I feel like over the last decade, the travel graphic novel has become crowded with pedestrian work. The form has taken on the role of rite of passage for young cartoonists who are interested in non-fiction work and decide to plan travels around a creative cartooning purpose. It’s not that I think they shouldn’t pursue these projects for themselves, but I’m at a point where I find they don’t often have much original to offer the reader, and sometimes it’s like reading the work of someone going through the learning process. Many of the territories chosen are often well-trod, and many of the details are new to the traveler but well-documented to those of us in the armchair. Speckled with the interpersonal dramas of millennials traveling together and I’ve sort of lost partial interest in the genre.

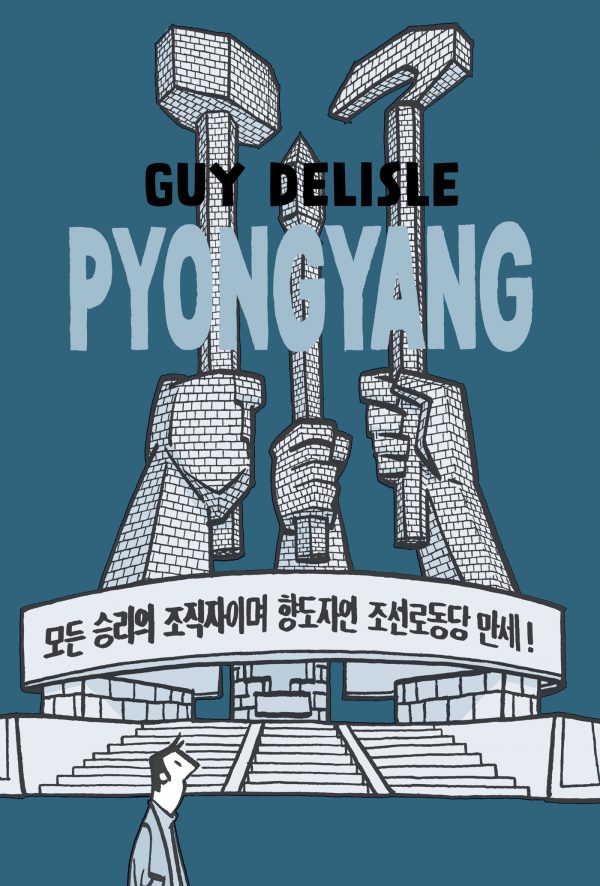

But like an antidote to this ennui, Drawn and Quarterly has reissued a pioneering class in the modern form, though, and as a showcase for what makes Guy Delisle’s work different from others — and therefore a master class in the form — Pyongyang is practically perfect. That he is able to portray an experience in a country that’s still obscure since the books original 2005 release, and that his observations are still valid in 2018, is a shining bonus.

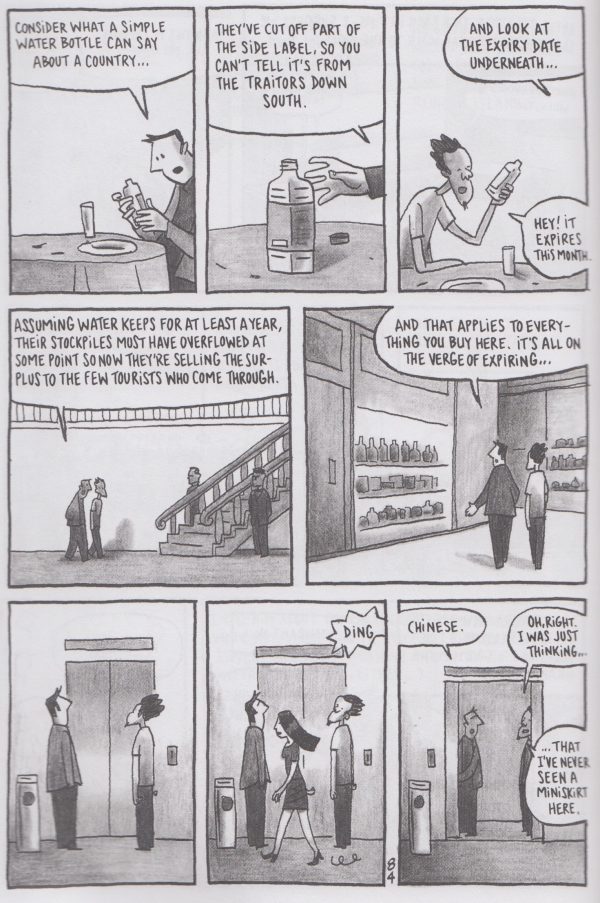

And so this modern dystopia, through the lens of the visitor, ends up being less an oppressive hell and more a surrealistic limbo. A place to wait around. A place where little happens, where time stands still, where drama and action are hidden from view and the visitor is forced to endure the passing of air as the only indication of temporal movement. A place where culture has been replaced by a meticulously-crafted feel-good edifice that hints at something sinister, but offers only absurdity, much like Disney World. The city of Pyongyang comes off like the world’s most blank theme park.

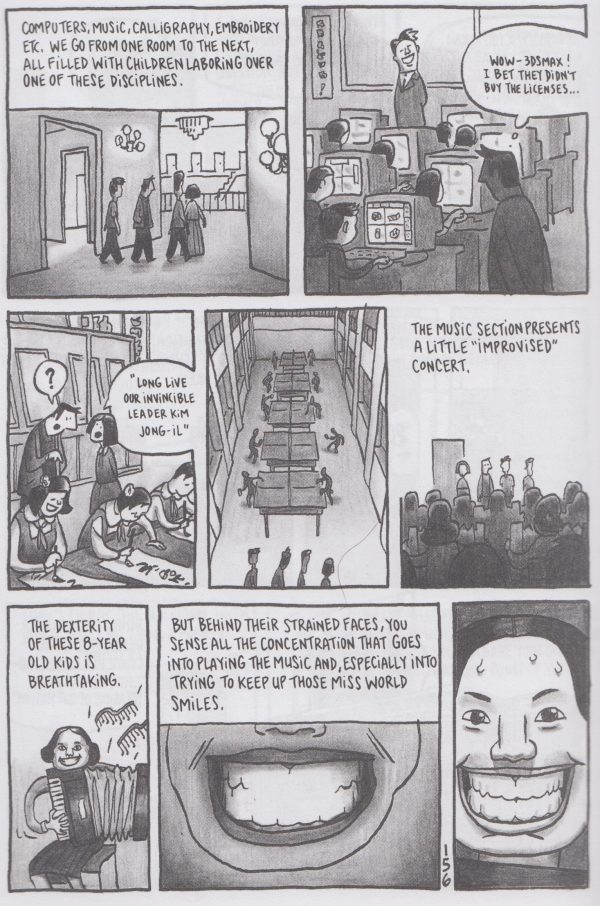

That’s one of the major differences between this work of Delisle’s and so many travel memoirs. Most locations are chosen because of the richness of culture that invites the cartoonist to dive in. North Korea is almost devoid of culture, to the degree that there seems to be a giant vacuum sucking it out of the atmosphere in order to keep visitors from discovering it. Culture is something to be unearthed, and even then, only flakes of it survive. A travelogue about North Korea is an investigation of what has been abducted from perception.

Delisle’s life in North Korea as an animator becomes a swirl of empty and emotionless encounters with the stale bravado of its leadership, always accompanied, hardly ever alone. Everywhere he goes there is a reminder of not only leadership, but the love of leadership, and there’s hardly a second to contemplate much. The so-called “dear leader,” at the time Kim Jung Il, both his appearance and his words of guidance, are an inescapable a fixture in North Korean daily life. You see him more than you see Coke cans and slogans in America. No wonder Trump loves the North Korean dictators so much. They’ve escalated pathetic needling to a grandiose scale. Their way of cornering the citizens and demanding love is exactly what Trump wants out of America.

Delisle’s only respite from this strange, septic world is through the intermingling of other international expats in hotel bars and foreigner-only restaurants, which creates a dynamic a lot like a surrealist stage play where a bunch of people wake up in a strange room and don’t know how they got there, so act out their own indulgences as per the playwright’s whims.

Delisle’s visit unfolds with a wicked humor winding through it, which comes from both the cartoonist’s coping mechanism in being in the country and his narrative solution to making such a dour location enjoyable. But it also hints at the problem outsiders have in piercing the country itself. Actual communication becomes like banging your head against a wall, so impenetrable is the culture and so curated the experience of visiting the country, and a visitor, whether physical or literary, is just going to end up talking to themselves when no helpful answer comes from the citizens.

That tells us as much about what we’re up against in finding common ground with North Koreans as we are in doing so with each other. As the political divide becomes fierce in our own country, with competing versions of what constitutes reality and at least one political party moving dangerously into a cult of personality, Delisle’s depiction of a real-world dystopia should chill us to the bone.

In our world, the most successful dystopia is one of absurdity, filled with forced smiles and happy sounds that drown out the distress, forcing it to remain unacknowledged, with the people devoting their energies to applauding an emperor who, as usual, forgoes the clothing because he knows no one will say a word about it, no matter what.

It doesn’t just take fear to get people into that dystopic groove. It mostly requires a lot of perseverance, which most potential dictators have. The people will often do the rest, and Delisle understands that.

rather like North Korea, Comicsbeat is big on censorship

I’ve read only one, more recently published Delisle book, that recounted a kidnapping in Chechnya. Seriously good, and it had ‘from the writer of Pyongyang’ blurb on the cover/backmatter. Always up for a small story within a place, that’s informed and can create a sense of it. Put it alongside others, and read it with a critical-awareness as one source. Better to read if the form is good, like I’ve found Delisle’s to be.

I would put PYONGYANG way up there in my “must read, taught me a lot about something real” list along with PERSEPOLIS and MAUS and AMERICAN BORN CHINESE. It’s a pretty revelatory work in my mind, among the best that comics as a form can be.

-B

“Revelatory work”, yeah, it reveals a lot about the writer. Not so much about the country.

Comments are closed.