Larry Fessenden is indie royalty, a director that knows the value of storytelling not by virtue of its budget but by virtue of artistic vision. Whether it’s a contemplative vampire story about the dangers of romance (Habit, 1995) or a tale about a mythical beast from Algonquian legend that deals in retribution (Wendigo, 2001), Fessenden movies always feel well researched and respectful of its influences. This is also the case with his latest movie, Depraved.

Having said that, Fessenden is not one to shy away from taking the source material and bending it to his will, and Depraved is perhaps the best example of this. Depraved sees Fessenden tackle Mary Shelley’s classic, Frankenstein, one of the hardest movies to adapt given the long history of loose adaptations it brings with it, most notably that of Universal Pictures in 1931 (in which Boris Karloff staked his own claim on the story thanks to his performance as The Monster).

Depraved might be the best adaptation, evolution even, of the novel yet, and it’s one of the best I’ve seen in years. What makes it special is that the acclaimed director found a way to make this interpretation of the story difficult to separate from his vision, a thing very few have accomplished when dealing with the book.

One word of advice, though. To really appreciate just how excellent of an adaptation this movie is I recommend to not only have read Frankenstein beforehand but to also have a good memory of its story beats. This isn’t to say the movie is just “good” if you haven’t read the book, but the way Fessenden (who also wrote and produced the film) takes certain elements of the classic and how he makes them fit into his own vision for the story is just an absolute treat to pick apart while watching the movie. It heightens the experience.

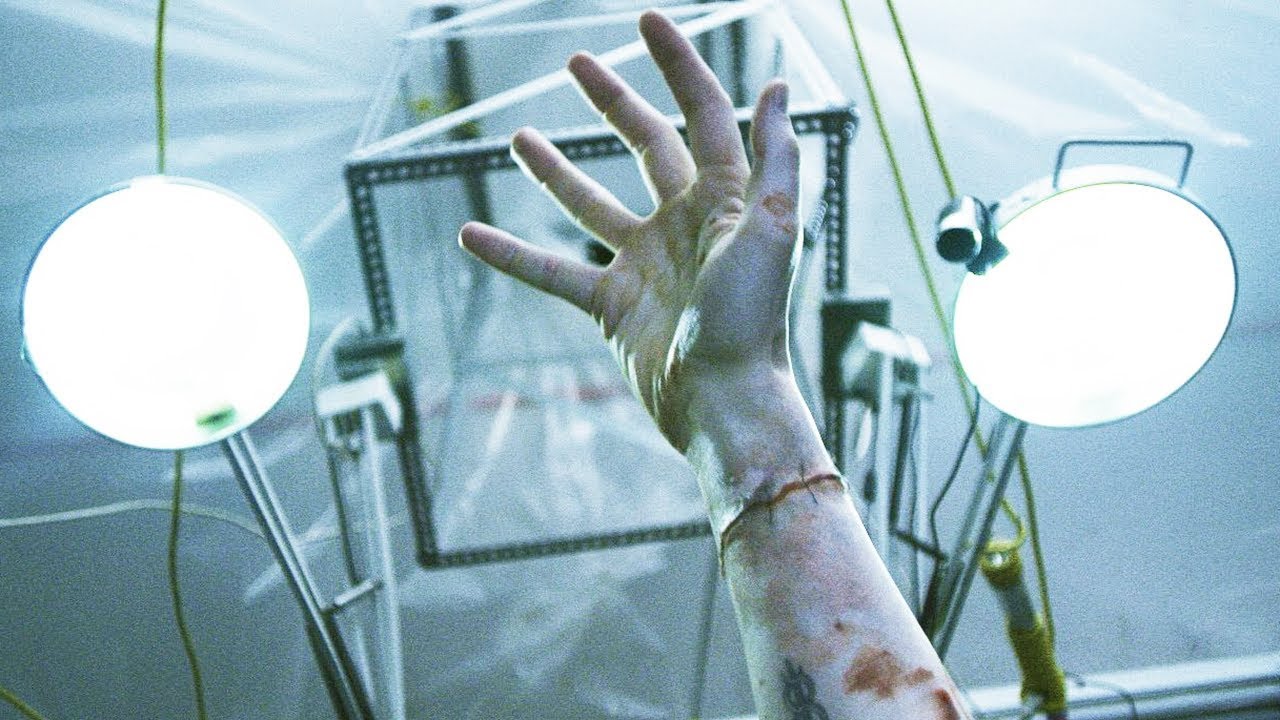

Depraved’s Frankenstein (the doctor, not the monster) is a war veteran, called Henry, who came back with PTSD. He was a medic and he wanted to save every wounded soldier he came across while in the Middle East. This is where the character finds his purpose and why he decides to give life to a man composed of body parts belonging to different people. Just having him be a veteran gives the character such a different sense of being and imbues him with so many other dimensions. It allows the audience to come up with new readings based on the differences between the movie and the original story.

As is the case with the book, Frankenstein is surrounded by friends who constantly worry about his mental wellbeing and the idea of parenthood is as central to Fessenden’s version of Frankenstein as Shelley’s. Revealing too much would spoil the experience, but fans of the book will have more than enough material to make the connections. And this isn’t just Easter eggs. Everything is woven into the story, which is very much rooted in a 21st century mindset.

David Call as Henry (the movie’s Frankenstein) and Alex Breux as Adam (Frankenstein’s Monster) approach their roles as “creator” and “creation,” as “father” and “son,” in a very measured and nuanced way. Each scene involving the two shows a delicate balance between tenderness, intensity, and regret that beautifully captures the timeless relationship between the two characters.

Having secured the essential elements of the story, Fessenden proceeds to play with the formula. For instance, the movie dives into the idea of memory and trauma quite often. These scenes are clearly marked by colorful shapes dancing across the screen as we’re treated to several looks at the past to try and put together the chain of events that led to the creation of Adam. It was a very interesting touch that managed to stray far from becoming a gimmick.

One other great change to the original was the film’s treatment of ethics in experimenting with the limits of life and death. Henry’s friends, for instance, are invested in the experiment succeeding in order to later replicate it and sell it as an expensive solution to death, preferably in the military field. One particular friend, called Polidori (I’ll let you figure out that reference), played by Joshua Leonard, is basically portrayed as a pharma-bro hoping to become rich while young by doing whatever it takes to sell the procedure that made Adam possible. His attitude and the way he carries himself is clearly based on the dangerously influential presence of young entrepreneurs and their problematic focus on “positivity” as a brand.

This turn on the supporting characters’ roles took me entirely by surprise, but what was most impressive was how well each change to the original story clicked with the movie’s interpretation of it. It made the movie unique and allowed Fessenden to create something that is truly his.

It’s unfair to view Fessenden as a master of storytelling on a budget. The things he brings to his movies should not be taken as simple adjustments predicated by the amount of money he has to work with. Fessenden’s strengths lie in his ideas on what makes a great film, and they are especially noteworthy because they make for great storytelling regardless of how big or small a budget is available. Depraved is a good example of this and further cements Fessenden as a master of storytelling.