In what may or may not become a long-standing tradition, Alan Moore has answered questions at Christmas set by the members of a Facebook group called The Really Very Serious Alan Moore Scholars’ Group, who are, as the name might suggest, a bunch of people who are interested in his work. This set of Qs & As were done over the month of December 2016, and in what has also become at least a short-running tradition, we’re presenting them here for a wider audience. You can find a link to the first three groups through the links below, where you’ll also find links to the previous year’s set of Qs & As.

Part II: ‘Julius Schwartz asked me to write his final issues of Superman and Action Comics’

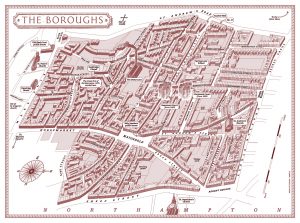

Joe Linton: If a Jerusalem reader tourist wanted to take a walking tour of The Boroughs today, what route/stops/sights would you recommend?

But, if you wanted a more orderly route, I’d advise that you start by arriving at the disastrously re-modelled Castle Station. This was built by the Normans, probably on a pre-existing Saxon structure, and I’d be surprised if this in turn wasn’t located at the site of an earlier Roman river-fort. This is where two of the crusades started out from, and was the castle occupied by Richard the Lionheart and then by his brother, John. This is thus the site of the opening scenes of Shakespeare’s King John, partly demolished by Charles II during the Restoration as revenge for Northampton’s part in his dad’s decapitation.

Exiting the station onto West Bridge you might want to turn right, which is to say roughly west, and then cross over the busy dual carriageway to its south side, where, continuing west, you will find a small opening in the wall that gives access to a sloping downhill path leading down into Foot Meadow. Follow this path along and under the graffiti-daubed railway bridges (this is where Freddy Allen slept while he was alive, and some of the graffiti is that of Dodgem Logic’s delinquent editor Queen Calluz. There’s also a line sprayed up just across the river that’s the work of Bill Drummond) and then continue walking along the riverside for around five minutes until you get to the point where it is crossed by a road-bridge.

Before mounting the steps back to pavement level, check out the space beneath the bridge, with the archaic-looking stonework on the river’s near side bank. This is the site of the Marvellous Mill, where both the industrial revolution and Adam Smith’s ideas of Free Market Capitalism had their origins. Then, when you’ve backed out from under the bridge, climb the aforementioned steps back to road-level, turn left (or roughly north) along the busy dual carriageway of St. Peter’s Way.

While you’re in Marefair, you may as well carry on towards the east. You’ll pass by Hazelrigg House, where Cromwell reputedly slept on the night before Naseby, and then you’ll come to the mouth of Freeschool Street on your right. This, as the name suggests, gave access to the school where James Hervey was educated. This is also the street where the real-life model for Benedict Perrit lived, and just across the street from him was the house where Audrey Vernon staged her repetitive performance of ‘Whispering Grass’.

Looking directly across the road, towards the east and up Gold Street, directly opposite you will see the corner where Vint’s Palace of Varieties used to stand, and where the loiterer in the ‘Modern Times’ chapter would have been smoking his cigarettes and sizing up the local talent. Check out the upper storeys of the buildings on the east side of Horseshoe Street, and you should find the clearly marked billiard hall. Okay, now turn around and go back along Marefair until you’re outside the church and the Black Lion. Cross the partly-pedestrianised street to the other side of Marefair, and down just before you get to St. Andrew’s Road and the railway station you will find a turning on your right that heads off north and is known as Chalk Lane.

Carry on heading north, and having crossed Phoenix Street you will next pass, on your right, the Christ Disciples Faith Ministry. Back in 2006, before some remodelling, this was the day-care nursery where Alma decided to stage her exhibition. Cross over Castle Street, still heading north, and continue down Little Cross Street. On your left, the condemned flats – Fort Place and Moat Place – are what was erected over Fort Street and Moat Street, the former being where the fever cart called for my paternal grandmother Minnie’s first child, also called Minnie, when she succumbed to diphtheria aged around eighteen months. On your right there is the dilapidated west side of St. Peter’s House, the Bath Street flats mentioned in the book as the home address of Marla.

About halfway along Little Cross Street and the west face of St. Peter’s House is where the Destructor would have loomed up (its entrance was in Bath Street, just around the corner). Keep going, crossing over Bath Street – the imaginary Marla’s flat is a little way up, just this side of the central walkway – and continue along Lower Cross Street until you find yourself in Scarletwell Street. Directly across the street is the entrance to Spring Lane School, completely rebuilt since my time there. Look up to your right and to the east, and you will see the hulking ‘Newlife’ tower blocks. Now, cross the street and turn left outside the school, heading down the hill towards St. Andrews Road with the school’s playing fields now on your right.

Scarletwell Street, before the south side was converted into flats, is where Henry George lived. The north side, where the playing fields are now, was where the Friendly Arms once stood, with Newton Pratt’s unusual animal tethered outside and drinking beer. Down at the bottom, where it joins St. Andrew’s Road you will notice the isolated corner house, now divided into two, that features at various points throughout Jerusalem. On the currently grassy expanse of Scarletwell Street’s bottom southernmost corner we have the site of the original scarlet well. Turn right and walk along the little strip of grass on St. Andrew’s Road that stretches between the bottom of Scarletwell Street and the bottom of Spring Lane, and around halfway along is where our terraced house, number seventeen, used to stand. (If you should venture up Spring Lane, past where the fever cart used to be kept halfway up on the right, at the top on the left you will find a splendid emporium called The Vintage Retreat, that serves excellent food and refreshments, and where Joe Brown tells me he found a copy of Warrior #1 for less than a fiver.)

Further along St. Andrew’s Road to the north, on the other side of the road before you reach Spencer Bridge, you will find the Super Sausage overnight lorry park that was at least formerly a hub of the Boroughs’ sex trade. If you liked, you could turn right (and east) at Grafton Street, opposite Spencer Bridge, and go all the way up it until you get to the major traffic junction of Regent Square, at which point you should turn right into the mouth of Sheep Street and wander along it until you reach the round church of the Holy Sepulchre. Carry on down Sheep Street and you’ll find yourself in town centre. At the top of the Drapery, turn left into the Market Square. At the top northeast corner is the site of the Welsh House, which delivered so many people from the blazing market during the Great Fire, while down to the southwest corner in the estate agents that was formerly Alfred Preedy, newsagents, where the childhood dream that opens the book was situated.

Go down narrow Drum Lane, down at this bottom southwest corner, and you’ll find yourself in Mercer’s Row, opposite the taxi rank and the north flank of All Saint’s Church. Cross the road, head east along Mercer’s Row until it meets Wood Hill, heading south. Walking down to the far end of this, turn left and east, and walk along until you can inspect the Guildhall and can see the Archangel Michael with his pool cue up on the roof ridge. Then, turn around, and head back down George’s Row and the south flank of All Saints until you have reached the front of the church, the pillared portico where Audrey Vernon’s parents sat all night after her recital of ‘Whispering Grass’. Across the road you will see the mouth of Gold Street, with the jewellers to the left where Ann Timson saw off three sledge-hammer wielding robbers with her handbag a few years ago. I’m sure this incident is available on Youtube, and is always good for an admiring laugh. Head down Gold Street, back along Marefair and past St. Peter’s Church, and you’re back at the station again. You’ve now seen pretty much everything and can go home. If you want to check out some of the more outlying sites of interest, like St. Andrew’s Hospital or Kingsthorpe Cemetery, then I suggest you buy an A-Z and find them yourself. I think my work here is done.

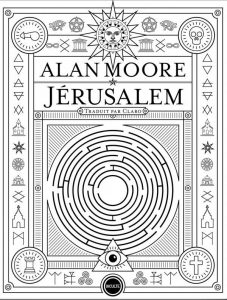

Flavio Pessanha: – In 2017 Jerusalem will be published in Portuguese. What do you think is/are the most important issue(s) translators have to deal with when translating a book like Jerusalem?

When I wrote the material originally, I was relying upon trust in myself and my own processes, as any creator must. When a translator recreates that material in a new language, they are effectively becoming the author of a new piece of work and they should likewise place their trust in themselves and their own processes. By doing so, they are serving the work to the best of their abilities, which is all that I was ever interested in doing, and they will also be delivering the new text straight from the heart, which is the manner in which it was originally intended to be transmitted.

I’d also add that it’s probably important that anyone translating my work should try to have as much fun as I had with the original composition. I acknowledge that translating my work is probably very, very difficult at times, but I hope that the process has at least some enjoyable rewards, and is never a dispiriting chore. Other than that, just keep doing what you’re doing, and know that you and your efforts are profoundly appreciated.