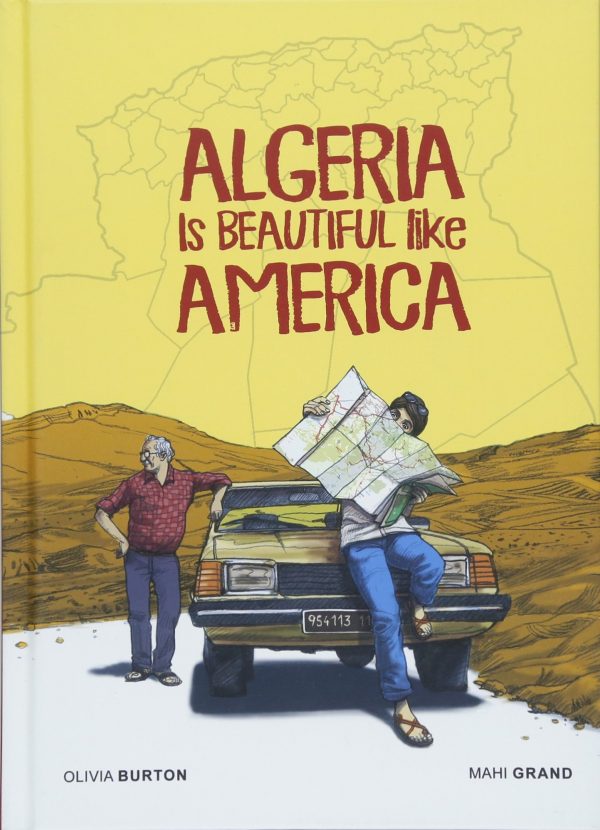

And the personal story is the point of this. Author Olivia Burton’s journey is one of chasing what might be an idealized past in the hopes that some of the familial fairy tales told to her as a child are true, but through an adult gaze that offers clarity about her family’s real history in context of the region, rendered through Mahi Grand’s friendly artwork that makes an imposing journey seem less daunting and even welcoming.

Burton’s family was what is referred to as Pied Noir, or “Black Feet,” people of French descent who were born in Algeria. France controlled Algeria from 1830 to 1962. After Algeria gained independence, 800,000 Pied Noirs left the country, and this number includes Burton’s family.

A family memoir from the point of view of being a Pied Noir is a little tricky — in this conflict, they are the colonists, and were typically considered to make money off the hard work of native Algerians. There is resentment between the two sides of Algerian culture during this period, no surprise, and Burton has a major challenge in stirring up reader sympathy for her family and following the narrative path of uncovering the story of what some would consider oppressors.

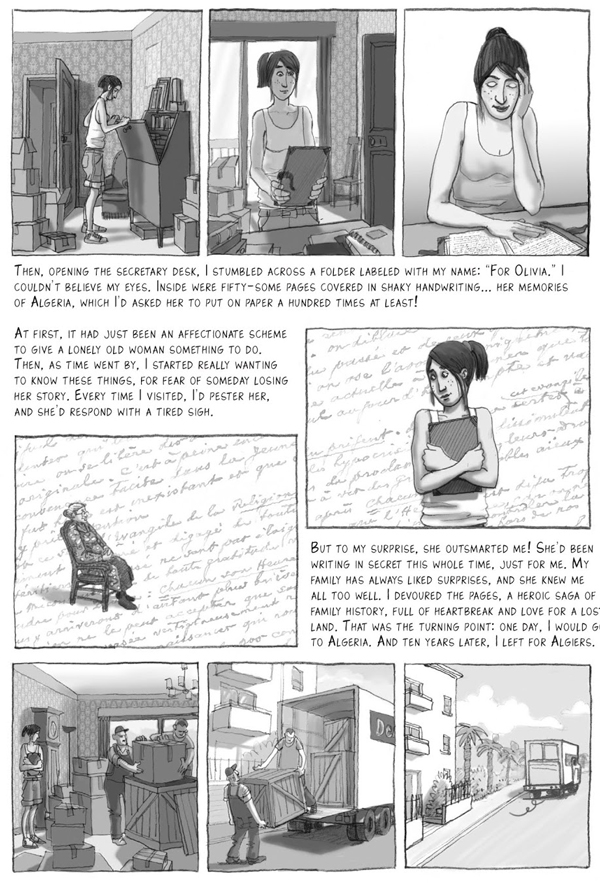

Burton does this by closely focusing on her own quest, which places her personal thoughts and reactions at the center of revelations about her family. This becomes less about documenting the Algerian life and times of her family and more about her coming to terms with what it means to be a Pied Noir. Like Nora Krug’s Belonging, an exemplary memoir of her family’s involvement with the Nazi Party, Burton’s story becomes in some ways a chronicle of oppressor’s guilt a couple generations later and examines the question of responsibility — that is, what are you required to do in response to the actions of your ancestors?

Specifically Burton acknowledges racist tones toward Arabs coming from her family, and the complicated vibe of their desire to be recognized as coming from Algeria, but not being mistaken for native Algierians and not being pitied as refugees upon their arrival in France. It’s part racist, part classist, and all indicative of the dynamics at play. And Burton, who dreams of the Algeria of her grandmother’s description, is at odds with the fact that her childhood dreams of her family are wrapped up in these negative views of the marginalized. It’s a position so many Europeans and Americans find themselves in.

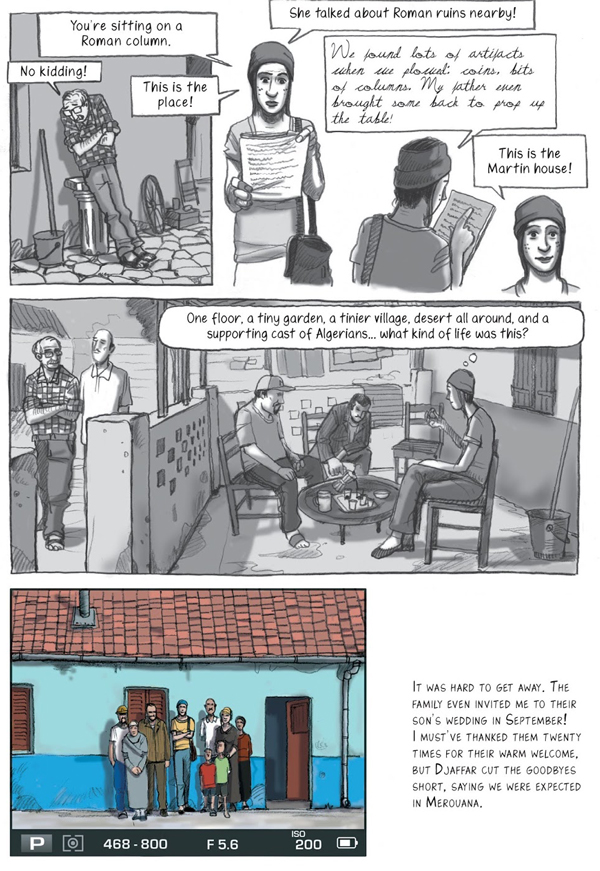

Burton does the most she can do, I think, and that is to visit Algeria and retrace the places her family lived. One difficulty is that though they started out in the city, they moved to the middle of nowhere and this requires that Burton get some help in her travels. At first, her attitude is typical of a modern Westerner, that form of haughty “I can take care of myself” huff, which also translates into the statement of a woman standing her ground and not wanting to appear frail, especially to her family. But the necessity creates some of the best parts of the book since that is where she steps outside of her family fantasy and into the real world of modern Algeria, where she interacts with actual people who live the lives that are only family lore for her.

Burton is initially combative with her guide Djaffar — he is admittedly an overbearing and pushy guy upon first meeting, but he also becomes the gateway to the country opening up to her. As the book shifts into more of a travelogue mode, Burton by way of Djaffar’s efforts accesses parts of Algerian rural culture that she might not have traveling alone, including one personal to Djaffar that offers unexpected revelations and intimacy involving Djaffar that rewards Burton for sticking with him.

But at its root, this book is about rectifying personal lore with real events, and Burton comes to the conclusion that these might not be as perfectly alignable as she’d hoped, nor mutually exclusive either. The conclusion, as it almost always does, falls somewhere in between, with plenty of unknowables presenting themselves amidst some honest, heartfelt depictions of warmth.

In the end, I don’t know that Burton truly gets to the root of what her culpability in history is, nor necessarily how the stories the family tells themselves is a way of idealizing a complicated history, but I do know that as these journeys go, Burton is at least off to a very good start . She’s looked in the mirror and accepted the harder parts of any revelations, as well as the shortcomings of her family’s perceptions, and that may not be everything, but it’s surely not nothing either.

Comments are closed.