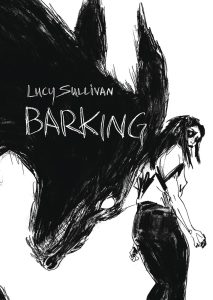

Barking

Barking

Creator: Lucy Sullivan

Publisher: Avery Hill Publishing

Publication: February 2024

After I read Barking for the first time, I had trouble sleeping through the night. Usually, my routine for a new graphic novel is that I’ll grab my copy, physically or digitally, with something to drink on a weekend night, and try to go through it all in one sitting without interruption. I’ll sleep on it, and then first thing the next morning I’ll hammer out a few hundred words that will try to give me the general shape of my feelings on the book that I can refine later.

This process did not work for Barking. I read it on weekend night, could not get to bed, and then spent a few days with the impression of the book living in my mind before I ever had the coherence to put down what I was feeling into words. When something strikes you so directly, you almost feel disconnected from time. I was floating through a few days, reliving the past with the full sensation of the comic still in my mind, and there was a joy and clarity to it that I did not want, or really even could not, ruin with words laid out in a formal review.

Barking is not an easy book to read, nor is it an easy book to talk about. Lucy Sullivan here is attempting to demonstrate through the comics form how one gives life to their feelings in a way that not only connects with others but provides a sense of clarity through representation. In particular, Sullivan is working through the double feelings of depression and trauma, while also dealing with the epistemic alienation of mental health facilities and the lack of clarity over how to properly contextualize the events that induced the trauma. This is a comic about how best to visually represent these feelings that gives the reader an understanding of the experience, while also allowing for some catharsis. This is not about giving us answers to those feelings but rather finding satisfaction in knowing these disorienting, monstrous emotions can indeed be articulated in the first place.

Depression and trauma are powerful feelings, specifically the kinds that rip us out of reality. When Hamlet said “time is out of joint” to articulate the confusion and pain of the present, we could understand that today that losing our grasp of time and spatial orientation is what characterizes a traumatic experience. Sullivan creates this feeling of temporal dislocation by muddying the clarity of the basic units of comic book storytelling: the panels.

Where each panel in a comic usually indicates a specific moment in time, freeze framed to provide perfect, sequential clarity. Here, Sullivan dissolves those panel borders, creates them in haphazard ways, or overlaps several moments at once to intently disorientate the reader’s experience of the flow of time in a comic.

Additionally, we cannot easily move from panel to panel in the chaos because of the overlapping lettering, and the repeated phrases. The comic is the quintessential representation of sensory overload. We find ourselves constantly reaching out for answers, clarity, meaning. And in return we find disorder, chaos, and self doubt. The reading experience is not an easy one, but this is precisely the intended effect. We feel in the moment the weight of emotions too heavy to process neatly.

The title and animating force of the comic, the “barking,” finds visual representation as a large, shadowy dog that hounds Alix through her journey. The sensory overload would be powerful on its own. However, the presence of this tenebrous creature that forces us to move from page to page, feeling a sense of danger and urgency while at the same time only half understanding what might be happening around us, creates a palpable sense of anxiety.

Sullivan finds success in her ability to convey the large, messy emotions on the page but she also develops a critique of the state of mental health treatment that goes beyond representing Alix’s feelings. Alix finds herself hounded not only by the darkness chasing her, but also the forceful way we communicate and hound people experiencing trauma to simply move past it. There’s a lack of perceivable care for her treatment, and an even greater lack of genuine outreach from others with the exception of one character she speaks to on a more regular basis. The comic is ultimately a treatise on the isolation created by and expected by depression that becomes more difficult to navigate without support, and cultivates the distrust of others who might be able to help but cannot understand your pain.

In reading Barking, you see how thoroughly Sullivan has crafted and transformed her experiences into the story, but you also feel an intimate connection to the work if you know the places Sullivan is coming from. The persistent unease I felt after reading this comic evoked memories, experiences and a general disjointedness that I hadn’t thought about in quite some time. Like a good meal, photo album or diary, the comic has the ability to transport you emotionally to a place you didn’t think you needed to go.

Barking is a rich, complex work that is not for everyone. The comic is about a difficult topic and is just as difficult to read. However, that is the core of what makes it so worthwhile. Lucy Sullivan embodies the idea that art is about articulating our emotional interior in a way that goes beyond simple words. This is a comic that instills an emotional connection that feels real, powerful, and deeply memorable.

Final Verdict: Buy

Check The Beat’s review section for more graphic novel reviews!