Welcome to Minis of X, a new feature within our Heroes of X/History of X X-Men column that X-amines the miniseries of the X Universe! While I was working my way through X-Men Omnibuses (Omnibi?), I realized it was difficult to fit miniseries into my coverage of the larger X-story arcs, so rather than omit them entirely, or force them into already significantly long columns, I thought “what the Limbo?”, let’s just create a new feature that gives the minis their due. This first entry covers Wolverine (1982) by Chris Claremont and Frank Miller. This series is sold in trade paperback and hardcover as well as included in Uncanny X-Men Omnibus Volume 3. To read my coverage of the main stories in that omni, check out the last entry in History of X.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Wolverine (1982)

After a couple of previous adventures in the “Japan” of the Marvel Universe (note the scare quotes since it has very little to do with the real Japan), Logan returns to the island nation when he realizes all of the letters he has sent to his long-distance-bub-boo Mariko Yashida have been returned unopened! Claremont puts on his Dashiell Hammett hat for this series and Frank Miller creates some of his moodiest visuals ever for Wolverine Does “Japan!”

The first Wolverine mini would become a cornerstone in the mythology of the mutant and his characterization during these 4-issues has stuck with him for 40+ years. Is it must-read comics? Honestly, I really think so. In order to understand the rise of this scrappy lil’ canuck to the monolithic intellectual property he is today it’s important to read the story that made him a leading man. While this series is great comics in the eyes of many readers, it’s also necessary to note that it is often very problematic and includes racist stereotypes and a fair amount of misogyny.

Your mileage may vary, the issues with this series could turn you away and that would be understandable. I think there is a lot to enjoy here but the problems should not be overlooked. Luckily you can skip it if you find the content too cringy for your taste level, nothing that happens in this series or in Wolverine’s subsequent adventures in Madripoor is required reading for the casual X-Men fan. Many readers try their best to ignore Logan’s exploits as much as they can. I recommend giving it a try and deciding how you feel but at the end of the day, just read the stuff you enjoy. WHEW. Okay, let’s snikt in.

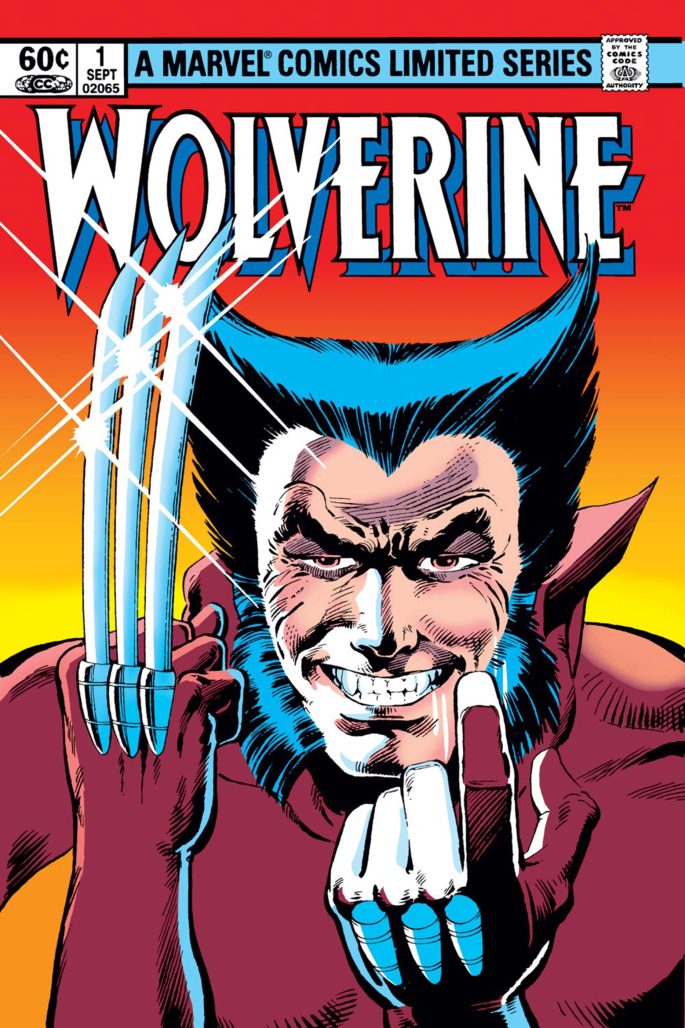

We first see Logan grimacing in a full unmasked splash page close-up. His widow’s peak is as angular and sharp as his arched eyebrows turning his forehead into a mountainous landscape of “manhood.” Wolverine is sharp, wolverine is hairy. On this first page, Wolverine introduces himself through captions, reveling in the noir of it all, and treating the reader to the oft misquoted catchphrase “I’m the best there is at what I do. But what I do best isn’t very nice.” The narration in this series is first-person present tense, a classic Noir style that will become a hallmark of Wolverine-centric stories. This isn’t the first time we’ve seen Claremont write Wolverine’s internal monologue in this way but it’s refined in this series to its purest form.

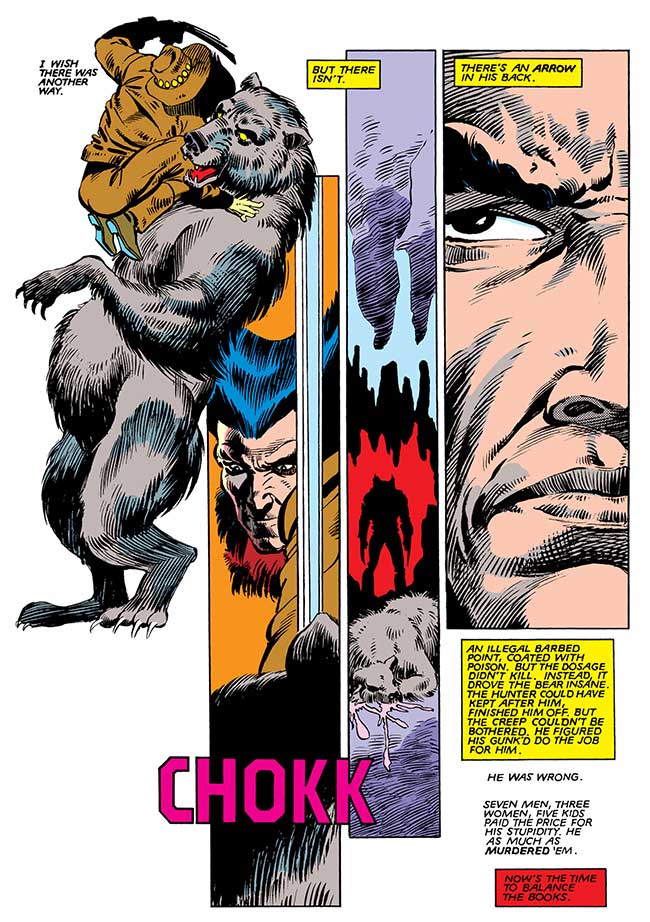

The cold open is a bear hunt, Logan narrating and waxing morose about his murderous nature the whole way as he pursues a Grizzly gone mad with berserker rage. Wolverine is violent, Wolverine is hairy. After dispatching the monstrous creature with relative ease, thanks to his adamantium skeleton that he explains internally to himself in detail for some reason, Logan confronts the hunter who carelessly left the bear alive after wounding it with a poison-tipped arrow.

Clearly, Wolverine and this bear-gone-wild are mirrors of each other. Claremont and many other writers will use this reflective relationship over and over to address the man/beast dichotomy of Logan’s character. This intro establishes that while violent, brutal, vicious, and bear-like, Logan is a man with a moral code, a man of integrity, and a man of “honor.” Spoiler Alert: We will never stop hearing about Logan’s “honor.”

After this opening salvo, it’s off to Japan to find out why his fair lady Mariko ain’t been readin’ the letters he’s been sendin’! Wolverine is a very specific kind of male character. He’s the bastard child of Clint Eastwood, Jack Palance, and Jack Nicholson. In Logan, Claremont engages in all of his most puerile white male wish-fulfillment fantasies and the result is a walking talking snikting wad of testosterone. Wolverine is so butch it’s camp.

In early Claremont issues, Wolverine repeatedly refers to women, like Mariko, as “frails,” a hilariously misogynistic and demeaning term based on rhyming slang (frail frame rhymes with dame) popularized in the underworld circles of the 1940s and noir fiction. Where some heroes fly or shoot concussive beams from their eyes, Wolverine is superhumanly “masculine” and traffics in a very insistent and aggressive form of white male exceptionalism. He’s honestly not dissimilar to Roadhouse protagonist James Dalton in this clip here. “Pain don’t hurt” and all that jazz.

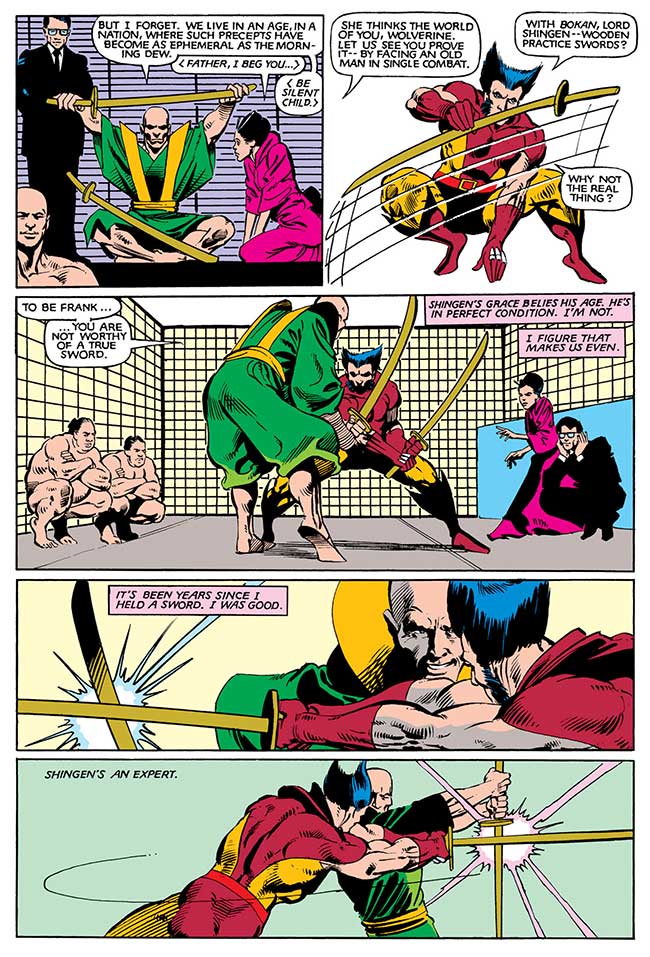

Soon after deplaning from flight 007 (Jesus, Claremont), Logan is detained for a brief moody penthouse meeting with one of Japan’s “top people” Asano Kimura. Two panels into this section and Claremont writes Kimura saying Logan is “more truly Japanese than any other Westerner I have ever known,” a refrain that will be repeated in some form throughout this series.

Claremont clearly fetishizes Asian cultures and the level of respect varies between stories. In this mini-series, both he and co-writer/artist Frank Miller are obviously fascinated with what they believe Japanese culture to be. Despite perhaps beginning from a point of admiration, Claremont and Miller aren’t particularly concerned with accuracy. The Japan of this series (and many future Marvel stories) is a largely stereotypical and tropey approximation of the country cobbled together from martial arts films and exploitative pulp novels.

In his essay, The Whitest There Is At What I Do from the collection Unstable Masks: Whiteness and American Superhero Comics (which you can read here) essayist Eric Sobel writes that Wolverine, “A hero armed with the privilege and invisibility whiteness affords…unlike the foreign characters he encounters, is able to easily move between different identities without placing his whiteness and the agency it bestows in any real jeopardy.” (You can read more excellent analyses about Claremont’s X-Men and Sobel’s essay on The Claremont Run’s Twitter linked right here.)

Wolverine is characterized over his full publication history as being the best there is at all of the things a young boy might want to be the best at. He’s not only the “best” samurai, but also the most rugged cowboy, the most decorated GI, the most honorable fighter, the most skilled lover, and the most all-around stand-up “guy” that people, especially young boys, love to root for. Hell, Wolverine has retconned his way into every major historical event, real and fictionalized, of the past 150 years. Wolverine threw the first brick at Stonewall! (Not really, but I’m begging a writer to have Marsha P Johnson “fastball special” Wolverine through a plate glass window.)

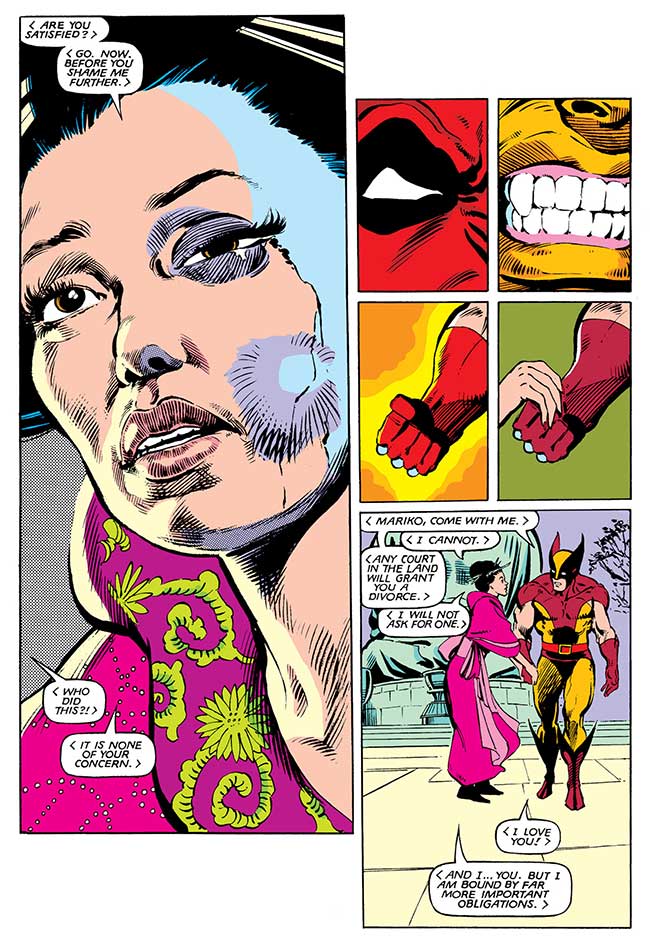

Back to the series, the women in these comics are opposite extremes of reductive Asian fetishization. Mariko is honor-bound and reserved, engaging in the “geisha” stereotype. At every turn, her agency is stripped and she is objectified by every man in her life including Logan. Logan’s desire and “love” for her are clearly meant to read as “true” and “pure” but come across as possessive and often very scary. Yukio, introduced at the end of the first issue, is a version of the “sexy ninja assassin” character common in genre fiction mixed with the even more unfortunate “dragon lady” trope. Neither woman gets to have the fullness of character that Logan does, Mariko fairing worse perhaps than Yukio.

When a dishonored and beaten Logan twice fails to excise Mariko from her father and her abusive husband’s clutches, he’s taken in by Yukio, a wilder woman who engages in his more base yearnings for violence and risk. By the third issue in the series, Logan is a drunken mess who has seemingly abandoned his obligations to the X-Men for months in favor of playing chicken with bullet trains and dreaming himself into samurai mythologies. But Logan’s connection to Mariko (and his obsession) can’t be repressed for too long, leading to a final confrontation and ultimately the resolution of the series.

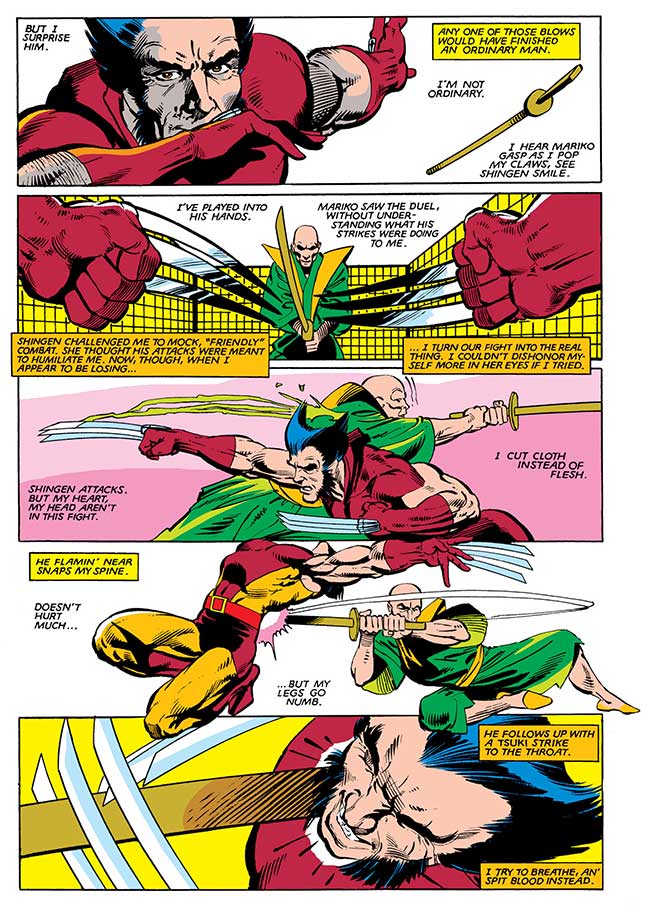

This run of issues is indeed a complicated caper. It’s fast-paced and engaging comic book writing and artistry that has since been imitated dozens of times. Miller’s art is dynamic and bold, his use of silhouettes and borderless shapes is some of my favorite comic art. The neon signs in the book are gorgeous and float in the air like fairy sculptures. Miller (and X-Men artist Paul Smith in the main series) use minimalism and stark panels to provide cinematic, drama-filled moments that are instantly iconic.

Now for the other part: Miller is not a great guy at all. His politics are cringy, and his later work can be both bigoted and bad. But here, back in the early ’80s, he was doing some amazing work that can be appreciated for the time capsule that it is. Again, whether you choose to read this work is up to you.

And let’s take a moment to celebrate letterer Tom Orzechowski. Over 25 years, Orzechowski lettered something close to 6000 pages of Claremont scripts, he’s an expert at squeezing massive amounts of dialogue into word balloons while remaining legible and leaving room for panel art. His block-style lettering is some of the best in the business and it should be celebrated more often! The Wolverine Logo he designed for this book, inspired by the art deco lettering trends of the 1930s, is a gorgeous angular moment of drama, itself placing the series in noir traditions before the reader even opens the comic.

While Wolverine has evolved over the past 40 years (I mean they didn’t let him smoke after the ’90s) his characterization has been relatively consistent. He’s always a loner who inexplicably is on every superhero team, he’s always cantankerous and brusk, and he’s always the best there is at something-something. Place this first solo series next to Benjamin Percy’s current run on Wolverine and you’ll see essentially the same character. That may not seem remarkable considering the nature of superhero comic books but when it comes to a character like Wolverine his perpetuity feels elemental. “A Wolverine-type” would be a character description that many would immediately understand.

This original series follows the basic ideas of the monomythic hero’s journey, from the outset of the adventure, through the trials and the hero’s fall, to the eventual return when the X-Men receive an invitation to Logan and Mariko’s wedding. Wolverine is now a mythic figure (whether we like it or not) and his ubiquitousness is here to stay for many years to come. This series is an important piece of comic book history that changed the nature of graphic storytelling and launched Wolverine into stardom. Warts and all, and that means something ‘bub.

Read more of the Heroes of X/History of X series!