This week sees the release of Across the Tracks, a graphic novel written by Alverne Ball illustrated by Stacey Robinson, and published by Megascope/Abrams Books. This non-fiction graphic novel tells of the founding of Greenwood, Oklahoma, a prosperous Black community, and how its business district became “The Black Wall Street” of America. This success story in Jim Crow America did not go unnoticed. From May 31 to June 1, 1921 a white mob murdered 300 Black men, women, and children and razed Greenwood to the ground.

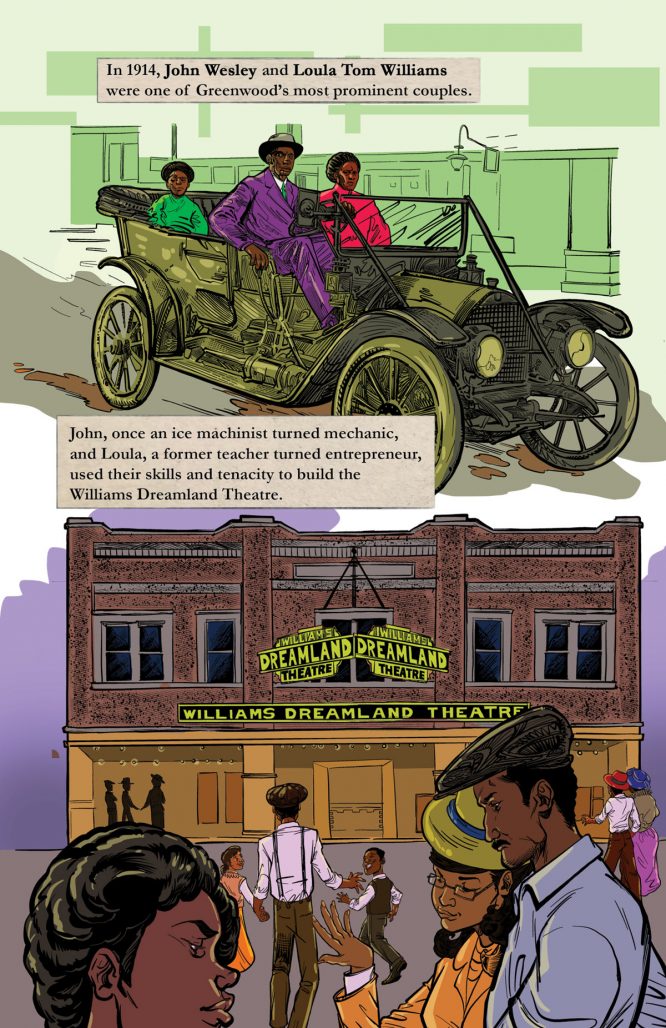

Across the Tracks depicts the Tulsa Race Massacre recently depicted in mainstream TV shows Watchmen and Lovecraft Country. Unlike those previous works, though, Across the Tracks spends most of its 60-some pages on what precipitated the massacre. The book is more concerned with naming the men and women who made Greenwood what it was: O.W. Gurley, John Wesley and Loula Tom Williams, and J.B. Stradford. In this way, Across the Tracks not only personalizes and therefore heightens the tragedy we know will come, but it also reframes that tragedy. Black perseverance and joy take center stage in a way it seldom does when discussing Greenwood. This story is about Greenwood, not Tulsa and the race massacre, a deliberate choice on Ball and Stacey’s end.

The Beat had a lunchtime Zoom call with Ball and Robinson to discuss Across the Tracks, Black spaces, and reimagining one of the darkest chapters in America’s history of violence. [Note: this interview was condensed and edited for length and clarity.]

Rachel A. Davis: So Alverne, in your preface to Across the Tracks, you mentioned how you approached John Jennings about doing a graphic novel on Greenwood. And then you later found out that Stacey emailed him with the same desire the very same day. That is serendipity. What kind of experiences or thoughts led you both to approach John about this project?

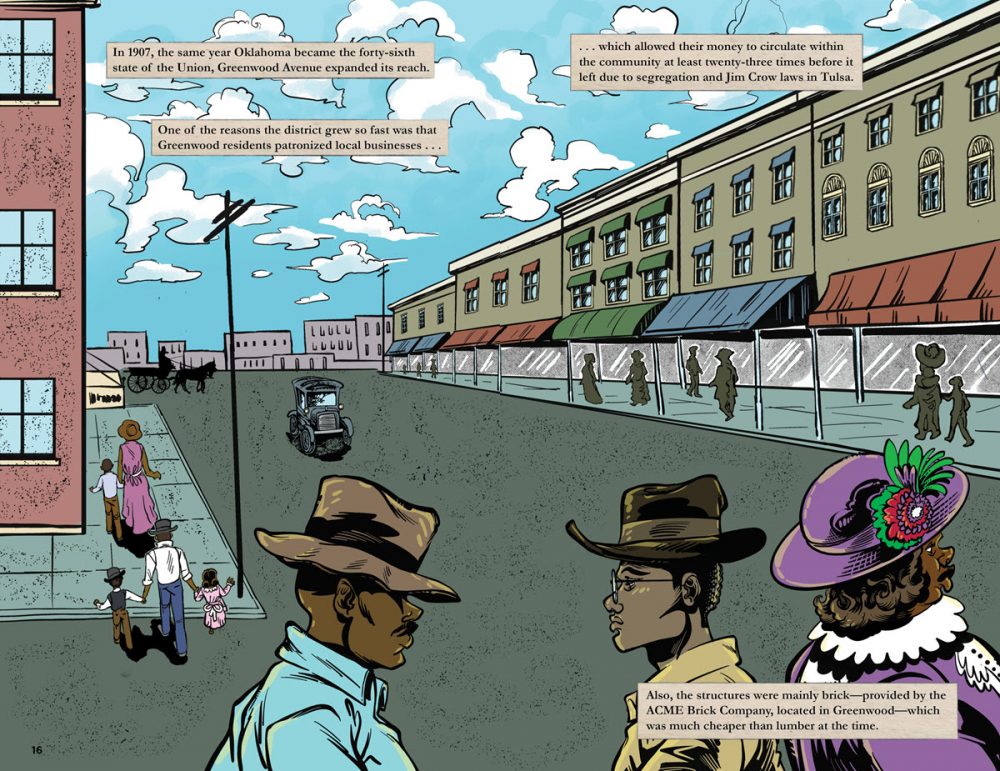

Stacey Robinson: So, my research deals with Black spaces that Black people had agency in, and, you know, these spaces where we were forced into segregation. Just like Jewish communities or Italian communities, many Asian communities, money circulated. We survive, we become self-sufficient, but when Black people do it, our communities are destroyed. So my research looks at places where Black people are actually free at anywhere across the diaspora. And this type of project is perfect.

Initially, I was not the artist slated for this book. When John told me about it, I was like, “Mmm, that sounds like something I want to do.” It was a wicked fast turnaround. So, like, 50-pages of art that you see happened in two months. And it was a lot of fifteen-hour days, it was a lot of going to sleep, taking a nap, waking up at 3 AM. John understands my research. And he knows the type of work that I want to do, and we’re always talking about projects. I literally just talked to him right before jumping on this call with you. So we’re always talking about projects.

Alverne Ball: For me, I love history. It’s something I’ve always loved. And for me, when I approached John, it was a TV show. I was working with some Black producers and directors and a couple creative people. And we’re talking about Greenwood and this thing and we started [and] one day, I got up this treatment for a TV show. And at one point of our friends goes, “You know, this could be a really cool comic.” And then it hit me; I was like, “Oh my god, I have this graphic novel idea.” And I sent it to John, he goes, “You know, we love this stuff.” And he goes, “Stacey already wrote the thing. Would you be interested in writing this thing?” And I was just like, “Wait, wait, are you serious? Yeah.”

And then, just like Stacey, it became this, “We’re gonna need this turned around in this amount of days,” and thought I might have like a week to write this thing, maybe two, maybe a little bit more. And then at the same time, I got COVID, and so I was having these really crazy fever pitches. So it was really anytime I started to feel just a little bit better, I had to get up and write this thing. It was a crazy turnaround for me [with] the script, but I love a good deadline. And so I was like, “Okay, I gotta hit this deadline so we can get this book.”

Robinson: So I know there are some [literary] books coming out this year marking the centennial, but I was actually hoping that there would be more graphic novels, you know? And that was a reason why when John said, ‘Do you want to do it?’ I was like, ‘yeah.’ Now the [original] artist that he had lined up for the book is one of my favorites. He’s a phenomenal artist. I’m like, “Yo, whoa, that book would be crazy” had he done it. But I’m glad that John considered me and asked me if I wanted to do it. I knew if I said I would do it, then it would happen. I knew I was gonna meet the deadline. That’s how dedicated I was going to be to it.

And shoutout to Charles Kochman, the Editorial Director for Abrams, because when John talked to him about [the centennial of the Tulsa Race Riots], you know, from my understanding, he’s like, “We have to do something.” He didn’t have to do that. So shout out to Abrams, and giving John space for Megascope. Some of the illest black-themed stories are jumping off from this Black curated line of books, you know. But shout out to Charles who allowed space for Across the Tracks as well, because literally, it was not in the schedule. So it fit in and just enough time to get this out in time for the centennial. That’s how that happened.

Davis: Absolutely. I mean, shout-out to both of you. Two weeks turnaround and two months for artwork — that’s a very short amount of time for the quality of the book that you have. I’m genuinely impressed that you guys put out such a great product in such a short amount of time, and also with COVID. That’s incredible.

Ball: Yeah, I think that’s the Black folks, you know, rise to the occasion.

Robinson: Yeah, and that’s the thing, too, we have to. Like who else is going to make sure that this history — that we don’t forget this history — was going to make sure that there was a graphic novel K-12 could have in their hands, that educators could? So we got to talk about this subject matter, because the subject matter is now popular culture, right. If you watch the first episode of the Watchmen series on HBO, you watch the ninth episode of Lovecraft Country, both of them deal with Tulsa. Special shout-out to both those episodes because I did a snapshot [of] one of the panels from Lovecraft Country, and I use that for one of the pages on the book. I drew over that, as you know, cuz you got to sample. I believe in sampling and re-mixing and shouting out cultures and people, getting their brain and both those shows got it, right. You know, they deal with our history and then give us hope for the future as well.

Davis: I’m curious what ideas or techniques did you guys use or keep in mind when trying to translate these real-life events for an audience who may not have grown up with the history of Greenwood. How do you adapt that for a non-Black audience?

Ball: For me, I think this might vary by person. For me, it was just like, you think about Black folks, we always hear about the violence of like, what goes on in our communities. But we never hear about some of the joys and some of the achievements in the Spanish establishments that happen in these communities. So for me, I want to show the world this underside of what we see when we talk about the Tulsa Race Massacre. And for me, I wanted to show the faces behind the bricks in the streets and the glamour. I want to show the people not only in the present, but I want to show the people in the past and say that, no matter how much things transcend, some things are still the same.

It’s just, people rise up against adversity, as they always say, you know, pulling up by your bootstraps. Well, this is the perfect example — by your bootstraps and creating this community that was welcoming all folks, really, not just Black folks. But if you go to any Black community, most Black communities are welcoming to all other aspects of ethnicity, when they come into our neighborhoods. We embrace everybody. We know how to bring them in in such a way that we understand what it means to be ostracized.

Robinson: I drew this for Black folks, right. I did not draw this for white folks. Now, that’s not politically correct to say, but it’s the truth. Here’s the thing, I wanted to make sure that we had this history. There are points in the book I was like, “Dang, should we show this? Should we not show this?” This was a conversation we had. These are conversations we have with Alverne, with John, with the publisher. For example, when you look at the cover, you see Black people on the cover, right? Well, when we were designing this cover initially, some of the suggestions did not include Black people on the cover. I pushed back on that, John pushed back on that to somebody. I’m like, “Yeah, we cannot take the Black people off of this book.” Alverne and I [have] got to carry this book, the publisher has to carry it too, right. I gotta go back to the hood, I gotta go back to my people. They’re gonna hold me to a higher standard than the academy and many of my white colleagues, right? But the hood is gonna be like, “Yeah, what you’re doing for us?”

Some people have written reviews and they were like, “Man, we want to see the violence that happens to these Black people.” That was because it was real. Three hundred Black people were murdered overnight. So they murdered them, and then took their belongings and then destroyed their homes. This was very strategic. People want to see that — they don’t want that erased. Here’s the thing with this: Alverne wrote a story that he wrote, so I can’t put in there too much that he did not write. But what you will not see is one muzzle flare in the book. You see Black people defending themselves. You see Black people with guns, right? You don’t see any muzzle flares. [The] reason I didn’t show any muzzle flares is because I wanted any educator, any librarian, any parent who might pick this up at, say, Walmart or Target or in their local library or in a school libraries, I did not want that. I didn’t know if that would be a censoring issue for parents, and I wanted anybody to be able to pick up the book. You don’t need the muzzle flares to understand the history of the book and the history spoken of in a book.

Another thing is, Alverne pissed me off when he wrote this book. I don’t mind saying it because I was hot. There’s one particular line in the book that I was hot about. But when he wrote about it, it was factual information. And it was that the people in the district of Greenwood decided that they were not going to hold hatred in their hearts.

Ball: And how about that?

Robinson: Right? See, I see. Now this [interview] is the first time Alverne and I are talking about this? Right, right, that particular line? And you know, I’ve gotten some pushback, “Oh, man, why did you make a person smiling at the end?” And here’s the thing, this is the fifth book, I think, that I’ve worked on back-to-back-to-back-to-back-to-back [that] there’s been about Black deaths. I know we’re coming up on the centennial. There’s going to be a lot of talking about this and a lot of history and people are going to be upset. We’re coming out of the COVID era and protests last summer that haven’t ended. And we’re going into another long hot summer, right? We have to grab moments of joy.

The Black people who survived [and] rebuilt their community might not be to the same fame that was [before] or the same power as the community that was destroyed just before that. But they did — they did survive. I know there was joy in that moment. I know there was some joy. So I had to show that though I didn’t want to go from, you know, all this Black death and destruction and then leave people like that.

Ball: Oh.

Robinson: Now, I didn’t like Alverne’s line, but it was factual information because it was in a documentary. It was documented. That’s what they did. I drew a person smiling at the end because I wanted us to know that we needed to move on and survive for the future as well. Our ancestors survived for us. I wanted us to understand that we are going to survive this. And we have to have joy going into the future as well. So even though Alverne didn’t write necessarily that person smiling at the end, that was something I had, but I’m prepared for pushback for showing that as well. Because everybody’s not gonna like that.

Ball: And just to piggyback off that, I think you’re so right, but it made so much sense. And the idea of what you’re talking about, Stacey, that, you know, of hope, like, this just didn’t go away. No, Black folks knew about this and talked about it. It got passed down generation to generation. It wasn’t in the history books, but there were a lot of us that knew about it. But then there was a lot of us that didn’t know about it. And I think the idea that’s like, you know, when you think about a Tupac-and-Biggie: that whole summer of confrontation [and] rivalries again. At the end, you listen to that music, and you smile because that music leaves you with that joy.

And that’s kind of, when you talk about that smiling person at the end and that line, it’s like, that’s our joy. Whenever we go through trauma, we find joy in joking about things because that’s how we do it. We laugh — we laugh and cry it out, the joy of the laughter. My biggest thing was not to show one Black body — of Black death — because of what was going on in the summer. Because we just had so much, it was like overkill. you know, to the point where I was like, I want Black people to understand that — and other races to understand this place with the story, but we’re not going to show you the bodies because there’s other mediums that have already shown me the bodies. We don’t need to necessarily show you the body, but we’re going to show you the joy. We’re going to show you the people that came before this so that you understand when you see this loss of property, you understand there’s lots of light behind it.

Davis: I have to admit, coming to Across the Tracks, I wasn’t expecting that ending. When you hear Greenwood, when you hear Tulsa Race Massacre, at least for me, I come in expecting the ending of the story. Because I’ve grown up in a society and in a larger culture that tells me what the ending is: 300 Black dead bodies, planes bombing this Black community. I didn’t expect joy at the end of this book. And it genuinely shocked me. And then I became upset with myself for being shocked. But I was also grateful that these kids that you’re creating this book for, K through 12, they might have a chance now not to be shocked. Have you gotten any children’s reactions so far from this, or what have readers’ reactions been so far to Across the Tracks?

Ball: For me, personally, I have an eight-year-old son, and I have a five-year-old daughter. So sitting down with them and reading this book and showing them [that] this is something I’ve been working on that I’ve kept secret from them. I basically sat down every night and read like a page of the book. And what was great about it was that for me, it was showing the history, showing them other Black folks other than Martin Luther King, other than Malcolm X, and saying, “Look, there are other great heroes that [are] unsung heroes in some ways.” And just showing them that, from the perspective of being biracial, that everything that they teach you about yourself in history isn’t just these two people to the small talents of 10. So for me, it was a great reaction to see my kids ask more about why this person was this.

And then when we got to the violence, of trying to describe what went on, and my son going, “Well, this isn’t right,” but not being horrified to the point where he doesn’t see himself in the world. I think this book gives us the chance to show Black kids especially that they can achieve just about anything. That there’s a place in the world for them, no matter what this country or no matter how cynical this world can be towards them. There is a place, you know, there’s a conduit for them.

We have to be able to stand up and make that that will come true for them, especially in books, because that’s where [it] normally start[s]. I know for me, that’s where it started. And then taking those ideas and those aspirations and taking them from the literary and from the film and every other parts of art and building them out into the real world. Creating those safe havens in our community. You know, I think that’s where we start. I think that’s a reaction from my kids.

Robinson: Yeah, I have not. I haven’t read this to anyone yet. I presented on some of the pages, I’ve shown some of the process pages in many of my lectures and just to show [the] process because I think that’s also a political act. We need more people creating really dope stories and solidifying their intellectual properties. I think that’s a political act. So I show [my students] my process. I did some of that with a few pages of the book, but also not giving away the entire book.

I’m looking forward to some library visits. I’ve already talked to [two librarians] about it, but I want to set up some programming to bring this to the community. But Alverne and I are about to hit a book tour. And you know, it means something because every time we do this, there’s something new that I learn. So I’m thinking Alverne wrote this piece of this, this one particular line, and then I’m upset with him about it. I want to draw this. And he was upset about it, too, right? So there, there are things that we’re learning about with each interview.

Davis: What really struck me about Across the Tracks, too, was how it recontextualizes Black history and the Black experience. The timeline at the beginning and the essay at the end put Greenwood in a global history. Whenever I studied Greenwood, it was always in the context of Black history, maybe American history but specifically Black history. You don’t see the connection to Indigenous or First Nation people. And Stacey, Obsidian Literature and Arts said that your work “speculates futures where Black people are free from colonial influences,” and that kind of struck me as something Across the Tracks is doing — reconceptualizing, reimagining.

Ball: Can I just say that for this book, it wasn’t any speculation. It is exactly what it was. Greenwood existed in Tulsa but was separate from that city in so many ways that it was literally two cities. So for me, it wasn’t even speculation that this was what it was. This is exactly what Black people did. They built their own communities on their side of the tracks, and that was the running theme with Across the Tracks, because I wanted to make the differentiation that everything that was happening in Greenwood was happening in Greenwood. There was no outside influence whatsoever. But when it did come from the outside, it always came at a cost, you know? So, I just want to touch on that because, you know, I’m talking about Stacey making something speculated.

Robinson: No, no, no, no, this is why I had to do this book, right? I’m gonna go back to that because this [Greenwood] was our Wakanda. We’ve had many communities like this, right? So the idea that Black people who can’t unite is just not true. Black people always unite. But every time we unite, there is a government-sponsored destruction, right? Our Black communities are self-sustaining, affluent Black communities. And it’s important that we get this history. So when John talked about this project, I was like, “Yo, I want to do that. That’s the one, I want to do that.” because it’s about research.

So yes, I’m looking at these really fun, Black speculative imaginary spaces. In my research, they [are] the only place where Black people can be free at that I found anywhere on this earth, is in the decolonized Black imagination. Right. And let me give some examples of that. I love to talk about Dr. King’s — Martin Luther King’s mountaintop in the promised land. He said, “I’ve been to the mountaintop, and I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I’ve seen the promised land.” Well, he died right after that. But what he did not give us was the longitude and latitude markers of the promised land or the mountaintop. Our spaces we survive in on this planet, I’ve only found exist inside the decolonized Black imagination. That is the space where it can exist outside of colonial influence. So my work deals with illustrating those, but we’ve also had our very tangible [ones], and I like to call them Wakandas because the Marvel Black Panther movie was an excellent movie. And it gave us a vision that we’re still talking about years later.

Ball: Speaking of, we talked about Indigenous people, that was something doing the research for this book I really wanted to touch on, but I realized that in doing it that can be its own book by itself. But I really wanted to acknowledge that a lot of what this country is built on [is] upon Indigenous peoples’ land. We opened the book up with those Indigenous people because I wanted to acknowledge that they were there first, before Black people and before white people got there, they were there first. I want to acknowledge that, even though I couldn’t tell their story, because, in some ways, I also didn’t feel right trying to tell their story as a Black person, because as a Black person, I needed to tell this Black experience, [but] I at least want to acknowledge that they do have a story there in this history of how Tulsa is made.

Davis: I’m honestly a bit embarrassed to say this, but I never heard of the individuals who helped to found Black Wall Street. I’d never heard of O.W. Burley or J.B. Stradford before this book. I knew about the Massacre, but I didn’t know about the success that precipitated the tragedy. And that made me very sad and made me very grateful for Across the Tracks. Why was it important to name the individuals as well as pleased that they found in Greenwood, and what was that research process like?

Ball: Oh, the research for me was crazy. I’m sure it was just as crazy, Stacey, because a lot of these people, a lot of the images and stuff, don’t exist because everything was destroyed. Massive 100-year-old churches, you know, generations were destroyed in this massacre and this fire. But for me, it became [that] when you look at Lovecraft Country or you look at Watchmen, when anybody starts talking about Greenwood, they always want to talk about the massacre. That’s the action, you know, that’s the thing that gets people excited. But for me, it was like, “So y’all want to see all this Black death.” But I wanted to know the people behind it.

I forgot who it was, but it was somebody from the Greenwood Cultural Center. He goes, “Yeah, we have so many families. Producers are coming down here and trying to buy family rights to create these movies. And the first thing they want to do is talk about the Massacre. Nobody wants to talk about the people that lived here.” And for me, when I heard that, it was a justification, I guess, or it made everything right. It was like, ‘I’m doing the right thing,’ when she said that. It was like, ‘you’re the first person that wants to actually go about people.’ And for me, that was more important.

And so for me, when writing this story, I really wanted to tell people — not only myself but everybody — about the people that created Greenwood. So that when we go back and we look at this we can point to people and go “Okay, this person is this person.” And if you want to do more research about one person or another, you can do that research for me. I cannot lie: Stradford, that dude, man, that was the dude. He just had a vision about Black empowerment. He was the first one of that age, you know, that kind of thing.

Robinson: You know, in reference to the research, there was so much that was destroyed. There are four people in the book I had to make up likenesses for because I could not find them online. And here’s the thing: those likenesses may exist. And just, you know, there might be like one picture of them, for example. And for some people, I could only find one image of them. I’m hoping maybe in the second edition, we can put that in there — that these likenesses were created that we don’t know. I don’t know if that’s important enough, you know, or not, but I wanted to be as accurate as possible. But there was only so much research that I could do while staying afloat to make sure that the book got out on time as well.

So when you look at the tent city, for example, the tent city did not look like that. The tents did not look like that. I wouldn’t change that panel necessarily. I drew a tent city the way that I imagine the tent city looking at some old images, but I did see some other images and the tents did not look like that. I don’t know how important that is in reference to history or not. But in trying to be as accurate as possible, the thing that I had to do was I had to show these people. So then I was like, “Okay, well, how do I want to draw that?” Right? So I tried to make sure that their skin tones were different, right? Like, for example, their ages might look a little different. I don’t necessarily know if that was the right decision or not, but these are the type of things you have to do in order to tell this history. And I may find that once I’m able to go to Tulsa and go research this, I can find a lot more photos, right. So my concern is that I’ve lied on history. And I don’t want to do that. So I’m really, you know, I have my reservations about some of the choices I had to make as well.

You know, so the research was difficult, right? Like, I’m literally researching as I’m drawing this out. I had to look up buses, I had to look up cars. I had to know that car, actually, in this time in Greenwood, this particular car would not exist for another 10 years. But this model of this car did — this particular bus would not have existed here. But the span of Greenwood in a book is over decades, I believe. So it was that level of research that took very long.

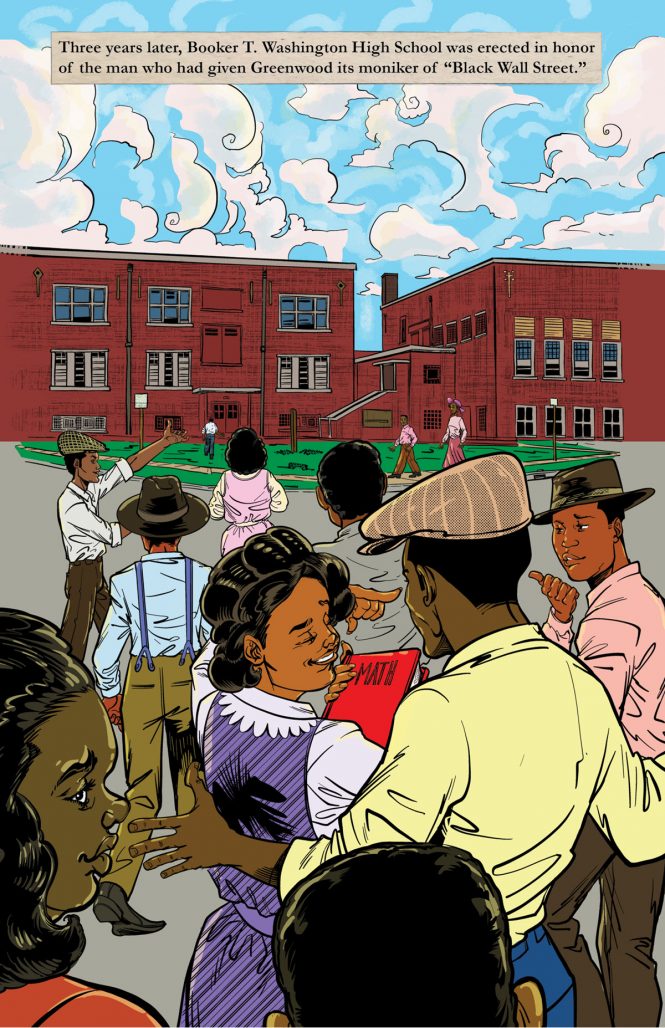

Yeah, there were businesses, some buildings — I didn’t know what the Greenwood library looked like, I looked all over the internet for that and I could not find that. So I had to make up a likeness for that. But whenever I could, I used the photos as [a] reference. For the Booker T. Washington High School, right — that is a photo of the school. Whenever I can use the photo, I used it’ whenever I did not have it, I had to make up a likeness for the integrity of the story. Does that strengthen it? Or does that weaken? Time will tell. Right, the readers will tell us that. My goal in all of that was to do the best job that I could possibly do. And honor the Greenwood community and the descendants of the community and those of us who are living with this history.

Published by Abrams ComicArts under their Megascope imprint, Across the Tracks: Remembering Greenwood, Black Wall Street, and the Tulsa Race Massacre arrives in stores on Tuesday, May 4th.