by Alex Dueben

Alex Dueben: As anyone who read You’re All Just Jealous of my Jetpack might have guessed, you are a fan of science fiction. What did you love when you were younger? What do you read now?

Tom Gauld: I’ve been reading quite a lot of science fiction recently, a lot of the stuff which I was aware of but had never actually read: William Gibson, Dune, Ian M Banks. I like sci-fi literature but I really love films and comics because the visual side of it was always fascinated me. I’ll watch a really badly written film just to wallow in an invented sci-fi world. Blade Runner, 2001 and Alien all spring to mind as films where the setting is so well imagined and designed that you can really believe in it.

I first fell in love with science fiction when I saw Star Wars as a kid. I was slightly obsessed with it. I watched the films, read the books and comics, had the toys and played it with friends.

Dueben: When you were young, did you want to be a cop on the moon?

Gauld: I never wanted to be a cop, but I think I probably did have idle fantasies about going into space and holidaying on the moon. I’d read dated library books which had a confusing mixture of hard science and utopian science fiction. I remember a book called the Usborne Book of the Future which said that “some experts predict” that there would be a settlement on the moon by 2001 and that the 2020 Olympic games could be held up there. When you’re a child and toy see these ideas set in print and illustrated by an adult, you tend to believe them.

Dueben: What was your initial idea for the book? Where did it begin?

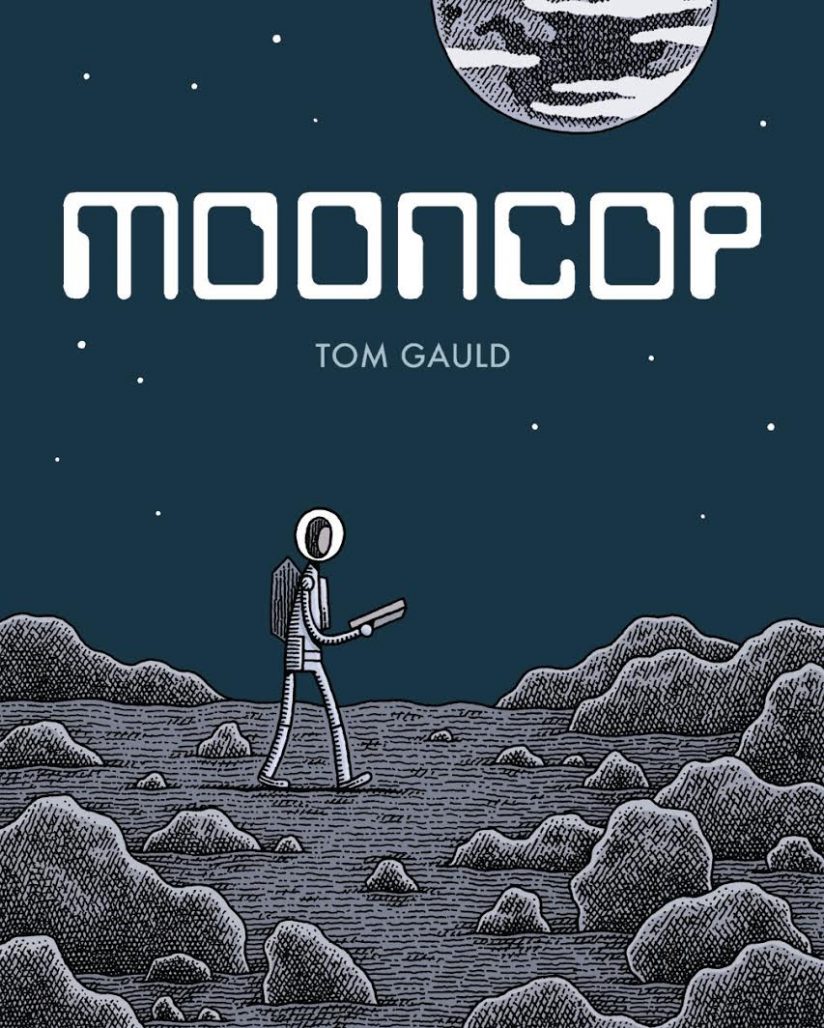

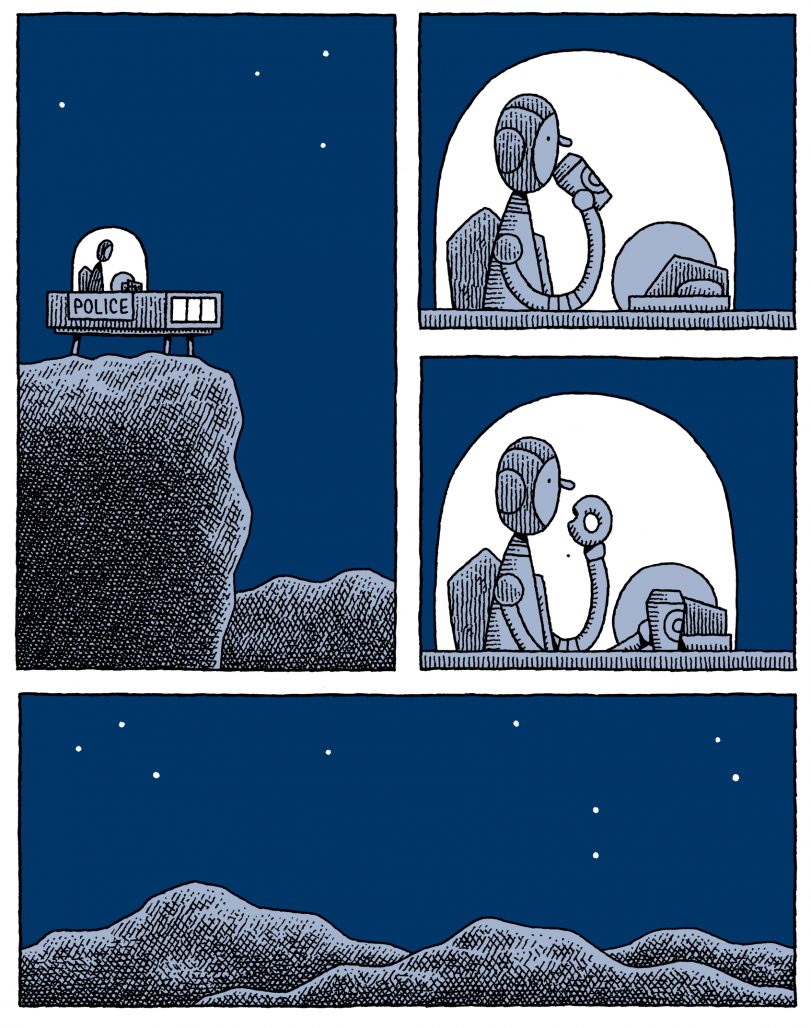

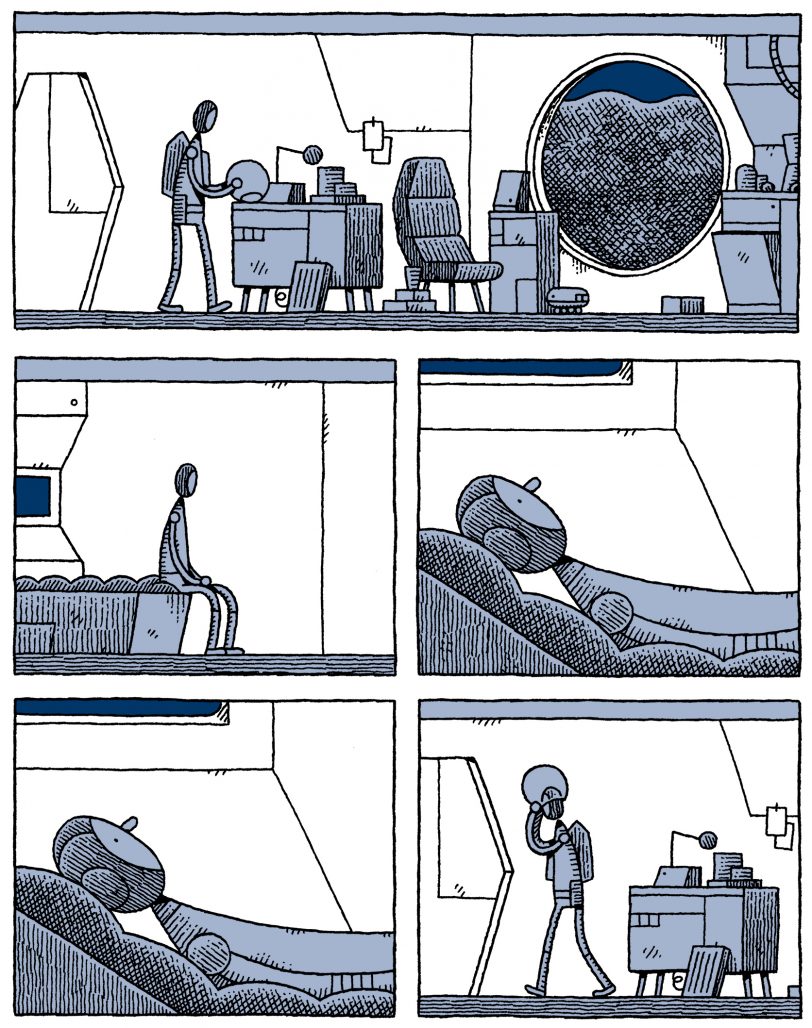

Gauld: The idea of a cop on the moon came from a 1960s tin toy I saw, which was a car with “Space Patrol” on the side and a driver in a glass dome wielding a laser cannon. The packaging showed the car on a deserted moon, with the earth in the black sky above. The toy suggested a future where not only had we colonized the moon, but the enterprise was successful enough that it required a heavily armed police force. The distance between this dated, optimistic idea of the future and the fact that nobody has set foot on the moon since 1972 seemed funny and sort of tragic. I began to imagine the life of a lonely policeman patrolling the moon and the story grew from there.

Dueben: Why the moon?

Gauld: I considered setting the story on another planet instead, but it just didn’t feel right. I think the fact that you can see the moon most nights gives it a familiarity, but we can also take it for granted. I sometimes look up at the moon and think about that short time when men were walking, running, doing experiments and even driving a car around up there.

Dueben: You make weekly comics and lots of short comics features. Do you prefer or find it easier to make short comics? Is that what you prefer as a reader?

Gauld: The short weekly cartoons which I do for the Guardian and New Scientist feel like a more natural fit for me. I find that the constrictions (a theme, a short deadline, a small space) free me up to make something funny or interesting without overthinking or labouring too much.

But then there is only so much that one can do in such small spaces and it’s also interesting to work on a bigger canvas. The longer books and stories are much more of a challenge for me. It’s much harder to come up with an idea that feels worthy of a whole book, then it’s a real battle to shape it into a good story, but that struggle all feels worthwhile when you have a finished graphic novel.

Dueben: Was the episodic nature of the book in part due to the long process and working in between other projects?

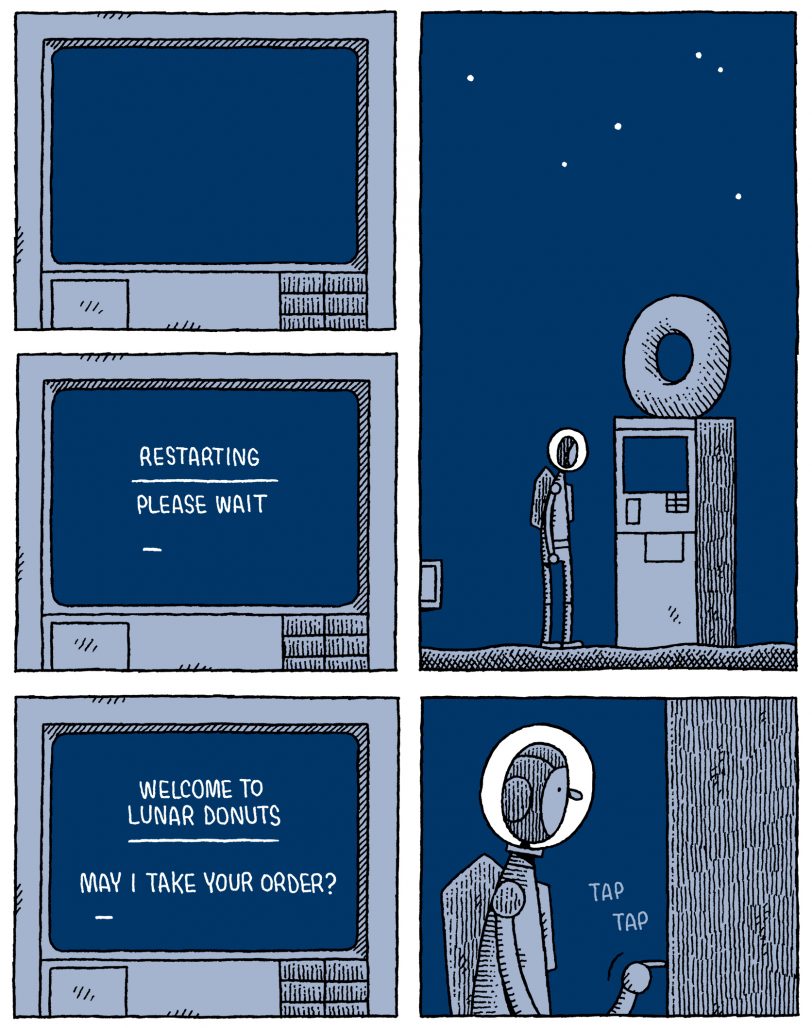

Gauld: Well, it was fitted in amongst whatever else I had to do, so it was created in fits and starts over about three years. But I think the story would probably have the episodic feel however it was created. I wanted the feeling that time was slowly passing and things were getting worse for Mooncop. I thought that having a slightly episodic feel would suggest that other things (or perhaps just the same things repeated) were happening in between.

Dueben: I know you went to art school. Did you go in wanting to make comics or how did you end up as a cartoonist?

Gauld: When I was a young teenager I wanted to draw Judge Dredd or maybe Batman comics for a living but by the time I got to Edinburgh College of Art I’d decided to be an illustrator. I was still interested in comics (I was reading Dan Clowes Eightball and Chris Ware’s Acme Novelty Library which were coming out at the time) but had put aside the idea of drawing them myself. As I was finishing at Edinburgh I realised that all my best work was when I was telling stories with pictures, so I applied to the Royal College of art to do a two year MA course where I mainly concentrated on comics and storytelling. At the RCA I sat next to Simone Lia who was also drawing comics and we self-published some things together and encouraged each other, which led to more self-publishing and then to making comics for magazines, newspapers and proper publishers.

Dueben: I wouldn’t describe any of your work as nostalgic, but you clearly have an interest in the past.

Gauld: Yes, I do. I find history fascinating, and like to imagine how things might have seemed to people, say, five hundred years ago. I like to set my stories in places other than our own world (the past, a sci-fi world, biblical times) because I hope that presenting ordinary things, situations and feelings in an unusual setting can make you see them differently. Also, drawing knights, swords, spaceships and things like that is a lot of fun.

Dueben: What were the science fiction comics you read? Were they British? French?

Gauld: In my teens I read the British weekly science fiction comic 2000 A.D. I loved the crazy, detailed, imaginative worlds that were created in the stories. It was great to come back every week and see a different aspect of Mega City One (Judge Dredd’s hometown). Other than that, and the Star Wars comics I mentioned earlier, I don’t remember reading many sci-fi comics.

The only French comics which made it over to Scotland in my childhood were Asterix and Tintin, which I loved. Apart from a few Moebius comics which somebody showed me later, I don’t think I saw many more French comics till I started traveling to the Angouleme comic festival around 2000 or so.

Dueben: I’m curious what the relationship to science fiction is like in the UK because here in the US we could say, we have a space program and that’s our moon lander and things like that. (And many think we remain the most advanced country in the world, despite everything). On the other hand in London there’s this ultra-modern building next to something a few centuries old, some of the roads and landmarks are the same as they were after the Great Fire. From the outside, it feels like there is a different relationship to time and the past.

Gauld: Yes, that’s all true. I suppose that I take it for granted having lived in the UK all my life. I do like that feeling you sometimes get in a really old building when just for a moment you think about all the people who have been there over hundreds of years. I suppose a bit like Richard McGuire’s book Here.

I imagined the colony in Mooncop as a very international affair, not just a NASA operation, like an attempt to make a Star Trek-like utopia which unfortunately doesn’t quite work.

Dueben: To what degree is Mooncop about this relationship to science fiction more than anything? This idea of the 21st century that was presented to us.

Gauld: It is very much about that. I looked at some NASA imagery (particularly the excellent book Full Moon) and thought a bit about real space science, but I was much more interested in the sci-fi ‘idea’ of the future and living on the moon. Like the world presented in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 which never actually came true, but feels completely believable.

Dueben: I have to ask, why is the dog in a bubble as opposed to having a helmet attached to a collar?

Gauld: I was looking at various space suit designs for the characters such as those for Kubrick’s 2001 and Herge’s Tintin moon books as well as the suits of real astronauts. There were various dog suits made by the Russians and also Snowy’s suit from Tintin, but they didn’t look right when I drew them. I thought they were anthropomorphising the dog too much, so I tried to think of another way he could be out and about on the moon. When I thought of the hamster ball idea I was very happy because it just seemed quite funny to me.

Articles like this are why I still visit The Beat.

Comments are closed.