Animator, director, producer and screenwriter of works such as Primal, Samurai Jack and Dexter’s Laboratory Genndy Tartakovsky was at C2E2 2020 over the weekend for a special spotlight panel. During “Genndy Tartakovsky: A Homecoming and Retrospective,” the creator talked through his start in Chicago at Columbia College and into the creation of some of his landmark series. In the panel’s overtime minutes (no one wanted it to be over) he also made a few announcements about his upcoming projects: Fixed, The Black Knight and provided a first look at the next season of Primal.

Ironically, it seems Tartakovsky was well aware that his presentation would go over from the beginning. Without wasting words, he told the thrilled audience that he’d be explaining the journey of his entire career, as well as his time in academia. His story began in 1974, in Communist Russia, with a young Tartakovsky first becoming enamored with cartoons. One in particular was, translated to English, Wait Till I Get You Now. The animator loaded up a clip of the show but – surprise! The sound wasn’t working. After a few failed attempts, he opted to create his own in a very adorable, very human moment. Eventually, though, the techs behind the scene succeeded, and fans saw what’s essentially a Tom and Jerry scenario in which an anthropomorphic wolf tries to attack a rabbit. I couldn’t find the exact clip from the panel, but a quick google search will get you where you want to be.

Anyway, it wasn’t long before the Tartakovsky family would move from Russia to Chicago. He grew up, continuing to love cartoons and failing to fall out of love with favorites like Popeye, Looney Tunes and the aforementioned cat and mouse show. In Chicago, though, there wasn’t much of an animation scene when it came to work. So, instead, he decided he’d go into advertising and continue his passion on the side (sounds familiar). It was then that he was accepted into Columbia College Chicago. In a twist of fate he never intended, his first semester led him to an animation class – one he hadn’t even realized the school offered. His professor, an old Popeye alum, showed him the ropes, and Tartakovsky stopped lying to himself, pursuing animation in earnest.

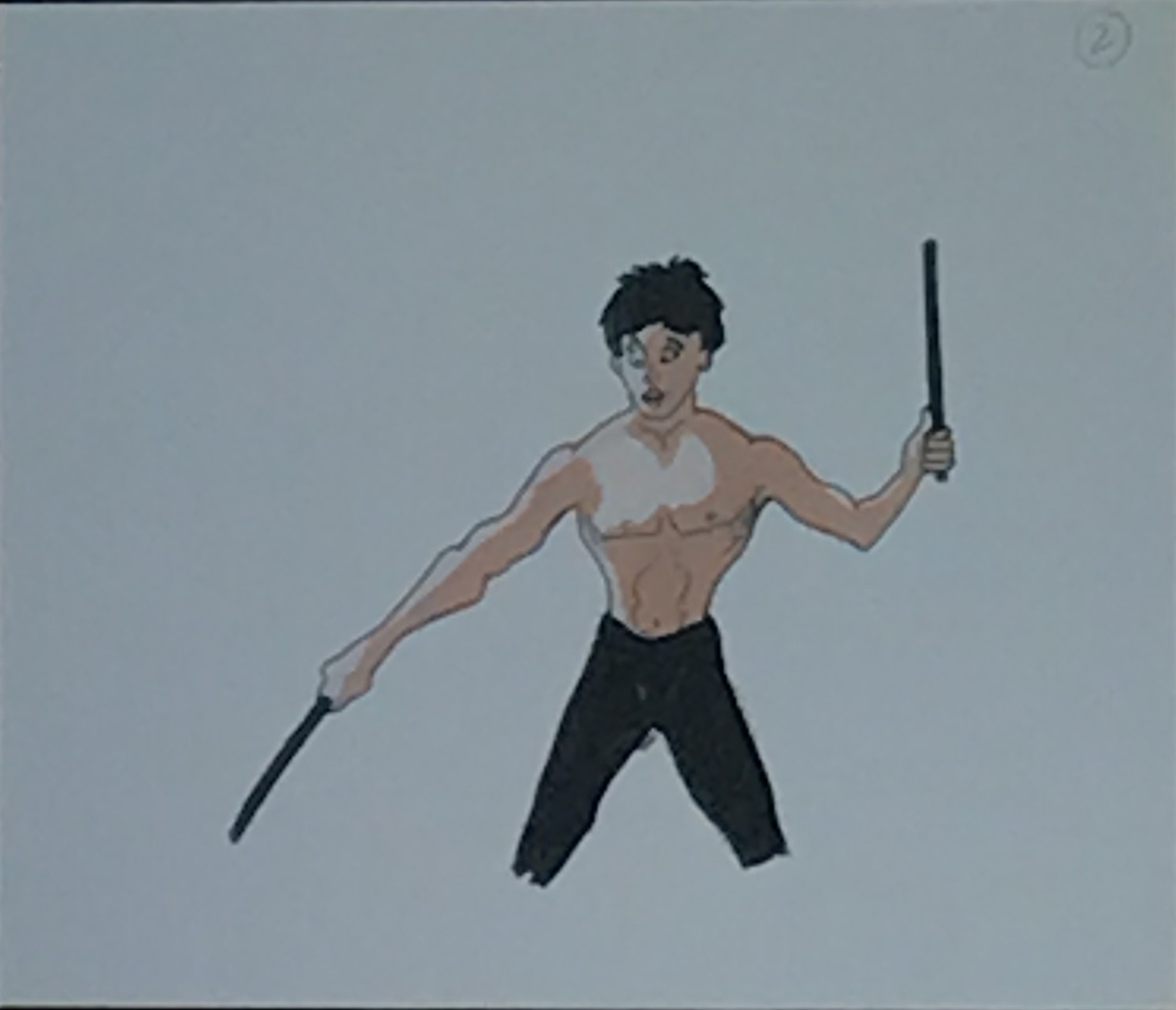

He showed fans a few of his early drawings, including one of Bruce Lee, as well as his first student film, to which he also provided sound effects and voice overs. Continuing his story, later he met someone (he forgets who now) who was doing a multimedia play. They needed a bit of animation, so the budding artist stayed up four days straight, recalling an apartment filled with animation cells he was painting. Meanwhile, his car was booted and loaded with tickets he’d never pay.

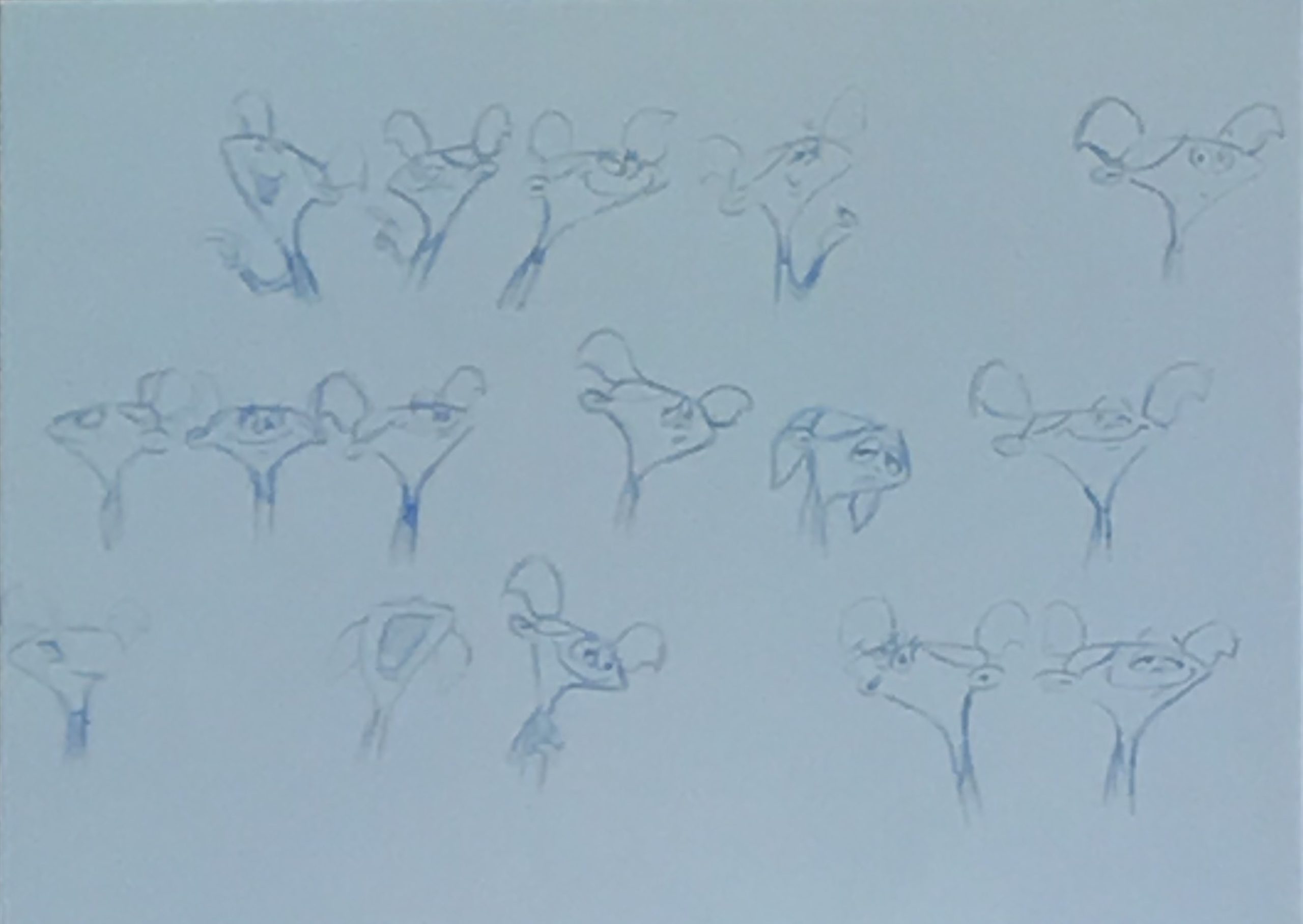

Eventually, he moved to CALARTS, a California animation school famous for its Disney alums. After sending in a shoebox full of flip books, he and his friend were accepted, so they packed the car and moved across the country… only for Tartakovsky to realize he was vastly out of his league. Tartakovsky said at this point, he was glad that he did all his manic partying while he was in high school because, while his classmates were doing just that, he was practicing, day and night. Those sessions would lead to his first hit (eventually), beginning with a girl who loved to dance. That girl would become Dee Dee, Dexter’s sister. A few of the first ever character sketches for Dee Dee hit the screen at this point, followed by narration of his realization that this girl needed a counter; someone obsessed with science. Tartakovsky then played for the audience the roughest-of-the-rough versions of the Dexter’s Laboratory pilot, including the notorious “what’s this button do?” quote.

At the end of that school year, in 1992, an improved, colored version of that clip aired in front of producers hosted by CALARTS. A pair of young upstarts approached Tartakovsky, impressed with what he could do, and invited him to Spain to work on one of comics’ most beloved animated series of all time: Batman: The Animated Series. He shows another clip here of a few martial artists, before informing fans that the production company crumbled and he was left unemployed in Europe.

That brought Tartakovsky back to the States, and now to Hanna-Barbera. He worked on Two Stupid Dogs for a while with a few other up-and-coming animators, not in the building itself, but in a trailer on the highway. He told fans that anime was dying around this time, so for Nickelodeon and Hanna Barbera to be putting out their own original programming was unprecedented. His superiors, he said, had no idea what they were doing and weren’t interested in admitting it, either. So, no one on the team knew what they were doing. It was tough, but it also had what Tartakovsky called “benefits.” At one point, Tartakovsky realized the person doing the walking cycles (now a Disney animator) for the dogs was less than great. He tried to point it out to his manager, but they didn’t care. So, in the middle of the night, Tartakovsky completely redid those animations, all by himself. He showed his manager, who loved them. He realized then, that his animation actually worked. People liked it.

That’s when Dexter’s Laboratory finally found its stride. He took those original sketches, the framework he left behind years ago, and showed it to Cartoon Network. The pitching room consisted of about 15 execs, he says, and he had about seven minutes to get his idea across (he was also only 24 at the time). He talked a bit about how the show took off and how he landed his first Emmy nomination, before realizing how short he was on panel time.

Powerpuff Girls was next for him. It treated him well during its run, but he soon realized there was something more he wanted to do, especially looking at action cartoons of that era and his disappointment in them. He started developing a quiet warrior, who would star in a show focusing on stylized action and cut robots. He pitched that, verbatim, to his producer over dinner, and by the time dessert came the idea was approved; Samurai Jack began in earnest.

Tartakovsky told fans a bit about that development, talking to (though eventually turning down) George Takei for the voice of Aku, before ultimately deciding in favor of Mako. Then, he played a clip of the Samurai Jack episode “Birth of Evil,” and chatted about the show’s critical acclaim. For years, Tartakovsky said, he, his wife and few other animators would go to the Emmy’s for Samurai Jack nominations, only to lose to about 50 writers from The Simpsons. Until “Birth of Evil,” that is. He remembered sitting there, with his rag-tag team, not even recognizing that their show was announced as a winner. They only realized they needed to accept their award after hearing the Simpsons team’s exasperated “what the &$%#?!” It ended happily, though. He saw Simpsons creator Matt Groening in the bathroom later, who congratulated him and said he loved the show.

George Lucas would take some more schmoozing, though. Following Samurai Jack, Tartakovsky’s next major project would be Star Wars: Clone Wars. Initially, Hasbro wanted an excuse to make some more toy money, so they nudged Lucas into greenlighting a series of shorts, no more than a minute in length. No one can ruin Star Wars in a minute, Tartakovsky joked. But he wanted more. He negotiated up to 3-5 minute shorts. A third party took that back to Lucas, who only agreed because of his son’s ringing endorsement of Samurai Jack. Lucas’ only stipulation was that the story couldn’t be progressed at all and that no one should bother him ever again. Until the season 2 finale, that is, when Lucas finally came around on the show and asked Tartakovsky to introduce General Grievous.

That was epic, as we all fondly remember, but it wasn’t enough. Cartoon Network was changing quickly, with people moving in and out with the 2008 recession in full swing. Still passionate, though, he tried to put out a low-budget feature. He raised 3.5 million with his new studio, but he couldn’t find a buyer. A film about photorealistic dinosaurs, along with a Viking project, were both lost along with the studio’s remaining funds. With no other choice, the animators who stayed with Tartakovsky made commercials for a nicotine patch company who, as it turned out, also went under – and never paid up.

Eventually, Tartakovsky would find his way back to Cartoon Network for one of his lesser known works, Sym-Bionic Titan. The network, unfortunately, was still struggling at the time trying to find its identity again and only saw the show as a machine for toy production. Apparently, they hadn’t seen Tartakovsky’s work. It only lasted 20 episodes and Tartakovsky confessed it never found its identity either – but! It is on Netflix now and the animator was quick to hint that if fans rediscovered it, there’s a good chance Sym-Bionic Titan could get a second chance. “Who knows?” he said coyly.

He talked, then, about his quick dive into live-action and the MCU. He told the audience about working on the final action sequence of Iron Man 2 (the one where Iron Man and War Machine tear a bunch of robots apart). He actually worked directly with Don Cheadle, in the Iron Man suits, and put together test footage of exactly what he envisioned. Tartakovsky even brought that along for the audience to see. Although there were some bumps along the road, the theatrical version was beat-for-beat what Tartakovsky envisioned, he said.

From there, Tartakovsky went into third gear as the time ticked down. He briefly mentioned working on Hotel Transylvania, the Popeye animation that never was and a bit of the development on all those. Behind the scenes of Transylvania, Tartakovsky found himself pining to return to action. When he wasn’t working on the kids’ feature, he was working on the bones of Primal and the final season of Samurai Jack.

It was the reception of that show that pushed Primal from a kids’ show to what it is now: a 10 episode season with no dialogue. He spent lots of time developing the dramatic tone and, eventually, realizing it focused heavily on the relationship between man and beast. It was new to him, and he became excited about the idea of exploring empathy through that dichotomy. Tartakovsky pitched the show as a baby seal and polar bear against the world; one could eat the other, sure, but it’s even better if they team up.

And, ever generous, Tartakovsky brought the audience a first look at the second season of Primal. No pictures were allowed, but I can promise it’s gruesome, funny and beautifully animated – all, of course, without dialogue (though there is a dash of screaming).

On the subject of his most recent projects, it only made sense that Tartakovsky would address his upcoming features. Both were mentioned briefly before, but he did have some sparse details that have yet to surface prior to this panel. The first feature is a return to humor. Fixed is an adult animated feature about a dog who learns he’s going to be neutered, and what he does with his endowment in his final hours. Juxtaposed with that is The Black Knight, which he described as an action epic with no talking animals, no sidekicks – he brought up Gladiator and Braveheart specifically before adding that we can also expect a fair share of ninjas and samurai knights.

From there, seven minutes after the panel was scheduled to end, he recapped his mantras and what got him here: Relationships, some luck and hard work. He told fans don’t waste an opportunity and to always have their own point of view.

“2914 in communist Russia”

Damn commies

That’s Tartakovsky’s secret: he’s from the future.

(This has been corrected.)

Comments are closed.