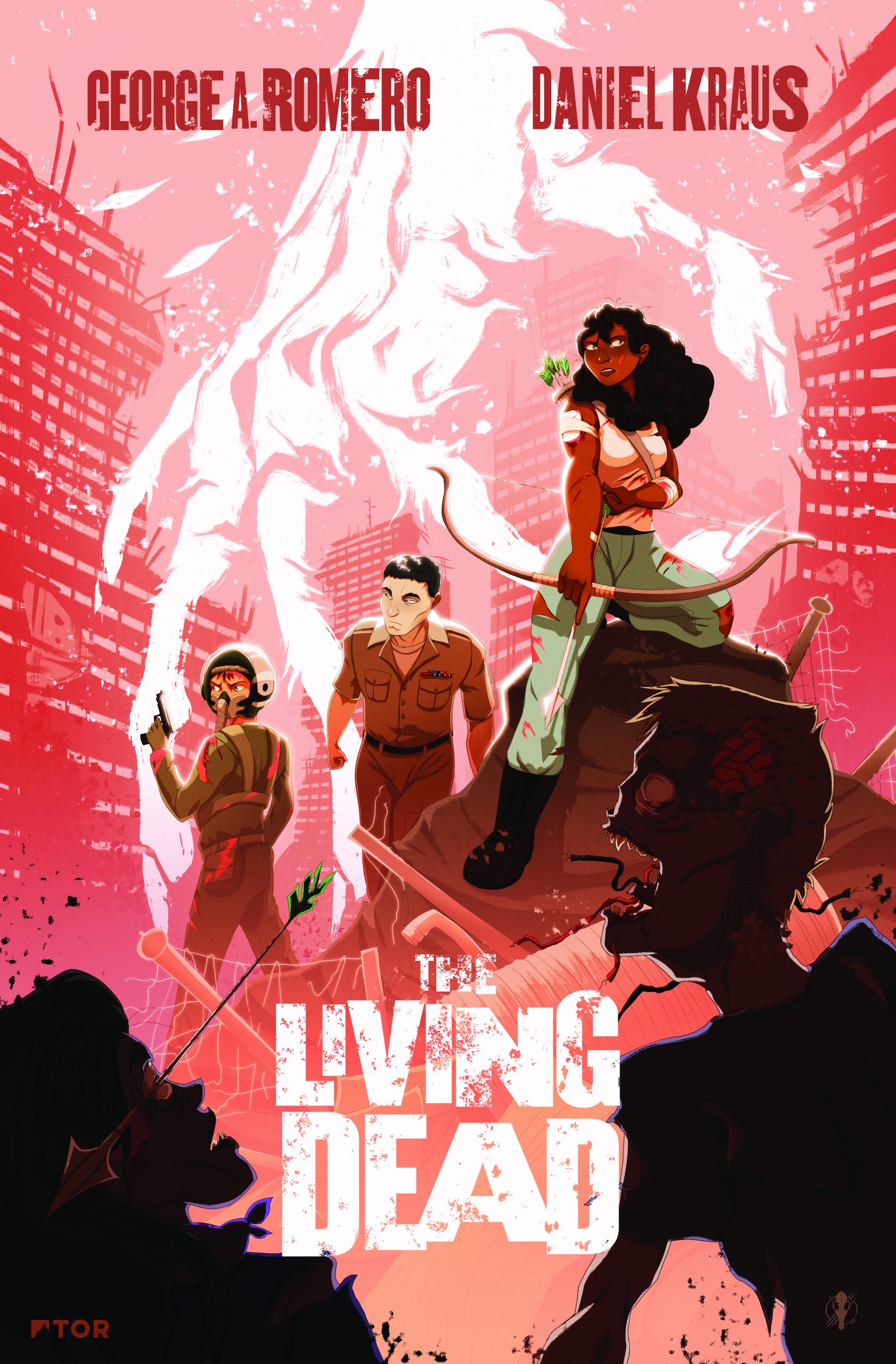

The Living Dead is the final word on the late George A. Romero’s Dead cycle, and the lengthy novel co-authored by Daniel Kraus delivers on the potential of using prose to raise the seminal class-and-capitalism-ravaging zombies.

Madrugada of the Dead

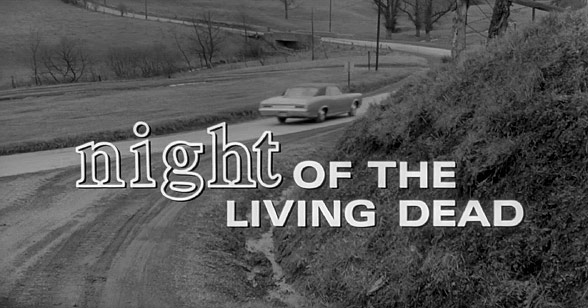

The Dead cycle began with Night of the Living Dead, Romero’s 1968 black and white horror film that follows a handful of strangers tossed together in a Pennsylvania farmhouse and left to fend for themselves against (in order from least to most dangerous): the undead, themselves, and a merry band of armory-toting racists who have self-appointed themselves the Brave New World Police.

However, something went wrong during the movie’s birthing process. When the original distributor of the movie changed the title from Night of the Flesh Eaters, the necessary © wasn’t included on the title card, and Night of the Living Dead ended up in land of the public domain.

The copyright blunder allowed Night to be played for free, and the ideas and images of the film stumbled their way into every corner of the United States via TV sets, movie theater screens, and even as stock footage in the background of other movies (themselves made by filmmakers who were heavily influenced by Romero).

The undead golems raised by Romeo became ubiquitous, but thanks to the missing copyright bug, he didn’t receive consummate compensation. That being said, without the failure to © the true name of Night, Romero (and by extension those lumbering, indefatigable undead ghouls) might never have achieved the notoriety that allowed him to make the movies he did manage to make during his life – a Crossroads deal if ever there was one, but one that we devoted Dead heads can all thank him for making.

Ultimately, the Dead cycle is comprised of six completed movies, released between 1968 and 2009, each of them offering a window into Romero’s singular vision for the World of the Dead. Nevertheless, throughout the decades, Romero stated that he was at work on a novel that would unify his stories in a way that proved elusive on film. That novel remained unfinished when he died while listening to The Quiet Man soundtrack in July 2017.

I’ll Take You Home Again

Romero’s career was filled with – and perhaps even defined by – fruitful collaboration. Beyond more obvious examples like Creepshow, making a movie is invariably a cooperative undertaking, and something about Romero’s creative process seemed uniquely honed to working with other talented storytellers, yeilding unbelievably mind-blowing results. Fortunately, this characteristic is one that evidentally cannot be diminished by the grave.

The Living Dead is borne of a collaboration befitting the man who raised the golem of the undead to haunt American media. Well after the late Romero’s agent Chris Roe had approached Kraus and work had begun on his portion of the novel, a significant chunk of additional manuscript was uncovered. For those curious about the gritty details of the collaboration between the late Romero and Kraus, a co-author’s after note is quite detailed about the surprisingly collaborative process, which I will largely avoid discussing considering it is closely tied to the novel’s plot.

However, one aspect of the preparation undertaken by Kraus, shared during a spoiler-free panel for the novel during SDCC ’20, illuminates how seriously the author took the job of writing the prose compliment to Romero’s films. By poring over the movies themselves, listening to interviews and commentaries, and digging through the comics and prose stories written by Romero, Kraus established a timeline for the Dead cycle and then used this to chart the arc undertaken by Romero’s Dead world. The result is a perspective that illuminates the themes and thoughtfulness that made the Dead cycle such a uniquely captivating story.

“We aren’t the only people on this island, and we all know it.”

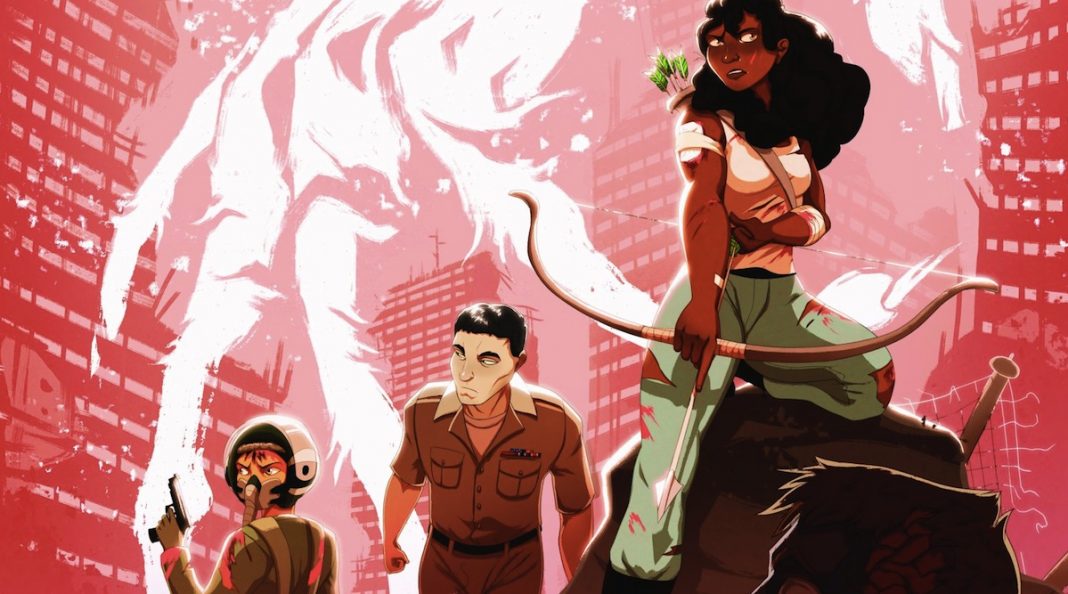

The characters that populate Romero’s Dead cycle are distinctive: archetypes for an undead-updated world that is only just beginning to understand what modifications will be necessary for the dramatis personae.

Just like the living characters that appear onscreen in the Dead cycle, those who appear on the page in The Living Dead are astonishingly… well, alive. They change over the course of the story, and while some rise above the shackles that have been placed on them by racism and capitalism, others attempt to use the trappings of our collapsing society to claim the control after which they have always lusted.

This goes for both the living and the undead, and I’m pleased to report that this particular variety of character is well represented in the book, just as they were in the Dead cycle. In fact, you even get a glimpse of zombie interiority in a way that was never possible through the medium of film, made all the more exciting by the fact that this element of the story was based on a short story written by Romero himself.

Beyond the perspective of the undead, the novel format also gives The Living Dead the opportunity to unify the many, myriad perspectives of its characters in a way that was only possible onscreen when considering the aggregate of all six movies.

The Lost Reflection

Language has always been integral to the Dead cycle, and few places in the movies make this more evident than the opening minutes of Dawn of the Dead (1979). “Come on, Martinez, show your greasy little Puerto Rican ass so I can blow it off,” spews a SWAT team member less than ten minutes into Dawn.

The Living Dead digs deep into the way language – especially racist labels and epithets – are used as a method of paving the way for violence.

The way that language is used as a tool for the living to oppress the living is also thoroughly examined in the novel, using explicit and bare terms. One example – particularly meaningful for me personally – comes when Jenny (remember that name), a fighter pilot, takes time in her dialogue to explicitly confirm that her statement that “all the women” are banding together to fight includes trans women.

Is it subtle? No, but considering even high-profile celebrities like She Who Will Not Be Named continue to use words to try and bury trans women, it is a necessary reminder that in a world where the dead remain in their graves, some of us have no choice but to haunt them while we are still alive.

The Walkin’ Dude

Also in these pages is a villain who can only be described as timely. Like Stephen King’s corrosive Randal Flagg, The Living Dead’s malignant Lindof is a slimly scourge who stands atop the Drumpf International Hotel in Las Vegas and casts a long shadow over the American Dream from one turn of the wheel to the next (say True, Sai Kraus, and say sorry).

Romero never shied away from depicting ugliness on screen, and that doesn’t just include the way the living treat one another (that boring, everyday evil embodied by Lindof and a million men just like him). But he also made sure that viewers were rewarded for sitting through long spates of listening to the living be awful to each other thanks to the inclusion of unforgettable scenes of zombies ripping the living to shreds.

What Dead movie would be complete without a good old-fashioned gore orgy? The Living Dead understands that this visceral component is indeed an integral part of Romero’s Dead world, and it is included in appropriate proportion for the book’s 630 pages. While the Dead cycle’s gore may have achieved cinematic perfection thanks to Tom Savini’s unique abilities, The Living Dead replicates the requisite sensation by ensuring that the evisceration of the living is often described in culinary terms.

It’s an example of how, rather than merely attempting to ape what had already accomplished onscreen in the Dead cycle, The Living Dead attempts to achieve the goals that Romero had hoped might be uniquely possible through prose. Among these possibilities is an expansion of scale: the novel’s narrative follows multiple characters on journeys that begin in various places around the United States before beginning to arduously stagger toward one another.

Another is budget. During his life, Romero had to constantly hustle to scrounge up the necessary funding for his cinematic vision, frequently being forced to abandon ideas deemed too costly to bring to fruition (such as the undead rats in the script for Land of the Dead). The medium of prose can tell the tale of a Black teenage girl fighting for her life in a Missouri trailer park just as cost effectively as it can show you the enraptured crew of an aircraft carrier watching a perverted power-crazed Catholic chaplain survive a Long Walk across a deck filled with the wreckage of burning fighter jets.

“The brain is the engine… the motor that drives them.”

The Living Dead is a meticulously structured novel. Kraus states The Tales of Hoffmann inspired The Living Dead’s “three-act” form. Seeing as the 1951 movie is cited as the First Mover of Romero’s miraculous cinematic career, and to help channel his voice, Kraus studied not just the Dead movies or the movies Romero made in general, but also the movies that themselves inspired Romero.

(A brief aside for an example of the synchronicity that permeates The Living Dead from its construction to its content: the movie Hoffmann is based on an opera by Jacques Offenbach, who died four months before the opening, manuscript in hand, having shortly before written a letter to a friend imploring that his opera be staged before his death.)

But while Hoffmann may have heavily inspired The Living Dead, the novel is constructed like a brain, with the two hemispheres of Kraus and Romero joined together by the corpus callosum of Hoffmann/Hoffmann (the former being the character who bears both that name and an important narrative function in the novel; the latter being the work of art through which Kraus was able to unify his artistic vision with that of the late Romero).

Where, then, do the movies that comprise the Dead cycle fit in with this brain-based reading? The movies are the urschleim, the protoplasm in which the brain is suspended (and a concept brought into The Living Dead by way of an allusion to The X-Files). The Living Dead never attempts to usurp Romero’s movies, but rather, it exists as a counterbalance alongside them, reflecting many of the themes, stories, and characters in illuminating and interesting ways.

“Our responsibility has ended.”

On a particularly heartbreaking page of the author’s note that follows the novel, Kraus lists some of the projects that Romero had been attached to over the years that never achieved completion (including one titled City of the Dead, a name that makes my broken heart flutter).

Regardless of the heartbreak of what might have been, we can nevertheless rejoice for what we got. Both the Dead cycle and The Living Dead are indispensible texts, unflinching examinations of who we are, and – when all the words are said and done – a whisper of hope that someday our efforts might plant the seeds of a better world for those who will rise after we have died.

“During his life, Romero had to constantly hustle to scrounge up the necessary funding for his cinematic vision, frequently being forced to abandon ideas deemed too costly to bring to fruition (such as the undead rats in the script for Land of the Dead).”

A lot of that came from Romero’s desire to make his movies his way. DAWN and DAY could have been big-budget, major studio releases (Universal was interested) but Romero would have had to tone down the gore so the films could receive an R rating.

He declined to do that, so the films had to made cheaply and independently, and released without a rating. They still look better than a lot of expensive studio films!

Comments are closed.