Imaginary Fiends #1

Imaginary Fiends #1

Writer: Tim Seeley

Artist: Stephen Molnar

Colorist: Quinton Winter

Letterer: Carlos M. Mangual

[Note: This title was provided to us by DC Comics for review in advance of its publication on November 22nd.]

When I was a kid, I didn’t have an imaginary friend. But I was always jealous of my friends who did have them. Imagine: a mythical pal that could do anything and only belonged to you! What more could a selfish only child (at the time, I did get a sister soon after), want? Well, if Imaginary Fiends #1, Tim Seeley’s and Stephen Molnar’s new Vertigo series, is to be believed, perhaps its for the best that my imagination wasn’t active enough to indulge my dreams.

Coming on the heels of Stranger Things 2 and this summer’s film adaptation of Stephen King’s IT, it doesn’t feel accidental that Imaginary Fiends is being released when it is. There’s clearly a hunger for stories like these; horrific tales about young people struggling with atypical living situations while working through the throes of puberty who are haunted by physical manifestations of their worst fears.

I’ll be upfront and say that these types of stories are not typically my thing. Stories in the vein of IT and Stranger Things very overtly evoke a nostalgia for the 80s, when horror stories explored pubescent sexuality in weirdly earnest and honestly sometimes disconcerting ways (see the IT novel’s orgy scene) while teaching us that adults are either dumb or unaware while young people can perceive the world in a way that older people can’t. Now, that said, I like both the latest adaptation of IT and Stranger Things, but I can’t help but feel that stories like these– and I count Imaginary Fiends among them now– speak to the fears of a different, bygone time in our culture.

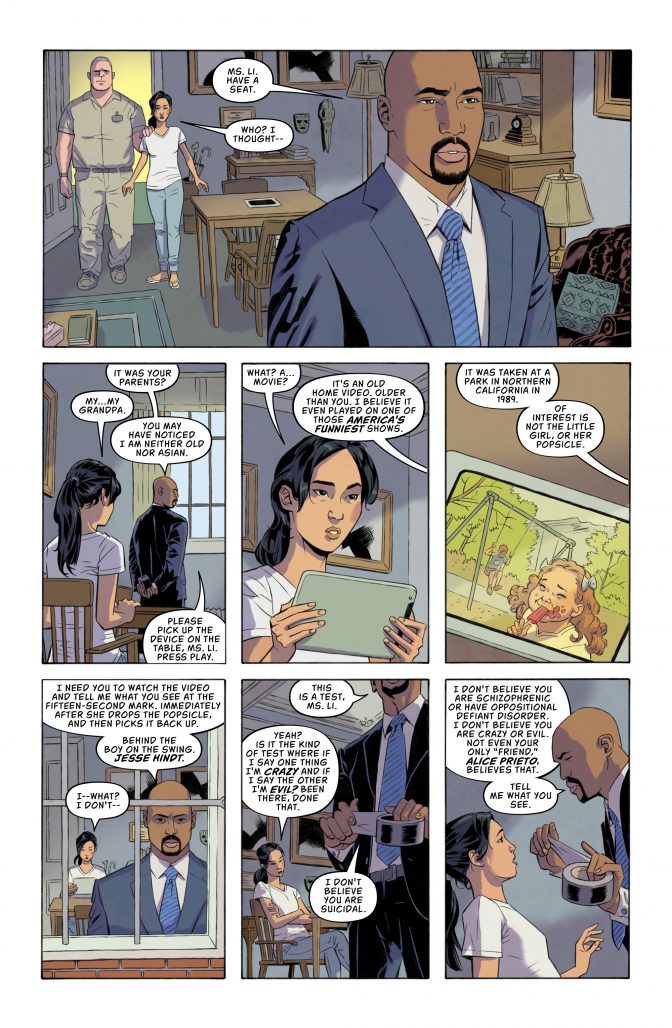

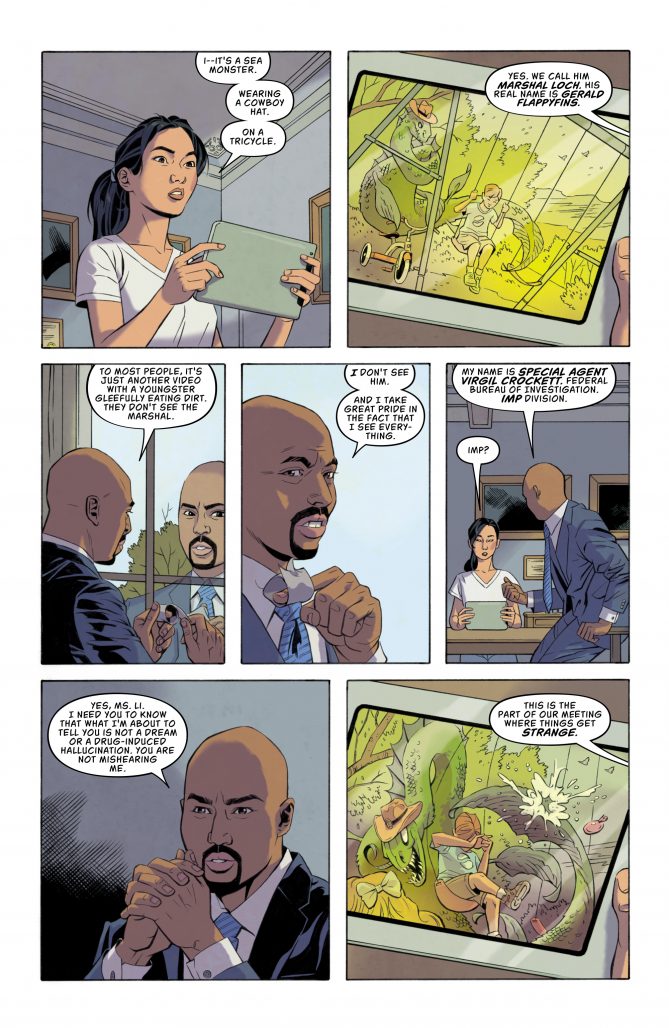

That said, for what it is, Imaginary Fiends executes its attempt at 80s-style horror relatively deftly. The story focuses on Melba Li, a young Asian girl who gets locked away in a mental facility after she attempts to kill her friend, Brinke Calle. She claims she did it on the orders of a “spider girl” named Polly Peachpit, but nobody believes her until FBI Agent Virgil Crockett comes to visit her on her 18th birthday. He reveals the existence of IMPs (Interdimensional Mental Parasites), which are essentially what we in the real world would just call imaginary friends. Except that in their world, sometimes these IMPs go bad and start feeding on their hosts, forcing them to do dangerous things. Most people can’t see these IMPs, but Melba can.

It’s a complicated concept, so most of this first issue ends up being dedicated to setting the stage for the conflict to come. That makes the first half of the story a bit grating to read, as a great deal of the dialogue is as much exposition as it is character establishment. However, what’s presented to us never feels unnecessary to the story– we get a good sense of what Melba’s past was like, what her present problems are, and what the central conflict of the story will be. The best way to put it is to say that Imaginary Fiends #1 is not a bad establishing chapter for the story it’s telling– it’s just a very paint-by-numbers, workman approach.

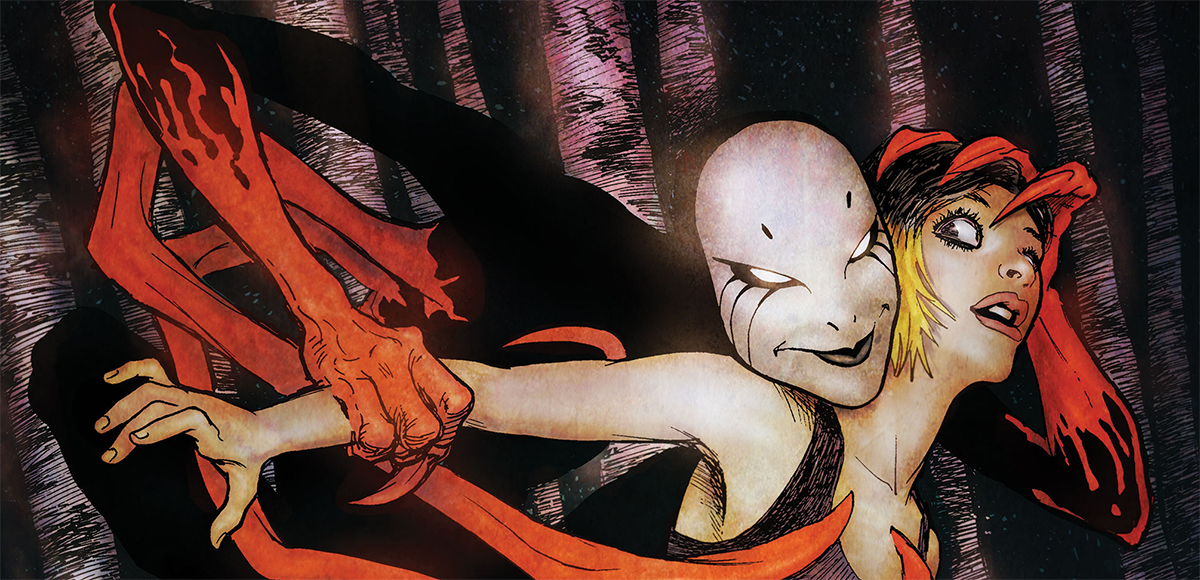

However, that slow pace ultimately does pay off to some extent. There’s a pretty stunning third act turn that sent shivers through my spine when I turned to it. It’s a moment that works primarily thanks to the visuals, which are the highlight of this story. Stephen Molnar and Quinton Winter work well together to establish this very cartoonish look for the world. The start of the story is very easy on the eyes thanks to Molnar’s smooth, unobtrusive linework and Winter’s pastel color palette. And then, at the start of this issue’s third act, the colors shift. The whole affair becomes harsher, darker, and crueler in a subtle shift that pays emotional dividends as we meet another central character to Melba’s story.

But what is Melba’s story, really? That’s the thing I had the toughest time with in Imaginary Fiends #1. Obviously space is limited in a monthly format and there’s a greater story that will be unveiled over the coming months and issues of this book, but the first issue of a monthly comic needs to do the heavy lifting of establishing a character and world that sink their teeth into you and don’t let go. I’m not convinced that happens here thanks to the way that Melba is depicted. She’s very clearly traumatized by her past and it affects her still, seven years on as a young adult, but we see very little of her here besides her trauma. That makes her feel flat. She’s someone who we can sympathize with, but is harder to empathize with. Her trauma is too extreme and too outlandish to connect with most of our own struggles and fears. And thus, there’s little about Melba’s character as presented to us here that’s familiar enough for us to latch onto and want to root for. And that’s troublesome for a horror story with such a personal focus given how much of horror is about creating that direct connection between the story and our emotions.

Besides her trauma, the one other element to Melba’s character that is established here is complicated, troublesome, and opens up a more complicated discussion about Imaginary Fiends as a whole. It’s clear that the book is interested, as so many 80s and 80s-inspired horror stories are, in exploring teenage sexuality. That’s not a bad thing in conceit, but the way it is presented here, primarily through the lens of female characters, feels too general and rooted in tropes to result in some sort of insightful commentary on the subject. There was one moment in particular towards the end of the book that made me particularly uncomfortable about the direction this particular theme might end up going.

So, in the end, is Imaginary Fiends #1 worthwhile? The story as presented, while nothing stellar, is presented competently. It’s a great concept that the creative team does, at least to some extent, recognize the absurdity of; there’s a genuinely hilarious looking imaginary friend depicted in this story. And I’m a big fan of the visual design of this book. But at the same time, the characters and worldbuilding feel more rooted in 80s trope than genuine emotion, which gives me more apprehension than hope about this book’s exploration of young, particularly female, sexuality.

There’s potential for a strong series here, but there’s also strong potential for this book to entirely go off the rails. It’ll take more content to convince me this book is closer to the former than the latter.