By Ricardo Serrano Denis

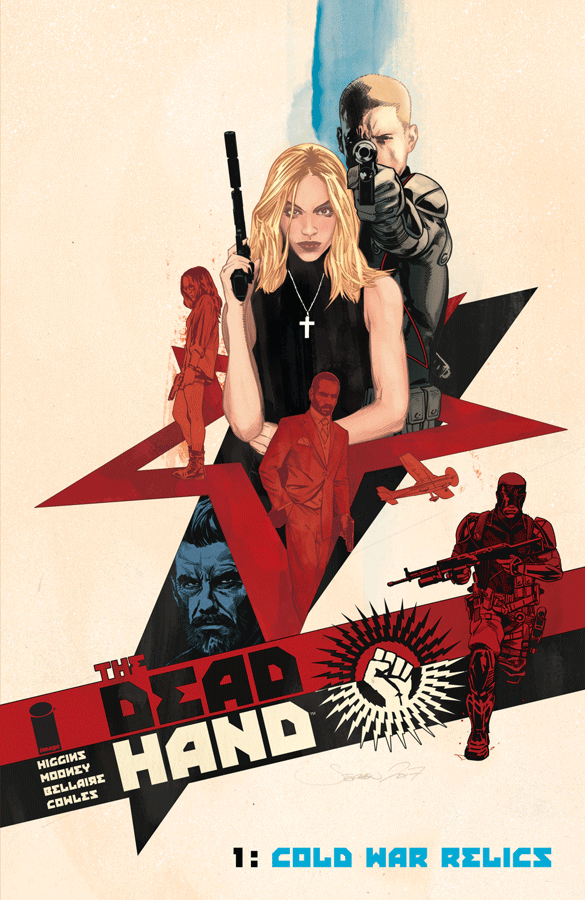

Kyle Higgins’s Dead Hand, illustrated by Stephen Mooney with colors by Jordie Bellaire, takes the Cold War and wraps it around secrets that can survive the fall of the Soviet Empire. It’s a story that contemplates the consequences of creating apocalyptic weapons and what would happen if said weapons came attached with a conscience.

The comic is now collected in a single volume, titled Cold War Relics, and focuses on a small town shrouded in mysteries involving spies and weapons in an alt-history Cold War world. We see teenagers demanding information from their spy parents while displaying an aversion to complacency that results in small town politics threatening to expose secrets that could end the world. While certain spies struggle with their secrets, a Cold War weapons program called the “Dead Hand” moves closer to the reality of a “mutually-assured-destruction” scenario that would end life as we know it.

I sat down with Higgins, at his booth (K28), to discuss influences, the research process for writing comics, and whether creators have the responsibility or not of creating informed readers when stories turn political.

Ricardo Serrano: So let’s talk influences. I’m interested in what inspired your idea for Dead Hand. I think I managed to get a little of Metal Gear Solid infused with John Carpenter movies while reading the book.

Kyle Higgins: Yeah, it’s definitely a collection of some of our favorite influences. Stephen and I decided we wanted to do a book together before we had a story. We specifically just talked about all the cool stuff we liked, like Metal Gear Solid, war spy stuff, [James Bond], John le Carré novels. From there, I just started building out this crazy world. I know a lot about Cold War history, well, I know enough about Cold War history. I knew about the Perimeter defense system and that the Soviets toyed with building a [semi-autonomous weapons systems designed to retaliate against the US] and so thought it was an interesting kind of setup.

From there it’s just thinking about surprising ourselves at every turn, trying different things. Everything about the book down to the way that I wrote it with voice-over is different from everything I’ve done before, so we were just trying to experiment. At times, Steven would draw pages before I written the scripts, you know, and then I would make it work in the script with voice-overs. We like those kinds of collaborative challenges.

Serrano: Oh, so it was kind of like a Marvel Style approach?

Higgins: Even less than that. Like, some of the double-page spreads of the origin backstories Stephen would just draw and then I would write their origins from that. Stephen is a fantastic writer himself. I never saw thumbnails. I would write the script and then he would turn finished inked pages. And sometime really different, and then I would just rewrite stuff. He would make changes if he really needed to, but 99% of the time we didn’t and it was fun to work in a backwards way.

Again, we’d been making comics long enough that we feel comfortable playing around with the form and the process.

Serrano: So, in terms of the politics of the comic, were you worried about how people would take to some of the topics, especially the parallels they could draw up from your story with current affairs? Is there something you wanted to specifically say with Cold War history?

Higgins: No, I mean, I started writing this book around two years ago. Some two and a half years ago. So the world was a very different place then than it is right now but we didn’t change anything. The book become, as you’re kind of alluding to here, more topical and timely.

What I’m more interested in talking about the ideas of optimism and hope, and things that as I find myself getting older I find it harder and harder to have the level of optimism that I had when I was a younger person and as a child. And I’m fascinated by the way we change in our perception about life and the world as we go through kind of, you know, the hard stuff which is living. So I wanted to say something about that and explore it to the length of the next generation. The Cold War stuff was the vehicle to do that.

Serrano: So on history, one of the things I like about your work is that they feel well researched. Do you think that you as a writer have a responsibility to inform and let the reader in on the history that’s servicing the story?

Higgins: It’s all in servicing the story. I research as much as I need to for the story. I’m not someone who spends months researching something at the expense of writing it, you know? I research as I go and as I need to in order to feel like I have a solid handle on the topic to write the narrative I’m interested in.

Serrano: I’m a History teacher myself and I’ve used Dead Hand in class. I’ve also used C.O.W.L. when teaching what a worker’s union is and so on. Is the pedagogical potential of your comics something that you’re interested in or is it something that scares you?

Higgins: Yeah, that’s awesome. It does scare me a little bit. It makes me worried I didn’t research enough, you know, in that context. I mean, [what I write] is a heightened form of historical fiction with an emphasis on heightened, you know? It’s not like what Erik Larson does — the novelist, not the comics writer — where he’ll do things like Devil in the White City or his book about the Lusitania, it’s not designed to be, like, super specific history or historically accurate. I like to be historically accurate when I can because I think it does land an extra level of verisimilitude to it all. But I try not to do it at the expense of telling the story.

Serrano: Would you say Dead Hand is a comic that’s really close to your heart?

Higgins: No, I mean, they all are. You just finish the story and it’s a little bittersweet, and then you move on to something else, but having the trade paperback for it, I’m really proud of how it turned out. I’m really excited that it’s been resonating with people the way that it has.

Serrano: It really has. Thanks for the chat!

Higgins: My pleasure, man.