Have you ever said: “yeah I could probably afford to cut down on my screen time.” Or maybe “I think I’m on Twitter too much haha.” Do you regret doomscrolling? Are you binging TikToks before you go to bed and cursing yourself the next morning for being up so late?

I’m sure everyone can relate on some level to the idea that they are perhaps overusing certain technology. And in my experience, it’s not difficult to get even the most casual tech user to accept some fault in wasting too much time on one app or another.

What’s infinitely more difficult, however, is helping others to understand that the technology in question is the thing making you overuse. That phone in the palm of your hand is what’s making you stare into a screen, making you post, making you scroll endlessly, making you binge videos that are “only 30 seconds.” On android devices, if you hit the back button on TikTok, it doesn’t exit the app, it refreshes your For You Page. You have to double tap it to leave, or hit the home button. That doesn’t sound like much, but that subtle difference in convenience is what turns controlled engagement into “just one more video and then I’ll sleep…” Obviously we could all afford to spend less time on our phones. But our phones, and in particular our apps, are built with the explicit purpose of forcing us to use them as much as possible.

Online statues, read receipts, push notifications, tagging, liking, favoriting, local news updates are all actively designed to make you turn your screen on and engage with an app. In fact, we don’t even have to turn them on in a traditional way anymore, not when most devices have always on displays. You may have set your phone down, but when that little social media notification pops up, you’re right back to scrolling, watching, posting endlessly.

Social media is by design a form of mind control, and Mindset is explicitly about a mind-control app.

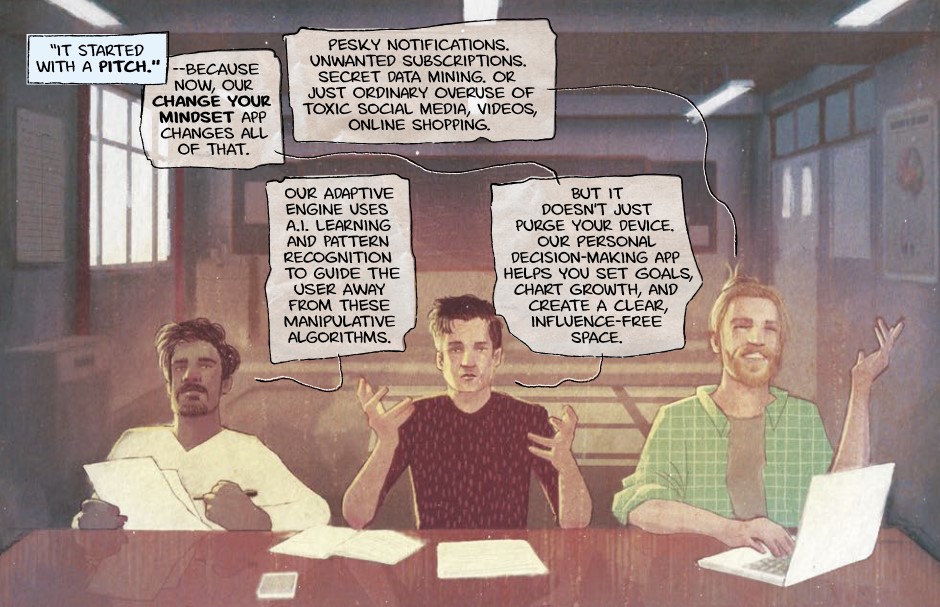

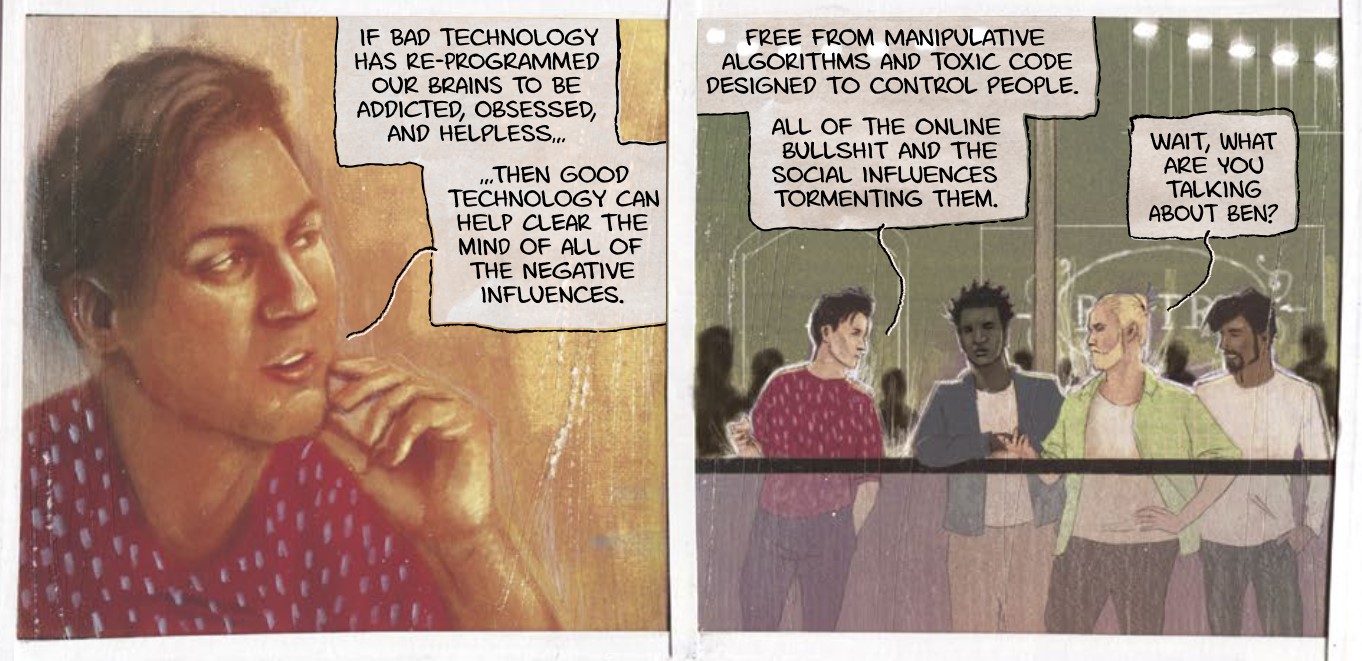

Mindset, a 6 issue miniseries by Zack Kaplan, John Pearson, and Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou from Vault Comics, follows Ben Sharp as he and his fellow college students attempt to strike it rich in Silicon Valley by designing an app to free us from the influence of apps, but inadvertently discover mind control.

By this point, there is extensive literature on the ethics of tech companies, on the psychological effects of avid social media use, on the philosophical questions surrounding our relationship to technology, and the history of how we found ourselves consumed, seemingly overnight, by performance and online clout chasing. There is also no shortage of dystopian futures and horror stories inspired by the rampant use of specific pieces of technology. The Department of Truth, for example, wrestles with the notion of truth in a digital age. Her (2013) presents a study of how we grow less human just as technology changes what it means to be human.

However, we don’t often see stories that strike at the heart of the horror right in front of us. Technology gone wrong is as old as time, but the technology itself being wrong is decidedly more rare. Thus, Mindset is a uniquely captivating series because it presents the implicit goals of tech bros into explicit dangers, and it paints a horror story of existence in a technological society well before the titular mindset app is introduced in the story.

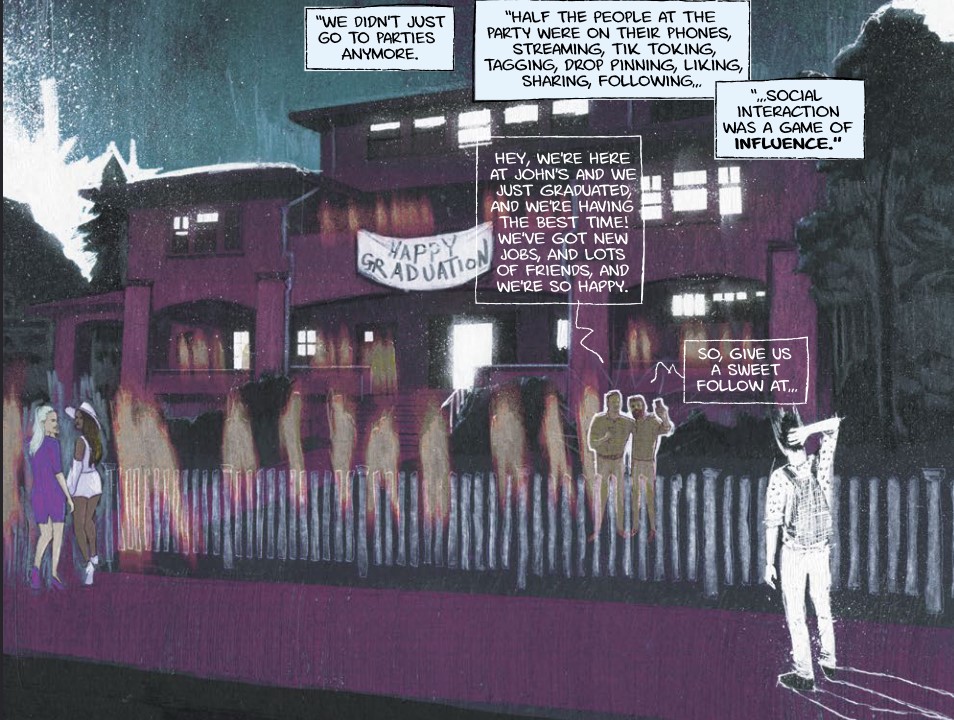

In just the first page in Mindset, we’re presented with the utterly bleak horror of a life in service to technology over humanity.

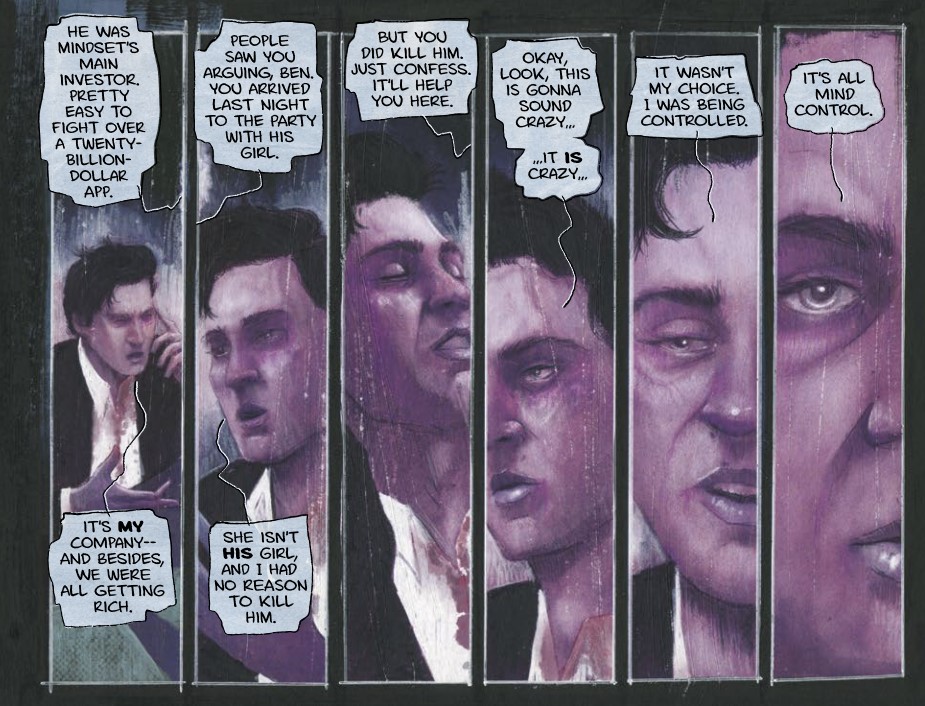

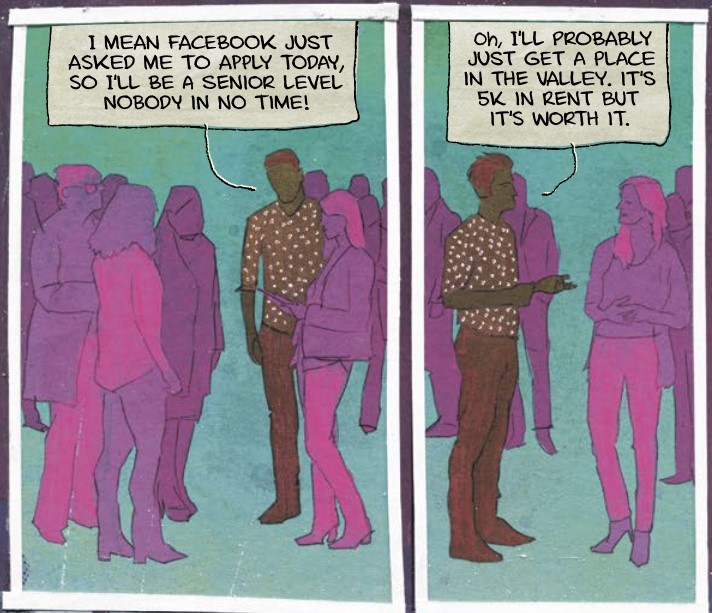

Pearson’s art reflecting the closing walls around Ben, the uneven lines of the panels, and the sickly purple/blue colors tell us this is not a propagandist success story, this is a Twilight Zone style journey through the morality and psychology of what drives tech ideology.

Mindset is a book about the horror of a life lived through a cell phone screen. The light blue tinge of Otsmane-Elhaou’s letter, the faded boxes of everyone outside your own head creates a distancing effect that keeps the story feeling like the world around us isn’t really there. There’s a disconnect from the tech ideologists and the world they’re attempting to shape. But more than that, even their own dialogue feels hollowed, literally backed by nothing as it floats into the air in a sea of jargon and expectations.

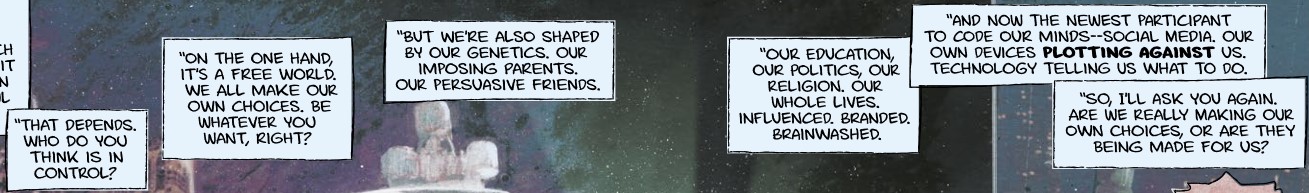

Kaplan opens by asking us a very simple question: do we feel like we’re in control of our lives?

The answer, of course, is that we’re not. Personal responsibility for tech use can only go so far when you’re up against a hydra of things that you cannot control, and that are designed to control you as much as possible.

And our protagonist in Mindset, Ben, agrees from the get-go that technology is suggestive, controlling your mood and priorities. And like a good acolyte of silicon values, his solution to this problem is the in the form an app:

His perspective is indicative of how entrenched technology, apps and smartphones have become in our culture: a book that opens with several pages of Ben musing about the nature of technology’s control over us leads us directly into a moment where Ben’s solution is just more technology. The difference between his app and any other on the market is that it acknowledges its goal of mood alteration, which is meant to make it seem benevolent rather than hopelessly misguided.

The quintessential problem with tech companies is that things that are not traditionally considered problems become problems that ought to be solved, and the only way to solve them is with new tech. This then creates a new problem by virtue of the technology in question, and can only be solved by more tech. And along the way, as problems are being manufactured, and solutions are being pitched to a boardroom of investors, specific design choices are made to ensure prolonged use, rather than the ostensible goal of problem solving. Take for example Venmo.

Why does Venmo need a timeline?

Like 70 million other users, when I go out with friends, when I ask someone to pick something up for me, when we split a pizza or movie rental, I say something like “I’ll venmo you.” Venmo, an app owned by PayPal, lets users transfer money to each other, allowing people to pay and charge for services without needing to use cash, Western Unions, or costly bank transfers. It’s just easier in day-to-day life to venmo my friend $10 for a movie ticket, rather than coordinating everyone buying tickets at the same time to guarantee seats next to each other.

But Venmo has a social media timeline.

If you open the app now, you can scroll through the various purchases and charges your friends have racked up over the last few weeks. I can’t really tell you why I need to know Christy paid Kaitlyn for tacos on September 6. But it’s all there, and if someone wanted to stalk you, steal your information or build a picture of your private life by just scrolling through Venmo, they can.

And someone already has.

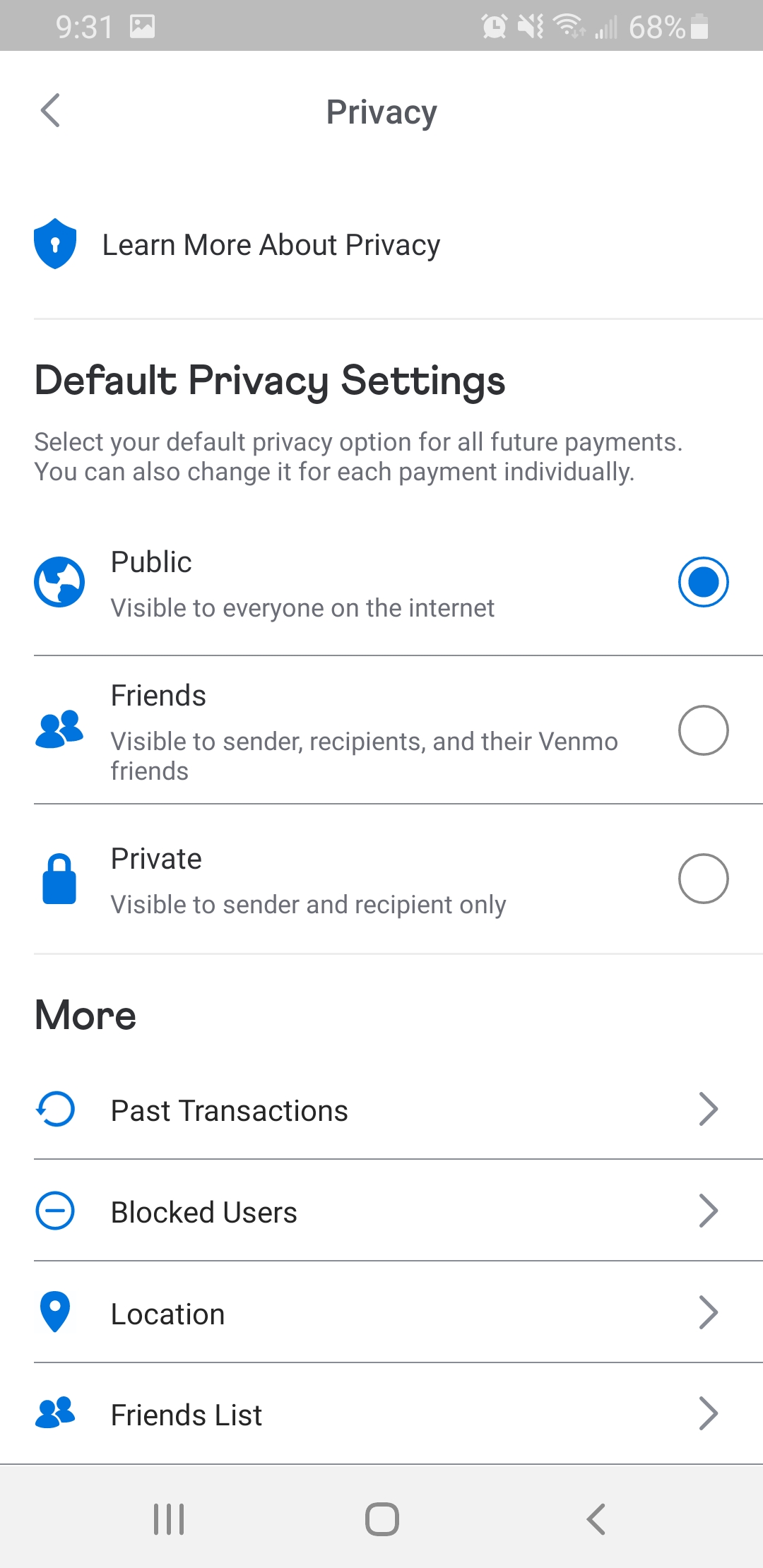

The app defaults all transactions to “public,” meaning anyone can see what you spent money on and who you paid. In 2018, several outlets reported security breaches possible through Venmo:

“I wrote up a quick, 20-line Python script and started scraping the API from two different IPs. Even with a rate limit in place, which limits the speed at which a single IP can make requests, I could download 115,000 transactions per day. Every few weeks, if I had some free time, I’d start the scrape again, cleaning the data and feeding it into a MongoDB database.” –Dan Salmon, Wired, “I Scraped Millions of Venmo Payments. Your Data Is at Risk” 2019

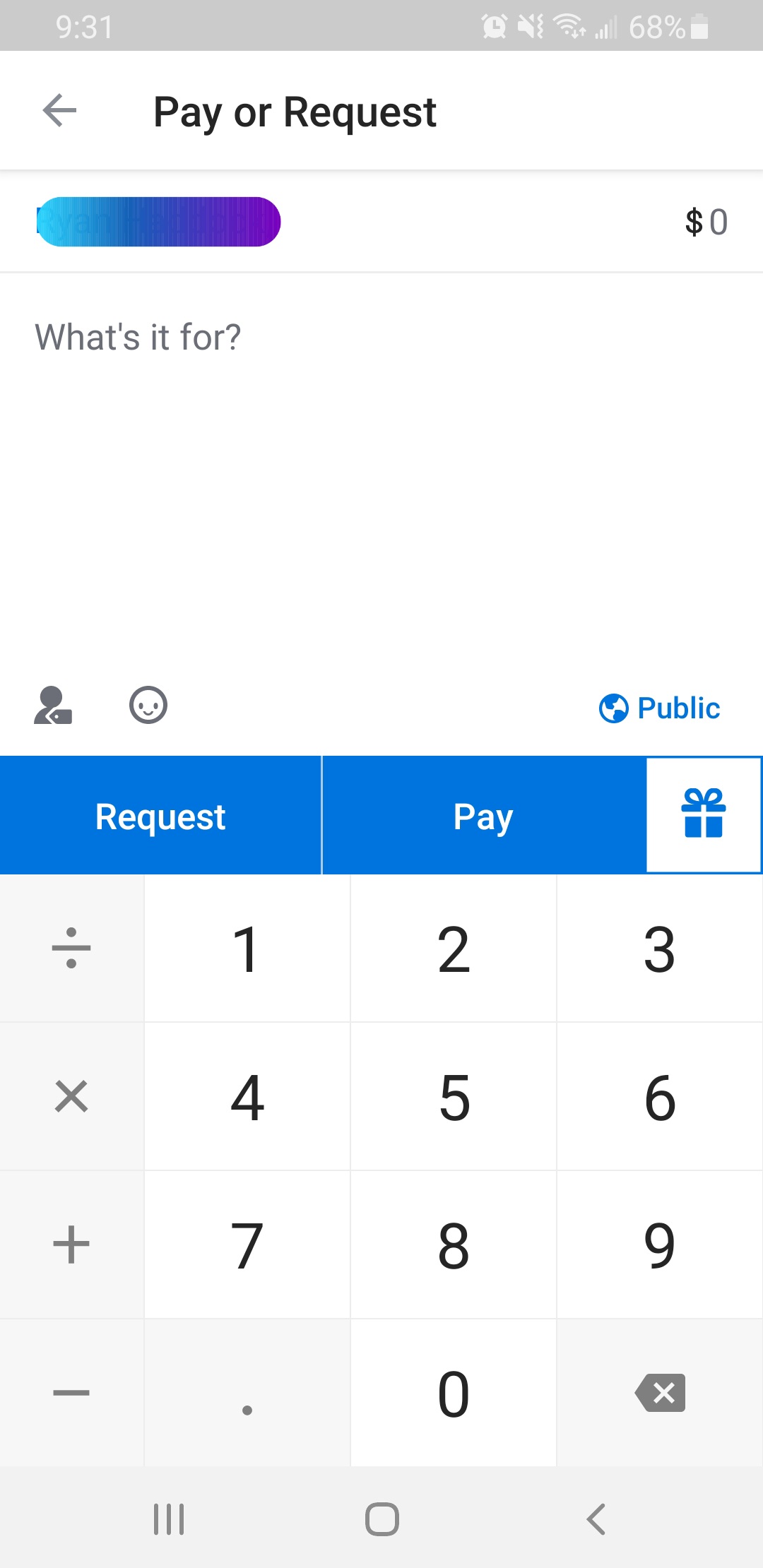

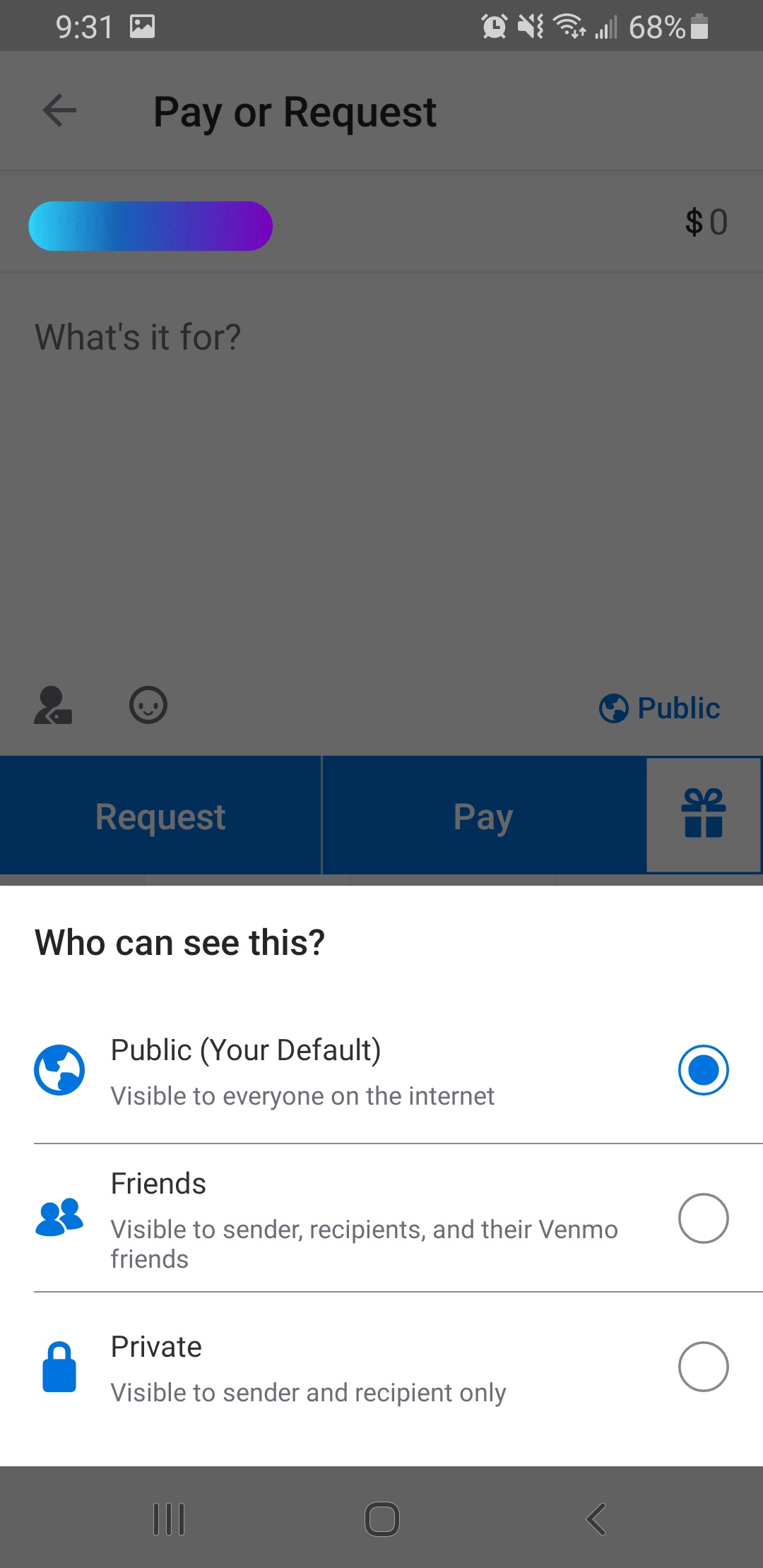

A user when making a payment or issuing a charge through Venmo will have a pretty easy time finding the person, entering the amount and specifying which payment account the money is coming from.

However, each and every transaction is by default “public,” and the user has to find that tiny little button, hidden above the comically larger “REQUEST” and “PAY” buttons in order to change the setting. This has to be done every time unless you go to settings, privacy and select your default privacy setting.

An attentive and mildly tech savvy user can adapt to this without much effort. After all, that doesn’t sound like too much trouble to work out on your own.

The problem, however, is that the responsibility for protecting user data should be on Venmo. From an ethical standpoint, there is no adequate reason for defaulting to unsafe practices and deferring the responsibility to the end user. Unless of course, you care about the data you can gather and not the impact on the daily life, or mindset of the user base. Sure you could easily change your privacy setting, but who has the time for that? How many people really bother? If Dan Salmon’s reacher is to be believed, very few people hit that tiny privacy button, regardless of how easy it is.

On paper, Venmo exists to solve a problem: paying people back, avoiding predatory bank transfer fees, helping people out in a pinch without having to carry cash. And in the process, it has created several new problems that we as users either just have to accept as the way things are, or go out of our way to circumvent as best we can. At this point, I don’t think I can stop using venmo. It’s how I pay my rent, it’s how my friends and I have navigated shared expenses for roughly half a decade. And that’s what scares me. A new technology can just enter into the ether, claiming to solve a problem but creating several more. And yet it’ll entrench itself so deeply, so quickly, into our daily life to the point where we have no choice but to change how we live our lives, rather than questioning the need for the technology in the first place.

Ultimately the price we pay for “convenience,” whatever we may mean by that, is a change in how we think. In particular, how we think about our relationship to the technology around us that we take for granted on a regular basis. And of course, this is by design. Silicon Valley Tech Startups are all about the appearances, the image, the marketability rather than the practicality or even often the profitability.

Uber, for example, another app so aggressively part of our social ethos that its name has become a verb, is roughly $10 billion in debt. We think of Uber, and by extension all ride sharing apps, as the future, as solving a problem, as rapidly breaking down the old and riding into the sunset with a great side hustle, and a sleek black and white logo. But in reality, it doesn’t solve very many problems and it just creates new ones.

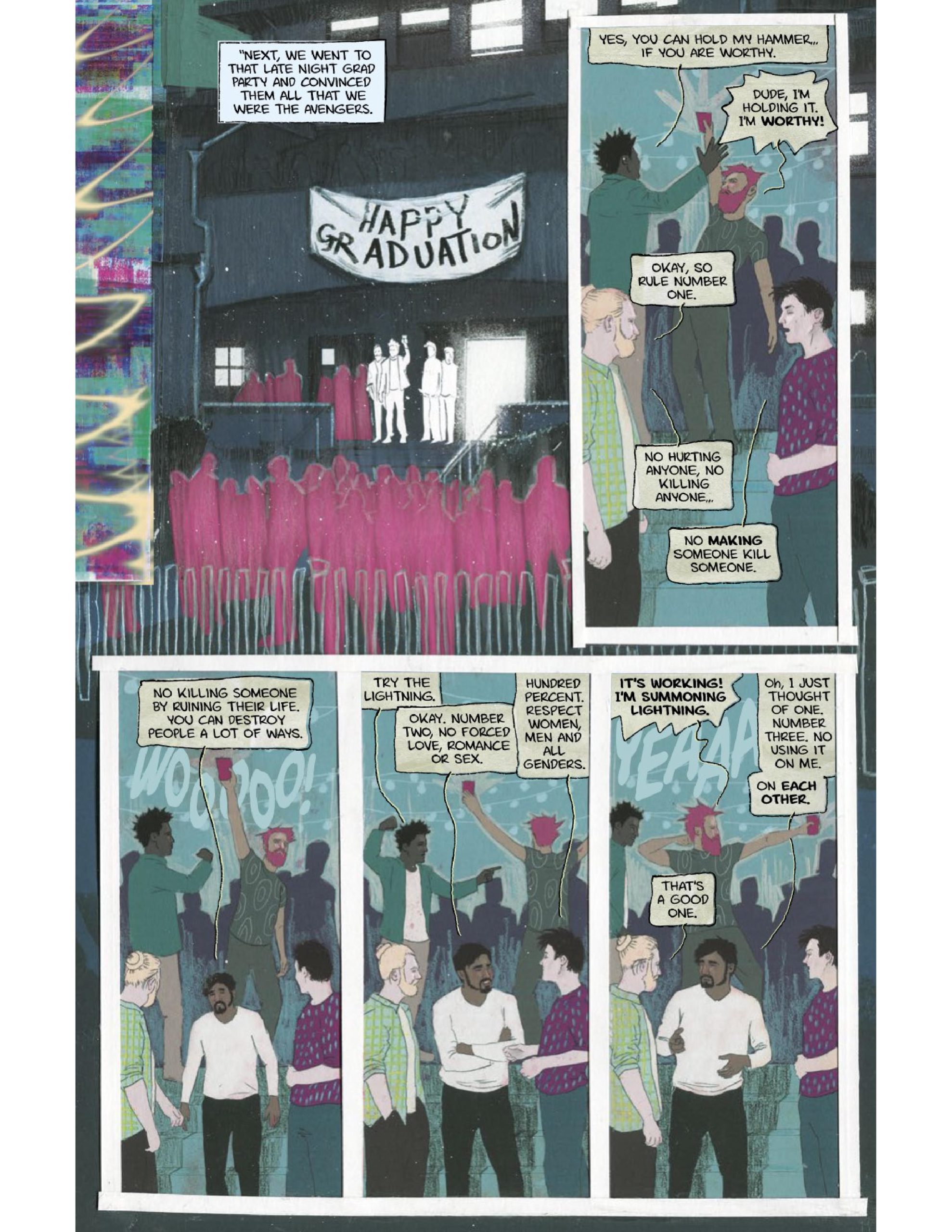

To his credit, Ben and his team in Mindset admit that there are some drawbacks here. After spending a night mind controlling people, they decide they might, potentially, need some ethical guidelines.

If you’re reading this scene and thinking a bunch of drunk, power-mad college students just coming up with a numbered set of basic rules is a bridge too far, then you aren’t familiar with community standards for most social media sites. Dave Willner, who helped create Facebook’s Community Standards over a decade ago, told reporter Jullian York, these standards were the product of “a bunch of twenty-six-year-olds who didn’t know what they were doing” (Silicon Values, p. 140) In fact, despite international use, initially these standards were not even available to read in the languages of all Facebook participating countries, a factor that played into Facebook’s role in the burgeoning burmese genocide, resulting in uninformed content moderation and gradual political instability.

The sad, scary thing about Mindset is that a book about a mind control app that a bunch of uninformed college students abuse which results in manipulation and murder is just about on par with the actual horrors of the tech industry at large. That mind control is less a sci-fi conceit, and more just the basic practices of a tech company hoping to attract a wide userbase and financial investment. There are a considerable number of sci-fi horror stories about technology ruining our lives, but what helps Mindset stand out is that it’s really not exaggerating, it’s laying all the cards on the table and painting not only a bleak picture, but a truly accurate one.

Time will tell where Mindset will go, but for now it’s one of the most compelling and relevant books on the stands.