On Friday, July 24th, at 10:00 AM Pacific Time, the prerecorded Howard Cruse: the Godfather of Queer Comics panel was released on YouTube.

Howard Cruse passed on November 28th, 2019. His legendary career included Gay Comix, Wendel, and Stuck Rubber Baby (currently available in a new edition from First Second). The panel was put together by Prism Comics.

The panel opened with an introduction from Justin Hall, cartoonist, editor, and professor.

“Howard Cruse was one of the greatest cartoonists of his generation,” said Hall. “And is affectionately known as among those of us in the LGBTQ comics community as the Godfather of Queer Comics.”

“Howard’s work was spectacular and groundbreaking, both in how he transformed the craft of cartooning and in the complicated content matter he addressed,” said Jennifer Camper (cartoonist, organizer Queers & Comics). “Howard was also an activist, a mentor, a community builder, and a very, very generous friend.”

The YouTube recorded included a whole swath of people who had been touched by Cruse and his work, and was divided into a series of “mini-panels” which featured different panelists and covered different periods of Cruse’s life.

Howard Cruse’s Early Days: Underground Comics

The first “mini-panel” was moderated by Karen Green (curator for comics and cartoons at Columbia University) and included panelists who had met Cruse early in his career.

“I met him in the mid-seventies, he came to San Francisco for one of our conventions and we got to meet him, and he was such a lovely guy,” said Trina Robbins (It Ain’t Me Babe, Wimmin’s Comix, Wonder Woman).

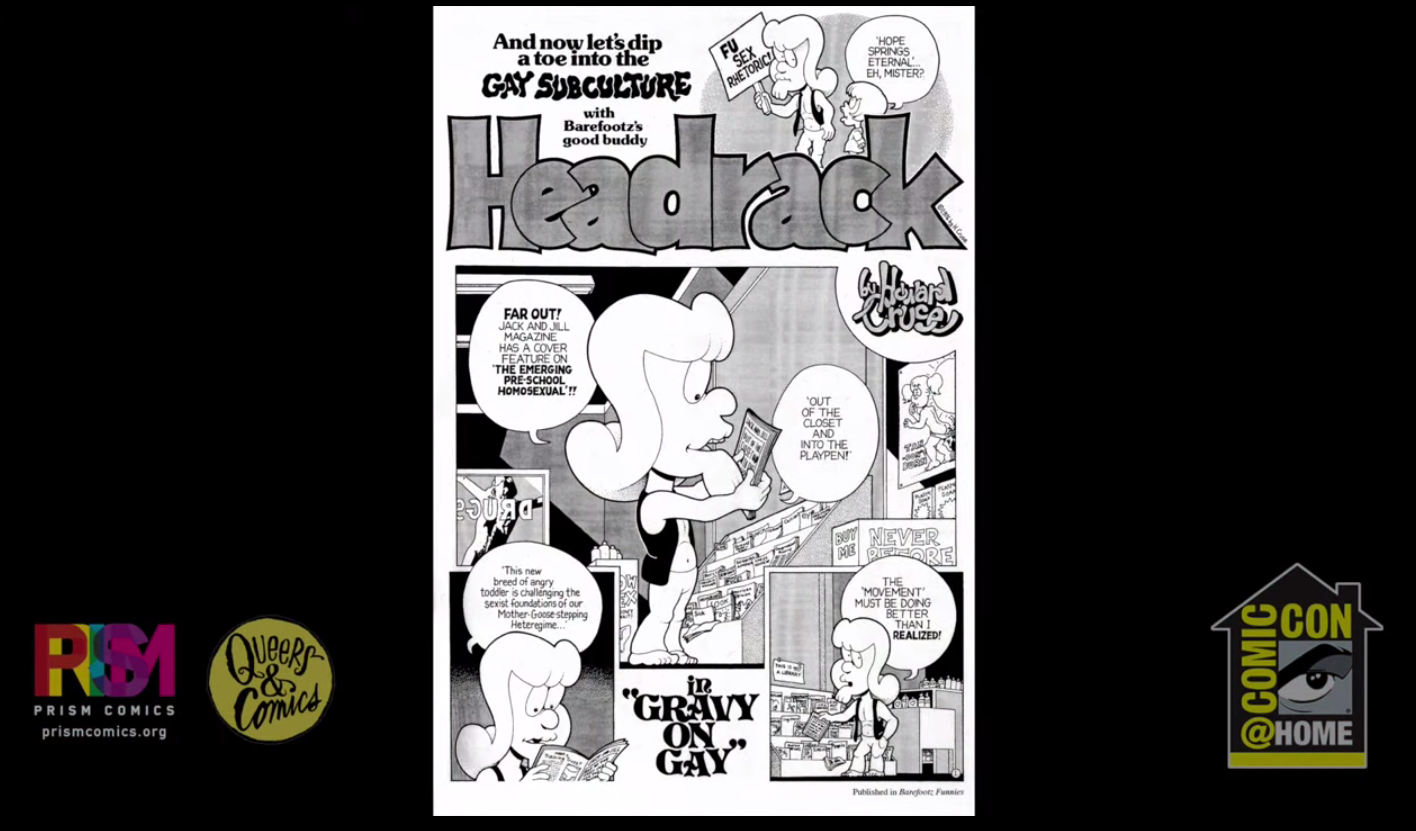

“When I was in college, there was a head shop where we bought all the comics – Barefootz and Crumb and all of Trina’s comics,” said Roberta Gregory (Naughty Bits, Bitchy Bitch). “To me it really stood out because it was in this cute style, but his sense of humor was really different, and that’s what I like.”

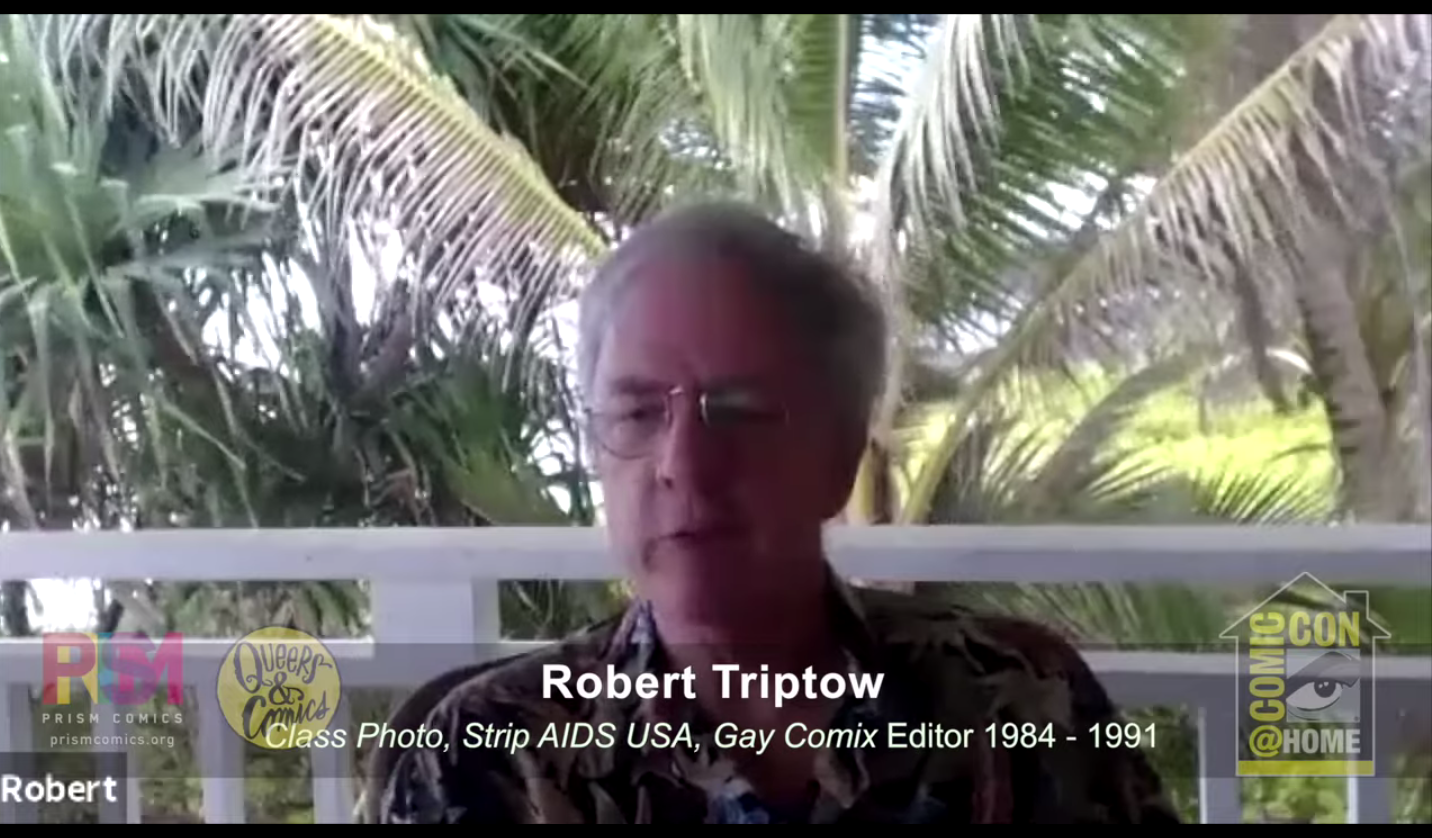

“I was a fan, I read everybody’s work, and I discovered Howard as soon as he was published,” said Robert Triptow (Class Photo, Strip AIDS USA, Gay Comix Editor 1984 – 1991). “His work is like a breath of fresh air compared to all the other male cartoonists.”

“What you just said about compared to the other male cartoonists,” said Robbins. “That was the thing, his stuff was nice, and in the underground, sometimes it seemed as though nice is a no-no.”

“I think we had a mutual friend in Lee Marrs,” said Denis Kitchen (publisher, Kitchen Sink Press). “They were involved in some kind of college syndicate. So one day I just got some of his samples in the mail, and he mentioned Lee. Of course, I would have loved his work even if it hadn’t come with a recommendation… But as everyone’s already noted, they were so different and so fresh. Superficially cute, but when you actually read them, they were often pretty heavy duty. They were misleadingly cute. So from the beginning, Howard found his way into I think every anthology I did – Snarf, Bizarre Sex, Death Rattle, you name it.”

Kitchen didn’t learn Howard was gay until they had already worked together for some time.

The revelations sowed the seeds of an important anthology.

“So, that was probably turning around in my head when I realized there ought to be an anthology of gay cartoonists,” said Kitchen. “So I remember asking him if he liked the idea and if he would edit it. And he said he loved the idea but he was frankly concerned that if he were to edit that, it could cost him his freelance career… so he thought about it for a while, and I know Eddie’s told me that he talked about it, and finally he said, ‘I want to do it, it’s important.’ And that’s when Gay Comix was born, in ’79.”

“I just felt how brave he was to do this,” said Robbins. “Not only that he might lose work in the straight, not underground world, but I have mentioned that the underground clique before, they were very homophobic – they were notoriously homophobic, those guys. And I just thought, ‘god, what a brave man.’”

However, putting together the Gay Comix anthology proved to be something of a challenge because so few gay cartoonists could actually live their lives authentically and openly.

“Howard had told me that he was inspired by Wimmin’s Comix and the work that people like Trina were doing,” said Gregory. “Getting people to tell real stories which determined the course he wanted to take in Gay Comix.”

“As a cartoonist, Howard was pretty unusual in his approach,” said Triptow. “I think the influence on that was that his father was a minister. Because Howard in a way was sort of a cartooning minister to us all. His cartoons were about how to live a happy life… They weren’t really sermons, but they were like parables.”

“You know, the importance of Gay Comix, that he opened up the previously completely cis-gendered underground comics scene, that’s a major accomplishment,” said Robbins.

Gays in Comics: Howard Cruse’s Legacy

Next, a short video played of Andy Mangles (Wonder Woman ’77 Meets The Bionic Woman, Gay Comix editor 1991 – 1998) sharing his memories of first seeing Gay Comix on the stands.

“I was 13 or 14 when I first saw Gay Comix on the stands, I could only afford a glance or two at it then, furtively,” said Mangles. “But it told me that not only were there gay comics, but there were also gay people creating comics. In 1988, I wrote the massive two-part article ‘Gays in Comics: The Creations and the Creators’ for Amazing Heroes Magazine. Not only was Howard the only person in the industry who I interviewed who would identify as gay, but he also provided an illustration for the article.”

Mangles explained that Cruse was always supportive as Mangles began his journey as the first openly gay man in mainstream comics, as opposed to underground comics scene.

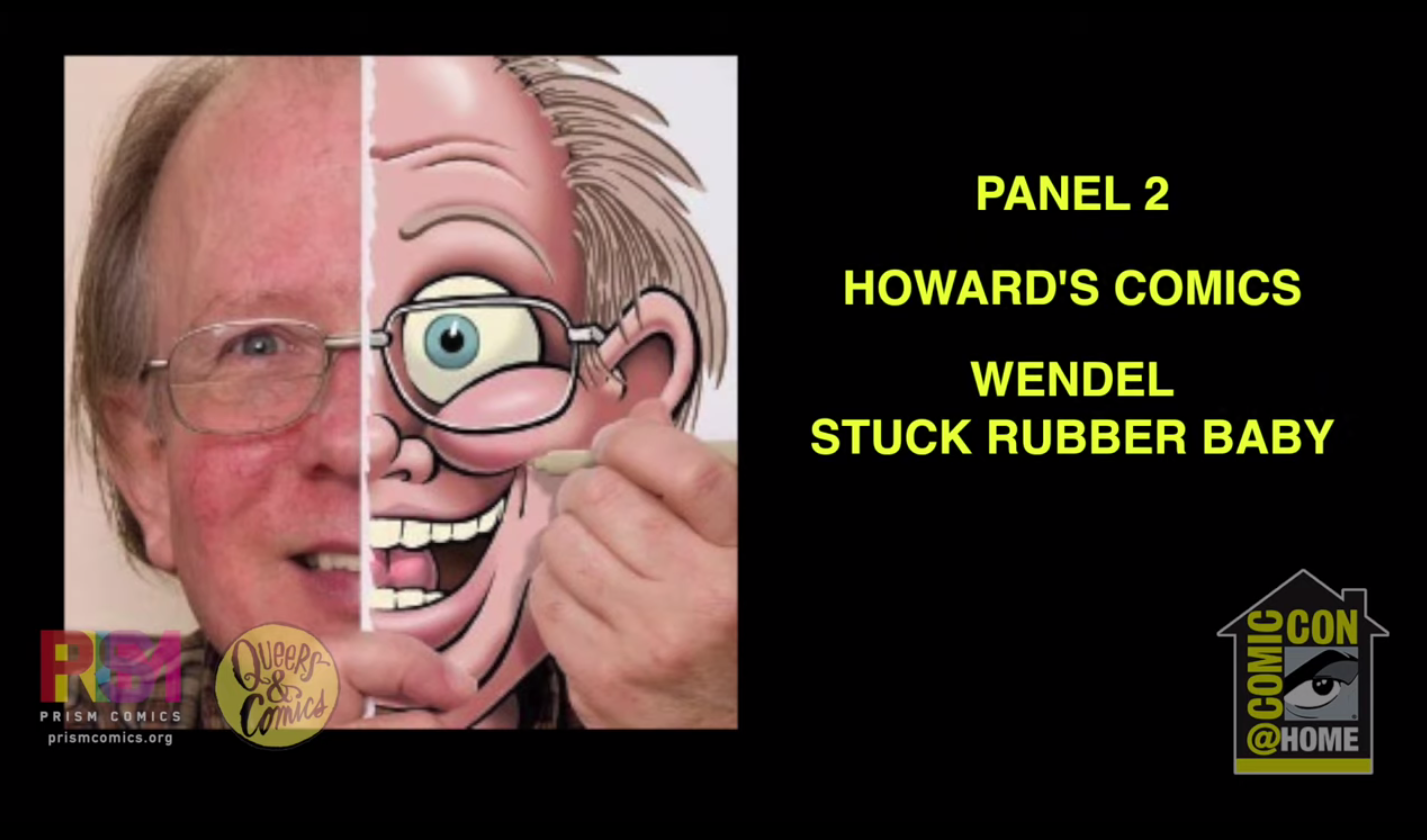

Panel 2 – Howard Cruse’s Comics – Wendel, Stuck Rubber Baby

The second panel was moderated by Camper and featured four cartoonists who had been influenced by Cruse’s work and kindness.

“Howard Cruse was such an important part of my life and queer comics,” said Camper. “And it’s really hard to imagine queer comics without Howard. He was one of my first mentors, and he created a community where we could all thrive.”

“Howard was a pretty big influence on me,” said Ivan Velez Jr. (cartoonist, educator, Tales of the Closet, Ghost Rider). “He took me to my first comic book conventions to sell my comics. He invited me to sit next to him, which was an amazing, interesting experience. Particularly since we had this bubble – it was such a crowded convention back then, we had this bubble that no one would go through and into it. It was like this weird void… we noticed that only the bravest people would go into it and pick up one of our comics. Not only was he a really big influence, he was just the coolest friend to have… he was like Mr. History of Comics, Mr. History of Gay Comics.”

“I always thought that just by virtue of getting a sense of Howard’s presence in the world of comics, I immediately started thinking of him as the Godfather of Gay Comics” said Rupert Kinnard (cartoonist, Cathartic Comics). “And so when I met him, I think I was a little concerned about whether he’d be accessible and approachable. And I just couldn’t believe how warm he was to me.”

“When I met him, I don’t know what I expected, but here was this quiet unassuming Southern boy, standing there,” said Diane DiMassa (cartoonist, Hothead Paisan). “But then I realized – he was so astute, he was standing there like a sponge, taking everything in.”

“I think it was in ’93… I had been reading Howard since my roommate in the early ’80s gave these comics, these Gay Comix,” Robert Kirby (cartoonist, writer, Curbside Boys, QU33R). “I was like, ‘WTF is Gay Comix?’ I felt like I had come home. I just ravished them, all four – he edited the first four issues, and they’re all classics, and they’re wonderful, and I wish they could get reprinted in a beautiful book or something. So when I got to actually meet him I was in awe and I was nervous. Also, would he be approachable, would he be this god-like figure? No, Howard, you could talk to him just like anybody else, he’s a Southern gentleman.”

From 1983 to 1985, Howard’s comic Wendel was printed in the Advocate. The story focused on gay community, an unprecedented theme in comics.

“You’ve got to remember that in the old days, gay people were kind of treated as victims or evil people in a lot of the media,” said Velez Jr. “Seeing a comic like that, where not only do they have a normal life, but they have concerns just like we do.”

Howard’s influence was felt across the world of queer comics.

“Reading the Wendel strips when I did was a great influence for me in terms of the community and the way I ended up creating a world for The Brown Bomber and Diva,” said Kinnard. “That was another way that I felt I was really influenced by Howard.”

“A lot of what Howard did, especially Wendel and Stuck Rubber Baby, came from his heart and his emotional state,” said DiMassa. “He outlined the struggles and his deepest feeling and what went on in his head, emotionally, and that really touches people. And also, it was one of the first places where we saw ourselves, and that’s always huge. You know, we’re gay, and some of us are of color, and where did we see gay characters? No where, when he started, and that’s always a break through moment.”

“I think probably the most groundbreaking part of that strip was that everything came from character,” said Kirby. “Things sprang more from their interiors than things happening to them. Although certainly things happened to them, a lot of outside forces – this is the Reagan years, which you know, you re-read it and you remember how hard those years were, how really difficult those years were.”

“One of the things that was so impressive about Wendel was that he included a very broad range of the gay community,” said Camper. “So he had female characters, he had characters of color, he dealt with things like AIDS and the Reagan world of politics. But it wasn’t like some of the early queer cartoons were very much one very small section of gay white men, and Howard really had a huge community in Wendel.”

Howard’s next big project was Stuck Rubber Baby. It took many years to complete and was published in 1995. The graphic novel is based on Howard’s own experience of accidentally producing a child as a white gay man during the 1960s in Birmingham, during the Civil Rights movement. The narrative weaves together the personal story of a gay man coming to terms with his own sexuality with the backdrop of the important period of United States history.

“I was like, ‘oh, this is going to be another story of a white man experiencing Civil Rights, right?’” said Velez Jr. “But then I read it, and I saw how he weaved his own coming out with the Civil Rights, how the people who helped him come out were people of color, how going to the Black gay bar was just such a huge experience for him that it kind of changed his life…”

“It just ended up blowing me away, because I thought that even when people of color appeared in the works of other queer cartoonists, sometimes the characters felt incidental,” said Kinnard. “I was really astounded how Howard really balanced those two communities – communities of color and queer people.”

“It’s no small task to meld his personal stuff with such a huge social backdrop,” said DiMassa. “He was just so good at it all – his draftsmanship, his consistency, and his storytelling abilities were off the hook.”

Panel 3 – Howard Cruse’s Legacy

The third and final panel focused on Cruse’s legacy. This portion of the presentation was moderated by Hall.

“My personal history is that in the 1980s when I was a college student, Gay Comix was one of my first exposures to the queer community beyond the limited experiences on my own campus,” said Ajuan Mance (cartoonist, professor, 1001 Black Men, Gender Studies). “And as such, the everyday-ness of the lives depicted in the various comics in Gay Comix was really remarkable, as were the diversity of comic creators. So it gave me a sense of how big the world of queerness could be.”

Mance also discussed the more academic aspect of Cruse’s legacy.

“As an academic, I really look at this pivotal moment, particularly in the 1980s, where people at the margins kind of capitalize on the fact that just representing the diversity of their experiences, just living in the regular lives without necessarily anything particularly heroic, is transgressive when they have been silenced in the past,” said Mance.

“My first exposure to Gay Comix was in the ’80s,” said Tara Madison Avery (cartoonist, publisher Stacked Deck Press, We’re Still Here, Resistance). “I was a closeted suburban teenager. Back then we didn’t have the internet and direct sales shops were afraid to carry anything that didn’t turn a profit for them… The only way I could get Gay Comix in the ’80s was mail order, and it would come to my house in a brown paper wrapper. And I was afraid that my parents would get to it first and have some sort of fit of curiosity and the gig would be up! But basically it was a sort of a message from outside of Overland Park, Kansas, that there are people who live their lives and they have different sexualities and different approaches to gender and life, and that was something that really affected me.”

Hall worked on a book called Theater of Terror: Revenge of the Queers with William O. Tyler, the last place Cruse was published during his life.

“Theater of Terror is filled with so many wonderful young queer creators, and they’re telling all these new stories,” said Tyler (cartoonist, editor, podcaster, Theater of Terror, Cinephilia). “And that’s all great and valid, but it was so rewarding to have a couple of the pioneers from early queer comics, including Howard Cruse, to be a part of this. You know, Howard’s work is still relevant and timely. Some artists are of their time or go out of fashion – that wasn’t Howard Cruse. All of his work is still very, very relevant right now to what’s going on in the world within queer communities and outside of queer communities, as well. So it was great that he was a part of this continuation of queer comics.”

“I kind of avoided his work a little bit when I was still coming out because I found Barefootz a little twee and people in their twenties can be really rigid about what is cool and what is not cool,” said Steve MacIssac (cartoonist, Shirtlifter, Unpacking). “I think I read Stuck Rubber Baby in the middle of my coming-out process. I came out late – I was twenty-six, and in a lot of ways my coming-out process and my coming-out as a cartoonist processes are very intertwined. Comics has this great ability to be this space to kind of figure out identity – they’re masterful places to work out identity issues, and I don’t know why. But I think that’s why so many LGBTQ people are invested in that space. And so for me, it was absolutely doing that, and his work was inspiration in trying to figure out who I was, and by extension, what the world around me was.”

Hall pointed out that Barefootz was made before Howard Cruse came out, and how his work “leveled up” once he became more open about his authentic self. MacIssac agreed, saying that Barefootz has the feeling of artifice in the way that his post-coming-out work does not.

The panelists emphasized how seriously Cruse took the responsibilities of building queer community, and the intense effort he put into making sure the voices of all creators could be heard.

“As an editor, he put that into practice,” said Hall. “He was sure in editing Gay Comix that there were creators of color, that there were women as well as men, and as far as I can tell, the first out trans comic by an out trans person, “I’m Me” by David Kottler, in I think Gay Comix #3, was in those pages. So he fought to open doors up for everybody, as much as possible. He was a community-builder in a way that’s really quite remarkable, and I think is felt to this day.”

The many panelists who were affected by Howard Cruse’s legacy had plenty more insights to share, and interested parties are strongly encouraged to watch the entire hour-long panel.

Miss any of our other SDCC 2020 coverage? Click here for much more!