by Alex Dueben

Alex Dueben: Where did the idea for this book come from? What made you interested in making a graphic novel?

Meg-John Barker: Icon books have this whole series of books called ‘Introducing…’ where they try to make complex academic or political ideas accessible and engaging to everybody using the comic format. When they asked me if I’d be interested in writing one of these books about queer I was so excited. My love of comics goes back to childhood and I’ve been heavily into graphic novels all of my adult life. I also found the Introducing books super helpful myself when I was a student and trying to wrap my head around existentialism, Freud, or Foucault, for example.

At the same time as having a passion for comics, I’ve always been convinced that queer theory and queer activism has a lot to offer everyone, not just academics, activists, or people who identify as queer. So this was my opportunity to get that across.

Dueben: What was the process like? What did you give Julia and how were you initially envisioning the book?

Barker: The process was huge fun. First I made a big spreadsheet of 176 rows to match the number of pages I needed to write. For each page I came up with a title, some text, and some writing about the kind of images that I thought would work well. Once I was done, my editor Kiera Jamison looked over the whole thing and made lots of helpful suggestions, and I did a couple of edits based on those. Then Julia Scheele – the illustrator – sat down with me and Kiera and we went over every page together chatting about all of our ideas and making decisions about what it would look like. Julia then spent a few months going through it page by page and drawing her illustrations. She’d send those to me and Kiera in batches and we’d offer any feedback we had. The experiences of seeing the final illustrated pages was absolutely brilliant – so exciting every time I got some more in my inbox.

Dueben: Did you have a model as you were working on the book?

Barker: I guess the other Icon Introducing books were our model, but also we wanted to do something a bit different which would have the right look and feel for the topic of queer. In terms of content I was influenced by some of the great queer and trans activist authors like Kate Bornstein, Riki Wilchins, and Julia Serano who write very accessibly about queer ideas. In terms of style I think that Julia, like me, is influenced by brilliant queer comic creators like Alison Bechdel and Erika Moen.

Dueben: Okay so I just want to establish terms because I know that people can be caught up and struggle with terminology. So people have a sex–male or female. That’s biology. So what is gender? People might sometimes use them interchangeably, but I know that they don’t mean the same thing.

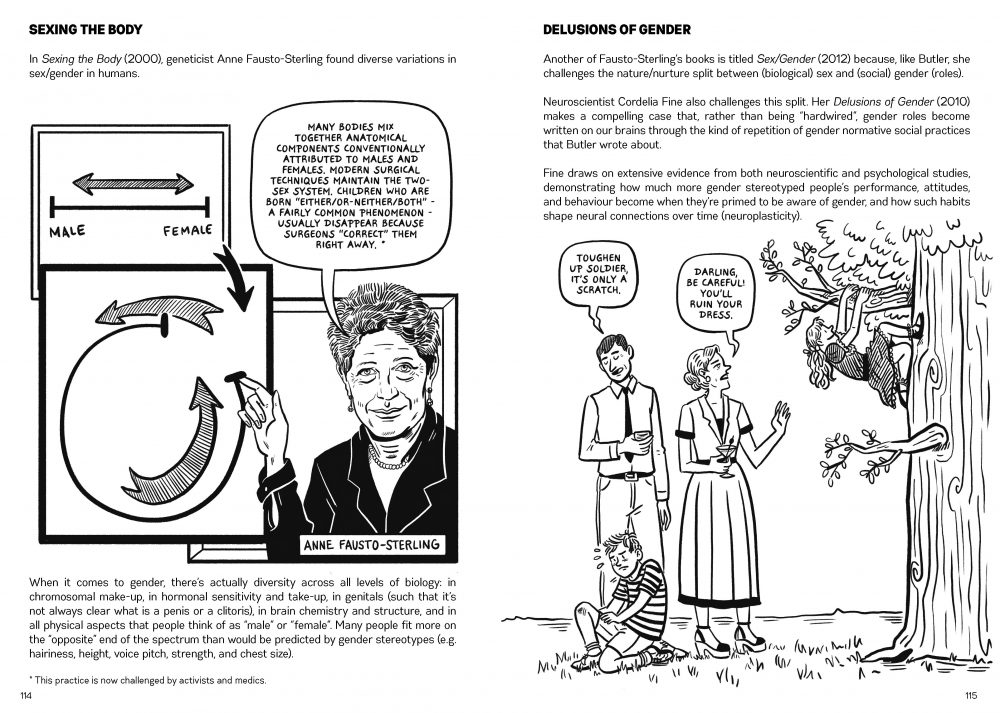

Barker: I wish the answer to this was simple but it really isn’t! People often think ‘sex = male/female biology’ and ‘gender = the social ideas about what it is to be masculine and feminine’. But it’s not that straightforward. For a start biological sex refers to lots of different things: our chromosomes, our levels of hormones like estrogen and testosterone, the appearance of our genitals at birth, the way our brains our structured, the way the rest of our body looks, etc. None of those things is strictly binary (just male and female), there is diversity on all of these aspects. Secondly, the way that we’re treated in life – due to cultural ideas about gender – also impacts back on our body. For example, things that we do can impact the way our brains wire up, how our bodies appear and move, and the levels of circulating hormones that we have. A lot of queer scholars therefore talk about sex/gender rather than sex and gender – given that it’s not really possible to tease the two apart.

Dueben: I think people often get confused because when talking about the “gender binary” people go, so male and female?

Barker: As you can see actually it is pretty complex, so perhaps it makes sense that we’re quite confused! The simplest answer is to not think that any aspect of sex/gender is binary. It’s all diverse. And all the different elements of sex/gender add up to make each of us a pretty unique individual sex/gender-wise.

Dueben: So if I understand you right, a woman who wears her hair in a certain way, does her nails, dresses in a certain way, she is acting “feminine,” which is a behavior. It’s a series of actions, and she’s responding to a cultural idea of how we define “feminine.” Meanwhile a crossdresser is a man who is acting in a way that responds to that same “feminine” ideal. The man is not responding to the woman, but both are responding to this “idea.” Do I have that right?

Barker: I know the bit of the book you’re referring to here where we have the great pic of a cisgender woman asking a drag queen why they dress like a woman, and the drag queer responds ‘why do you dress like a woman?’ The point is that both of them are reproducing this cultural idea of femininity and therefore neither of them is being any more or less authentic (and the same could be said for a cis man and a drag king in relation to masculinity).

This relates to Judith Butler’s idea of gender performativity: that gender consists of a set of practices that we repeat over and over again as we dress, talk, and move around the world. Because of the repetition it comes to feel very ‘natural’ but there’s no real natural gender. We can see that when we look over time and across cultures and see that people perform gender in very different ways. For example there have been times and places where long hair and skirts were seen as masculine, and the gendering of the colours of blue and pink used to be the other way around in the early 20th century.

Dueben: So I know people who use “queer” in a way that means non-normative and as an activist, and as a therapist, what do you think of that? Is it accurate? Acceptable? Wrong-headed?

Barker: As we explore in the book, ‘queer’ means different things to different people, and queer theorists and activists have embraced the fact that the word itself is kind of shifting and contradictory (just like our own genders, sexualities and identities often are!) Some people still see queer as an insult, some use it as an umbrella term for LGBT people, and some regard it as a word for anybody outside of the ‘norm’, for example.

So using queer to mean ‘non-normative’ is totally fine, but what wouldn’t be okay would be to insist that that is its only possible meaning, or that everybody should use it in that way. A lot of queer theorists would also say that you can’t really identify as ‘queer’ (like saying ‘I’m queer’) because the concept of queer challenges the idea of any kind of stable self-identity. But, of course, queer does feel like a comfortable self-definition for a lot of people, especially those who see themselves as outside of both the heterosexual norm and the gay norm.

Dueben: This is a site that’s about an artform that’s about exaggeration, and comics can definitely qualify as “camp” if any artform can. You cite it in the book but it feels as though every year that passes, what qualifies as camp and its relationship to gayness has faded.

Barker: Yes that definitely seems to be the case. Camp has been appropriated by all kinds of groups over the years, most recently perhaps hipsters. So at the same time you see a lot of straight people taking on campness, and a lot of gay men trying to get away from the idea that they might be camp in an attempt to be seen more as part of the (hetero) norm. I guess, like queer, that means that what is regarded as camp changes over time.

Dueben: I did want to talk about bisexuality. I am old, or at least over 30, and I know that “kids today” often use the term “pansexual.” Are they the same thing?

Barker: Yep that’s definitely a thing! Partly it relates to a misconception about the term ‘bisexual’ that the ‘bi’ part has to mean ‘men and women’. Some people embrace ‘pansexual’ as a term because they worry that the word ‘bisexual’ implies that there are only two genders, which can be seen as transphobic given that many people – like me – experience themselves as between or beyond the gender binary. However, bisexual people themselves generally don’t define ‘bisexual’ in this way. Usually they talk about having ‘attraction regardless of gender’ or ‘attraction to more than one gender’, and they understand the ‘bi’ part to mean ‘the same gender as me and different genders to me’. So really there is a lot of overlap between bisexuality and pansexuality, with both terms referring to folks who aren’t limited to one gender in terms of their sexual attraction.

From recent research it seems that over 40% of young people see themselves as something other than exclusively heterosexual or exclusively homosexual. Some use the terms bisexual or pansexual for this, others use queer, others prefer not to label themselves, or use straight or gay even though their gender of attraction isn’t exclusive.

Dueben: I was fascinated and disturbed to read that both queer theorists and psychoanalysts tend to erase bisexuality and I wonder if you could talk a little about how this has happened.

Barker: Yes it’s something that distresses me greatly as a bi activist (I also co-authored The Bisexuality Report – https://bisexualresearch.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/the-bisexualityreport.pdf). Basically this cultural idea that sexuality is binary – that people are either gay or they are straight – seems to be so strong that even queer theorists themselves fall into the trap of erasing bisexuality. I’ve heard prominent queer theorists give talks where they speak about gay, lesbian, straight and trans people, but never mention bi people – and when confronted about this, suggest that bi people should just get over labeling their sexuality! As if that idea of not-labeling applies so much more to bi people than it does to those other groups.

Psychoanalysis generally sees bisexuality as something that we have in our pasts: a phase that we grow out of. Queer theory, on the other hand, often relegates bisexuality to some utopian future when we’d all be beyond labels. Neither of them actually engage with bisexuality in the present, which is a shame because there’s some awesome bi activists and scholars out there writing important queer stuff (e.g. Shiri Eisner, Steven Angelides, Maria Pallotta-Chiarolli).

Dueben: One reason I’m disturbed is because I know how average people react to bisexuality–many individuals often don’t believe it exists or treat it like a joke–and leaving aside my own feelings, it seems anti-queer to approach it like that.

Barker: I know right?! It seems so weird to me that queer theory and activism have so often embraced and celebrated trans, and have so rarely engaged with bisexual people or experiences. In fact, both of these groups challenge normative sexuality and gender binaries and identities in important ways, and both groups also fall back into those binaries and identities sometimes.

Dueben: I bring up bisexuality because it’s interesting that for the most part people seem to have accepted this idea that sexuality is a spectrum–even if they simultaneously won’t date a bisexual. But the fluidity of being bi is something that feels like a very accurate reflection of queer theory. Do you see this changing? Do you see ways forward to push for this?

Barker: Yes it is really interesting that people can accept that sexuality might be diverse and fluid, at the same time as still having discriminatory views and behaviours about bisexual people. I guess those old assumptions remain powerful. For me I do think the way forward is to keep emphasising gender and sexual diversity: moving people away from old binary models and helping them to see that all of us have diverse genders and sexualities – no two identical. I’d love to see sex and relationship education in schools that taught these ideas of diversity, as well as more diverse representations in the media instead of tired old stereotypes of bi people as evil, tragic or confused.

Dueben: One idea you come back to throughout the book is “Queer=Doing, not being.” Can you talk a little about what that means to you both in terms of thinking about these issues and just living one’s life and daily life.

Barker: For me it’s a helpful warning not to fall back into another dangerous binary or queer/not queer. If we think of queer as something people are then we can easily start judging people according to some hierarchy of who is queer enough (and who isn’t). This is just a reversal of the normative hierarchy that judges people for being too queer. All kinds of people share the experience of sometimes being judged as not queer enough in their identities, appearances, or politics, for a specific event, venue, or community (e.g. femmes, queer people of colour, disabled queers, older queers, bisexual folks, working class queers, fat queers, asexual people).

When we think of queer as something that we do, rather than something that we are, then we can move away from that kind of binary them-and-us thinking, and consider queer as something we could all endeavour to practise in our lives, whatever our gender or sexuality. For example, we can do queer through thinking critically about the media representations of gender and sexuality that we see, through expressing ourselves in ways that ‘queer’ binary understandings of sexuality and gender, and through insisting that normative sexual practices and identities are subject to just as much scrutiny as non-normative ones.

handmadelure members ryderchandler7 luvxp groups juventus altacasen sdcollege groups madrid elanehunl bebindaas groups juventus antoniadu quest4questions

question 199&qa_1 fotbollstr%C3%B6jor marlenema travel adrenalfatiguerecovery

groups billige fodboldtrojer tressakqh

Comments are closed.