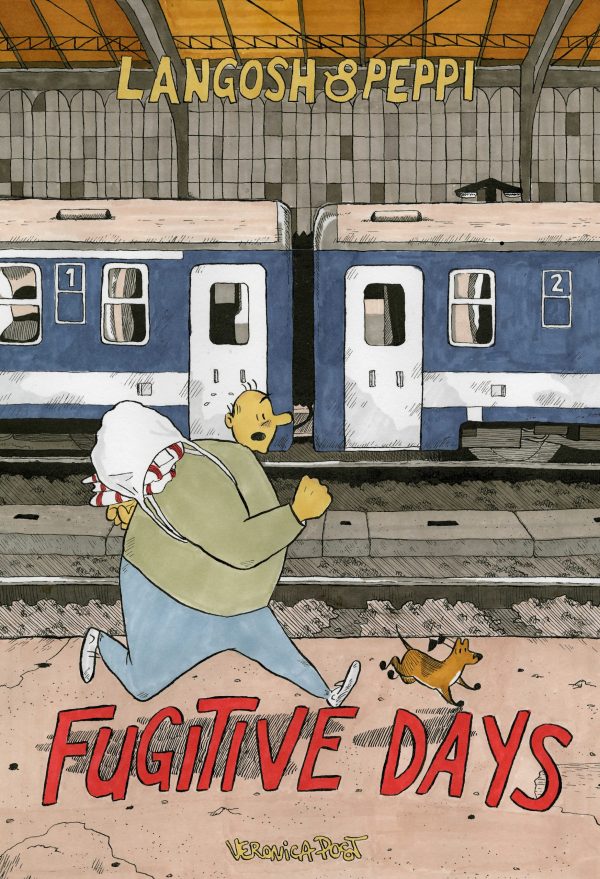

Langosh and Peppi: Fugitive Days

By Veronica Post

Conundrum Press

There’s an allure to former Iron Curtain countries that is hard to put into words, but it has something to do with their strange existence as old cultures inside interrupted countries, constantly the victim of oppressive outside forces that have forced the people to quickly adapt while doing what they can to hold onto who they are and what came before them. It creates some unusual landscapes and atmospheres, and the continual struggle of attempting to find themselves amidst the prospect of falling back into self-destructive Soviet ways manifests in something intense, dark, but also prone to catharsis.

I was excited to read Veronica Post’s debut graphic novel Langosh and Peppi: Fugitive Days because I had visited Budapest near the time she places her story, a work of fiction that wraps in many aspects of her actual time in the city. In fact, she captures a lot of what I saw and felt there, including the feel of being an outsider in a place that was challenging me to go deep within it all the while being so completely alien that if you even stumble upon an entry to its mysteries, what you find inside might confound you.

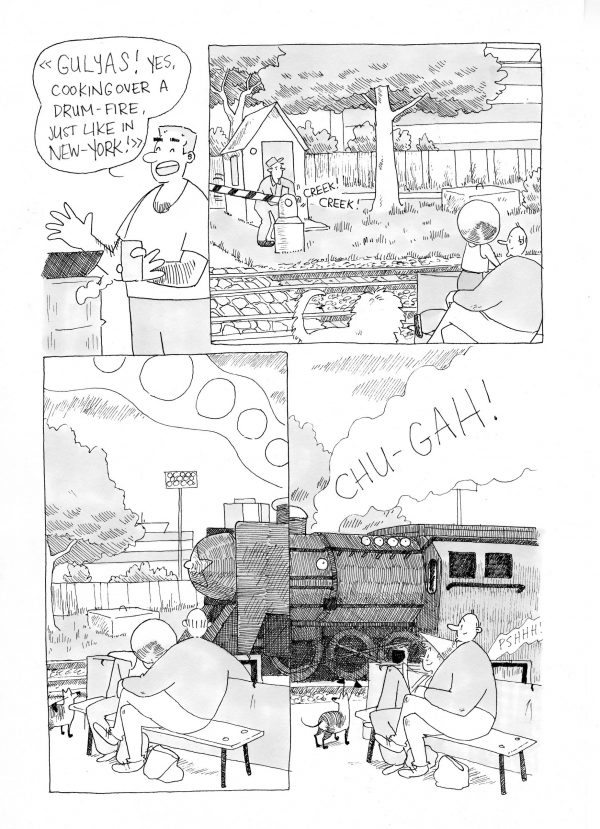

Langosh is a fugitive from Canadian justice because of some smalltime offenses who fled overseas and found a place to harbor him in Hungary. He and his dog Peppi bum around Budapest a lot, meeting up with his energetic and exhausting friend Yeva on occasion and finding places to squat. As the book starts, Langosh has to cross the border to get his passport stamped, and so he flees to Croatia and Sarajevo, where he fumbles around, explores strange monuments to past paranoia in the form of abandoned underground bunkers, and travels in fear of his status as a fugitive being discovered.

After he returns to Hungary, he heads for the countryside with Yeva to stay in one of her friends’ homes but finds the placid natural world to be just as filled with strangeness and foreboding as anywhere else, particularly in the realm of abandoned bunkers, but also hostile and curious neighbors who take part in clandestine and suspicious activities that raise alarms for Langosh and hint at the small-time criminal endeavors that created strange webs through the post-Soviet world.

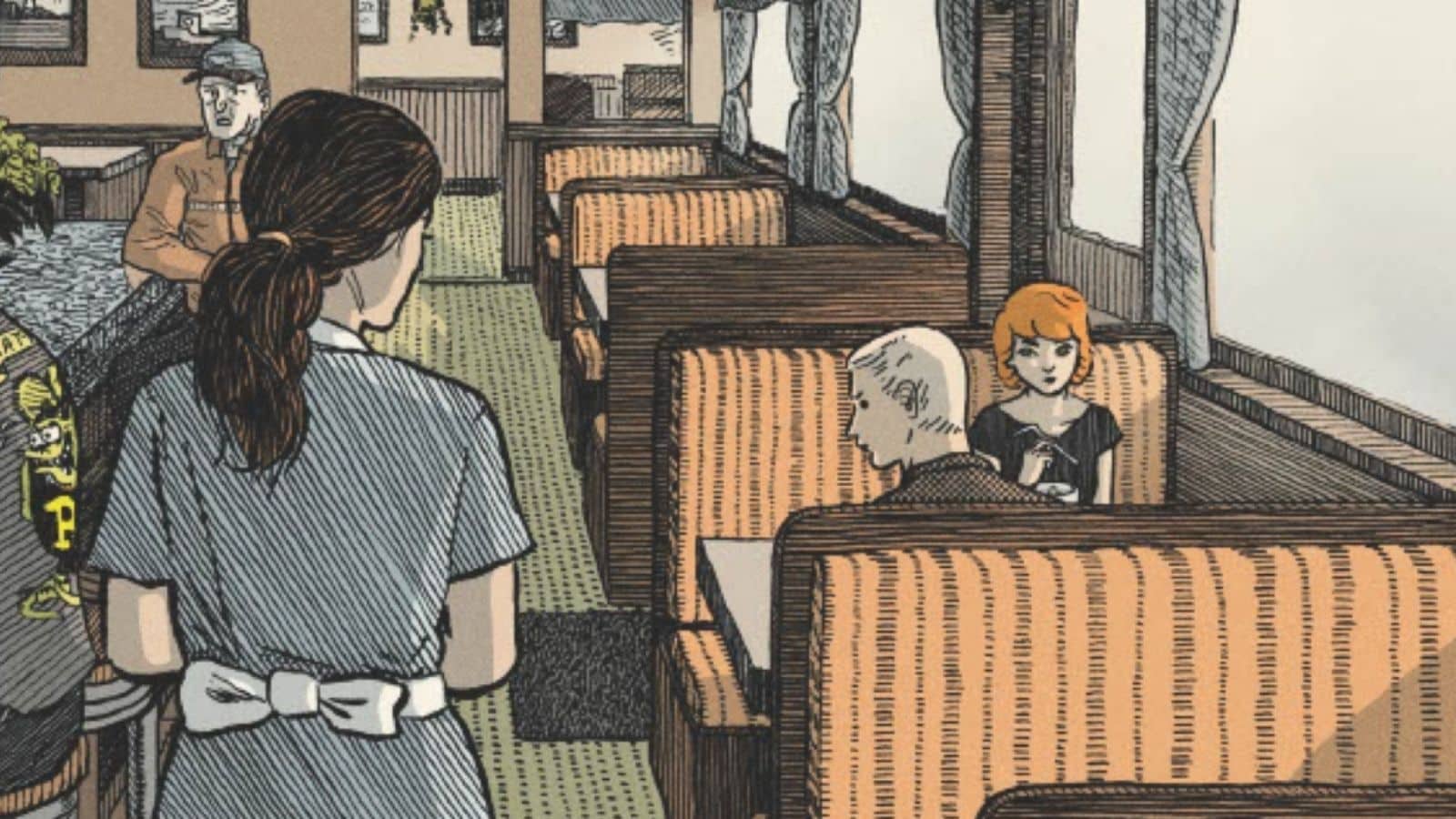

The book finishes with Langosh’s return to Budapest and the chaotic influx of refugees trying to make their way to German, but being stalled in the Hungarian city and taken advantage of by citizens there as well as police.

It’s an odd but effective build-up that Post gives Langosh and Peppi: Fugitive Days. At first, it’s very casual, with Langosh and his dog wandering aimlessly and happening upon interesting things. The pace of the story is dictated by the pace of his daily life. But as he continues to try and make his way, his efforts become more and more distressed. As the book began, Langosh really was a traveler passing through places, soaking up any charm and bizarreness on offer, but the longer he sticks around, the longer he starts to pierce the ugly aspects that a tourist might never encounter.

But it’s really alongside the refugees that Langosh begins to buckle under the weight of Hungary and the other countries have been showing him. These are places that wear their wounded history on their sleeves, unlike the west with long-established cultural processes that sweep everything under the societal rug. In Eastern Europe, it’s all raw, and that might be for the best — unlike in the United States, it doesn’t creep up on you, shattering an agreed-upon illusion. In Eastern Europe, it’s just part of a cynical view of reality that comes from the region’s history.

Post’s art is mostly uncluttered and breezy, and this does well in portraying the personal aspects of the story. But the landscape is a character as well, and she doesn’t skimp on its presence, adapting the intangible moods and physical intricacies into a style that doesn’t overtake what she establishes for her characters. That actually gives it the feeling of being another world entirely, which serves the mood of Langosh’s experience well. Something is off-kilter and not negotiable by the tools we bring to it — a foreign land presented as foreign and like Langosh, we can walk inside it, but not necessarily actually be a part of it.