These days, the vast majority of comics sold in the United States are sold through bookstores, but it wasn’t always like that. In fact, up until the early ’70s, you couldn’t find comics in book stores at all. They simply were not published in collected form with bound spines, not until a young publishing staffer, Linda Sunshine, had an idea.

Sunshine was early in her career, working for Crown Publishing, and she’d done a book of superhero posters that sold well. This gave her the idea to take comics — sold for decades exclusively in stapled single issues, mostly at newsstands, convenience stores, and head shops — and collect them, giving them hardcovers and putting them in bookstores.

This idea produced Superman: From the ’30s and ’70s, which did just that. It was a collection of reprinted material from throughout the history of the character, complete with an introduction and a bibliography. The book was a success, giving rise to a series of similar books — focusing on everything from Batman to the origins of the characters of Marvel Comics — and ultimately paving the way for the medium to become the fixture in bookstores that it is today.

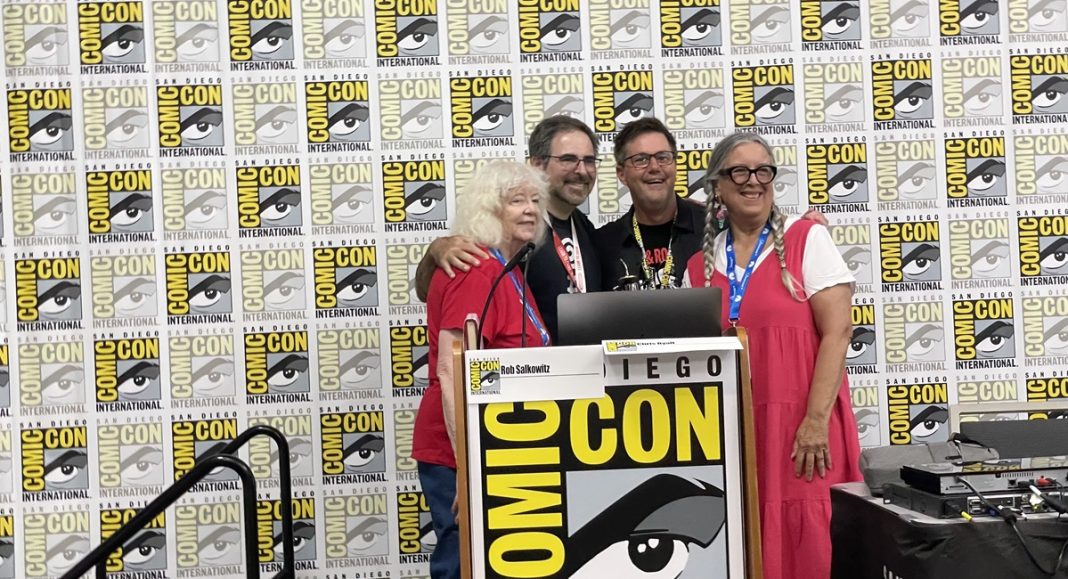

While Linda Sunshine’s contributions were massive, they were for many years largely unrecognized, but that changed at this year’s San Diego Comic Con, where Sunshine was a featured guest, appearing in a spotlight panel moderated by Rob Salkowitz — who helped identify Sunshine as a key figure — and Chris Ryall, of Syzygy Publishing, an imprint at Image Comics.

Salkowitz and Ryall, both influential comics figures in their own right, related stories of growing up at a time when comics were not found in bookstores, and, as a result, they were not taken seriously as reading material by parents. When Sunshine’s books started appearing in bookstores along side prose material, the pair said it fostered legitimacy.

To make the books happen, Sunshine recalled, she had to get permission from the person who controlled the rights to Superman, which in the early ’70s was legendary DC Comics editor, Carmine Infantino. Sunshine’s boss gave her $30 so she could take Infantino out to dinner and discuss the deal.

Infantino, Sunshine said, picked an Italian restaurant in New York City, sat down, and started ordering salad, steaks, and, finally, a bottle of wine. At that point, Sunshine protested, worried she wouldn’t be able to cover the bill — and Infantino burst out laughing.

“He thought it was the funniest thing he’d ever seen,” Sunshine said, “and that was when I knew he’d give me the rights.”

Over the course of the following years, Sunshine worked on a foundation of proto-comics collections, perhaps most notably The Origins of Marvel Comics by Stan Lee, which is going back into print with a pair of new editions this fall, edited by Ryall. Linda Sunshine worked with Stan Lee directly, who didn’t pick the exact comics that were collected there but did have final say. He also wrote an introduction.

Eventually, Sunshine’s long career progressed into other areas. She wrote non-fiction books and novels. She worked on the bestselling Jane Fonda’s Workout Book. She did a series of 30-some movie related art books, about pictures that ranged from E.T. to How to Train Your Dragon, from Stuart Little to Hulk, the one directed by Ang Lee.

Linda Sunshine’s career and spotlight panel were fascinating, filled with interesting publishing anecdotes. Ultimately, her story is an interesting study of how seemingly unorthodox ideas — or at least unproven ones — can ripple out into major cultural developments.

Ryall and Salkowitz shared their own personal stories about how Sunshine’s notion to collect comics changed their childhoods by getting the medium into bookstores, as I have my own, built around finding comics in libraries, on summer days when my parents set me loose and told me I could take home whatever I liked.

As Salkowitz noted at the start of the panel, “In the last couple of years, the market for comics in book form — graphic novels and trade books — has succeeded, surpassed, and doubled the money for comics sold in the direct market.”

Perhaps this was inevitable, but that makes it no less true that Linda Sunshine was the first to get comics on the path to bookstores and libraries, all the way back in 1973. One wonders, how many important comics people today wouldn’t have had access to the medium as children without her work?

“I think you should always do things you’ve never done before,” Sunshine said, “because they scare you, and that’s how you do your best work.”

FYI: I’m in the photo because I presented Linda with her Inkpot Award at the beginning of the panel.

I guess this holds true for the US, but by 1973, the French had already done it for decades, I believe.

The first comics (Bande dessinée in France) sold in bookstores was probably SAPEUR CAMEMBERT in the late 1800s then came the most famous BECASSINE in the early 1900s. Not to mention Rodolphe Töppfer’s books which were probably sold in Switzerland slightly before that.

Comments are closed.