My first encounter with Howard Cruse had nothing to do with comics. At the time, in 2005, I was a reporter for the North Adams Transcript and Howard was a new resident. He and his husband Ed Sedarbaum had started hosting Sunday morning gatherings that they called the “Potluck for the Creatively Afflicted” and since I knew who Howard was — mostly by reputation — I thought the event would make an interesting newspaper story. As it turned out, Howard and I just got along well. Years later, I’ve come to see that this is just what happened with Howard. He met people in a variety of ways and instantly made friends with them.

Even in an area dominated by visual artists, I wasn’t always sure that people in the Berkshires really understood who Howard was and what he had achieved in his career as a cartoonist, so I made it my mission to get his personal story and work out there in the local newspaper on a consistent basis. But Howard didn’t really need my help because his personality won him many friends and much respect. He was a gentleman to his core and this served him well in connecting with other people, most of whom had little to no clue about his role as a pioneer of queer comics and his contribution to the must-read canon of graphic novels. They just knew him as a nice guy.

And so while I was educated on Howard’s wider contributions to the world, it was on a local level that I knew him most intimately, and I’m here to tell you that what was contained in his comics work came out just as vividly in his personal interactions and his approach to community. He lived what he portrayed.

Following the news of his death, my Facebook feed filled up with posts and comments from local people giving testimony to Howard’s kindness and welcoming nature, telling stories not of his cartooning, but his genial spirit and the way he greeted newcomers in the area with warmth in order to make them feel at home, and how he reached out to younger cartoonists and artists, eager to support them, learn more about them, and in the case of many, help them feel less alone in the universe.

A perfect example of this is from Seth Brown, a writer and comedian who lives here in North Adams. He captured the Howard that many of us know with what he wrote on Facebook, and he’s letting me share his words with the comics community at large:

| “Whenever people ask me why I stayed in North Adams, I say it’s because of the local arts community. And if one man exemplified and brought together the local arts community I so valued in the decade after I moved to town, it was Howard Cruse. I didn’t know many people in town when I moved here but was invited to a ‘Potluck for the Creatively Afflicted’ that he and his husband Eddie were kind enough to host. They were always incredibly welcoming, and it is through those monthly potlucks that I first began to feel like I actually belonged in North Adams. It was only later that I would learn that Howard was an internationally-renowned award-winning graphic novelist, but you would never know he was famous from the quiet, unassuming, and incredibly kind manner in which he interacted with everyone.” |

In an interview I did with him in 2007, Howard expressed that he made lemonade out of lemons in his career path, though acknowledged the bits of lemon that stuck around. “I never

For me personally, Howard was a vigorous supporter of my newspaper writing, of political opinions I expressed in my columns, and of my efforts to write about comics in a daily newspaper setting alongside contemporary museum art. He was like that for a lot of creative people around here, though. Howard was one of those reliable friends who showed up, whether it was making sure you knew that he appreciated your work or coming to your gallery openings or whatever that meant.

Howard was often asked whether he would ever do another graphic novel. That was never going to happen — it was grueling work that became more difficult as he aged and he felt that with Stuck Rubber Baby he had given the world the best comics version of him and he was very right. He told me, “I have mixed feelings about the labor intensiveness of the graphic novel form. It’s really, really hard work and as you get older, chopping off five years of your life becomes a bigger proportion of what you can reasonably expect to have left.”

What Howard could “reasonably expect to have left” was filled with pursuits locally. I don’t think he needed another graphic novel to make his mark on the world.

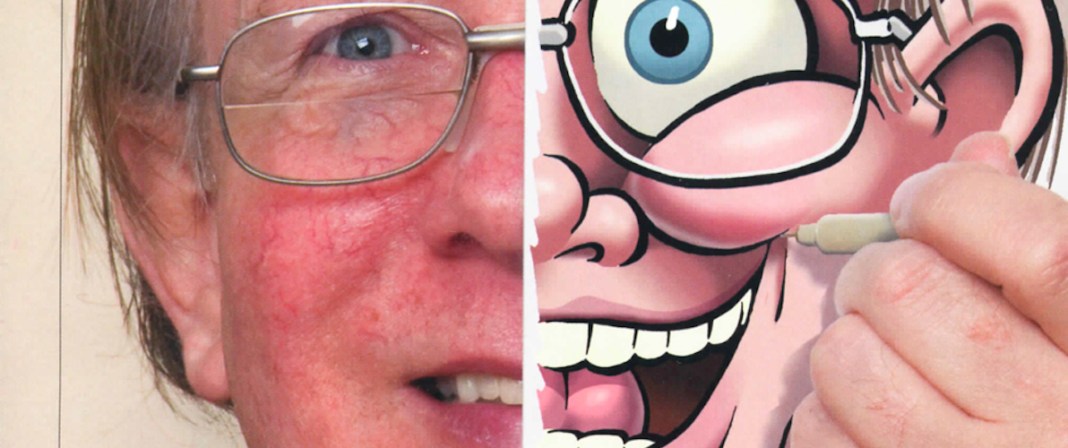

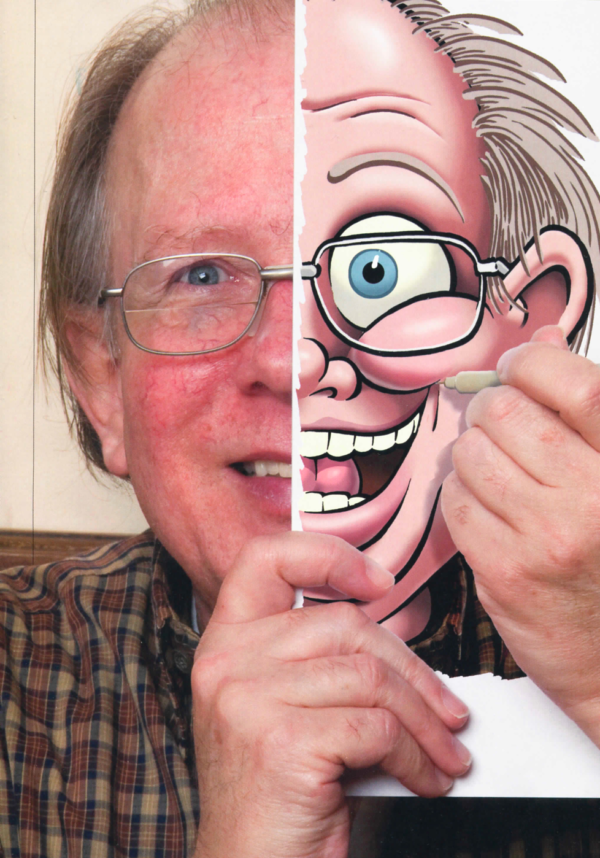

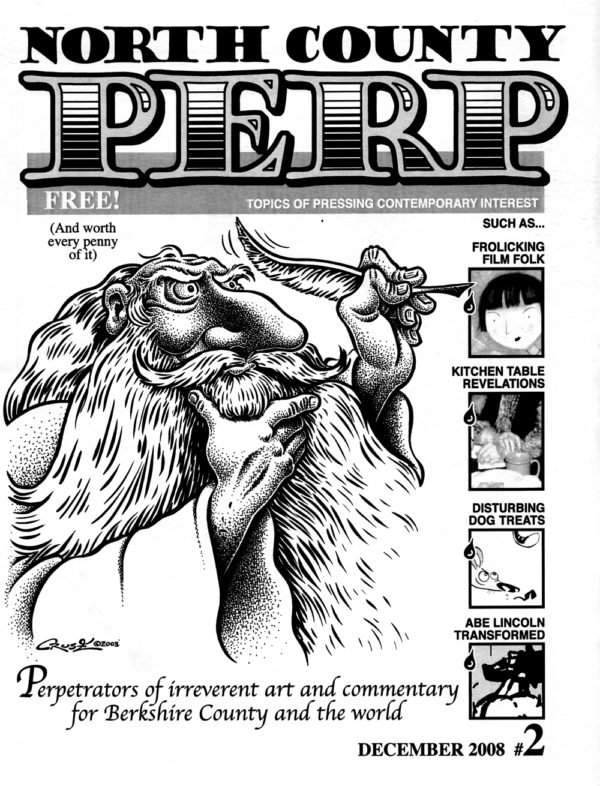

For a while, Howard taught cartooning in the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts’ fine art program here in North Adams. He published a two-issue zine called the North County Perp, which Howard edited. It gathered area creative people to contribute stories, poetry, and, of course, cartoons, some of them even by Howard. I had a short story in the second issue which Howard edited. He created artwork for the drama team at the local high school. I ran some of his political cartoons in the newspaper. Howard’s artwork was featured in gallery shows of local artists and a group show of cartoonists at the Norman Rockwell Museum, as well as one in a local gallery celebrating underground cartoons.

He was an active member of Rainbow Seniors of the Berkshires, which was started by his husband Eddie. He gave readings at local bookstores with other area writers. He could be spotted at political marches and protests in the area as well as Pride gatherings and parades. He took part in theater productions here, too. He loved community theater. That was one of his great passions.

His love of comics and his perspective on life as a gay man were topics of conversation with him during an evening of hanging out, but they were accompanied by hilarious and quirky stories of his childhood as a minister’s son in Birmingham, Alabama, which might touch on his enthusiasm for ventriloquist dolls or the comics he created as a kid, as well as tales of his father’s job. He expressed these memories with self-deprecating charm.

And, of course, politics came up, as well as his life in the gay counterculture of 1970s New York. How this polite, soft-spoken guy was an active part of that scene has always amazed me, but Howard was quick to point out the difference between “radical appearance and interior individualism.” He said that taking art seriously as a professional pursuit made the visual affectations of the counter culture “distractions,” and said he felt set apart from some of the other radical cartoonists because he did respect tradition.

“The person I am today who visually doesn’t come across to be any kind of radical – and I was raised to be a nice polite boy – hasn’t given up any of my beliefs that sex should be totally integrated into the realm of topics that are covered without embarrassment,” he told me.

Given those views, it wasn’t a surprise to me that they manifested in terms of Howard being a homebody through and through. He seemed a little embarrassed to be honored in Europe, and just as hesitant to be flown out there to receive the accolades personally. He told me that traveling like that just wasn’t his thing. But making himself the center of things and attempting to seize the attention of others seemed generally not his thing as well. It was only the afternoon following his passing that I even found out that he had a Patreon account that he seemed to regularly maintain. He never told me. In fact, he didn’t seem to tell anyone I’ve asked around here. He wasn’t braggy. Self-promotion just wasn’t in his DNA.

Even still, he was thrilled when his personal archives were acquired by Columbia University Libraries’ Rare Book & Manuscript Library. That really meant a lot to him, but of course, when he told me about it it was with the same amused, self-deprecating way that he would anything else.

Howard was the type of person you were better off for knowing. The comics he created were true expressions of what was deep in his soul, and in this era of terrible, shallow behavior that directs hurt from one human to another on a routine basis, it is clear to me that the world requires more people like Howard Cruse. However, it’s also clear to me that just one Howard Cruse made an enormous amount of difference with numerous people from many parts of society. And that’s why I’m going to miss him.