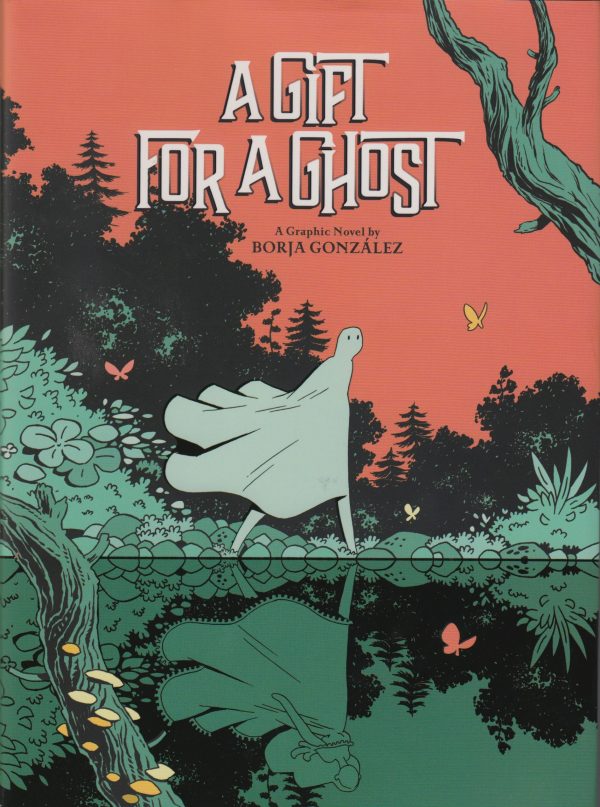

A Gift For A Ghost

By Borja Gonzalez

Translated by Lee Douglas

Abrams

From the moment I finished A Gift For A Ghost I knew it was different from most other graphic novels I read for one simple reason — I immediately went back and reread it. That’s the kind of mystery that Spanish cartoonist Borja Gonzalez’s first book-sized comics work inspires. Not mystery as in something that is solved upon a second reason, but rather one that embraces its implications without making a final revelation necessary to enjoying it. Revelations maybe, but never final.

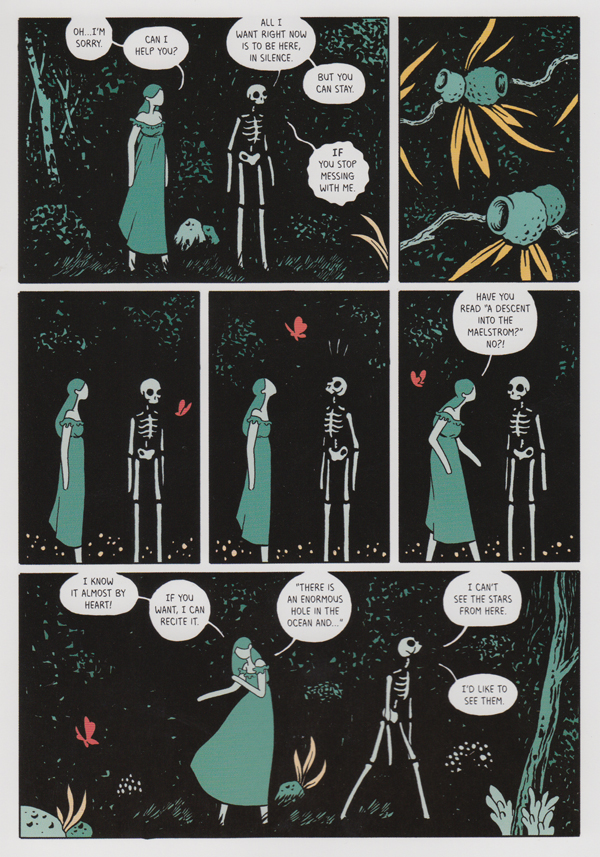

A Gift For A Ghost follows two narrative paths. In 1856, Teresa stymies her family with her obsession with unexplained weirdness and her insistence on writing poetry about her thoughts and her encounters with strange things. When we first meet her, she’s out in the woods at night encountering an extremely strange thing, a skeleton that is not dead and that feels a consuming sadness that sends it seeking solace in the night sky.

In 2016, Gloria is meeting up with Laura after listening to Laura’s band’s demo tape and agreeing to meet the other member, Christina, in order to decide whether to join the band or not. Gloria admits she has no musical ability, but that’s viewed as a strength by the other two. The band’s real secret weapon is Laura, though, whose lyrics Christina describes as “the Bronte Sisters giving a talk about the study on the thermonuclear fusion of stars,” which Christina also believes will change the world once they are unleashed in musical form.

After establishing the two time periods and creating thematic links between the characters, Gonzalez steps back from forming any obvious linear ones that will transform into a standard time travel plot and instead takes a more poetic and elusive approach to examining the dynamic between the band members in 2016 and Teresa and her sisters in 1856. Teresa is at odds with her younger sister, who spies on her and threatens to be a snitch, and also her older sisters, who reject and ridicule her interests and talents. This causes her to dig in further regarding the expression of her experience and taunting her younger sister with it, making the difference she feels from the rest of her family into more of a defiance designed to accentuate her self-identity. With the band, it becomes more complicated, as Laura’s eccentricities also highlight differences, in this case with her bandmates, and also hint that she’s holding something inside her that she feels uneasy about sharing.

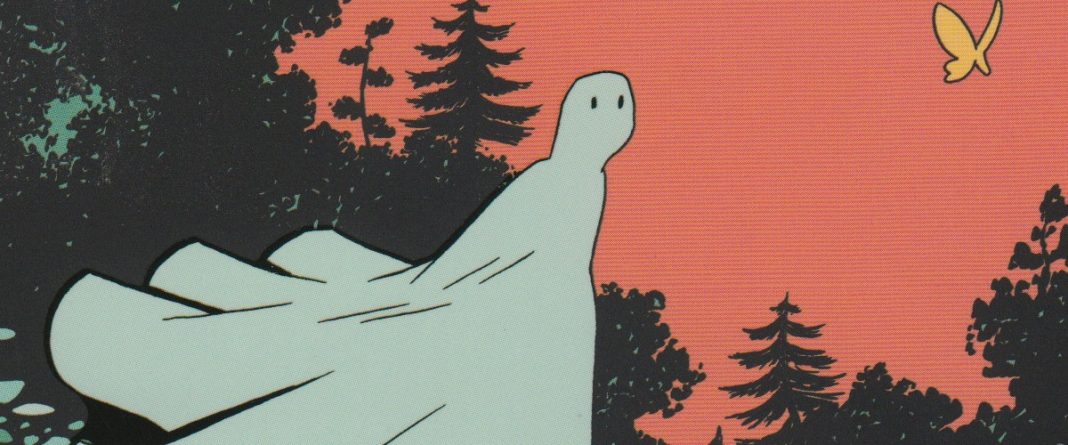

As Gonzalez portrays two eras of female defiance towards the norms of the times and the accompanying embrace of the weird and the dark, he does so with incredibly beautiful illustration. On one hand, his figures are simple though animated, with blank faces and personalities that spring forth through body language. Often existing the dark, Gonzalez uses illumination to create some more complicated surroundings, or at least imply intricacy beyond the characters’ perceptions. Filled with green washes and shadows, with other colors like red invading the panels in quiet ways, and then on certain occasions overtaking everything, Gonzalez matches the tone of the story perfectly with his artwork, fashioning an otherworldly reality for his characters to play out their roles within, one in which the very palette directs an evasive and foreboding atmosphere that dominates their actions.

I don’t do this often, but I looked around online for other people’s reactions to A Gift For A Ghost and I was disappointed by what I found, though it clarifies something I’ve noticed about the way modern audiences take in certain kinds of stories, especially younger audiences. There seems to me to have been a mass exodus from works that favor abstract interpretation over clear plot reasoning. Much of the complaints I saw about the book was that it didn’t spell out the connections between the different times in the book, which made me sad. It was as if the readers were incapable of approaching it on a conceptual level, that they required a what-you-see-is-what-you-get realization through straightforward plotting instead of the poetic work Gonzalez gave us.

A Gift For A Ghost is the exact opposite of the way so many stories are told today, and that’s what made it such a pleasure for me. It didn’t tell me anything. It assumed I can think abstractly, that I can understand that what is on the page (or the screen in other works) is not the only thing that I’m supposed to see or feel about the work. It’s not just about telling what this character did when and where, but about making creative, philosophical, emotional, and thematic connections that link the two time periods and the characters in them.

It’s about collaboration between the reader and the work and creating a personal experience from it, something that all the best creative works aspire to.