Necrosoft Games’s Demonschool feels like picking up a game from a Blockbuster for three days, returning it, and then bring it up on social media 15-20 years later as a hidden gem.

Back before algorithms and influencing decided what was trending, it was much easier to engage in crate digging—the process of digging through crates and bins at record stores for lesser known music. This practice applies to all kinds of media, even video games. You could happen upon something life-changing on accident.

Demonschool is a tactical RPG inspired by the first two Persona games in tone, humor and gameplay. I could just call it “gay Persona 2” and call it a day, but that is selling it short. Demonschool is a love letter in every sense of the word, from the music being inspired by ’70s Italian horror (especially Fabio Frizzi), to the writing being a send-up of Buffy, to the number of Y2K-related jokes, to the very obvious Persona 2 influence. Also, special shoutout to being an E-40 joke in the year 2025. They know ball over at Necrosoft.

Demonschool’s story follows Faye, the only demon hunter left on Earth in her first semester in college. (Yes, attending college. In an RPG? A concept indeed.) She was told by her grandfather that an apocalypse was coming by the end of the 1999 and she has to stop it.

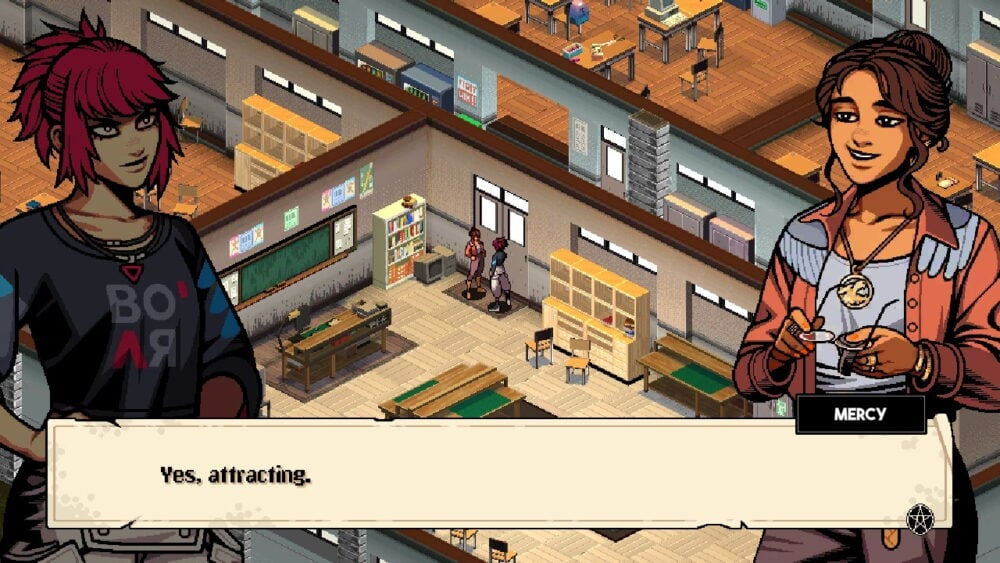

Along the way, she conscripts a Captain Planet-style diverse cast to help her kill the encroaching demon hoard and stop the apocalypse. Each of them represent discrete Y2K-era archetypes. From animal lover Mercy, to pacifist Knute, to dumb jock Destin, to not-goth-but-absolutely-a-baby-goth Namako, you will find just about anyone you’re looking forward to seeing in the cast of 15 (yes, 15).

But the thing that sets Demonschool apart from other titles apart from its massive cast is its messaging.

Demonschool focuses on real community building

I have been routinely disappointed by games that espouse progressive ideals and feature diverse representation, but don’t carry through that promise in their stories. For example, Hades 2 goes to great lengths to establish a matriarchal society hellbent on killing a world-conquering patriarchal tyrant, only to undercut its story by intervention of a male character in final act. The initial ending was so controversial that it was updated not long after the game’s full release. At time of writing, I have yet to return to it after playing over 300 hours in Early Access because of the ending.

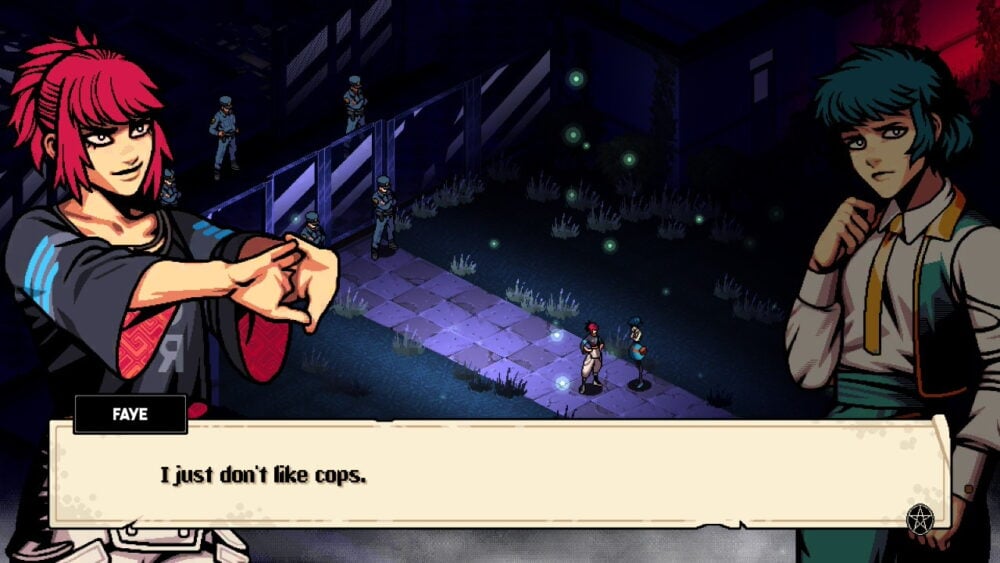

Demonschool, on the other hand, is casually and thoroughly progressive. The main character, Faye, is openly queer (and a pussy magnet in a way female characters rarely are), openly hates the police, and has a bone to pick with authority in a way I found charming and often hilarious.

So often progressive characters are written as caricatures of the ideologies they espouse by those whose ideologies better fit the mainstream idea of left-leaning. To be anti-cop is too extreme, even when faced with police violence. To see the humanity in criminals and have a nuanced view about the sociological position of gangs is too extreme. To feed people without demanding arbitrary labor requirements is too extreme. To even suggest that academic institutions are built to elevate rule-followers and uphold the desires of the wealthy to the detriment of others is too extreme.

However, Demonschool throws up a middle finger to all of that. It establishes early on that cops are not to be trusted, often instigate violence, and protect the powerful instead of the powerless. It is community-focused. Instead of Faye being viewed as a savior, she is a catalyst who uses the knowledge she wields to guide others. What makes her different makes her powerful. The game calls how she uses that power into question multiple times.

Without getting into major spoilers, Demonschool and Hollow Knight: Silksong (and boy do I have some thoughts about Silksong) offer some of the most layered messaging about the nature of dominion and domination from a woman’s perspective that I have seen all year. Both games thoroughly dismantle the idea that “feminine” ways of liberation—i.e. liberation achieved via communal work and not via domination and competition—are somehow unrealistic or obtuse.

There’s an entire week in Demonschool where the main goal is engaging in community care and mutual aid after the island town’s resources are hoarded by the police, an act reminiscent of the aftermath of natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina.

There is also a telling moment in which the scenario writer, Brandon Sheffield, seems to be referencing the organization Food Not Bombs and the number of times its members have been arrested.

In this scene, Faye is helping to feed the people when the cops show up, harass her and her friends, and instigate a fight with them. Following the incident, Faye and her friends continue their efforts to feed the town even during martial law. They use an old farm that was able to feed the whole island until outside forces tore it down and forced reliance on resources on the mainland (Hawaii and the American Samoa, anyone?). They repurpose a nuclear bunker built by the wealthy for a medical bay.

Throughout the story, the message is clear: The old ways will lead us to the apocalypse. The only way to avoid it is to leave convention at the door.

Critiquing Demonschool

Demonschool’s ending is rather abrupt. When the story ends, the game ends. There is no additional after credit scene or photos of where the characters have gone since preventing the apocalypse, which I would’ve liked. I would’ve loved to see what happened to the island after the apocalypse was stopped.

If the main critique I have about a game is that I wish there was more of it, that’s a very good thing. After all, I’m in the middle of my second playthrough. I wish there were more games like Demonschool that weren’t afraid to swing for the rafters in terms of their politics, especially right now.

Demonschool is available on PC, Switch, Xbox One/Series X/S and Playstation 4/5.

Correction: A previous version of this post critiqued the relationship between Faye and Namako for being strictly platonic. Upon publication, Necrosoft Games informed The Beat that Namako is asexual and aromantic, but “isn’t directly aware of it and doesn’t have the vocabulary to express it. Faye (being much more attuned) doesn’t ever broach the subject and loves her as a companion rather than as romantic potential.” We apologize for this error.