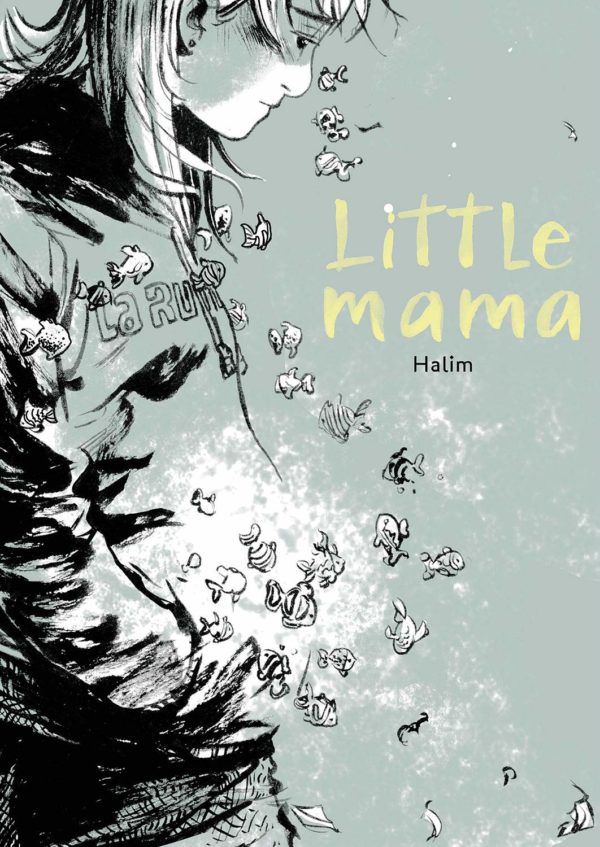

Little Mama

By Halim Mahmouidi

Lion Forge

[Disclaimer: Lion Forge is a sister company of Syndicated Comics, which publishes The Beat.]

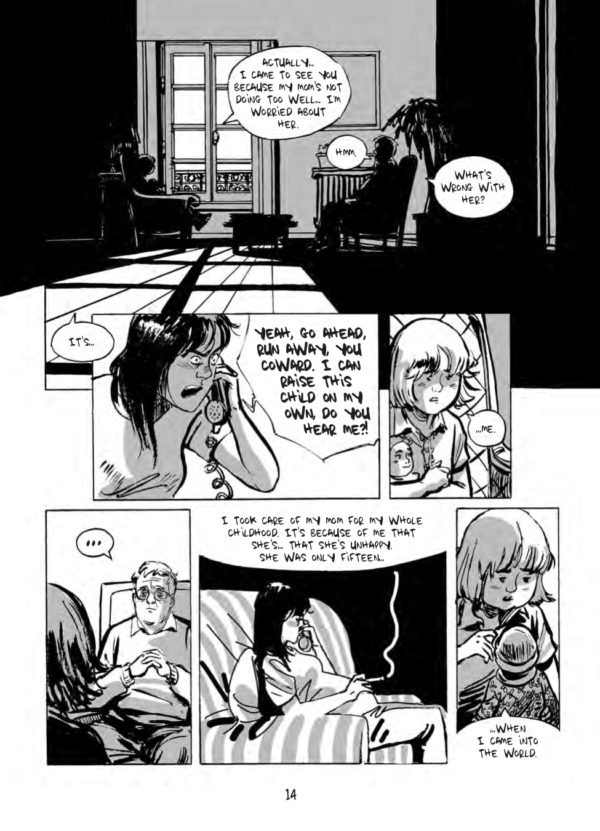

Is there another graphic novel as uncomfortable to read as Little Mama? Probably so, but one doesn’t currently come to mind, and that’s probably my brain going into self-defense mode. At its core, Little Mama a story about a girl named Brenda, recounting her life to a therapist. When she walks into his office, she is just a little girl, though she claims to be 29, and begins to talk about her mother’s troubled time raising a child as a single mother at 15. As the circumstances of Brenda’s life unfolds, we see the real woman behind the child who entered the office.

It begins as I imagine quite a few stories of child abuse begin, with sleeplessness on the parent’s part, aided by a lack of support and exacerbated by the seemingly endless and incomprehensible demands of the baby. It starts with a show of seriousness like a strong tap to the baby, then another one, and somewhere in the haze of perception of the desperate parent, that becomes the normal procedure for handling the situation.

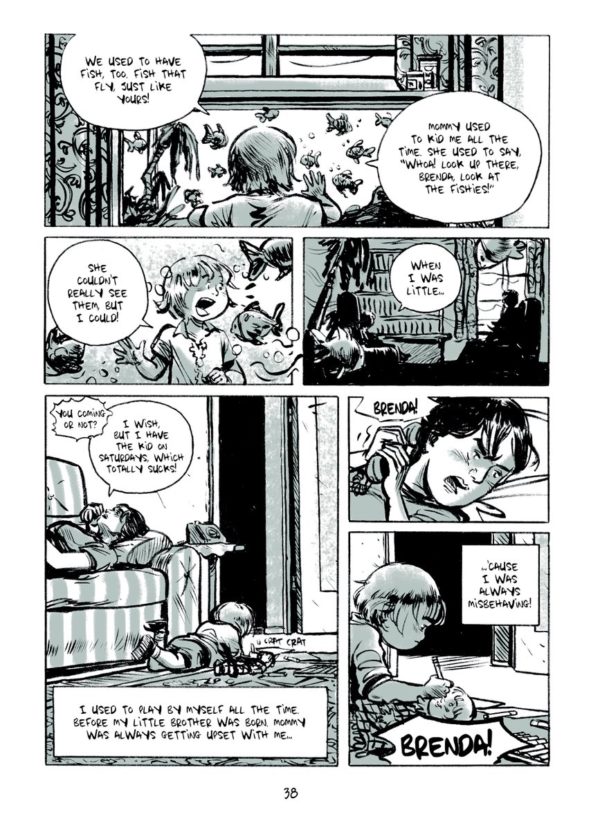

Brenda’s life of abuse coasts from there. Slaps, hits, pinches, these become the conversation between she and her mother as she gets older, and Brenda is made complicit in her own abuse by being expected to remain silent about it. She’s also given the nickname “Little Mama.” She’s called that because she is placed in the adult role with her mother, taking care of her throughout her self-destruction. It’s one of the worst things psychologically you could do to your kid, pummel the lines between parent and child, heap onto the child the concerns and secrets of the adults. These are burdens Brenda has to drag along with her through life.

It’s the arrival of a boyfriend where things get worse and the steady stream of expected abuse escalates into terror and torture.

The main character in Little Mama is an intangible force that has far too much presence in the world — brutality. This is typically the result of rage or disassociation, two states of human emotion that seem to walk hand in hand and can be reactions to situations not going as you need them to be. Rage is the frustration part that leads to the brutality, while disassociation is where you give yourself permission to act brutally. It’s played out in systematic terms in history, but also in personal lives for just as long. It’s that moment when you need something to do what you want it to do and you decide it is not human, that it must be forced to submit. You opt for violence that goes far beyond a momentary loss of control. You decide to punish.

Halim Mahmouidi’s story unfolds through Brenda’s monologue, and it is literally a laundry list of atrocities unleashed on Brenda, as she recounts her life in an attempt to come to terms with the repeated traumas of her childhood. The story is a little old fashioned in this way, as Brenda is reassured by a kindly old therapist who looks the part of a loving grandpa as he passes along sage nuggets of self-analysis for her to use in getting to the core of her pain and unleashing the strong woman she’s become.

But Mahmouidi’s raw illustrations depict Brenda’s story with a jarring emotional intensity that surpasses the story. The violence bursts from the page in emotional terms and as the rage builds, overtakes even the layouts, threatening to make even the basic principles of visual storytelling crumble in its wake. As unpleasant as some of this is to read, it’s also what makes the book come alive, providing the reader with their own visceral experience that allows them to feel Brenda’s terror.

If nothing else, this is an antidote for disassociation — seeing things from the eyes of a victim is a step in preventing brutality, and the world could certainly use less of that. It doesn’t make for a pleasant read, but it does make for skilled advocacy in defense of victims.