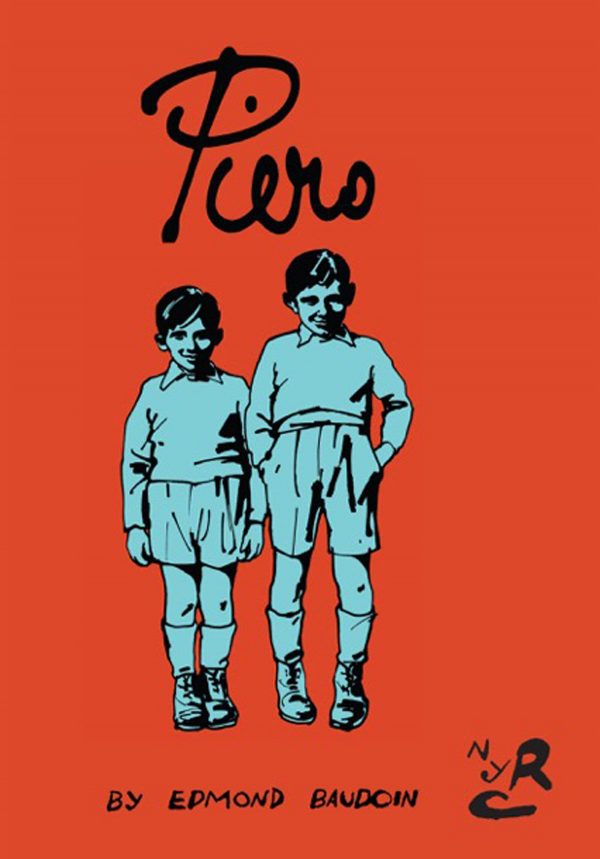

Edmond Baudoin is a relatively obscure figure in America, looming under whatever radar we have that detects French cartoonists. As explained in Matt Madden’s excellent introduction to Piero — Madden also did the translation of the story — Baudoin specialized in autobiography and was really an early and important practitioner of that form in French comics in the 1980s. His influence wouldn’t reveal itself until the 1990s.

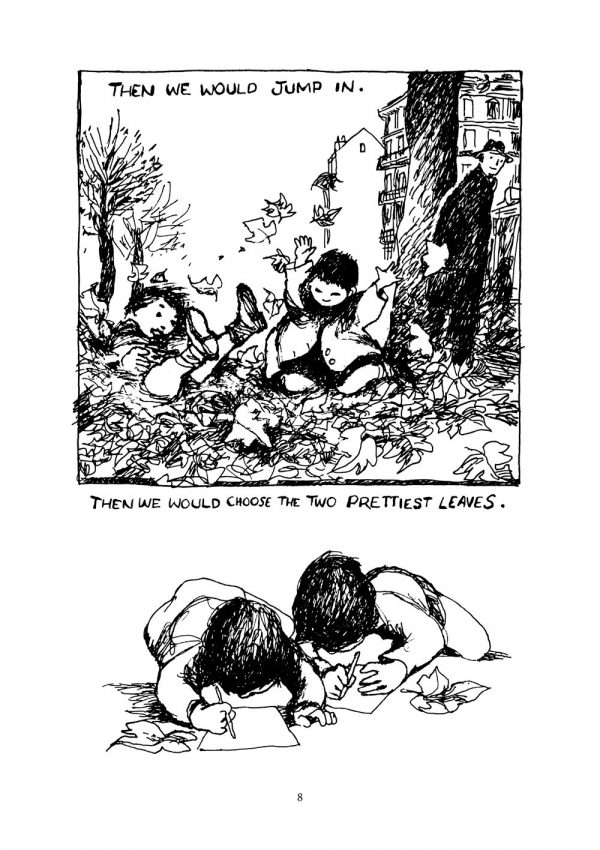

Piero begins as Baudoin’s remembrance of he and his brother’s childhood together in Nice, capturing the freewheeling quality of their preschool life and focusing on their love of drawing. His brother Piero is sickly and this causes them to have a lot of time alone together, and also delays Piero’s school so, despite the age difference of a year, they start at the same time.

The memoir ambles along with a sweet, bucolic quality that finds the moments of everyday life displaced by the boys’ flights of fancy, as when they encounter a crashed flying saucer that requires dreams for fuel. The alien convinces Piero to help him and then takes away his memory of the event, but Baudoin has captured the entire encounter in their shared sketchbook. Is this fantasy or did it really happen? I think the answer is both — while we technically understand it as fantasy, the boys’ imaginations are so vivid and the stories that unfold so all-encompassing that it takes on the intensity of reality. And that’s not the only time it happens in the book.

Baudoin is able to directly link their imaginative play with the work they put down on paper and in one charming scene reenacts a drawing game the brothers played. Using a big piece of paper, each would draw a castle on one side, and then proceed to draw a battle between the two sides, eventually cramming the paper with soldiers and cadavers until the point that the page is impossible to decipher. Baudoin offers a step-by-step visualization of what might appear on the paper, and it’s as vivid and exciting as I imagine the real game was for the two boys.

If this qualifies as a tale of growing up, it’s one that the act of creating becomes imperative to develop a view of the world. And if in so many stories there is some kind of moment where the kids learn that the world of adults is not so infallible, causing doubt and angst, the equivalent in Baudoin’s experience is the moment he begins to compare newsprint photos with his own drawings and realizes that the photos are just manipulations. To look closer at them is to see them break apart, and Baudoin begins to use them as a guide for his own work, as a way to measure when his own drawings cease to be representative of the world in concrete terms. This transforms into a way to differentiate between the way he and his brother not only see reality but express it.

Art, as Baudoin’s memoir continues, becomes the lens through which the world unfolds, and certain encounters with certain art become expansive to his experience and also encourage analysis of what the representations mean, and how they relate to his own work. In this way, Baudoin’s recounting of growing up becomes a document about how he learned to look at the world and see beyond what was in front of him, all through art.

But it’s also a manifesto of sorts, a proclamation that one of his family, either he or his brother, was required to devote himself to art. It turned out to be him after a strange twist of emotion, but his brother turned out to be crucial not only to his evolution but to his realization. Art is not achieved alone and artists are not islands. Baudoin understands that and explains it to us all with this gentle reminder of a memoir.

Comments are closed.