comic that portrays people’s actual lives, Bargiela has sought out real women to talk about their experience with autism, specifically the obstructions to diagnosis and what getting what meant to them, especially in the context of the ways they learned to cope before ever getting confirmation.

The stories are drawn together through certain consistent aspects of an autistic woman’s experience, like family dynamics, school experience, and the women telling their versions of these. These individual stories are united by one important conclusion — how exhausting it is for people with autism to function in what many of us consider normal situations. In my experience that’s one of the hardest things for those of us on the outside to truly understand, as we are fooled that if a person with autism seems to be functioning in a situation, then they are handling it as we would, and so if they register the stress they are feeling, sometimes the non-autistic person finds it off-putting. This seems consistent with all the testimonies in this book, and it’s something that friends and loved ones of people with autism need to hear and understand — just negotiating moments with YOU might be exhausting for this person you love.

It also goes into detail the difficulties they had as girls in relationships, trying to understand what was expected of them as a “girlfriend” and how to navigate intimate feelings when you can’t read other people very well and don’t have a sense in social terms what such a relationship even means. This seems to be an area that any person with autism should be consciously prepared for, but girls in particular, as what we see as the natural dynamic between teens often sets-up girls with autism as victims of abuse, and the book gives solid information in regard to these issues, including the pressure to even have a romantic relationship.

The book finishes with an examination of the conflict between interests as a way of bonding and making friends and the autistic prevalence for obsessive interests that can obstruct the effort to make friends. It’s not a how-to make friends section, but rather a reassurance of the idea that interest may have more to do with identity for a person with autism than relationships, and that’s okay — the idea might be to realign expectations and create comfort with what is natural rather than demand replication of the “accepted” dynamics of friendship.

Sophie Standing’s artwork is a big strong point in the book since she has to walk a delicate balance in presenting the information as friendly and engaging, and giving it personality while still maintaining a level of universality. She also has to move between informational parts and depictions of personal lives that give you something to cling onto emotionally. She does this perfectly, employing a playful flat illustrative style that’s graphically sophisticated but also suited to depicting emotional scenes well.

This is a really lovely book that manages to speak to several audiences at once in an accepting way. It covers the girl’s perceptions of gender differences in regard to autism, and also how they perceive gender difference in those who don’t have autism but also offers research in that area. And regardless, I think this is a great book for boys and men to read as well, particularly those on the autism spectrum. It may help them find greater understanding, and perhaps they might see something of themselves in either the behavior or the personal stories.

If you know a girl or woman with autism, or who are exploring the possibility that they have autism, or maybe even a parent with a child in one of those situations, I highly recommend this book. The way the information and research are gendered means that a gift like this could make a significant difference in someone’s life.

Where’s the mention of if you ARE a woman with autism? Please don’t leave us out

Comments are closed.