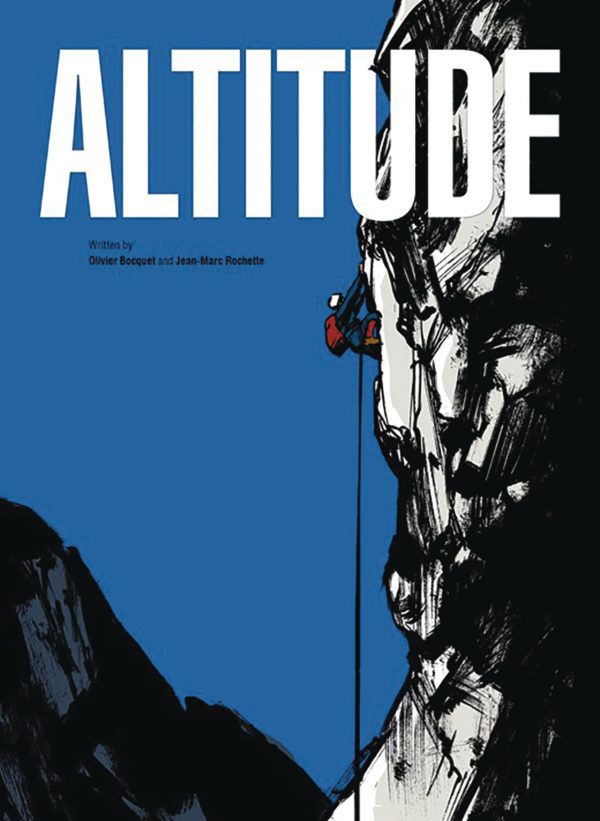

Altitude

Written by Olivier Bocquet

Written and Illustrated by Jean-Marc Rochette

Translated by Edward Gauvin

SelfMadeHero

I was recently standing at a local landmark called Witt’s Ledge, the cliff atop a former quarry looking down 1100 feet and thinking what a nightmare it would be to climb. Down below, it looked even worse. That’s with the knowledge that people have used it to train for rock climbing and once in the 1970s, someone did fall off the top of it and instantly died.

I immediately thought about that while reading Altitude, the memoir of artist Jean-Marc Rochette, in collaboration with writer Olivier Bocquet (the team behind Snow Piercer), about his younger years climbing rocks much taller than 1100 feet and rendering these feats with a remarkable ability to inspire terror at dangers inherent and admiration at the bravery or the foolishness involved.

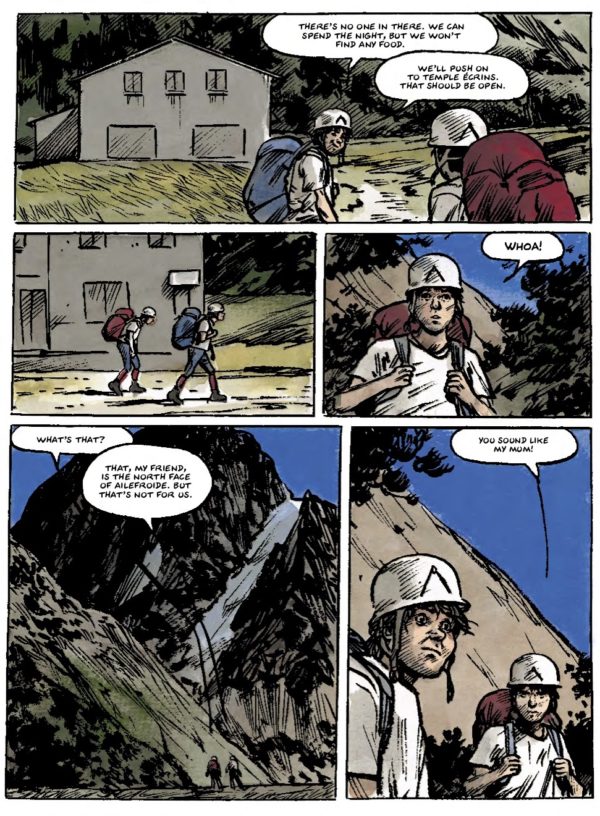

Rochette is a troubled kid, his mother a widow and having a hard time getting a handle on him. His desire is to skip school and go climbing after being tempted by his friend Sempe to make an attempt. Sempe is a demanding teacher but Rochette soon becomes his equal, and the towering peaks transform into the landscape of their coming of age as they struggle with romance, independence, and responsibility. Climbing becomes a form of rebellion, especially for Rochette, who moves well beyond his friend and teacher, taking on bigger challenges and higher risks as he moves forward in his life.

But there’s an aspect to Rochette’s efforts that seem like he’s trying to escape something, and there’s no elevation that can bring him as far away from his ghosts as he needs to be. Rochette requires something else with the climbing, somewhere to put his wounds and burdens and express himself to other people, and that grows alongside his climbing in the form of creating comics.

Rochette’s narrative winds around several intentions as it moves along. One part is very firmly in the young person growing up narrative form, capturing all the snotty haughtiness of young guys and the peril they put themselves at as they grapple to figure out who they are.

But there is also an aspect of instruction that gives great detail about the mechanics of mountain climbing and the history of the best of those who have embraced it. These parts could feel like intrusions in certain depictions, but there they give context to a world that the reader might not be a part of and make clear the details of the process that Rochette puts himself through, so we get a better understanding of not only the danger but the skill.

It’s Rochette’s experience with climbing that makes Altitude so successful since he is able to put into visual terms to the danger and skill that is explained. The sequences of climbing feel especially harrowing for a comic, with a lot of fascinating detail to the intricacies of the rocks being climb and adding some perceptual drama that comes from being a climber. The body language of he and his climbing partners and the personality of the mountains and cliffs and caverns and crevasses become as much a part of the autobiographical narrative as any of the words or facial expressions during character conversations.

I didn’t enter into Altitude with much of an interest in climbing, but Rochette’s presentation drew me in and gave me a huge appreciation of it — and vice versa, in that gaining an appreciation of it magnified my interest in his story and the traumas that ensue.