by Alex Dueben

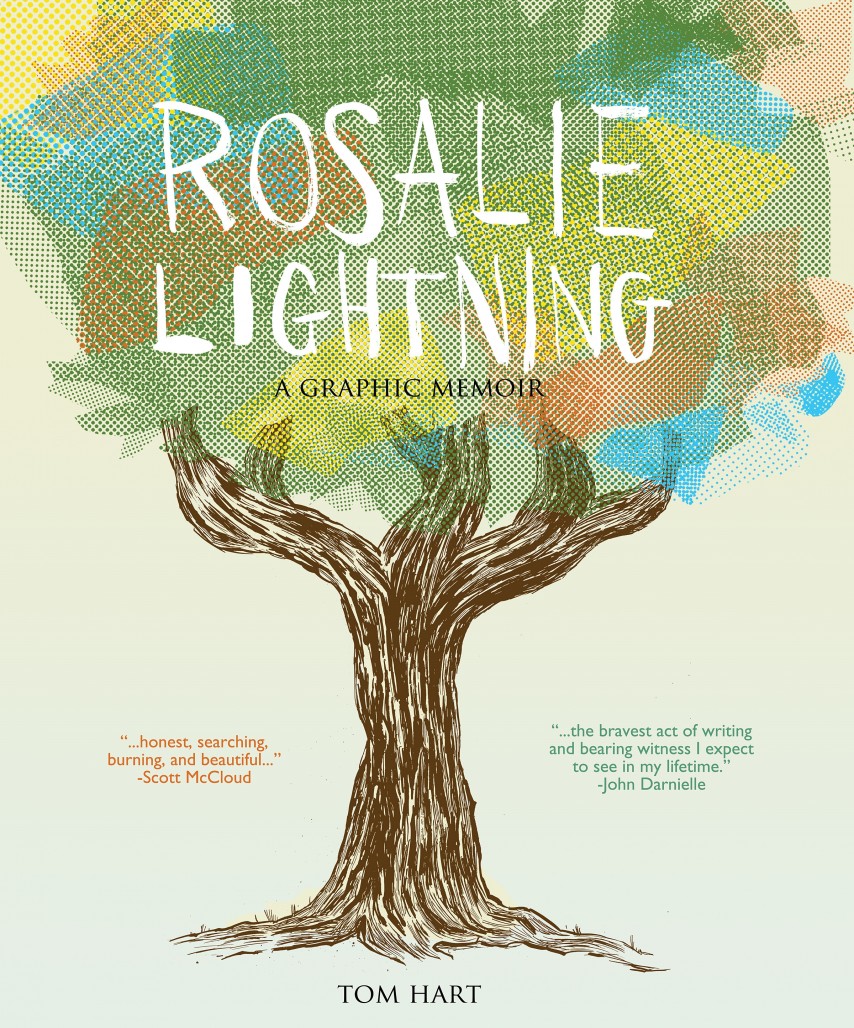

Tom Hart is a cartoonist and teacher best known for Hutch Owen, a series of satirical and socially intelligent comics. He is the founder of The Sequential Artists Workshop (SAW) in Gainesville, Florida, and before that taught at the School of Visual Arts for many years. His new book–possibly his best book–is Rosalie Lightning.

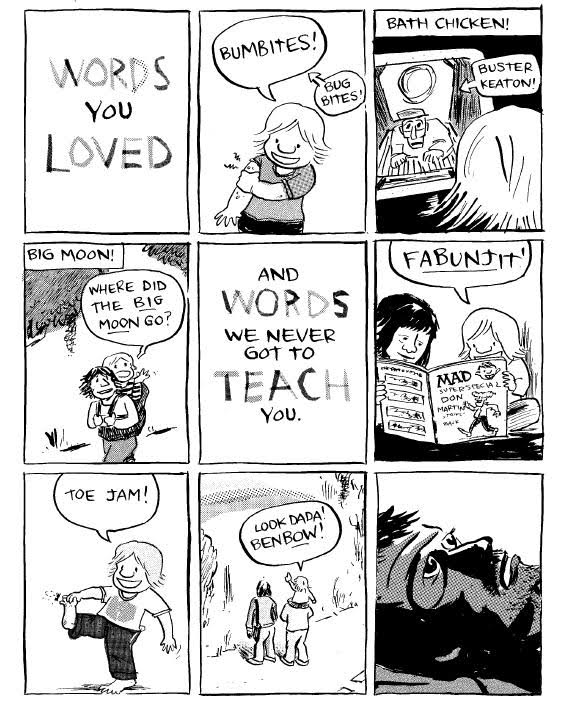

It details every parent’s worst nightmare, the death of his young daughter. The book details dealing with grief, remembering Rosalie, and finding a way to go on. Tom was kind enough to talk to us about creating rituals for life, and how the worst period of his life led to the publication of this singular artistic creation.

Alex Dueben: How soon after Rosalie’s death did you begin to record your thoughts and feelings about what had happened?

Tom Hart: Well, it started when this happened because I’ve always written and drawn and I’ve always made books. That process has been the main way I’ve dealt with the emotional world. That’s the short answer.

The long answer is that right after it happened I did a lot of writing just to come to some understanding of what happened and trying to figure out what to do next. I did that for about five weeks, all the while thinking it might be best served as a comic because that’s what I’ve always done. Then, after about five weeks I stopped writing and turned my attention to forming, structuring, and drawing the comic.

Dueben: It was that soon that your response was, “I need to process this through art.”

Hart: Yeah, because again, that’s the main thing I do. That’s when I wasn’t drinking or crying or walking. Just trying to record and find answers, basically.

Dueben: To prepare for this, I was reading some of your older work like Hutch Owen. I kept thinking how so much of that is an emotional reaction to what was going on. It was fiction, obviously, but in that context, Rosalie Lightning felt like a similar response to the world.

Hart: I think that’s true.

Dueben: Rosalie Lightning is of course unlike those other books, autobiographical.

Hart: It’s not the first time I’ve made a memoir, but it’s the first time I’ve drawn one. I wrote a very quick travelogue in 1993 or 1994. I think it came out before Hutch Owen. That was also a very quick processing and response to an intense experience. That experience was nothing serious–it was adventure and reflection and some sexual tension. It came along in a similar way. When the experience was over I just sat down and tried to retell it. In the case of Hutch Owen, at least the first book, the process was extremely similar. I did tons and tons of writing for that book, an entire binder full of writing. The binder I had for the Rosalie book looks very similar and the situation is similar too in that I took all the writing and then shaped it into the form and drew it in both cases. It was very surprising. It’s the only two times I’ve worked in that way.

Dueben: With Rosalie Lightning, did you have a model for the structure or approach, or were you just doing it by feeling?

Hart: I was mostly going on intuition. To my mind it looks like it’s chronological and straight forward and then I look at it and realize it’s not. [laughs] I really wanted to honor the thoughts– I wanted to honor any train of thought and just follow it so yeah, it was all intuition.

Dueben: It’s not a linear book, but I know what you mean.

Hart: The basic momentum of the story is that here are the places we went to and the conversations we had. In another odd echo, that is how I thought of the first Hutch Owen story, which was just a bunch of places where conversations happened. It isn’t much more complicated than that.

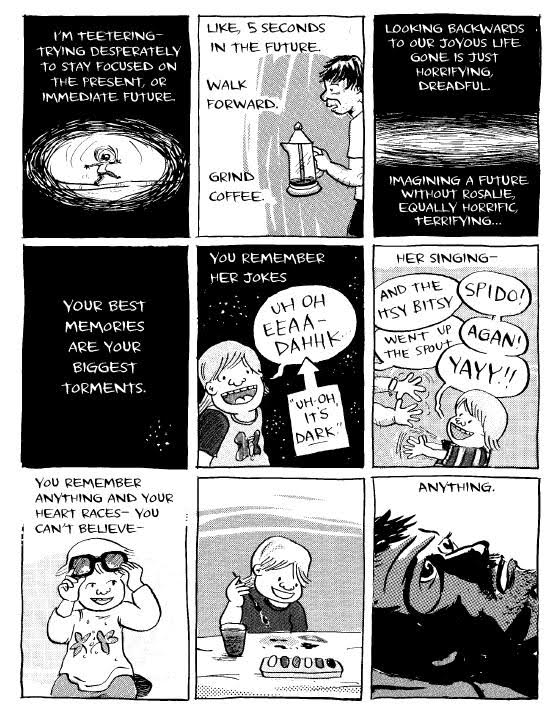

Dueben: One thing that struck me, especially on re-reading the book, is what you don’t depict. We know she dies, but you’re not trying to make us cry, we’re not there with you in the hospital for hours. How much not to show seemed to be key.

Hart: It was a decision I made, but it was an accidental decision. Early when I thought I had to tell this story, I was going to tell as much of the horrible stuff as I could. That seemed like it was important. Maybe it was a perverse desire to make other people suffer, too. I don’t know. But at a certain point I realized that I had some scenes outlined that I didn’t want to draw. I didn’t want to draw them and I didn’t think anybody would want to read them. It made me think, this is the wrong stuff to include in the book. I’m not trying to tell the story exactly and I’m not trying to tell the worst of it. I needed to take a step back and figure out why I’m doing the book. I realized that it wasn’t about just depicting a bunch of horrible events. I think at that point I started acting a little more judicious in how I edited and what I took out.

Dueben: I do not have kids, though I’ve had friends and family who have died, and as painful as it must have been to depict her talking and playing and drawing, that was preferable to dwelling on those last hours.

Hart: Yeah, that’s right.

Dueben: I suppose that’s an artistic choice, but it’s also how we grieve and move on.

Hart: Right. It was both of those things. It was artistic choice probably second and just what I wanted to focus on mentally. What I wanted to let my mind experience. I didn’t want to focus on the suffering. I wanted to remember what was good, so yeah, they both coincided. The book really reflects what was in my mind at the time. The mind and the book are the same in a lot of ways.

Dueben: You open the book with a quotation by Ben Lerner, which reads in part “there is no such thing as non sequitur when you’re in love.”

Hart: It’s a quote I heard when he came and spoke in my town. I was really moved by that line and I realized that that is exactly what is going on in my book. That in trying to recapture this loving time, trying to find some sort of other representation of my daughter and the love of my daughter, I saw it everywhere. There was nowhere it wasn’t. It just seemed like that exact same experience. It seemed like I was trying to explore again this feeling of being in love and what I mean is that everywhere I looked I saw my daughter and reflections of our story. It just felt very relevant. And also it sets the tone for the book right away which I thought was useful, too.

It was mostly about seeing her reflection. I guess maybe love and grief are very similar because you’re very open to experience. At least they are for me.

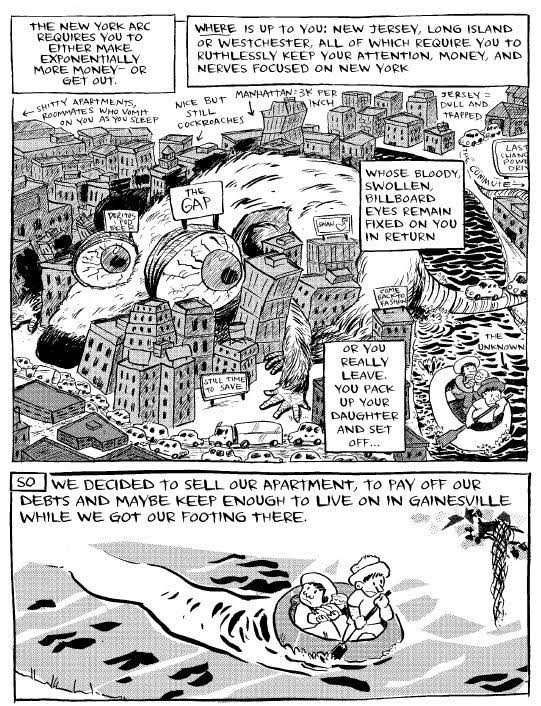

Dueben: A lot of people know that you left New York a few years ago and started SAW and you depict some of this in the book. Could you talk a little about Florida and what you’ve been doing?

Hart: Well, I’m trying to create the school I never went to but I would have liked to have gone to. It’s very intensive. All the teachers take it very seriously. We work really closely with all the students. It’s affordable because it’s not tied to a larger institutional structure. Nobody’s making a lot of money off of it. It’s just a place where students and artists can be in the same room and learn under guidance. We have the library in the same room so we have all this history behind us and with us for inspiration. I’m just trying create a high impact but low cost school.

When I was a teenager I really wanted to go to a comics school. I really wanted to learn comics and I went to SVA for one year. At the time, 1987, [SVA was] the only school you could go to for that. I was extremely disappointed. It was so expensive that my mom had to take a second job. All the students around me were complete lunkheads and utterly incapable of thinking about art. And the whole structure of it didn’t seem to see me as a person. Maybe that’s my fault for being seventeen and being not really big on stressing who I was as a person, but all the other factors were pretty important. I dropped out and I moved to Seattle where I met five or six other cartoonists my age and we had this support group for each other and we taught each other how to make comics. Ideally I would have gone to the school I’m running now. Four or five great teachers, ten or fifteen students, a place to read and classes to learn in, and all that stuff. That would have been my ideal situation.

Dueben: You mentioned that you were part of this nineties group of Seattle cartoonists along with Jason Lutes and Megan Kelso.Another member of the group was James Sturm– you’re both about the same age and you both started schools.

Hart: Yeah, go figure. [laughs] It’s possible that our generation was the first to take [comics] seriously as something which could be studied and not just a reaction. The undergrounds, which are our forebears, were reacting to the culture and they were reacting to comics history and lots of things. The post-undergrounds, that would be Dan Clowes and Chester Brown, I think they were starting to turn the form into something less reactionary, a little more thoughtful, and I think that their generation gave us a cushion to treat it as something serious. We were the first generation to think it should be studied seriously. Also by that point in an art form’s history there’s enough knowledge in the generations past that you can learn from generations past, which isn’t always true in a new art form. Jazz is the same way. Maybe that’s why James and I formed schools.

Dueben: And each of you felt the need to start your own schools.

Hart: James creates things too. I think I’m more scrappy by necessity but James is an inventor. He likes to be the head of things. He trusts his own vision enough to want to be in charge. As do I. [laughs]

Dueben: And as you say your generation is full of artists, people like Matt Madden and Jessica Abel for example, who have been teaching and working.

Hart: Yeah and it should be noted that when we were drawing comics we were thinking as we were drawing; we were considering the larger context. Not that other generations didn’t think about it, but I think the form was as important as the content in our case because there was such a breadth of history to reflect upon. We were always trying to locate our own work inside that history and so it made us really ready to teach when it was time to give back at a certain age.

Dueben: I mentioned earlier that it has been a few years since you came out with a new book. Did the move interrupt things? I’m just curious how you work and how you’ve been working.

Hart: Well from 2005-2008 I was doing daily strips seen in New York and Boston commuter papers called Metro. The plan was to collect them and they’re available online, but we never printed the collection on paper. In 2009 things got more complicated and that’s one reason we moved away. We were struggling so hard to find the time to create and New York send syou in so many different directions if you’re a freelance artist, running from one gig to another trying to land something. In 2009 I was preparing a daily strip with a friend of mine, Margo Dabaie, for King Features, that never really got seen. It took up at least nine months of our time. That wound up creating maybe five months of strips which are out there somewhere and if I get around to it, I’ll collect it. Then Rosalie was born in the fall of 2009 and that’s really when things slowed down, which I think is understandable. I wrote a book about her earliest couple of weeks. I never drew it, I was going to get around to it. The truth is when we moved to Florida in the fall of 2011 I was prepping to do something new but I didn’t know what it was yet. I wanted to get my bearings first. And then we lost Rosalie two months later.

Dueben: You moved for many reasons but partly to have the time and space to work.

Hart: New York just pulls you in so many physical ways and mental ways and financial ways and emotional ways. It’s always putting pressure on you– at least it was for us. I think most people have that experience. At some point we realized enough was enough and wanted to move to a place which was more conducive to making art and a simpler existence where that art making could be folded into.

Dueben: And Gainesville, at least in your book, is a nice, very bike-able place.

Hart: And lots and lots of creative people. It’s extremely vibrant creative town. There’s a good art department at the University of Florida. It has a lot of people inside of it who are interesting. The scientists are super interesting. There are people not connected with the university doing interesting work. It’s a great vibrant community and a great vibrant university town. I like it a lot.

I’ve managed to create this funky school out of these funky buildings with little resources and I never would have been able to do this in New York. I couldn’t have even thought about it there. It’s not been easy, but more often than not the answers to most of my requests have been, yes. Can I get this building for this price? Can I smash down this wall? [laughs] Can I build a ladder here? Can somebody help me move these books? In all these cases, I’ve been able to find help. It’s an easy and emotionally giving environment.

Dueben: When people hear what Rosalie Lightning is about, I think they might expect a book that’s painful to read, but it isn’t. What’s it like now that the book and the experience are at a distance?

Hart: In some ways it feels like the final stroke in a ritual designed to help me move past the experience. Rituals are designed to incorporate our solo selves into the larger series of existences of humanity. Especially in a society. So we get married in a certain way or we mourn people in a certain way. Any number of rituals that are designed to remind the individual that they’re part of a larger stream of human. I’m not a person that is very good with other’s rituals. I tend to have to make my own it seems, but nonetheless, the need to go through some sort of experience in order to note that you have been through it is important.

I didn’t realize this but it does feel like now that that the book is done and I have to talk about and in some cases show some pages from it and sign copies, it does feel like the final part of a ritual. Maybe the capping of the candles or something. I’ll never put the experience behind me, but I need to become the person who has had that experience. The effort of making the book, which was three and a half years or something, was the main part of that. Seeing it in print and reflecting on it, I can’t quite articulate it, but it does feel that this is the final part of a ritual. The final part of the ritual, but not the experience.

Rosalie Lightning is available now.