The noir genre has one dynamic at its center that repeats so often it’s hard to tell if it’s a cliche or an archetype — a man searching for something more in life encounters a woman who brings danger and mystery. And at heart, that is all Tumult is about. But though it draws thematically from creators like Alfred Hitchcock and numerous others, its innovation involves putting the man in similar psychological ground as the woman involved. Neither have steady footing and it becomes the readers’ job to decipher which one is actually worse off — the woman who is slave to her psychological condition and other outward manipulations, or the man, who’s just a shitty, self-destructive loser?

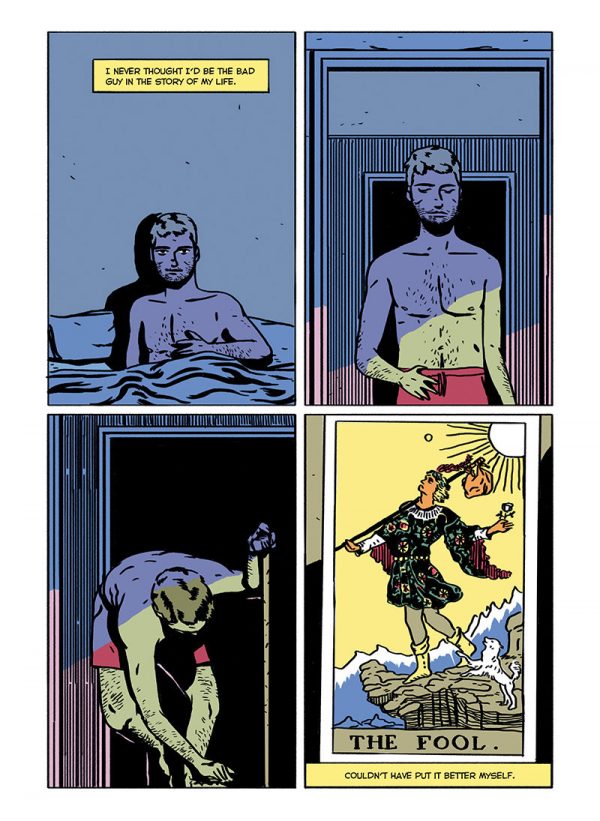

Adam Whistler seems to have it all, just not as much as it takes to make him a superstar. He’s a working commercial and music video director in a nice relationship with a nice woman, having a nice time on a nice vacation. Adam decides to throw that all away for no real reason in particular other than it isn’t enough to make him feel anything. The impact of all the affectations of his life needs to hit harder for them to mean anything to him.

That’s where the woman comes in.

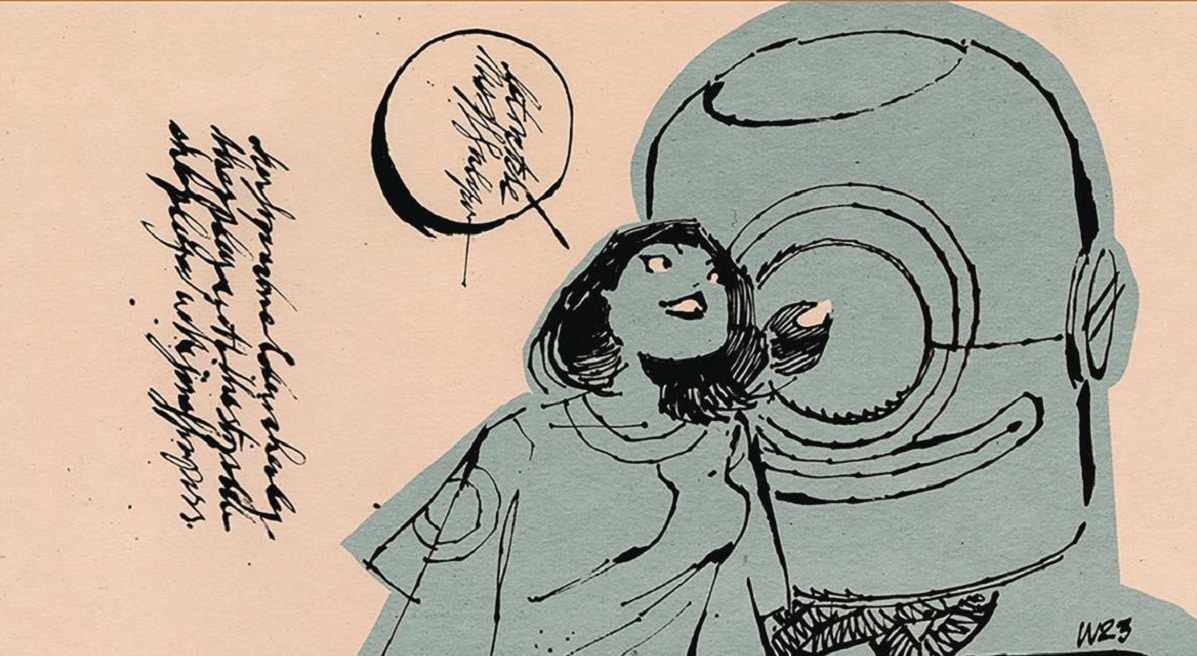

But first, there’s the fact that Adam is spending all his time during free fall with his old friend Marek, another male sleepwalking through life and blaming it on life’s inability to be very fetching. The center of Marek’s work is a film criticism series where he analyzes the movies of their formative years in terms of expressing manhood. Writer John Harris Dunning includes some of these analyses and peppers his story with reminiscences of the same — self-deprecating anecdotes about emasculating missteps during Dungeons and Dragons games or reminders about just how much Kurt Cobain loathed himself into a shell. The woman is the first chance Adam finds to actually become a man as he understands it.

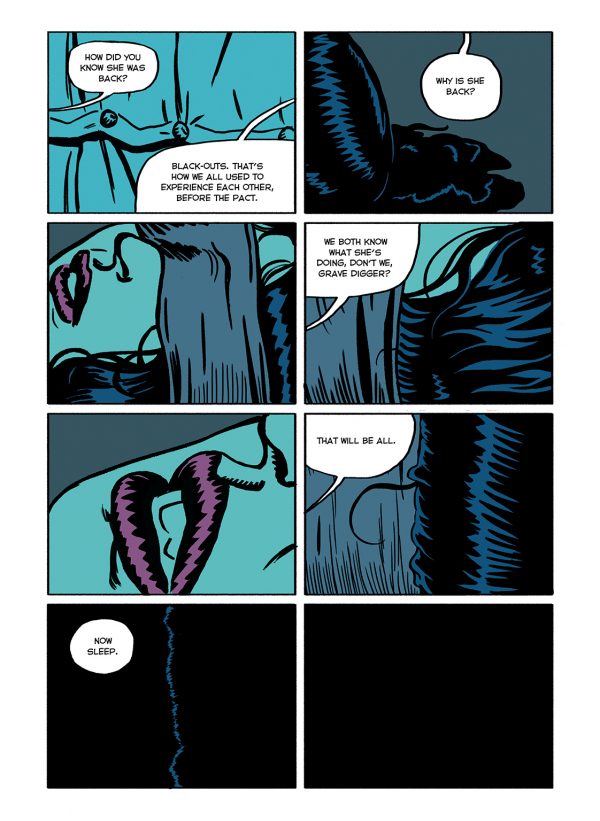

That woman is Morgan. At least initially. The mystery of Morgan is that Adam doesn’t know who she is and then thinks he’s on the path to knowing and then thinks he knows, but we all understand that he doesn’t. In fact, though Adam casts himself as much more important, he is really the sidekick in Morgan’s adventure, which we, though Adam, are allowed to encounter the edges of, dipping our feet in when Adam manages to make some impact on it. But while Adam focuses on the lessons of Predator and Rocky in what it means to be a man, he’s being led along in his own fantasy that he is actually having his own adventure.

Dunning’s script is personable and dark, and as it borrows pieces of the noir genre and mixes them up with good old paranoiac conspiracy storylines with good, sarcastic humor and the ability to laugh at darkness. What pushes it over to something more intriguing though is Michael Kennedy’s artwork, which takes the psychological conditions of the story’s two principals and uses them to wash through the visual presentation as something that has no anchor. The expansive color distortions, in particular, makes this a surreal journey, with washes colliding to create discolored reality — purples against greens, lavender fighting with pink — a stark, pop art-style comic book color scheme announcing that something is not right here.

But the colors are only the atmosphere through which Adam walks — his inner world is just as skewed. Like many men, he approaches women as puzzles to be solved and reward the man with transformation. Neither turns out to be true and Adams is doomed to stumble through a discolored reality he never really perceives clearly.

This so looks very nice, and a bunch of SelfMadeHero books – including Tumult – has just been added to Comixology. Yay!

Comments are closed.