By Avery and Ollie Kaplan

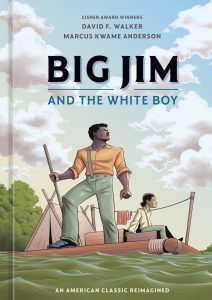

You’re almost certainly familiar with Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn in some form or another. But you’ve never heard the story as it is portrayed in Big Jim and the White Boy. The graphic novel retelling of the story is written by David F. Walker, illustrated and with lettering by Marcus Kwame Anderson and colors by Isabell Struble.

Big Jim and the White Boy is available now at your local bookstore and/or public library from Ten Speed Graphic. And it was nominated for the 2025 Eisner Award for “Best Publication for Teens.” At San Diego Comic-Con 2025, Comics Beat caught up with Walker to ask all about the graphic novel.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

THE KAPLANS: Can you introduce yourself to our readers?

DAVID F. WALKER: I’m David F. Walker, and I write comics and graphic novels. And I’ve been at this longer than probably some of the readers have been alive. I’ve worked for a lot of different companies: Marvel, DC, Image, Boom, Dynamite, Dark Horse. You name it.

Co-creator of Bitter Root, writer of Big Jim and the White Boy. And a bunch of other stuff that hopefully people have heard of, but if they haven’t, now’s their time to discover their new favorite writer.

KAPLANS: Where do you suggest people start with your body of work?

WALKER: I’m more than happy with Big Jim and the White Boy being an introduction to my work, in part because it’s in print. A lot of my past work, especially for Marvel, is out of print. I’m not ashamed of that work, but it’s not easy to find. But I think Big Jim and the White Boy is not only the best thing I’ve done at this point in my career, I’m concerned it might be the best thing I ever do in my career.

Marcus, the artist on Big Jim and the White Boy, and I would joke about this: if I had planned things better, this would have been my retirement book. But no, I’m bad with planning things ahead, so.

KAPLANS: If anyone wants to read your Marvel books, they can always come visit our house.

WALKER: Or, I was just talking to Sanford Greene about this: next year is the tenth anniversary of the beginning of our run on Power Man and Iron Fist. How about they do a tenth anniversary collection? Because there’s three volumes of it, and all three are out of print.

That’s one of those frustrating things, that especially young aspiring creators don’t think about. They dream of working at Marvel or DC. I was certainly one of them. And then if you’re fortunate enough, you get that experience. And maybe you do work that you’re proud of, that you’re happy with. And then it disappears, and you’re like: am I going to have to wait until I’m dead? Because I don’t know what waiting after you’re dead is like. I’ve never talked to anyone who’s done it.

It’s interesting, because you spend so much of your life trying to get to a point where your work is in print and can be seen. And then suddenly the door closes on it because it’s out of print. And that’s just frustrating.

KAPLANS: Is something like Big Jim and the White Boy easier to get into a library, in case it does go out of print?

WALKER: Yes, and Marcus and I were just talking about this the past couple of days. I think this is one of those books where, if I’m lucky… Well, first off, if I’m lucky, I still have several years, maybe as many as twenty years left in my life. But that this is one of those books that will hopefully outlive me. And I don’t say that lightly.

We’ve always lived in a time where a lot of pop culture is pretty disposable. And comics, despite how many poly bags you may have and how much acid-free cardboard you have to store them in, a lot of it is meant to be disposable. A lot of it gets lost. A lot of publishers have a limited shelf life for how long they’ll keep a book in print and available.

And I just hope that this is one of those books that stays around for a long time. In part because I’d like to see more creators pushing to have work that seeks to expand the boundaries of what this medium is capable of. And not just superhero stuff, but really thinking outside of the box, bringing stories to life that twenty of thirty years ago we never would have seen.

KAPLANS: Can you explain how Big Jim and the White Boy expands the medium?

WALKER: Big Jim and the White Boy is a retelling of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, told from Jim’s perspective. But it’s a very drastic and dramatic retelling in that the vast majority of what is in Twain’s novel is not in this book. The two characters are there, Huck and Jim, but the story is drastically different.

When Marcus and I sat down and started working on the book, we talked about how Twain’s original novel is indeed a work of literature — whether you like it or not. Marcus and I agreed that we should be striving to achieve literature. And I don’t know how often other comics creators think that way. But we’re not just making a graphic novel; we’re not just making a comic that’s ten times longer than the average floppy. We’re making literature; we’re making art.

And that sounds really pretentious and I try not to be a pretentious person, but that was the goal. Personally, I wanted to make something that I knew would be on library shelves, but that I knew would be checked out a lot, that wouldn’t just be sitting there collecting dust. That teachers would use in a classroom, or that a “reluctant reader” would pick up it up and read the whole book all the way through.

I didn’t say this to him; I ran into Kyle Baker, who is in the top five influences of my life creatively. I’ve met him numerous times, we know each other. But when Baker’s book Why I Hate Saturn came out back in the nineties, it changed me forever. I stopped reading comics for nearly ten years afterwards. And I thought at the time, “I’m never going to read a better comic than this.”

And to be 100% honest, I think I’ve read maybe four that were on par with Why I Hate Saturn, which is now over thirty years old. And that book has stuck with me for so long. I wanted to make something like this. There’s no superheroes in Why I Hate Saturn, there’s no explosions.

That was at a time where every newspaper or magazine article would be like, “Zap! Pow! Comics aren’t for kids anymore!” And they would talk about Watchmen, The Dark Knight and Maus. Most people were leaving out Love and Rockets, because most people writing this articles were pretty illiterate when it came to comics. And they weren’t talking about Mage, and there were a whole lot of stuff they weren’t talking about that I’m coming of age reading, and saying, “Wow, you can do this on paper with just some pictures and words?” And that’s what really influenced me.

KAPLANS: How does it change your creative approach when you’re trying to make literature?

WALKER: I don’t think it changed the approach that much. The average comic is 20, 24 pages. Big Jim and the White Boy is 260. There are things Marcus and I talked about: in a standard floppy comic, if a scene runs longer than four pages, it’s too long. Four pages is taking up a fifth of your entire issue?

That’s in American comics. You look at manga, and manga is very decompressed. I’ve seen scenes that run ten, fifteen pages. So we talked about that: we can decrompress a scene here. A scene that we might be forced to do in two pages, now we can do in six or seven.

So let’s play with the concept of the unreliable narrator, and let’s jump back and forward in time. There were these moments where I’d ask, “How do I do this scene in a way that I’ve never seen it, or that would be exciting or different for people?”

If you’re doing a comedy, you don’t want people saying, “This is funny.” You want people laughing out loud. If you’re trying to do something that’s sad, you want them crying. Those are the things that we should be trying for as creatives. And that’s what Marcus and I were striving for above everything else.

But it’s the readers who make the decision that it’s literature. It’s the readers who either accept the book or reject the book. So for Marcus and I, we just made the best book we were capable of making, and then we let it be what it’s going to be. The final collaborator is the reader. So every person who reads the book becomes part of our team. Ultimately, the question isn’t “how did we get this to be literature?” the question is, “do you see it as literature?”

KAPLANS: Why did you want to retell Huckleberry Finn in particular?

WALKER: It’s kind of funny, because I had started writing this book as prose ten or fifteen years ago. It was simply because when I first read Huckleberry Finn when I was twelve years old, I always had the same question: why the hell is Jim hanging out with this guy? He’s running away from slavery, but he’s hanging out with this skinny white kid.

And he’s going down river; he’s going further south. If you’re a runaway slave, there’s three directions to go: there’s north, east or west. You never go south. North is primarily where you want to go. Or there’s a couple states, like if you’re in Missouri, you could go east or west as well. So I always asked, “Why?”

Then at some point, I thought it would be funny to tell Huck Finn from Jim’s perspective. And at that point, it was more of a Blaxploitation story, from the seventies. It was way more over the top and violent. And then it just started collecting dust; I never got too far into it.

Later, Marcus and I were working on The Black Panther Party for Ten Speed. And Ten Speed came to me and said, “We’re thinking of doing reimaginings of certain works of literature. Would you be interested in that in general, but in particular we were wondering if you’d be interested in Huck Finn.” And I said, “As a matter of fact, I happen to have something right here… Tah dah!”

It really happened pretty quickly. We were still working on Black Panther Party; I may have been done writing it, but Marcus wasn’t done drawing it. The conversation started pretty quickly, and then it became clear to me that the book that I’d been envisioning for a long time but not working; I didn’t have much interest in writing that version. So I had to start thinking, “What’s the version I do want to write?”

And equally important, this book is going to have pictures in it. Pictures are just words translated into a different language. So what am I doing with that? Of course then you’ve gotta find someone who can translate those words into pictures. And Marcus is a genius about that.

KAPLANS: What’s your collaborative process with Marcus like?

WALKER: Marcus is the best creative relationship I’ve ever had. And part of it is because he and I have a lot of the same sensibilities in terms of film and music and literature and our love of history.

So I knew aspects of the story, I had most of it outlined, but then an idea would pop in my head. And I’d say to him, “Hey, I got this idea. What do you think about this?” And then I’d ask how in-depth he’d want me to go in describing the scene. Because some artists want you to choreograph the action panel by panel; others want you just to give them freedom. And Marcus falls in between the two. But both of our first priorities were the story.

I would send him the script pages, but I would give him what I would call the “green light.” I’d hand him forty pages at a time, and say “pages 1 through fifteen are locked in stone. Once you get to page fifteen, let me know.” So I was writing it like I was writing a monthly periodical. Because I knew I might fall behind schedule at some point, and that might mean we’d have to push back the publication date, but I never wanted my falling behind schedule to impact his schedule. And that happens a lot in the graphic novel world, because a lot of publishers want you to turn in that 250 page manuscript before the artist starts working on it.

But because we had success with The Black Panther Party, our editor knew us, our publisher knew us, there wasn’t much pushback. Although to be 100%, we might not have told anybody we were doing it that way. I seem to recall, when I turned in the 250 page final draft, I turned in the first 80 pages that Marcus had drawn, and they said, “What?” They were happy, and I think they ended up pushing the publication date back, but I’m happy with the results and it was worth the wait.

KAPLANS: You’re an educator, too. Why is telling this story as a graphic novel important when educating people about these topics? Why is the format so good for that?

WALKER: I think it’s good for it just because I think most people respond better to visuals than they do a big block of words. I mean, I’m an old man who still loves books with pictures. So I think that draws people in.

And I think that this medium, and depending on how a picture is drawn… Marcus, the argument could be made that his style is very cartoony. And that cartoony style disarms people and they think, “This is going to be a fun book.” Then they get to page 25 and they’re like, “Oh my god, what’s happening here?” I love that stuff.

And I loved the old EC Comics Tales From the Crypt, stuff like that. And of all the artists who worked for EC, my favorite is Jack Davis. And Davis would do those stories, and they were cartoony and terrifying and thrilling. That draws you in; or at least it drew me in as a kid. Sometimes because it starts out looking like this is an OK book to read, and then at some point you realize, “Maybe I shouldn’t be reading this. Maybe my mom will get upset, because this clearly isn’t PG-13.”

For me, there’s so much you can do. There’s very few limitations within this medium. Limitations are page count, things like that; you can’t have sound, you can’t have motion. But beyond that, the limitations are what you place upon yourself as a creative. So you should be able to layer a story; it should be able to have a subtext, it should be able to have educational components without hitting you over the head with an anvil.

To me, because of the subject matter; because this book is about a man who is enslaved and escaped slavery and is searching for his family. And it’s set in one of the most volatile regions of the United States at that time, in an area where the American Civil War started… It didn’t actually start when Southern states seceded, it started in the conflict between the Kansas Territory and Missouri. I wanted people to understand that. And I think Twain wrote a great book, but he left all of that out, and there’s no reason to not put that in. If I wanted to separate this book from that book, this is what I felt I needed to do.

KAPLANS: And graphic novels are uniquely suited to creating empathy in readers.

WALKER: Without getting into specifics because they’re full of spoilers, there’s some scenes in here that I don’t know if as a writer I could have written them so that they would have gotten the emotional response I really wanted. But I knew Marcus could draw those emotions.

And then you see those emotions, and without music to manipulate you, we’re calling upon your ability as a human being to summon empathy for a cartoon character. And if we’ve done that sucessfully, that says a lot about us, but it also says a lot about you as the reader. It says that you have enough of your humanity left intact — and let’s be honest, we’re living in a time where that’s trying to be denied us — if you can have some sort of empathy for a two-dimensional cartoon character that’s not moving, you’re actually doing better than you might realize.

So the biggest compliment we’ve gotten with this book has been whenever somebody says, “You made me cry.” My response is both “thank you” and “you’re welcome.” Because that means you’re still alive. You’re still feeling something.

KAPLANS: And the cartoony style specifically helps convey emotion.

WALKER: This goes back to what I was saying about the reader being the final collaborator. I used to spend some of my summers, I was a volunteer counselor at a camp for kids with muscular dystrophy. Most of the kids were in wheelchairs and they had mobility issues, some of them had cognitive issues.

I was writing a book for Marvel, and one of the characters in the book was Wheels Wolinski — a guy in a wheelchair. How original is that? You call a guy in a wheelchair “Wheels Wolinski.” But I wanted to use the character. And it was never said in his entire history why he was in the wheelchair.

So I got the assignment to write Occupy Avengers, Wheels was going to be in it. I reached out to some of the kids that I worked with, who by now were in their twenties, and I said, “I’m working on this project, one of the characters is in a wheelchair, and I’m asking you specifically, do you want to know the reason why he’s in the wheelchair?” Every single one of them said “No. The moment you tell us what it is, I’m not going to be able to relate to him as much.” I wasn’t expecting that answer.

But that’s really stuck with me over the years. If you give somebody just a little bit, it’s amazing how much we can see ourselves in just a tiny little thing. And when you’re not being represented or you’re feeling under-represented, we’ll take a little bit and run with it. I think about that a lot.

And I think about that with some of my students — I’ve had students on the spectrum, who are trans, just a wide swath of humanity. And they all ask, “Well how do I represent myself?” And I answer, “First off, you get at the heart and soul of your humanity. But you leave just enough detail out that somebody else reading it can say, ‘Oh, that’s me.’”

And if you don’t think it’s possible, look at Mr. Spock. Because Mr. Spock is the one character that everybody relates to, just about. And I remember talking to somebody about Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, because they were like, “Oh yeah, beacuse the Trills are all trans.” And they explained it to me, this was about ten to fifteen years ago, I was like, “Now I see it.”

But that also helped me inform me as a storyteller: give the reader enough that they can find something that they can go, “This is me.” And that also I think helps ignite the imagination of other people, and make them go, “Oh, I could do this. I should try this.”

Big Jim and the White Boy is available now at your local bookstore and/or public library.

Stay tuned to The Beat for more coverage from SDCC ’25.