By Adam Karenina Sherif

Adrienne Resha is both a contemporary comics critic and a comics scholar. She is a regular contributor and editor at the unparalleled and now Eisner Award winning Women Write About Comics, as well as an academic working towards a PhD at The College of William & Mary.

A paper which began as a coursework assignment three years ago and has seen expansion through conference performances as well as a multi-page website adaptation, The Blue Age of Comic Books was recently published in the Spring 2020 issue of the Ohio State University Press journal Inks.

In this first published academic work, Resha puts forwards a theory and conceptualisation of considerable scale. Following in the traditions of comics periodisation, Resha makes the case that we are presently inhabiting a distinctive, new age of comics. If comic books as we know them began with The Golden Age, and moved through the Silver Age, Bronze Age, and Modern Age in turn – we are now living, according to Resha, in The Blue Age of comics.

Never before has an ‘age’ of comics been so clearly defined by a single voice, let alone by a woman of colour. Resha’s argument has an immediate aptness, as well as the depth and nuance to allow the concept to go forth as a framework for both comics scholars and comics critics alike.

In short, Resha makes the case for calling this the Blue Age on the basis of the radical proliferation of both digital readers, digital comics technologies, and the key social media platforms which have made overlooked readership demographics increasingly visible – all of which share a blue color scheme.

Sherif: The Blue Age of Comic Books is a wonderful achievement and your theory is an enormous contribution to both academic and critical comics discourse. Congratulations and also thank you.

For me, the essay is well-conceived, well-argued, and strikes a tonal balance between authoritative analysis and personal reflection. Its scale is of course immense, offering a clear periodisation for the comics age we’re living through. I also particularly love the smaller details that really enhance its coherence as a concept, like ‘blue’ being intangible which matches digital, while gold, silver and bronze are physical like print. I know the idea of the Blue Age has been with you for a few years now. How much has it evolved along the way to this definitive version in Inks?

Resha: Thank you! It’s come a long way since I first started working on it, in no small part thanks to the women who read it along the way: from Elizabeth Losh, the professor whose seminar I wrote it for originally, to Candida Rifkind to Inks editors Qiana Whitted and Alissa Winn. One thing that hasn’t changed is the title of the paper, every version is titled “The Blue Age of Comic Books,” but the degree to which that has been emphasized has changed a lot. In the beginning, it was really just meant to be the title of my assignment.

The explanation for why the Blue Age was “blue” is buried in the early drafts and versions, in part because that website adaptation, the Scalar, was drafted nonlinearly. I wrote each section so that it would, hopefully, stand on its own. As it turned into a more linear paper, and as I got feedback, particularly from Candida, I really emphasized the periodization, and I moved the explanation for the color to the first paragraph. The line about blue being intangible was one of the last, if not the last, I wrote as the article was undergoing revisions. Although it’s in the first half of the article, it felt almost like putting a bow on it. Like, “this is it, I’m done.”

Sherif: As someone who sits in both the academic and critical worlds of comics, what’s your experience of switching between those different modes? Do those worlds intersect for you? And now that this piece of work is in the world, how do you hope to see people take your framework forwards? Do you expect it to be received differently in these two different contexts?

Resha: I’ve been doing academic writing a lot longer than I’ve done criticism, and, having been trained extensively in the former, I’m a relatively slow writer. But I’m a quick reader, so it takes me twenty minutes to read a single issue, 22-page comic and then anywhere between three and six hours to write an 800-word review about it. Writing a full essay, whether criticism or scholarship, takes longer. And there’s overlap. Writing Saladin Ahmed and Sara Alfageeh’s Amulet Offers Hope for Good Comic Book Arab Representation over a few days helped me draft my dissertation prospectus, which took a few months. Now that “Blue Age” is out, I’m hoping to see the theoretical framework used beyond the superhero genre. Beyond that, I don’t want to be overly prescriptive. I do expect it to be received differently in each of these contexts. Scholars are more likely to come to the idea through the article, while critics are more likely to come to it through pieces like this or those I’ve written for WWAC. For the former, the theory is likely going to be more important than the periodization, while the opposite may be true for the latter.

Sherif: Typically, each of the previous ages of comics has been characterised by sets of prevailing themes – at least within the mainstream. As you put it your essay ‘American cultural narratives informed superhero narratives, and they changed over time’. Golden Age comics have superheroes as a response to the Second World War, as well as both war and horror comics in the ‘50s which unpack the trauma of that conflict. The Silver Age leans heavily towards science fiction because of the Cold War nuclear fears that were in the American zeitgeist at that point. The Bronze Age is marked by a collapse of tradition and the complications of more consciously socio-political storytelling. I’m not entirely sure what characterises Modern Age comics to be honest, beyond a kind of fragmentation. What would you say characterises Blue Age comics thematically?

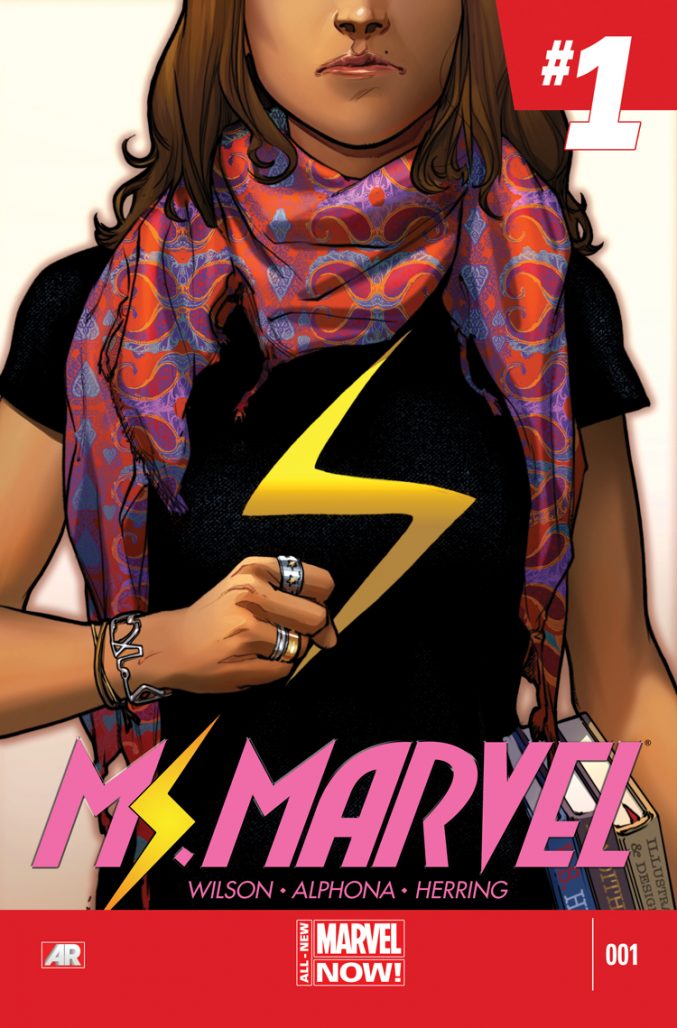

Resha: It’s going to be hard to definitively say before the Blue Age is over, particularly at this halfway point between decades, but legacy stands out as a theme. That manifests largely through legacy characters like Miles Morales and Kamala Khan, new and different (but neither all-new nor all-different) superheroes. Their origin stories were written for, if not always by, Millennials. American Millennials have lived through 9/11, the financial crisis of 2007 and 2008, and the tenure of the first Black President of the United States. We are now in the midst of another economic crisis, a pandemic, and the George Floyd protests.

The first half of the Blue Age is undoubtedly shaped by what we’ve been through, just as the second half will be shaped by what we and Generation Z are going through now, especially as the cohort of creators making these comics becomes more representative of people of marginalized identities. You can already see discussions happening about policing in superhero comics, whether about the relationship between superheroes and law enforcement or superheroes as law enforcement. We’re going to have to have a much bigger, much longer, and much tougher conversation about the genre’s past, present, and future.

Sherif: How much is the pioneering digital work in comics in earlier decades part of how we got to the Blue Age? I’m thinking of work like the chaotic experiment of Iron Man: Crash (1988), or Lynn Varley’s early adoption of Photoshop colouring on books like The Dark Knight Strikes Again (2001).

Resha: Digital coloring became the norm in the 1980s, so the argument I make in “Blue Age” about comics being digital when they’re made using computers can actually be retroactively applied to a good number of Bronze Age and most if not all Modern Age comic books. Experimental books from those Ages, like Crash and Strikes Again, can definitely be understood as the forebears of The Blue Age augmented reality and motion comics that have been published in the last decade. In those earlier texts, you can see a desire to push against the conventions not just of the genre but also of the form, to really challenge what a comic book is and imagine what it could be.

Sherif: Discussing some of those more cutting edge aspects of digital comics as distinguishing features of The Blue Age, you address some of the intricacies of guided reading technologies like comixology’s Guided View. You go on to suggest digital comics may yet offer unforeseen possibilities for more innovative storytelling within the comics medium. What do you think are the potential implications of digital comics’ untapped capabilities? Is there a chance we’ll see the major publishers move past the “fetishization” of the traditional form? (standard dimensions, page count etc. etc.)

Resha: Some of what we’re not (yet) seeing in mainstream comics is readily available on platforms like WEBTOON and Tapas, both of which are as close to Scott McCloud’s infinite canvas as we’re likely to get at present. In 2016, according to The Beat, women made up half of WEBTOON’s readership. A comic like Lore Olympus has readers in the hundreds of thousands. The mainstream comics industry hasn’t figured out how to tap into that readership, which is accustomed to a different (and often more intuitive) form of comics than what Marvel and DC are putting on stands in stores that are largely inaccessible to people of marginalized identities.

However, there has been movement away from the traditional comic book form. Marvel has published digital first comics in “seasons” (WEBTOONS, significantly, also uses seasons to describe collections of episodes, borrowing language from television, which nontraditional comics readers are often more familiar with) and DC has experimented with the dimensions of their print Middle Grade and Young Adult graphic novels as well as those of limited series published under their Black Label. Without giving too many good ideas away for free: more innovative storytelling, like we’re already seeing outside of mainstream comics, could lead to a bigger, more diverse readership.

Sherif: I’ve personally been particularly relieved to leave the collector mindset behind and enjoy a mixture of print and digital reading. As you point out, comics are now mediated through digital technology at one or more stages of production. How do you navigate the landscape of comics consumption yourself, and how much did your own reading habits influence your approach? I understand it was Kamala Khan, one of the most defining Blue Age heroes, who brought you into comics in the first place.

Resha: I started out all digital. Ms. Marvel #1 came out in February of my last semester of undergrad, by which time I pretty much knew I’d be moving to another state for graduate school. So I set up an account on Marvel’s website and subscribed to the series. I read everything using guided reading. As time went on, I started collecting the trades. The summer between my first and second years in my master’s program, I re-read the series using those and decided to write my thesis about it.

Now, six years later, I very rarely use Guided View even though I still do most of my reading digitally. But because guided reading taught me how to read comic books, I was able to recognize its utility as an accessibility tool, which isn’t how a lot of comics studies scholars, a good number if not majority of whom grew up reading the kinds of comics they write about, see it. It was really important for me to include my own perspective as a digital reader in “Blue Age” because it wasn’t one I’ve seen represented in comics theory.

Sherif: Something you reflect on throughout is how the Blue Age really marks a greater recognition for more marginalised readers who have traditionally been overlooked, both within the comics community and by publishers as a market in terms of “affective economics”.

What you highlight around accessibility, and the overlap of struggles is particularly striking: “Neither people with disabilities nor women nor people of color (or any of the people who exist at the intersections of these identities) can claim full citizenship in comics culture on their own”. To me this feels like such a thoughtful call to solidarity and co-advocacy. How strongly do you feel there’s a correlation between the over-represented audience and print, and the under-represented and digital?

Resha: I think it’s less correlations of “over-represented and print” and “under-represented and digital” as it is “over-represented and mainstream” and “under-represented and literally anything else.” Mainstream superhero comics are overwhelmingly made by cishet white men, that’s as true today as it was eighty years ago, and those men (especially those who were fans before they were creators) are often, intentionally or not, making comics for people like themselves. People of marginalized identities have always read those comics, but they can now access (and produce) alternatives more easily because of the internet and digital technologies.

Mainstream comics got a taste of what it meant to appeal to minoritized readers with Ms. Marvel, a digital bestseller, but neither Marvel nor DC has managed to reproduce that success (although Marvel has arguably tried harder than DC, which currently has only one solo title featuring a superhero of color on stands: Far Sector). Their failure to do so has been made to seem like it’s the fault of readers. That failure falls squarely on the shoulders of the publishers, editors, and creators who privilege existing readers over potential ones.

And it’s systemic: it cannot be divorced from the sexism, racism, ableism, and other forms of inequity that the comics industry (not just publishers but also distributors and stores) has perpetuated. I wrote that line in 2018. This summer, as we’ve seen creators come forward about abuse, we’ve seen it put into action on an individual level, as folks pledge to do better by one another, but that’s not enough. Publishers and the companies that own them have to commit to and execute systemic change, which is so much more difficult to conceptualize than a meme because it requires people with privilege to accept that they may have to leverage (or forfeit) that privilege to make it happen. And as cheesy as it is to say that this is what superhero stories are about, it really is what the best ones are about.

Sherif: Totally, it’s systemic.

Your essay features a rigorous analysis of mainstream superhero comics, and their publishers. Do you have any preliminary insights on what The Blue Age might mean outside of those institutions in terms of independent and alternative comics? We’ve seen publishers like Iron Circus really develop and maximise direct-to-reader distribution models with Kickstarter, but there’s also a seemingly constant stream of new, smaller publishers that seem set on trying to break into the Direct Market.

Resha: I want to see other scholars apply the framework to works outside the superhero genre, so I’m really excited to see what other people have to say about what it means for indie and alternative comics. That being said, publishers like Iron Circus and platforms like Kickstarter, both founded (like comiXology) in the late 2000s, are very much Blue Age in my mind. Over the last decade, they’ve facilitated the creation, production, and consumption of comics of a greater variety of genres and forms. These comics are, further, made by a more diverse cohort of creators than mainstream comics. On top of all of that, they provide an alternative to the direct market.

If we have learned absolutely nothing else in the last few months, we should have at least learned that the direct market, and particularly Diamond Comics Distributors’ monopolization of it, is bad for comics. The direct market gets comics to comic book stores, which gets them to a fraction of readers. There are already better means of distribution, but it’s hard for folks to imagine making that change if it means losing the local comic book store.

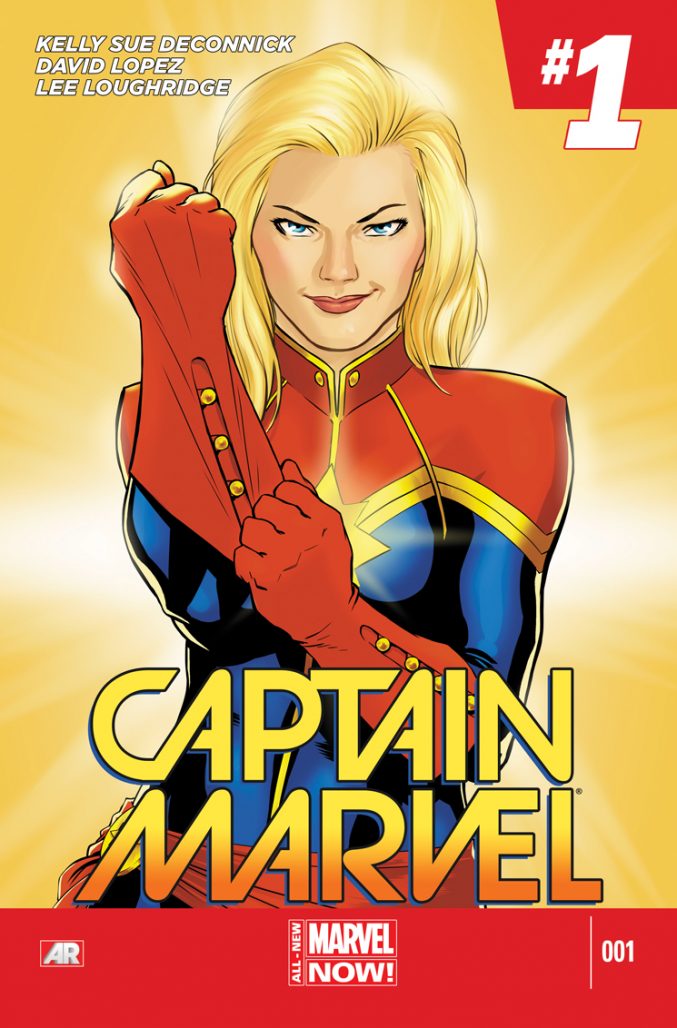

Sherif: How do you weigh up the merits and pitfalls of creator-to-fan marketing? I generally fail to understand why it falls to creators to do this unpaid, extra publicity work, especially for properties over which they have no ownership. But at the same time, those who have managed to successfully establish their personal brands have perhaps been some of the most pivotal Blue Age creators. Is it fair to say that it’s creators like Kelly Sue DeConnick with the Carol Corps, for example, who have really done the work of affective economics which have ushered in the Blue Age? It’s envisaging and targeting that “potential demand” that’s been key, right?

Resha: I hate it. I hate seeing Twitter threads about “how to buy my comics at your local comic book store (and maybe comiXology but please don’t).” The people writing them and making the comics they’re advertising don’t get health insurance through their employers because they’re freelancers. Meanwhile, a publisher can decide to cancel a series based on print sales without really having advertised it.

And it’s not just creators who end up doing free publicity. Comics journalism has suffered because of the ways that publishers have exploited the labor of journalists. It feels like every few weeks there’s a call to improve the state of comics journalism (too often from creators who want critics to be more positive than they already are), but the state of it isn’t a bug, it’s a feature for the industry. Part of the solution for both problems would be to pay people for their labor, but they also require systemic change.

That all having been said, it’s absolutely fair to say that creators like DeConnick are doing the work of affective production not just in the making of their comics but also in the advertising of them. DeConnick went above and beyond to make sure that Carol Danvers appealed to readers and that those readers would know how to get their hands on the comics in which she appeared.

Sherif: Piracy is likewise a subject which surfaces in the comics industry discourse with a certain embittered regularity. How much is piracy a part of the Blue Age, and where do you see that debate heading as far as possible action or resolution? The competitively-priced Shonen Jump Digital Vault initiative is undoubtedly the best incorporation of at least some percentage of the piracy readership into a profitable model.

Resha: I love my Shonen Jump subscription. I’d love to see Marvel Unlimited and DC Universe move closer to something like that, although I doubt either ever will. Piracy is always going to be a problem, and it’s absolutely exacerbated by digital distribution. Digital comics need to be more competitively, which is to say lower, priced: they often cost as much as print despite being valued less by both consumers and producers. Beyond that, I’m not sure how anyone expects readers to be able to assess the value of comics (to know that they are worth paying for) if the industry will not adequately compensate creators for the labor of making them.

Sherif: As you alluded to, we’ve also seen the Direct Market itself become rather shaky during the pandemic, first with Diamond grinding to a halt and most recently DC’s split from them. How do the potential changes to the Direct Market fit within your conceptualisation? Would its downfall necessarily mark a new age, or is there scope for The Blue Age to accommodate this potential paradigm shift?

Resha: There’s a line in “Blue Age” that I wrote two years ago that, over the last few months, has come to feel prophetic: “The Blue Age of comic books is less about dismantling the direct market (the Age that follows may very well be about that) than the recognition of and continued capitalization on nontraditional audiences” who read digital comics even if they don’t read them digitally. What we’re seeing now doesn’t mean the Blue Age is over, and even if the direct market comes to an end, I don’t think its end will mark the start of a new Age because we’ve already seen indie publishers take advantage of alternatives. We’re also seeing traditional book publishers invest in comics in ways and to degrees that they haven’t before. Comics are and always have been more than what’s being published by the mainstream. They are and always have been about more than just superheroes. What will mark the next Age is how we respond to what’s happening now.

Sherif: Finally, one of the strongest observations I feel you make is the idea that representation without access is really just exploitation within the traditional paradigm of Capitalism. I firmly believe representation matters, but it’s also vital to focus on questions of structural access. Escapist media, particularly where it manages to be satisfying, can have the potential to be pacifying. And one lingering concern, despite steps from both publishers on the level of in-text representation, is access at industry level.

Do you feel that the profit incentive will remain the determining factor, if publishers are ever really going to get closer to equality? I wonder if this particular moment we’re living through, of broader engagement with systemic racism as well as the unpacking of cycles of abuse within comics, could lead to the more serious establishment of the moral case for empowering marginalised creators to tell stories – with their authentic voices. A kind of principle rather than the practical, financial concern that has seemingly invariably played a role with publishers to this point.

“Blue Age readers are not content to let publishers exploit them in exchange for representation.” I adore this sentiment. And given the industry’s continuing problems with representation, criticism and access, it’s both profound and re-assuring to see that resolve embedded in such a serious, substantive theory of change as The Blue Age of Comic Books.

Resha: I take issue with the characterization of superhero comics as escapist fiction. They can be, but I prefer to think of them as speculative. They have the capacity to answer the question, “What would the world look like if power was more equitably distributed?” But, you’re right, it isn’t enough to imagine what it would look like in place of making it that way in reality. I think profit is always going to play a role, but I am also hopeful that, going through this moment, publishers will recognize that there is just as much (if not more) value in hiring creators of marginalized identities as there is putting characters like them in the books they publish. And they can’t just hire those creators. They have to support them, they have to make a concerted effort to court the potential readers of these books, and they have to put the principles of the superhero genre to work.

The Blue Age of Comic Books is available to read in the Spring 2020 issue of Inks. To keep up with Adrienne Resha, follow her on Twitter @AdrienneResha