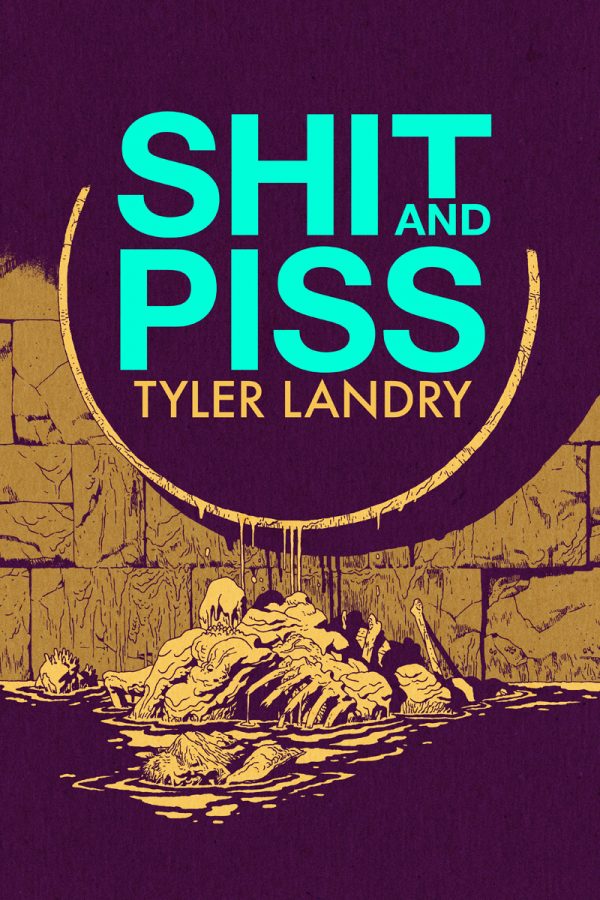

Imagine the comic that not only lives up to that title, but manages to do so with a poetic grace. That’s what Landry has achieved, a post-apocalyptic meditation on the relationship between life and filth, with death and violence as crucial to the cycle of life. Taking place mostly inside a sewage system, Landry offers a guidebook to the grotesque muck that congregates and forms within the tunnels, moving life to its next level with a primeval urgency. Humanoids that appear half-finished or riddled with pustules or made to consume and dispose populate the sewage with a truly disgusting vibrancy, thanks to Landry’s emotional renderings that drench you in the filth he portrays. You aren’t just reading about it — Landry’s skill is such that you are there, surrounded and terrified. And if this is a guidebook, it’s one that unfolds with poetry, directly placing humanity at the center of the putrefaction, dragging us back down to our origins and suggesting that the primordial and the apocalyptic are sometimes impossible to separate. Everything is a creation of the muck.

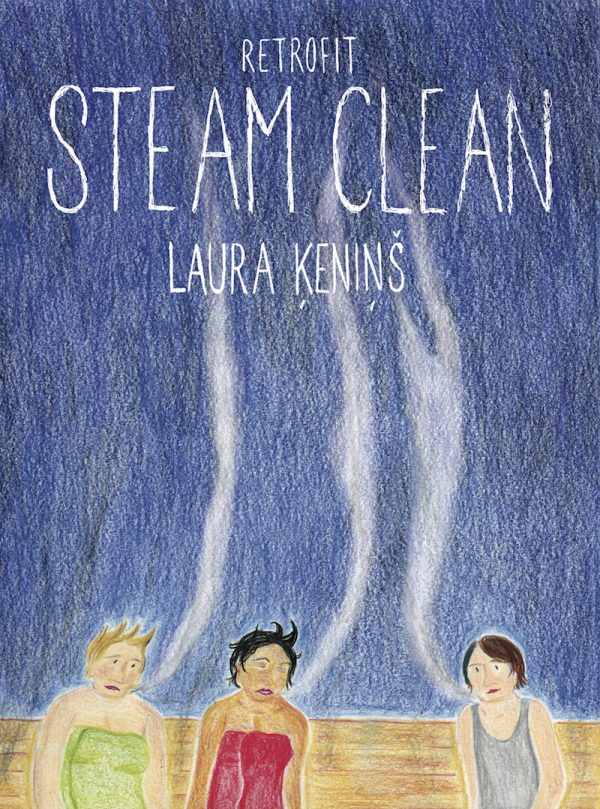

Kenins’ beautiful color work brightens a pretty heady conceptual piece that shoots out tension that could actually become overwhelming with a different visual presence, but remains something digestible. That’s important, at least to me, because as a straight white old guy, this is the sort of comic that makes me feel like I’ve been invited into something that I usually wouldn’t be part of, but I’m talking about the experience in public and that can often demand a delicate approach. Kenins depicts a party for queer women in a sauna and, as the title suggests, this is a cleansing ritual for them where they air out their personal concerns within a political context, frequently illustrating the collisions that are inherent in that dynamic. Each character feels like a representative for a common situation, including a woman rebuffs demands that she pronounce a problematic sexual encounter as assault and a transitioning transgender person who is current non-binary and is convinced their presence is not welcome in the steam room, as well as a character of embodied symbolism touching on the pure American moral ideal and the misunderstandings of human nature by those who embrace that ideal. What I liked best about this is Kenins’ defiant non-judgmental presentation, a true feat in this highly-charged, political era. Each character’s story and attitude is approached with sympathy and the suggestion that you lend them your ear and empathy, that you take your own experience outside of how you react to theirs, and really ruminate on how political and social arguments seem so simple in solitude, but sometimes collide against people’s real lives once the discussions begin.

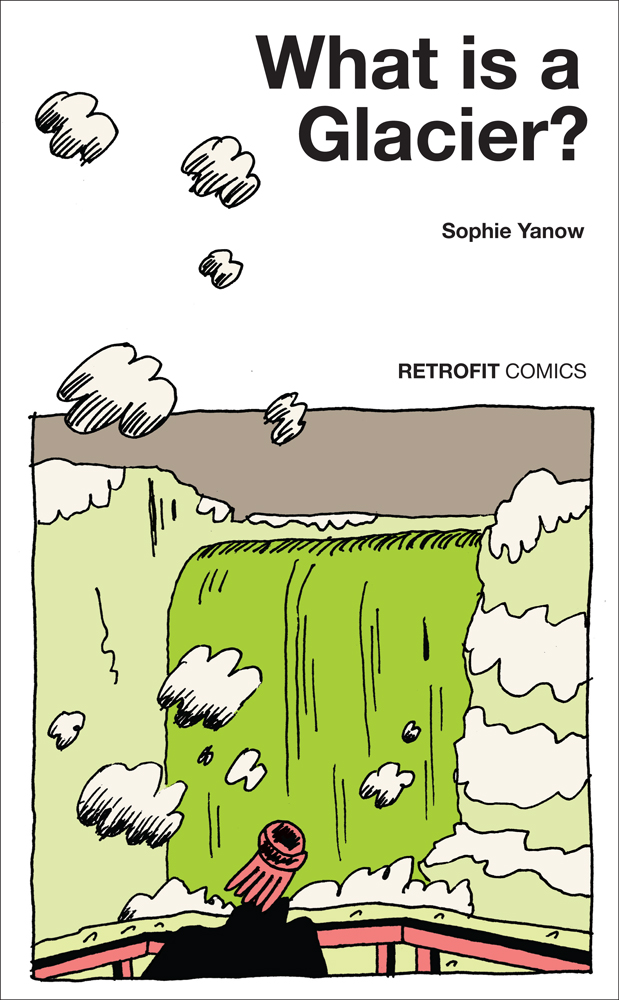

What Is A Glacier? by Sophie Yanow

Unexpectedly, I found a couple things I identified with in this sprawling rumination about human impact, specifically being flagged as a immigration risk when entering Canada and being troubled about tourism in Iceland even as I was enthralled by my own experience there. These are actually two circumstances that get to the heart of what this book is about — the honest enthusiasm of humans as a destructive force in the world. People go to Iceland out of pure curiosity, out of the desire to experience natural wonder and perhaps even a culture that they see as elevated or pure in some ways, but its the onslaught of that affection that has an impact on the object itself. Yanow wraps this around examples of apocalyptic thinking and even practical versions in the face of disaster, as with her father’s wonderful rationalization for not wanting to reinforce their house to survive an earthquake — because the house will just slide into the creek if an earthquake hit. Yanow is concerned climate change will beat the big earthquake to the punch, though, and apocalyptic thinking piles on top of one another, winding through a recounting of a doomed romantic relationship and a realization that we are all looking at the end in our own way on multiple scales — you’d think we’d be used to now that it’s on a global one.