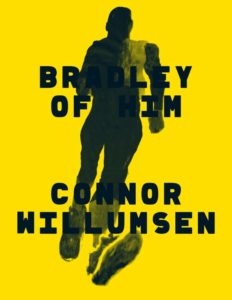

Bradley of Him

Written and illustrated by Connor Willumsen

Published by Koyama Press

A man who only knows the business of satisfying himself blunders into a sublime gift. The connection of presence to the world, the erasure of self, is beautifully rendered in full acid blotter psychedelic glory by Connor Willumsen, but it’s all lost on Bradley of Him.

Willumsen’s graphic novel is inspired by folk art, mystic patterns, and sublime, kaleidoscopic geometry. But this isn’t a seer climbing a mountain. This is a method actor, sort of, running to be Lance Armstrong and running for the Academy Awards, running will get him and, give the sun time enough time to fry his mind, running for running.

He’s doing it in Vegas, he’s doing it in public. The desert tanglewood is transformed into casino showrooms out of Koyaanisqatsi, raw capitalism both beautiful and awful. It’s an autopsy of the total separation we can cultivate in public life, the dark valley of cognitive dissonance that life falls into. Ignoring the humanity he is a part of does not make them cease to exist, and yet they do.

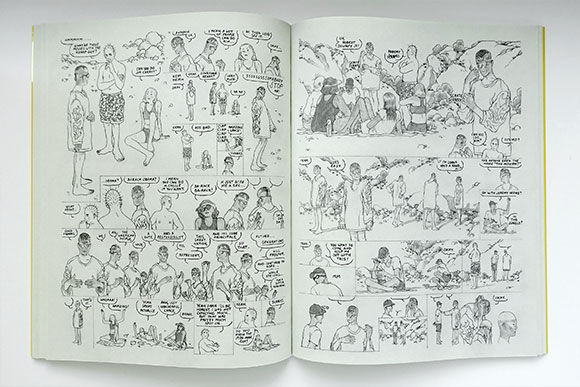

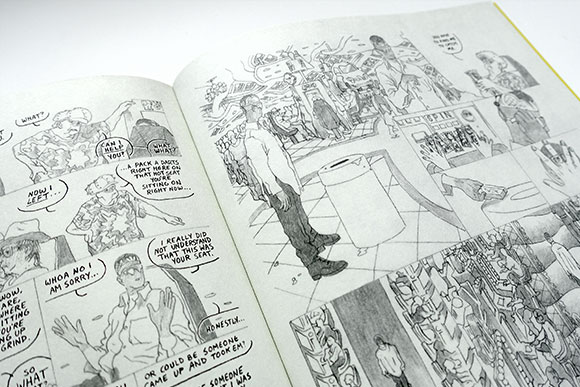

He runs through the crowd, through folks in trouble, strangers, family, like flying through a cloud. Even Bradley’s thoughts commingle with the masses as the lettering crawls through the art. People are a maze to find a path beyond. They are parkour. They’re nothing. Every interaction with another human being and this anti-sage is just raw painful. Watching the will of the rich and the obligation of the working stiff grind against each other like broken gears killing the watch. Concierge, cop, medic, chef, custodian, waitress: Bradley has an army of uniformed servants that maintain his illusion of devotion to craft. He’s trying to ascend into glory, to reach an understanding of character worthy of golden statues, running circles around America’s greatest monument to excess.

It is a beguiling task to navigate the bleak mental terrain inside Bradley of Him, an apartment of quiet, underused rooms and movie memorabilia. But perhaps Willumsen undermines enlightenment also. Bradley hones his craft doing burpees. But what talent isn’t practice accrued? By rights Bradley, empty of self, should be running to Nirvana. He jogs past, not looking, and misses it, nonstop self-assurance paired with a total inability to function.

Bradley of Him feels like a new cult classic, an addition to the lexicon of modern outsider storytellers and haunted urban dreamers. It’s densely packed with exchanges, inventories, people. It’s Nevada, your choices are crowds and air conditioning or nobody and the baking sun. Willumsen loads each page. Figures appear over and over, a phénakisticope of myriad angles, a hundred bees locked into a honeycomb with largely invisible edges. Willumsen has mostly done away with drawing panel borders. The art is held behind walls that aren’t there, contained by where the panel should end, phantom gutters.

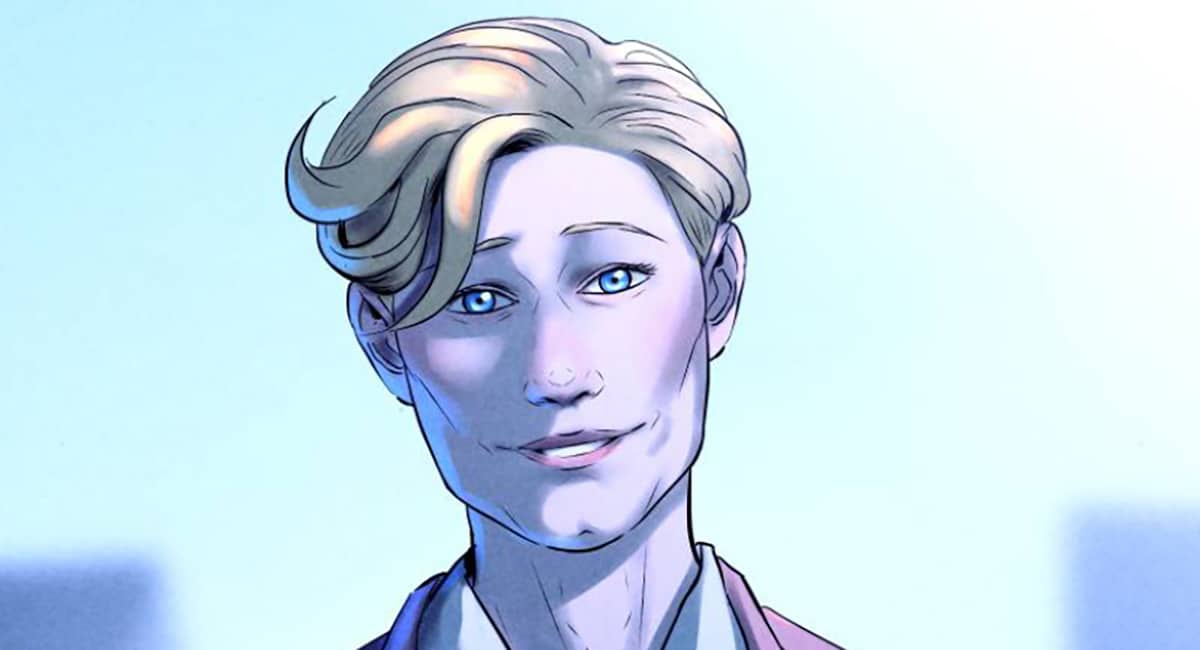

As art and words struggle for every inch of space on a page, when Bradley is throwing up in front of the cops or arguing over the nature of permanence with a buffet hostess, the structure succeeds in a natural read. In Willumsen’s Vegas, the slots and velvet ropes and scrubland vegetation, everything has a similar absence that goes with the amicably perplexing formatting. Familiar, delicate, and yet each face is a ghost missing some essential piece, spared a single line of photorealistic contour or floating up through a car window set into the desert floor. The train rides the tracks so smoothly that Willumsen has room to explore format even more.

The thoughtful composition of Willumsen’s visuals, a counterpoint to the sociopathic inner life of his subject, is what makes Bradley of Him so compelling. Willumsen has a deep understanding of each page as both parts and a whole. Very much like Chris Ware, especially the planning before penciling, and the tunneling paths of dialog, but Willumsen is as psychedelic as Ware is spotless. The bleed from story to structure creates ripples in the meaning of the story, echoes in the places that overlap. A mind freed of time and the distinction between here and fantasy wanders. From an empty road to an awards show to an uncanny transition of the body to the land itself.

Bradley is a chain of paper men, there is a giant bouquet of roses laid across the Southwest desert and each bud is Bradley, a massive jogging bunch of grapes. The reader drifts too far into Bradley, Hubert Selby Jr. territory where the broken loop carries you away. Willumsen divides the world. Shadows done as a grey wash that serve as sweet counterpoint to every inch of Earth otherwise being punished by the sun. A hotel is wrapped in a blanket of cool, meanwhile desert details are reduced to slim black edges on unbroken white. Peel off the shades and sweat-wicking cap and the tender zones of recognition and identity on Bradley’s face are scorched plains, the deep tan of skin left unprotected against the elements now the oasis.

Bradley’s dissolution of self is also inverse, from woke to joke. He isn’t Lance Armstrong but Buster Keaton, using the flexibility, strength, fragility, and the humor of the human body to tell a melancholy human story, utterly unaware of the sardonic comedy in which he stars.

Comments are closed.