By Paolo Chikiamco

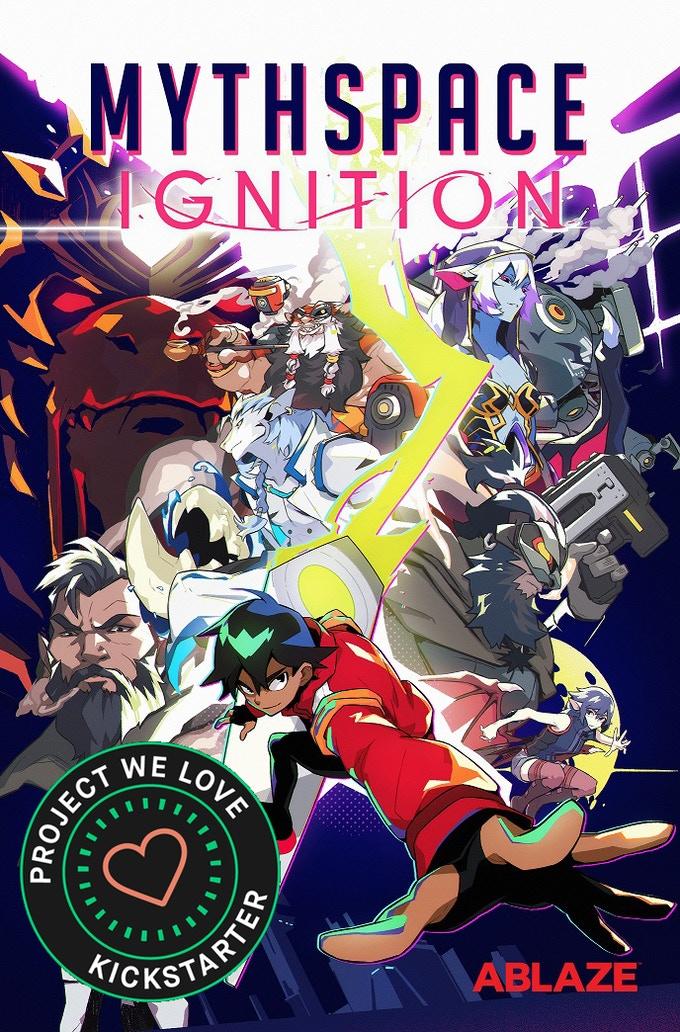

[Editor’s note: Paolo Chikiamco is the creator of Mythspace, which is currently being crowdfunded for American publication via Ablaze. The Filipino “komiks” scene is a unique and vibrant one, and Chikiamco graciously wrote the following overview of where it stands after the disruption of the last few years.]

In her 2017 graphic novel “Dead Balagtas”, Emiliana Kampilan connected four love stories by using the earth sciences as metaphor. The rise and fall of mountains brought about by the collision and movement of subterranean forces made for powerful imagery, easily linked to the tumultuous and ever-changing nature of human passion.

Now, as I try to describe the state of the Philippine comics (or komiks) community in 2022, I can’t help but find myself drawn to the same metaphor. The events of the past few years – both good and bad — have shaken up the community immensely in a short amount of time. Some of these changes are good, and some are more permanent than others, but it’s clear that the landscape has changed drastically.

The Pandemic Fault:

When the Philippine government finally recognized the threat of COVID-19, it placed much of the country under what was to become one of the longest lockdowns in the world. Before COVID-19, much of the komiks community revolved around a circuit of conventions, punctuated by the semi-annual events run in Metro Manila by either Komikon or Komiket. Crowded and rambunctious, the import accorded to these conventions (and the face-to-face interactions that took place there) is the reason why I use the term komiks “community” as opposed to komiks “industry.” This community accrued naturally around Komikon when it began, and only broadened when Komiket was established with the specific aim of fostering that sense of support and camaraderie.

The majority of the print comics created in the Philippines are self-published books, with small print runs and priced almost at cost. Many of the comics that are eventually released through traditional publishing outlets start as ashcans, and the launch of the collected editions are usually set to coincide with these same conventions. It’s this small-press environment, where readers are able to directly interact with creators at their tables, that creates the feeling of solidarity between readers and creators alike, and which serves as the medium through which buzz is generated and sales are made.

When the lockdowns came, all this was suddenly gone. While both Komikon and Komiket transitioned to online conventions, these were by nature very different to the vibrance of the physical meet-ups, and also offered no easy way to translate attendance to sales for comic creators. There was also the personal toll the pandemic was taking on individuals as jobs were lost and medical bills were incurred. As I write this, it is likely that large physical gatherings may soon return (they already have for the election sorties of this year’s Presidential candidates) but that doesn’t mean all the conventions will, or that they will be the same type of events: the Komikon organization has taken a hiatus for 2022, stopping even online events. Meanwhile, Komiket has pivoted their online conventions to the training and education of creators, as well as to facilitating collaborations between them.

Trenches of Loss:

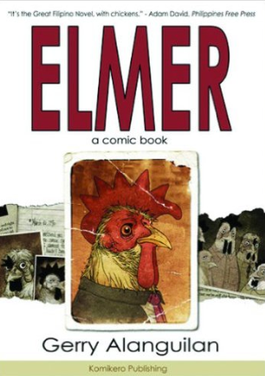

The shocks to the komiks community had actually begun in the last days of 2019. On December 21, 2019, komiks legend Gerry Alanguilan died. Known for his work as an inker and collaborations with Lenil Yu, as well as his Eisner award winning comic “Elmer”, Gerry was a mentor and inspiration for many Filipino creators. There was no one that was more passionate about komiks than him, whether about its past (he founded the Komikero Komiks Museum in San Pablo) or about its future. Until he was sidelined by health problems he was a regular at conventions, still trying to keep up with the newest independent komiks. He was an outspoken blogger, and whenever he would dispense advice, it always carried weight.

Less than a year after Gerry’s death, the komiks community also lost Danry Ocampo. Danry was not a komiks creator, but it wouldn’t be much of an exaggeration to say that much of the spirit that animated the komiks community came from him. He was a tireless supporter of local komiks, a constant presence at the conventions and in online discussions, and his gentle enthusiasm was an anchor for many struggling creators.

The loss of both of Gerry and Danry within such a short span of time was a definite blow to the community, coming during a period when most were already struggling with anger and anxiety because of the pandemic.

The Trese Effect:

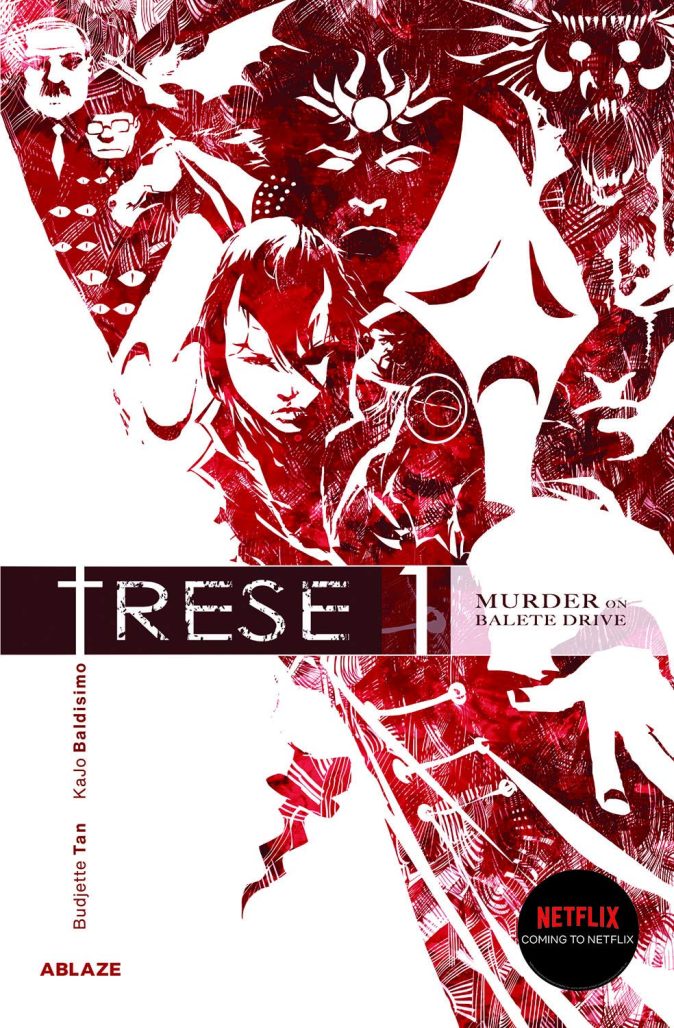

Not all the forces acting upon the komiks community resulted in chasms. There were peaks as well, particularly when it came to awareness of komiks on the international stage. 2021 saw the worldwide debut of the Trese animated series on Netflix. The show was preceded by an aggressive marketing campaign, and proved a ratings success in the Philippines and abroad, raising global awareness of Philippine-made comics to a record high.

I can personally attest to a noticeable uptick in interest in our work after Trese premiered. Suddenly we were getting feelers from several parties at once. Many of these exploratory talks didn’t go anywhere, but works like Mythspace were clearly on the radar now. International publishers such as Tuttle took a more active stance towards the Philippines, picking up “After Lambana” by Eliza Victoria and Mervin Malonzo, the first of several that are in the pipeline. Ablaze, Trese’s international publisher, also asked to work with me and my team to release a remastered version of Mythspace, which is what led to our current Kickstarter campaign. Ablaze also acquired the wordless comics of Manix Abrera, one of the most popular comics creators in the country, and Fantagraphics picked up the wonderful Meläg, from Bong Redila.

The government has taken notice of this interest as well. For the first time, the National Book Development Board will be sending a delegation with books to be featured at the London Book Fair, and graphic novels will be well represented.

And all that is just the tip of the iceberg.

Building and Resisting:

While the loss of the conventions is still a blow to the komiks community, it hasn’t stopped Filipinos from making comics. While Gerry is gone, his exhortations for creators not to sell themselves short and to create their own characters and comics still reverberate.

The prolonged lockdown has served to accelerate the evolution of online retail and courier services here in the country. With much of the populace now used to buying goods online and having these delivered to their door, some creators have taken to selling directly to their customers (such as the zine veterans at AGW Komix). Others, like Mervin Malonzo, have created their own publishing enterprises, printing and hosting other creators at their stores. (Of course, Mervin is an outlier: an artist, a businessman, and now an award-winning animation director all in one.) There are also many still happy to have a third-party handle the backend in a more traditional way — and while foreign publishers have entered the fray, local komiks publishing has shown a renewed vigor. Komiket has taken the role of both mentor and publisher through its Philippine International Comics Festival venture (as well as through its Secret HQ store), Avenida Books has risen from the ashes of the much-respected Visprint, and Anino Comics has become more active in soliciting work.

But the last few years has also seen a rise in the number of creators putting their work online. The lockdowns were an obvious contributing factor, but so has the arrival of more dependable webcomic hubs such as the Webkom Alliance, Kudlis, and Penlab. Several of these hubs have also entered the print publishing business themselves, such as Penlab through a partnership with print veteran PSICOM, and MIXD.cc through print on demand. These sites have also contributed to a democratization of komiks and a lowering of barriers to entry, as sites like Webkom Alliance accept submissions at any level of talent. This has led to the development of communities and networks outside of those that blossomed in the convention circuit.

Another factor has been the success of creators such on sites such as Webtoons (like John Amor, artist for Urban Animal) or on social media, with popular works such as Hunghang Flashbacks, Hulyen, and particularly Tarantadong Kalbo (by Kevin Eric Raymundo). The latter in particular has made a tremendous impact during the pandemic years as his strips synthesized the anxiety and anger Filipinos felt over the way the government handled COVID-19. This reached its apex when his image of a single raised fist in a sea of submissive straight fists (the symbol of Philippine President Duterte) became a viral symbol of resistance against blind obedience to power, a movement aptly named Tumindig. The upcoming national elections have also seen an uptick in the appearance and use of komiks as a means of political criticism and advocacy, with several Presidential campaign using komiks about their candidate as campaign material.

Sequential Currents:

The state of komiks cannot be separated from the state of the world, and for the past few years the state of the world has been a garbage fire. But the advantage of being a community rather than just an industry has been the level of support Filipino creators can trust to receive from their peers, at whatever stage of their career. While the community is not monolithic, and there can be intense disagreement as to what needs to be done for creators, there is no shortage of effort made towards finding tangible solutions. The result is a diversity of ways to be a komiks creators, an abundance of choice when it comes to the kind of komiks you create and how you get these before your readers.

The fact that self-publishing has been the norm in the komiks community for the past two decades means that the scene is fairly accepting of a wide diversity of content. We have high adventure and hospital hijinks (with or without ducks); stories about ancestral curses, about affirming a child on the autism spectrum, and learning Philippine sign language; “evil” fourth graders and crime fighting call center agents; gory aswang, the latest work of the legendary Alex Niño, and of course the iconic Zsazsa Zaturnnah.

Not every book will achieve (or will even aim for) mainstream recognition, but in general the success of one is welcomed as good for the whole. This may be due to a concerted effort of many veteran creators to pass on what they’ve learned. Even during the lockdown this transfer of knowledge continued, through panels and workshops, or through informal conversations on podcasts such as the Indie Komiks Podcast and Jon Zamar’s Komiks Kwentuhan.

It is the nature of a community to share, and to stand on each other’s shoulders. As more Filipino creators reach their goals, they gain knowledge of the techniques necessary to hone their craft, present it to a wider audience, and make a viable living from their work. That knowledge doesn’t stagnate but spreads, motivates, and animates others who aspire for those same goals.

How is the Philippine comics community in 2022? Battered but hopeful, feeling the pressure and using that to push upwards to new heights, new air. Building… maybe not mountains, but terraces: wide steps with room for many, making sure that the path for those to follow will not be as steep.

Thanks for the article. I had no idea comics in the Philippines were mostly self-published. Some of my favorite artists are Filipino: Francis Manapul, Nestor Redondo, Alex Niño, Alfredo Alcala, Gerry Talaoc, Rudy Nebres. Are there many women cartoonists? Was Captain Fear just Alex Niño’s self-published comic repackaged for DC?

Comments are closed.