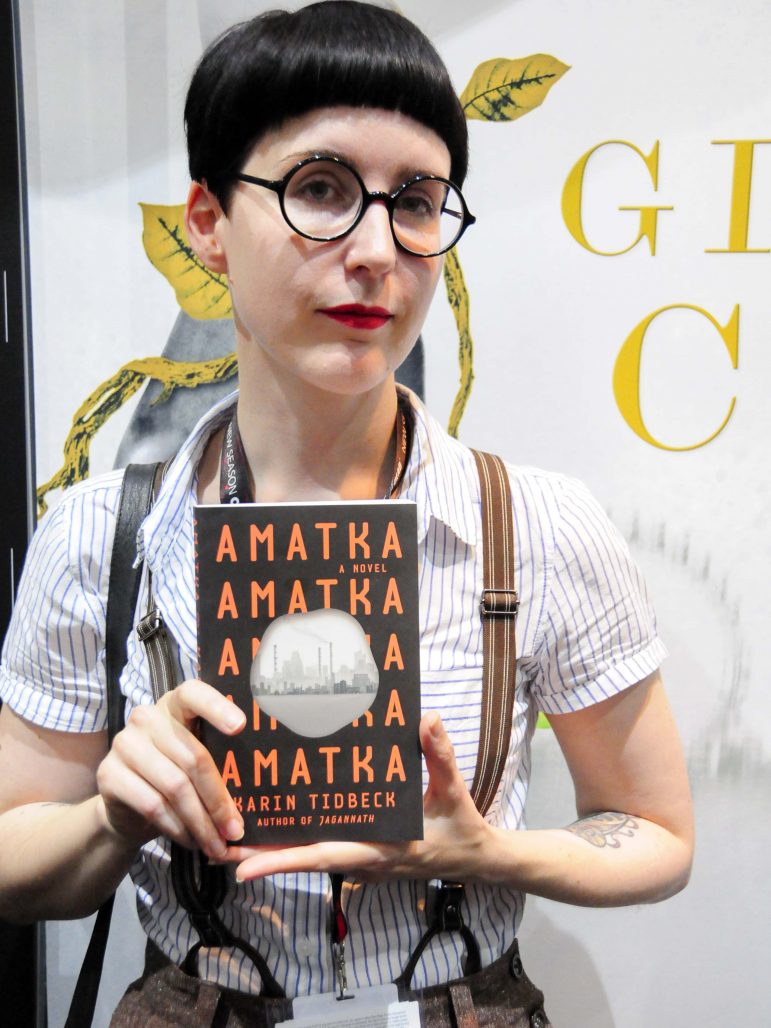

Karin Tidbeck is a science-fiction and fantasy author, born in Stockholm, Sweden. Her latest novel, Amatka, focuses on a colonized alien-planet where the physical use of words plays an integral part in the shaping and maintaining of the world. At this year’s San Diego Comic-Con, I sat down with her at the Penguin Random House booth and asked her a great many things.

–

When did you start writing?

I’ve always been writing. The first thing I wrote I was five-years old. It was an illustrated story called “Two Poor Children.” It’s a comic about two poor children that find gold and live happily ever after. It’s very consumerist.

Would you say you’ve always been into the fantasy and science-fiction genres?

Yeah, I’ve never written social realism. I’ve always written fantasy or science-fiction.

What do you find most appealing about them?

I see it as a huge laboratory. You can do whatever you want in science; You can try new concepts and new ideas, explore alternatives to the world that we live in right now. To me, it’s the best form of literature because literature needs to do something to you. It has to move you somehow, and what moves me is possibilities; new worlds.

Have you always planned on writing for an English-speaking market?

When I was nineteen, I worked in a science-fiction bookshop in Stockholm. There was, and still is, this magazine called “Locus,” which is the SFF industry’s main magazine, and I would read that during lunch break. And I had this revelation that “I wanted to be in here. I want to have my book reviewed in here. I want to have an interview here. And I want to be on the shelves in the book shop… in English.” The thing is, Sweden has a very small readership. It’s very difficult to get books published, it’s very difficult to sell books, it’s extremely difficult to sell speculative fiction. So, I realized that the market was so small that I had to switch languages, but I didn’t switch until I was in my early thirties.

Tell us a little about your book, “Amatka.”

Amatka is about humans colonizing a world where matter, physical matter, responds to language. It’s about what happens to society that tries to survive in such a world. What happens to the people who quite can’t find a place in it. So, it’s about reality, it’s about language, it’s about revolution, and it’s about love.

Would you say you decided to write this book because language and words are such a big part about your life?

It was a very organic process. It started as a series of dream transcripts that I wrote down when I was… well, fifteen years ago now. And I turned those into poems. So, I wrote a poetry collection based on dreams. That got rejected everywhere, so I used the material to eventually write Amatka. Ultimately the process took maybe five or six-years. But during the whole time I was constantly interested in this thing; “What if matter responds to language? How does language shape the world we live in?”

Amatka first was published in Sweden, about five-years ago now. How was the process from translating from Swedish to English?

I did a word-by-word translation to begin with and then I went through it as if it were a first draft of any book. I went through the language, reformulated sentences, because you can’t do a word-by-word translation of anything really. You have to reimagine each sentence as it is.

Were you afraid some elements of your writing would have been lost in the translation?

There were some difficulties when trying to carry them over into English. The Swedish [translation of Amatka] has no metaphors, or synonyms, or homonyms, because it’s not part of the Swedish language. Since they were “forbidden” in the book, I had to write them out of the prose as well. So, making that happen in English was difficult because English is a different language in that way. It’s difficult to tame when you’re not a native speaker, and I’m not a native speaker. I can [translate well] to Swedish; it’s hard to do to English. Swedish dialogue can be more direct that English is, so the way you shape the character or the impression of the character through dialogue is harder when you translate from one language to another.

Is there anything else you’re currently working on?

I’m currently working on a novel, which I can’t talk about because it’s not done. I have a few short stories that will be coming out in the near future, which I can’t talk about either because they’re also not done. It’s always an interesting question, isn’t it? You go into the world and show them your new baby. “Here’s my baby! Look at it!” And everyone’s like, “Okay. When’s your next baby?”

What ideas would you love to experiment with in the future?

I’d like to write more about gender structures and explore different modes of how think about gender, how we see gender, and how we experience gender. I would also like to write more about mental illness. Most of the stuff I read when it comes to mental illness is horror stories or very sad things. I would like to explore the subject in ways that doesn’t turn the sufferer, if you will, into the victim. It can be something else. I’ve done this in a couple short stories already, but I would like to expand that.

Do you think you’ll ever write exclusively for an English-speaking market?

That’s what I’m doing right now. I really don’t write in Swedish anymore because I can’t sell. It’s very difficult to sell. And if you do sell, you really don’t get paid. So, I write almost exclusively in English.

What advice would you have for readers, particularly young-adult reader?

Language is the ultimate power. Language is how we decide what the world is or what it’s going to be. And without language… If you don’t have the language, you don’t have the power. Reading anything really, because you don’t have to read the “Russian-classics” in order to be a reader. The important thing is that you read, because you arm yourself with words.

In a typical day, what is your writing schedule?

If I’m working on something new, in the morning I’ll write long-hand, meaning by hand, edit in the afternoon, and then do all the dull stuff I have to do. You know, email, invoices, and booking… When I read, I read comics and novels. Sometimes I’ll play video games or board games. That kind of stuff.

Who have been some of your writing influences?

Probably, since I was a kid, there was a Finnish author named Tove Jansson who wrote “The Moomins” books. Basically, she talks to kids about scary stuff, which opened my eyes to the fact that there’s darkness in the world when she made it so you could cope with it. And there’s Neil Gaiman’s “The Sandman” graphic novels that I read when I was a teenage and they were very important to me. Also, science-fiction by Ursula Le Guin, weird fiction by China Miéville, and some Swedish folklore as well has been very important.

Is there anything in particular you draw your inspiration from?

I really can’t say I get my inspiration from there, or there, or there. What happens is that I think of my brain as a compost heap. Everything I see, and experience, and then goes on the top, and it just ferments. What I write is basically what I scoop out from the bottom. You know, the garbage juice that comes out.

What do you love best about writing?

It is the best feeling. It is the best high, because it is a high, when you’ve begun to write something and you realize that this is something, that this could be big. You fall in love with it and you fall in love with the story. It’s a rush like nothing else. And you get hubris. You’re sort of the “I’m a young god, I’m on top of the world! I can do anything! This is amazing! I’ve come up with something that no one has ever come up with before.” And obviously after that you sort of fall flat and go “This is shit… I don’t know what I’m doing… Keyboards should be taken away from me.” And then you keep going to the next point which is “Okay, this could work.” Then you’re back to “I’m a young god, again!”

Comments are closed.