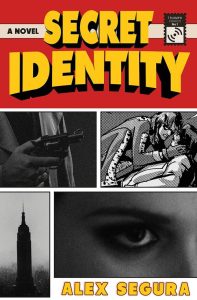

Secret Identity is the new novel by Alex Segura — a murder mystery set amid the comics industry of New York in the 1970s — and it’s an unqualified hit.

Published earlier this year, Segura’s book made the Editor’s Choice section of the New York Times Book Review in March. That same month, a very prestigious comics blog gave it an equally glowing write-up, and now in recent weeks, the novel has landed on many year-end Best Of lists, including NPR’s Books We Love.

Writing for the New York Times, Sarah Lyall called Secret Identity witty and wholly original, with the paper going on to describe it as a “clever homage to classic noir — partly a love letter to New York City in the seamy 1970s, as well as an immersive tutorial in comic-book publishing of that era.” A spot-on way of summing it up.

“People outside of comics who read the book were fascinated because it pulled the curtain back,” Alex Segura says, “and showed you not just what inks they used or how they couriered pages from the letterer to the office, but also what the dynamic was in the office at the time based on my research and the people I spoke to. I think you need the slowburn of fiction to show you that, because you can only accomplish so much just real estate-wise with a couple thousand words on a website. Having readers experience that through [the main character’s] eyes, it at least makes you think about it.”

This novel has certainly captured the attention and praise of folks in the traditional literary world, many of whom had little familiarity with comics going into it, but at the same time, Secret Identity is also the rare prose work that seems likely to be of interest to the vast majority of comics fandom too, or at least to anyone within that fandom with a passing interest in the history of the medium.

There are a few different creative — and practical choices — that make Secret Identity work so well.

The Comics Pages

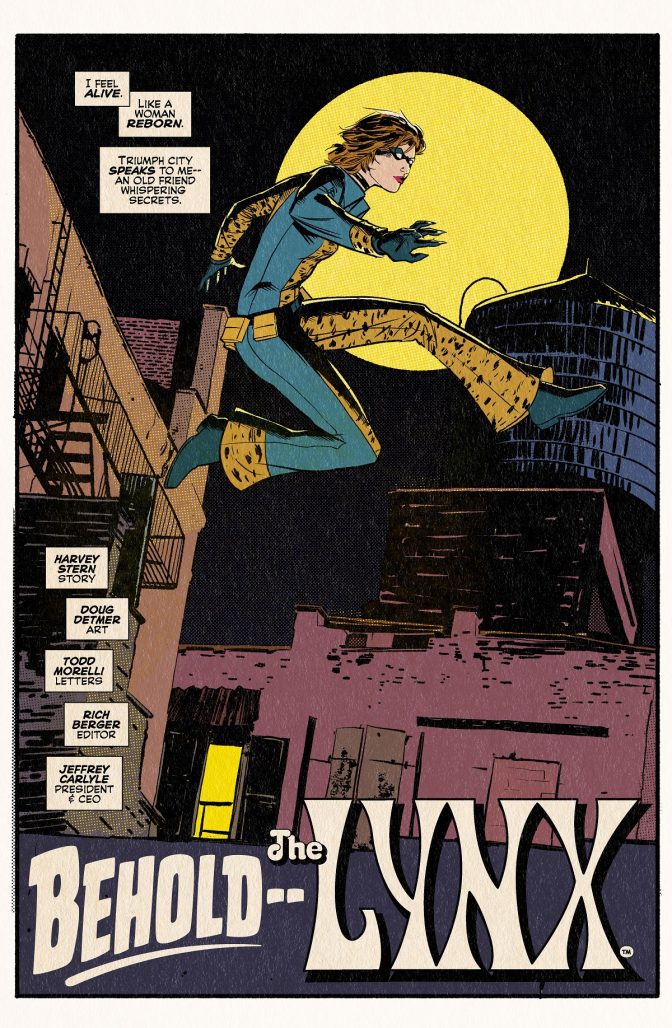

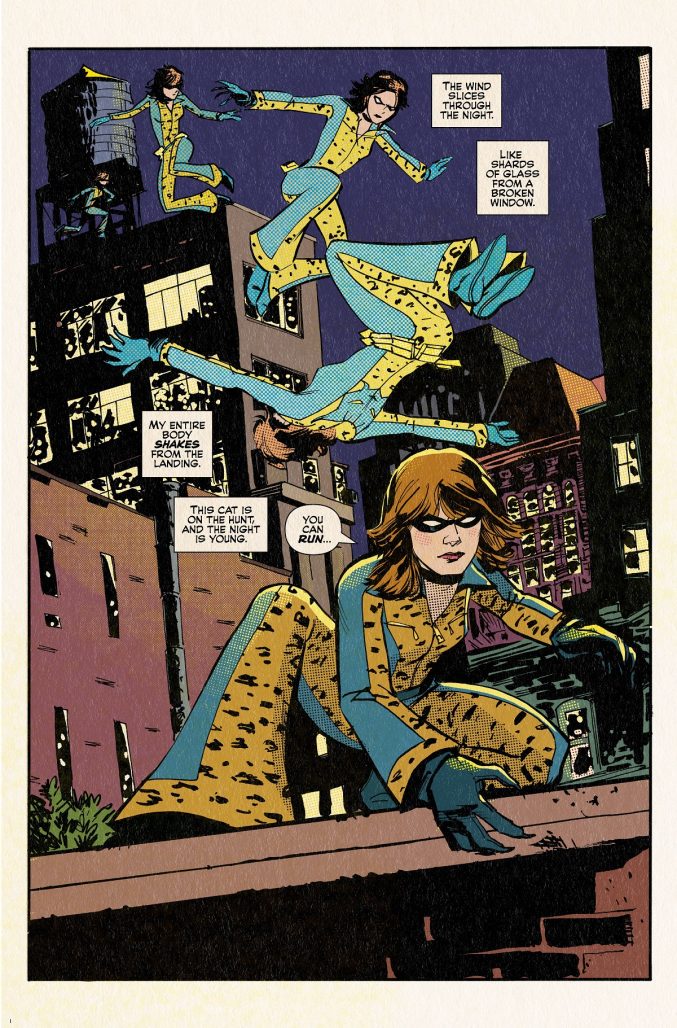

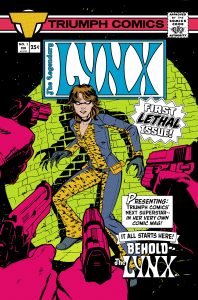

One choice that makes Secret Identity work so well as a novel is that the book is a tight, grounded murder noir as good as any the genre has to offer. It reads well from its first page, possessing interesting characters and an immersive look at a niche industry during a specific (and arguably formative) moment. At the same time, it also deploys a device in which part of its narrative work is done by actual comics art. Artist Sandy Jarrell has illustrated comics pages as if they were the ones mentioned in the novel. These pages are no gimmick, transcending a simple attempt to capture the energy of the ’70s for flare.

No, the comic book art in Secret Identity includes actual details that push the novel’s plot forward, laying a sturdy groundwork that will have seasoned superhero comics readers feeling as if these pages have been plucked from a lost work of the era, as if culled from a full seven-issue run.

The pages add layers to the novel as the novel adds layers to the pages, and through this, Alex Segura and Sandy Jarrell seem to have accomplished something that feels almost unprecedented with this book — using fiction to put readers in the actual comics industry of the time, an achievement that’s equally captivating to people who know little about comics, as well as volunteer writers for blogs like this one, who steep themselves in comics everything.

“When Sandy and I were working on the book, all the work that goes into creating a comics series went into it, you just only got those 14 pages,” Segura says. “I’m not saying we drew seven issues worth, but we definitely had to build the world and create the characters. Sandy did the designs and the costumes, and by the first few pages, I was saying — this is a comic already. We created this comic to serve the novel, but it’s also a comic on its own. So, we’re going to do it as its own thing, and like the Dark Horse Escapist books, it’s going to be very tongue in cheek. These are the lost issues of The Legendary Lynx that Alex, the editor, is compiling, and it’s the work of Harvey Stern and Doug Dettmer, so that’ll be fun too.”

And while Alex Segura could see the vision behind this — being not only a fan of comics, but an industry veteran himself, having worked at Archie, Oni Press, and DC — comic book pages in a mystery novel is a bit unconventional. When it came to selling this novel — Segura’s eighth — to a prose publisher, he knew he needed to do some work in advance so that others could see the vision, too.

“I knew I needed to show proof of concept when I sent the pitch in,” Segura says, “and I knew I wanted Sandy Jarrell to draw it, because not only is he a great artist and underrated and just a pro, he’s a historian too. He knew what I was trying to do. He didn’t try to draw like Frank Miller or Neal Adams or any artist of that era. He very much drew like himself, but he evoked the time period. I wanted him to try to draw like he was just one of the books out at that time, in his style. We got a page that was all set-up and lettered, and that became part of the pitch when my agent shopped it around. We said, this is what it has to be and the comics pages are essential to the story. People have noticed that with the comics pages I tip off things that happen in the novel, and vice versa. That was very much by design. I wanted it to be essential. Once it was pitched as that, I think [Wagman] was able to wrap his head around it.”

The History of the Book, and the History in the book

The book, Segura tells The Beat, was actually a very long time in coming.

Setting the book in the comics industry of the ’70s also pushed Segura to do more — and different — research for this novel, than he had for his other prose work.

“When I realized it was a comic book history murder mystery,” Alex Segura says, “I thought this would be the easiest research I’ve ever done, because it’s all in my DNA. I’ve read Marvel: The Untold Story. I have a whole shelf of books about comics history, which I ended up going through again. Research becomes different when you have an idea about what you’re looking for versus reading as a fan of comics history, someone who is curious about the history of the medium they work in. I read those initially as a fan, and then when I came back to them it was with an agenda. I knew what I wanted to cherry pick from different eras for the novel. I wanted Triumph Comics — which is where Carmen works — to be not a Marvel or DC competitor, but like Quality or Charleston. Atlas is probably the best comp, a company that tries in that space but never manages to. Re-reading those books, I had an eye out for details that could help authenticate the story. Part of the challenge to was that I wasn’t alive at the time. So, I did a lot of research into New York in the ‘70s and also just history.”

One of the most interesting facets of that history was interviews with real-life comics creators who played major roles in the industry during the ’70s.

Secret Identity is rich with composite characters who borrow certain things from real-life people, a bit of Alex Toth here, a little Steve Ditko there, etc. But the people in the book are all fully-realized, original creations. It’s the world and business they kick around in that feels like the one-for-one translation from actual history. The interviews Segura conducted are a big part of the reason for that.

And while the decision to set the book in the industry’s past did necessitate that additional research, it also does a lot of work for the story, helping to shape the world in which the main character exists. Secret Identity is the best kind of historical fiction, the sort that grows right out of the gritty feel of the period in which it is set.

“I knew right away that I wanted it to be in the ‘70s because 1975 is a particularly weird time for comics,” Segura says. “It’s before the direct market starts, and it’s kind of a low point for the industry. Not creatively, but people were wondering if this was going to really work, or if comics was going to go the way of the dodo. It’s cyclical. It always happens. Comics is a medium and will continue in some way, but the mid-70s were a low point. I wanted to show the contrast between today, when we have a Scarlet Witch and Vision show, Moon Knight has a show, Ant-Man has a movie, Peacemaker has a show — there’s a pop culture awareness to a degree we’ve never been ready for.”

Alex Segura on the future of Secret Identity

Alex Segura is not done with the world of Secret Identity after this novel. No, there are plans for a sequel, as well as for full comics that spring from the book, not just the individual pages that readers first got to see.

“We were doing this and wondering, why don’t we just make this a comic too,” Alex Segura says. “We’re going to launch digitally on Zestworld. It’s going to be serialized there, and then the plan is to collect it in print. We’re going to treat it as if these are the actual lost comics we are collecting and remastering and printing for the first time. It’ll have an essay from a noted comic creator — we’re just going to treat this as if it actually happened. We’re basically manifesting this into history, which is kind of a thrill.”

The project is scheduled to launch this month on Zestworld, with the eventual print publisher TBD. Working with Segura and Jarrell on it, will be Grey Allison on colors, Jack Morelli on letters, and Allison M. O’Toole editing. You can find a pair of preview pages from those projects above.

As for the sequel, it will also have comics, only they will be by a different artist and set in an entirely different time period, just like the book itself.

“I went into the series thinking it was going to be a standalone, but then as I wrote it, I realized there’s another side to the coin,” Alex Segura says. “If this book really happened, theoretically, what is the natural second beat? To me, that’s the next book, which is set in the modern day and is about someone who gets hired to work on a relaunch of The Legendary Lynx, but the relaunch is some entertainment company that’s bought the assets. They really want to just print the comic so they can make a TV show. Then, this woman gets hired and she’s burnt out on comics, she’s pivoted to storyboards and movies, but she starts to dig into this character and realizes there’s a sordid backstory. So, it’s the other side of the IP. In real life, someone would have discovered the Lynx and realized there’s value in this IP, let’s buy it and make it into TV or a movie. What if in their efforts to do that, they chose improper means to protect their IP. That’s kind of what happens in the first book, and this is the dark echo.”

Comics Bookcase, formerly a comics blog, is a new monthly column at The Beat.