Tokyo These Days Vol. 1

Tokyo These Days Vol. 1

Creator: Taiyō Matsumoto

Publisher: Viz Media

Review by François Vigneault

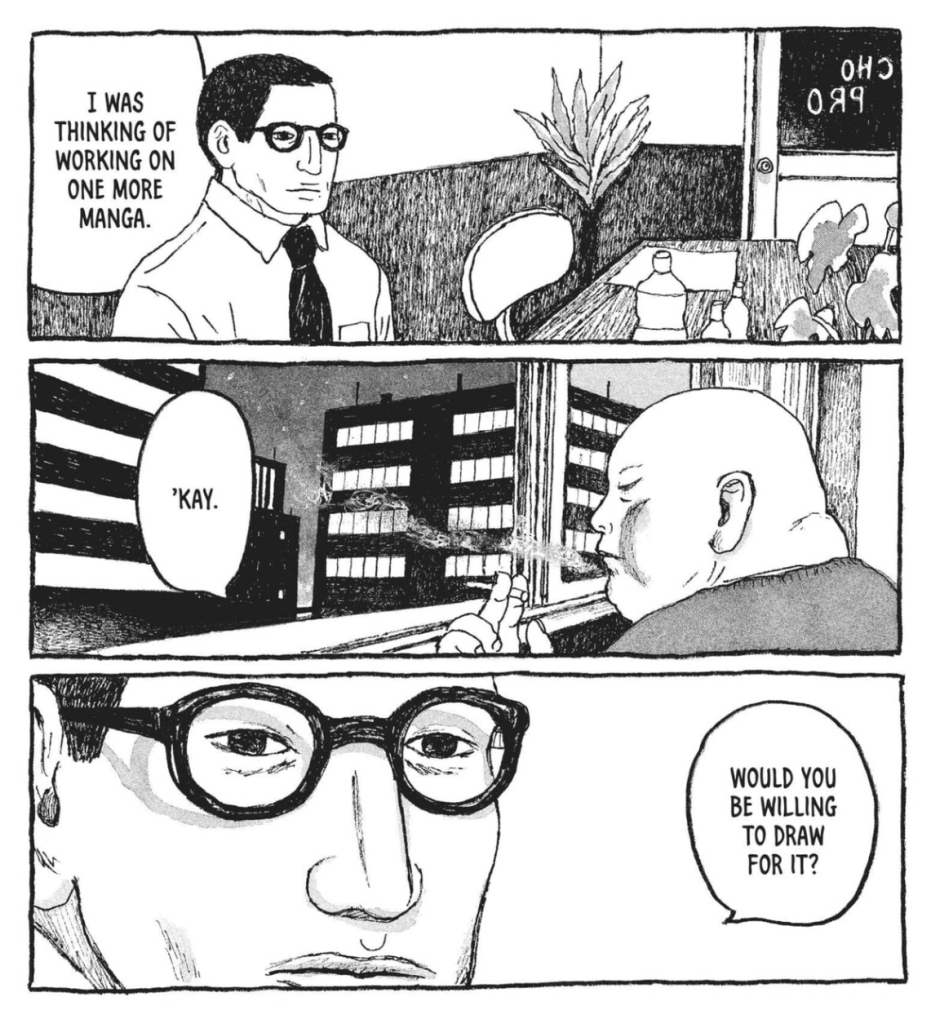

It may come as a surprise that Taiyō Matsumoto’s low-key, quotidian drama Tokyo These Days Vol. 1 (Viz Media) borrows the rhythms and tropes of heist films such as Steven Soderburgh’s Ocean’s Eleven or Christopher Nolan’s Inception: A disciplined yet dishonored professional gathers an unruly band of talented misfits to pull off “one last job” to secure lasting glory and redemption. But rather than a career criminal robbing a trio of casinos or plumbing dreams for industrial secrets, Matsumoto’s unlikely hero is one Kazuo Shiozawa, a soft-spoken veteran manga editor who is living in self-imposed retirement after the magazine under his direction tanked, and the “heist” he is planning is a new manga anthology featuring work from a range of creators both old-school and modern.

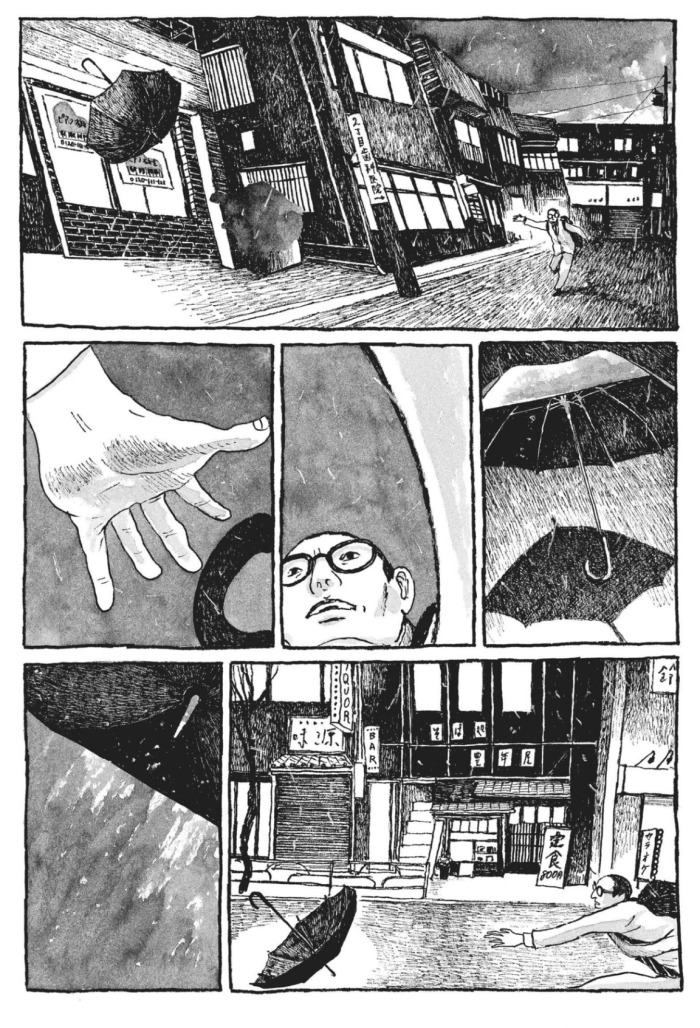

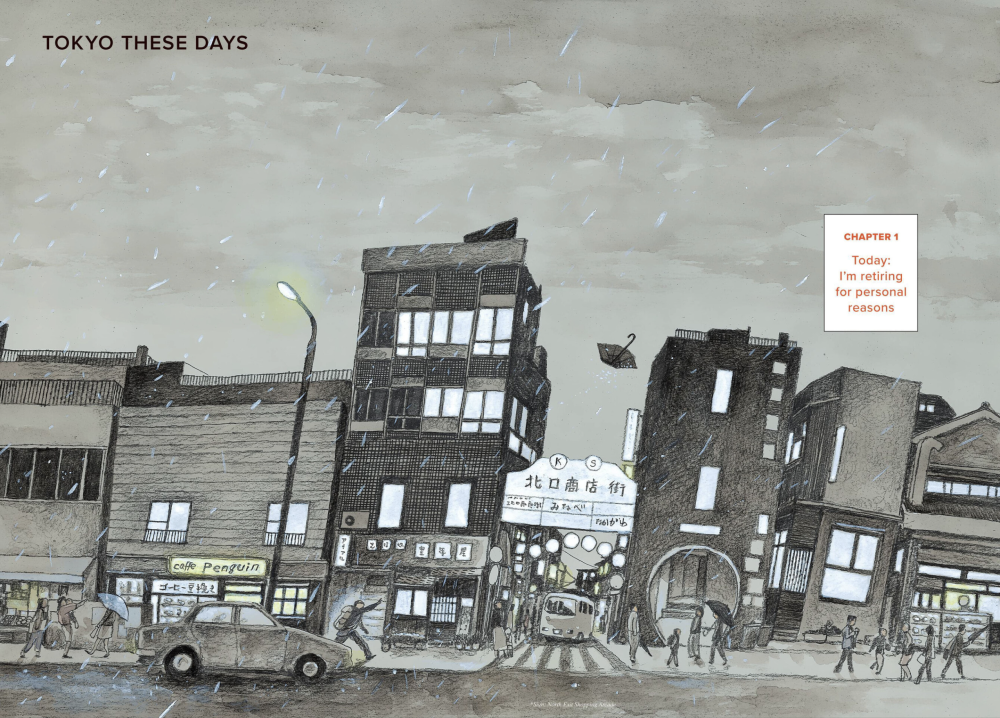

A bespectacled and buttoned-up bachelor, Shiozawa seems to be the picture of decorum and control — all of his office supplies are carefully labeled with his name — but there are hints of a deep-seeded romanticism lurking behind his stoic surface: He sheds a single tear while criticizing a famed mangaka’s recent work (“For the last few years, your work has felt like the life’s gone out of it”), liberally quotes Shakespeare and Goethe, and engages in friendly, extended dialogues with the white songbird he shares his tiny, book-filled apartment with. Even his decision to quit after thirty years on the job speaks to the stringent intensity with which he approaches his metier; when the magazine he edits folds Shiozawa castigates himself mercilessly and shoulders the blame entirely: “I didn’t realize how out of touch I was with the readers. That’s all. I betrayed the trust of all the artists and writers I pulled in. This is the only way to atone” he gravely intones, almost as if he were a modern-day samurai honor-bound to commit seppuku. Like the umbrella that gets swept from his hands by the wind in the opening pages of the book, the “perfection” Shiozawa seeks in manga is the ineffable object that keeps him going, tantalizingly close yet ultimately unattainable (perhaps, with Tokyo’s famed lost and found system and Shiozawa’s penchant for labeling his personal effects, the editor might hope to be reunited with his wayward umbrella in a future volume).

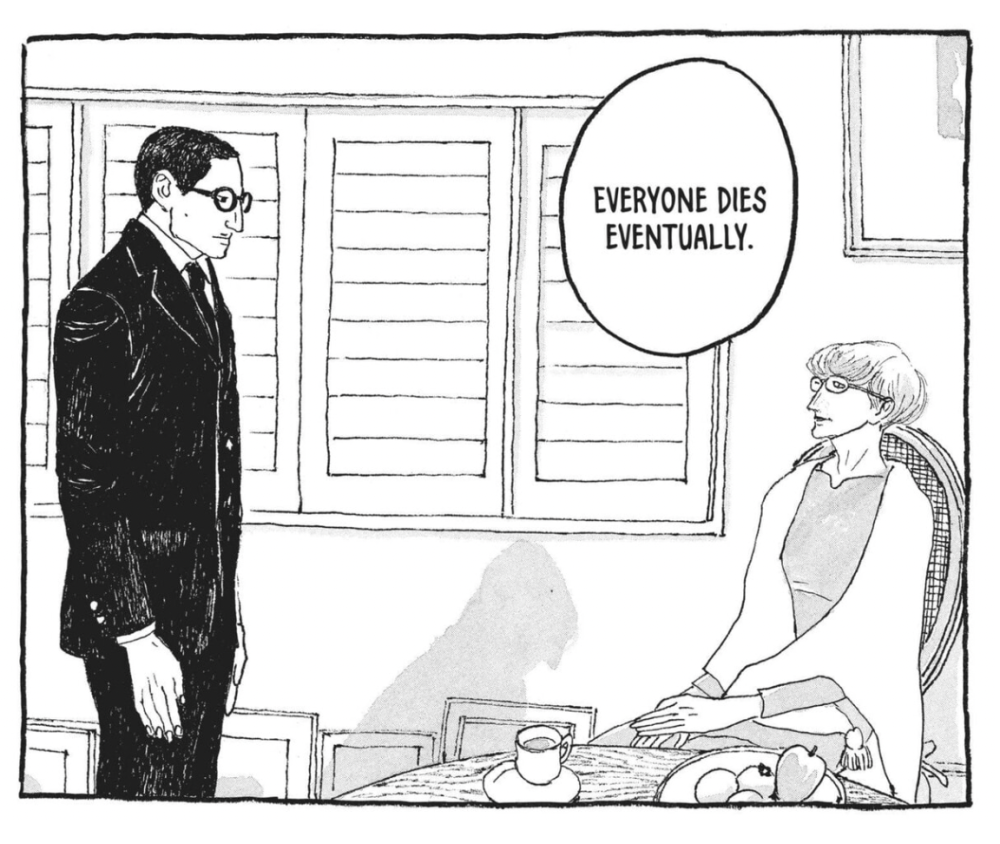

Passion and the search for perfection in the face of a world that doesn’t always appreciate the artistic soul is a throughline in Tokyo These Days. In the studio of Reiko Tachibana, a recently deceased mangaka, Shiozawa is visited by the woman’s friendly, peaceful ghost, and the pair reflect on their working relationship (the reader is left to infer if these two intensely reserved, scrupulously polite individuals secretly longed for something else). Years earlier, a quiet, selfless act by Shiozawa inspired Tachibana to follow her heart and only create the kind of stories that she wanted to. “My sales went down pretty quickly after that” she muses with a wry smile. “Even so, taken in full, I had a happy life. I drew many manga and inhabited many worlds.” As Shiozawa imagines it, her lingering spirit’s one “small regret” is that she never got to do a final project with her erstwhile editor Shiozawa.

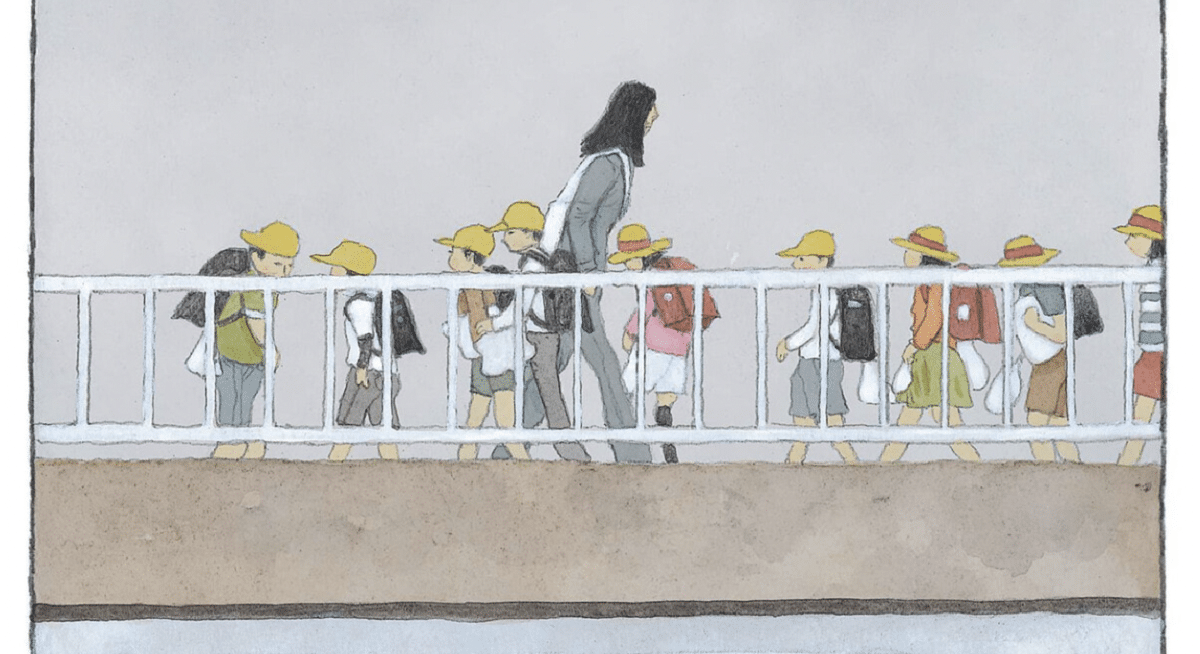

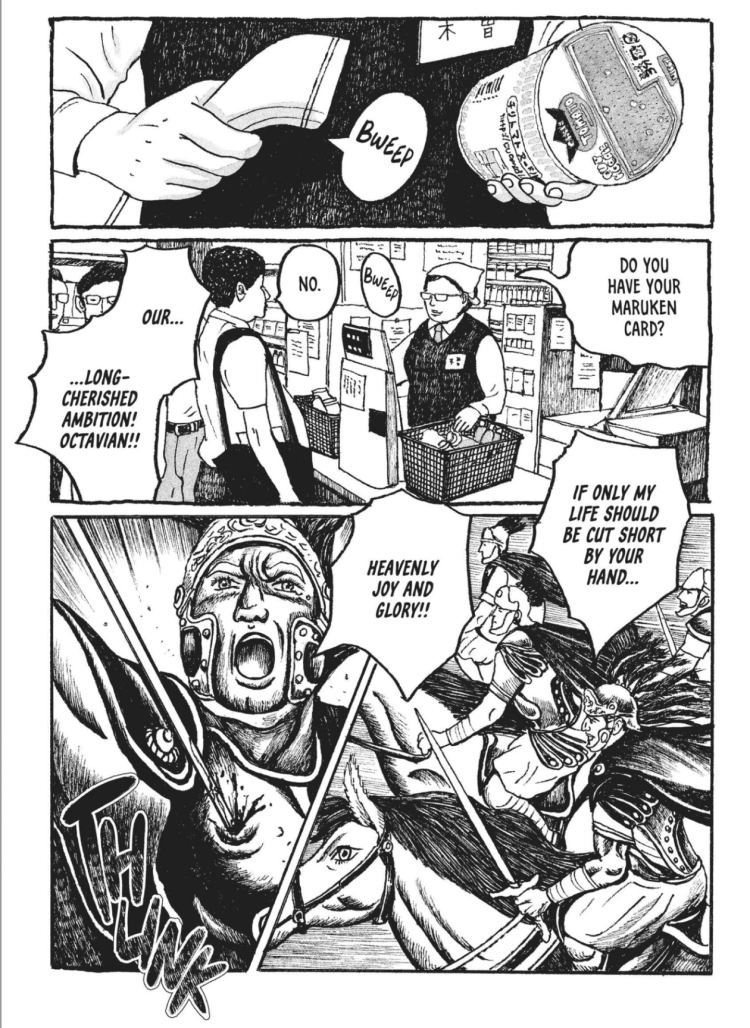

Shiozawa’s quest to put together the “perfect manga” over the course of this series (a second volume of Tokyo These Days arrives in May 2024) may indeed turn out to be futile. The fact that there is no one-to-one correlation between passion for one’s art and success in the marketplace is made manifestly clear throughout Matsumoto’s story. As with any heist narrative worth its salt, the motley crew of manga artists which the mild-mannered editor pulls together have all seen better days. Some are still cranking out work and making a (seemingly comfortable) living in the comics biz: Chosaku, the overweight, hard-drinking, chain-smoking creator of the once-famous baseball manga Uniform Number 15, is working in relative obscurity and patently ignoring dire warnings from his doctor regarding his poor health; the long-haired, cat-loving “bad boy” mangaka Aoki Shu is mired in juvenile conflicts with his new editor Liliko Hayashi. Others have left the world of manga entirely: Shin Arishiyama, a once-venerated mangaka, lives a hermit-like existence as the superintendent of a large apartment complex on the outskirts of the city; Kaoru Kisu, the youngest of the creators Shiozawa approaches and the only woman, works as a cashier at a supermarket when she’s not managing her oddball adolescent son and checked-out videogamer husband. Kisu is the only one of the creators whose work Matsumoto reproduces in this volume; inspired by her encounter with Shiozawa she picks up some pens at an office supply store and starts drawing again at the end of her workday, her story for the anthology is a blood-soaked, larger-than-life Roman epic that is expertly counterposed with the somewhat drab reality of her life ringing up purchases of instant ramen.

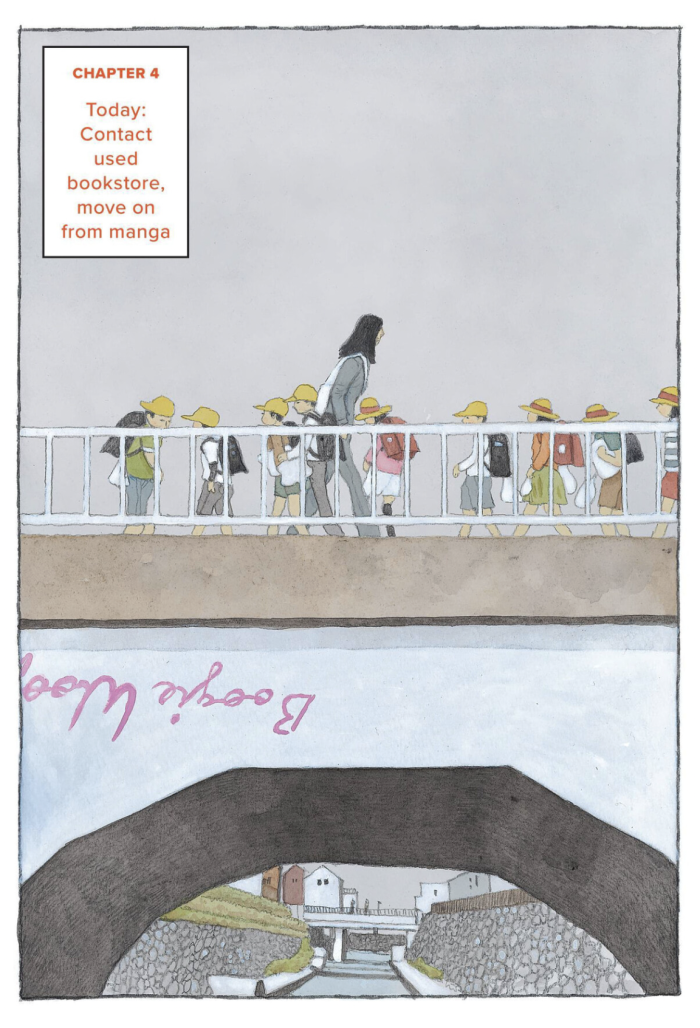

The author of wild sci-fi tale No. 5 (not to mention the sports power fantasy Ping Pong), Matsumoto clearly understands the attractions of escapism—and the unique capacity for manga and comics to scratch that itch—but Tokyo These Days is deeply invested in the subtle pleasures and pains of the quotidian world (the Japanese title, 東京ヒゴロ Tokyo Higoro might also be translated as “Everyday” or “Normal” Tokyo). As in his six-volume series Sunny, here Matsumoto takes a patient approach to his storytelling, little of import seems to happen, and the author lingers on scenes that in another story might have been truncated, or left out completely. Here the routine takes center stage: Each chapter heading has the clipped tone of an entry in Shiozawa’s datebook ( “Today: I’m retiring for personal reasons,” “Ofuna, 11 a.m.: Funeral for Reiko Tachibana Sensei”). A life, Matsumoto seems to underline, is made up of the quiet moments, minor events, and essential errands that fill up our days, one after another.

Matsumoto’s delicate, bande dessinée-influenced artwork, rendered in a mix of scritchy-scratchy linework and soft gray ink wash—occasionally punctuated by sections in pale watercolors—is here particularly grounded in the small details that make up daily living in the metropolis: boxes of dog-eared manga, a pair of black-rimmed eyeglasses repaired with white tape, dip pens and sleeping pills on a tidy drawing table, leaves swaying in the rain. Over and over throughout the book Matsumoto takes the time and space to focus on the streetlights, powerlines, and other detritus of the dense interwoven architecture of the city’s many neighborhoods. These objects and locales serve as more than place setting, they elaborate and deepen the book’s underlying themes of mortality and the quest for the sublime. Matsumoto’s attention to the power of the material world in our daily existence strongly suggests the Japanese literary concept of mono no aware (物の哀れ), which might be roughly translated as “’the pathos of things”; a sensitivity to the transient beauty and melancholic sorrow of the world. The most famous example of mono no aware might be the falling of cherry blossoms in the spring, a sublime scene which only highlights the temporary nature of its beauty, a stunning reminder that nothing lasts.

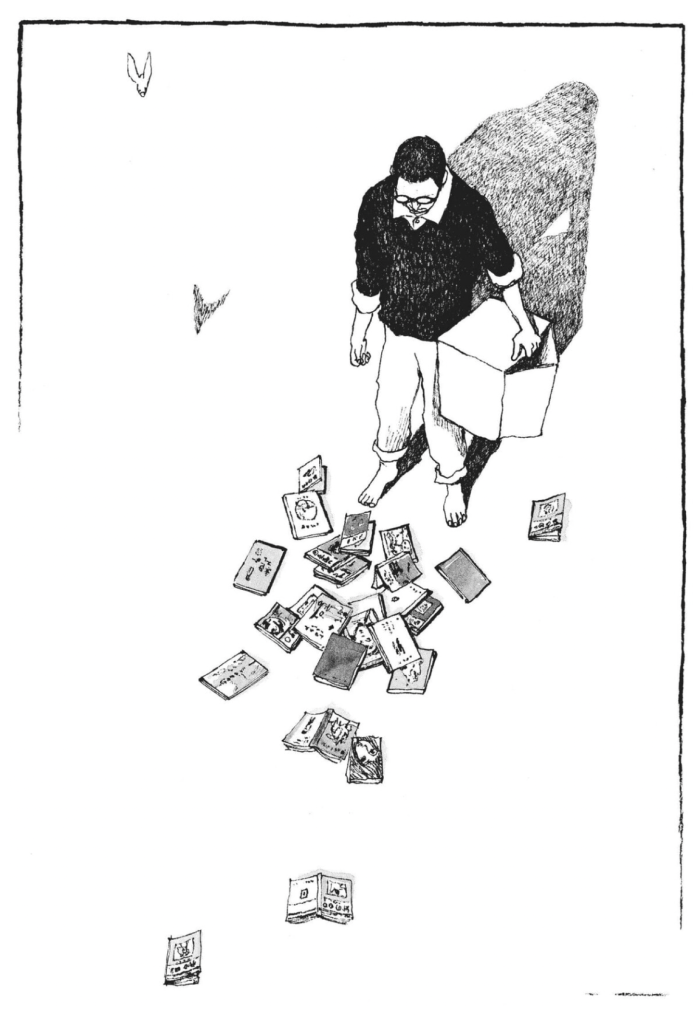

In contrast, the creation of manga might promise a sort of literary immortality: The words and pictures on the page have the potential to far outlive their creators, after all. But it’s clear that Matsumoto has come to understand that nothing, not even a comic book, will last forever. Magazines fold, authors fade into obscurity, and cherished volumes end up being sold on the cheap at a used bookstore. This doesn’t make them less meaningful, however, like human lives, it is precisely the ultimately transitory nature of all our creative efforts that give them weight and meaning. When Shiozawa attempts to cut ties with his past by selling his massive collection of manga, the sight of some of the volumes spilling from a box (including books by Katsuhiro Otomo and Daijiro Morohoshi) ultimately stops him in his tracks. He’s not quite ready to let go of this dream quite yet. The beleaguered bookseller, having spent hours cataloging the books for nought, is understanding: “I get it. I love manga too.”

Tokyo These Days is a slow-paced tale by a master of his craft, and any fan of the medium will find much to love in these pages, from the insider look at the manga industry to the low-key thrills of watching grim professionals pull off “one last job.” Matsumoto’s deliberate pacing and attention to detail just might make you appreciate the little things in life—including a well-worn, beloved book—that much more… But don’t forget that nothing lasts forever.

Read more great writing about comics in The Beat’s Review Section!