Genres have their own musical inclinations. There are just some sounds that feel at home in certain storytelling worlds. Horror, for instance, resorts to pianos and violins to either generate terror with the slow and ominous sounds these instruments are capable of or to set up a jump scare with sudden and forceful notes. Romance uses whole orchestras to generate a sense of wonder when lovers fall in love at first sight. Noirs rely on the melancholy sounds of muted trumpets and French horns for their descents into broken morals and bloody murder.

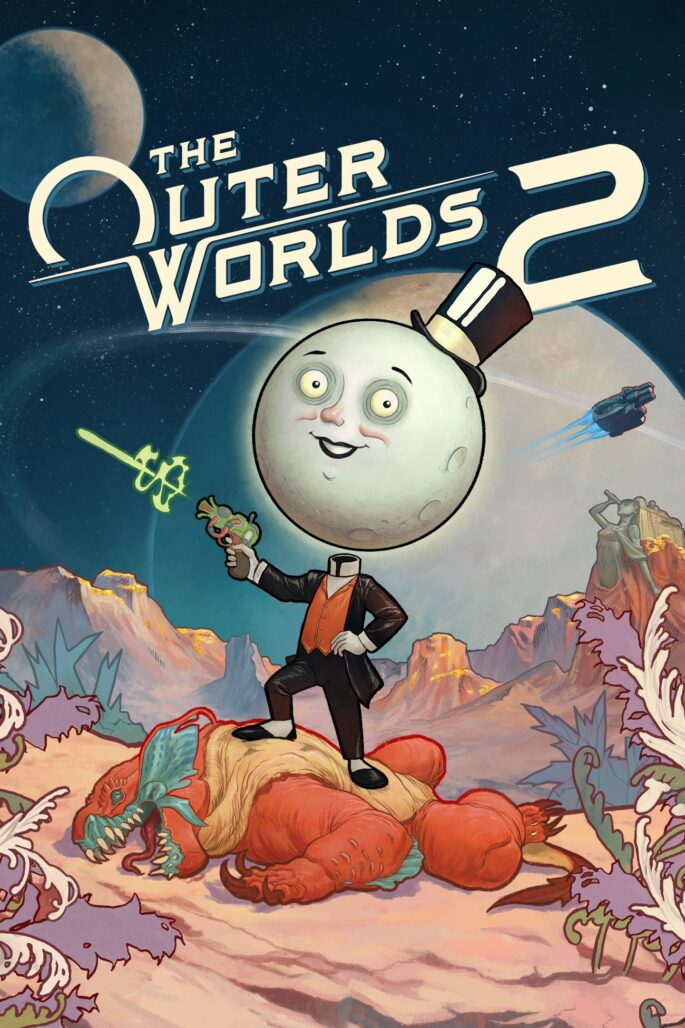

Science fiction, though, has perhaps one of the most sweeping soundscapes in fiction. It has to account for discovery, wonder, fear, existential dread, cosmic spectacle, introspection, adventure, and hope. It’s an eclectic selection of sensations and emotions that Obsidian’s The Outer Worlds 2 composer Oleksa Lozowchuk (alongside Antonio Gradanti) is quite aware of, and he goes through each one in the process of creating the music that’ll accompany gamers and help them craft a narrative shaped by their in-game decisions.

Lozowchuk is the co-founder of Interleave (along with Christian Hurst), a collective of music and audiovisual professionals that partner with clients to help expand their creative visions via sound design. They’ve worked on triple-A games such as Horizon: Forbidden West, Borderlands 4, and Death Stranding 2: On The Beach.

The Beat sat down with Lozowchuk to discuss the challenges of crafting a score for a game that is based on player choice and what’s in store for the future of music direction and sound design.

RICARDO SERRANO: The Outer Worlds 2, like the previous game, is an RPG that hinges on player choice. Experiences will vary wildly from player to player. How did you approach this dynamic to create a score that would fit the multiple directions players could take?

OLEKSA LOZOWCHUK: I was the music and audio director at Capcom for about 10 years, and I got to work on the open world Dead Rising series. So, I had already encountered the challenges of player choice before. I was kind of aware of the levers that you have to push and pull to make things work.

One interesting idea that changed our approach to music, though, was the inclusion of radio stations in the game. Brandon Adler, the game’s director, wanted three radio stations that represented the three very different factions in the story. They needed to have their own vibes, their own aesthetic. They’re supposed to help expand on the player choice aspect. What you choose to listen to in a specific area, and how often, will help you create your own narrative path within the game.

In addition to that, there was the main thematic music that we wanted to have for the big beats in the story, the ones that you’ll eventually listen to regardless of choice. We had discussions on whether to inject more melancholy in parts so it’s not just satirical comedy, for instance.

I like to see this as adding more ingredients to the experience, all of which influence where you choose to go in the game and how you choose to play in certain areas. That said, we were careful not to fill spaces with too many notes. We wanted the right amount so that players could close their eyes and know where they were in the world at a given time. We built up tracks where we would have a base layer that was unique to that world, tied to a unique instrument or unique characteristic. Then, we would stack and build things up so they would fit well whether you were playing stealthily or in any other style of gameplay you were experimenting with. The music would adapt to your actions, adding an important layer of interactivity to the score.

SERRANO: Sci-Fi soundtracks have a particular feel, prioritizing certain sounds to evoke that sense of exploration and discovery associated with genre. Did you feel a bit inclined to try and capture some of those classic sounds or did that not figure into your thought process?

LOZOWCHUK: We definitely had an esthetic that we were going for with the exploration music. I mean, it is a sci-fi kind of fantastical exploration experience we had here, so you can’t veer too far from some of the core themes of the genre. What was important was to ground the emotions, either for each planet or for each faction as you encounter them. That usually entailed either creating an instrument for an area or finding the right sound or the right combination of sounds for it.

We aimed at creating something that represented peoples and places. We would only use certain instruments for certain factions and not repeat them to create clear distinctions. For me, it was more like being a chef. If you’re directing, or if you’re composing, your job is to find the right balance for multiple things at once. Some areas of the game need some salt, some areas need extra spice, some need added sweetness, and some just need to be savory. It’s all about finding the right balance.

SERRANO: Your audio production company Interleave helped create the audible universe of the game along with Obsidian’s sound designers. This entails heavy investment in the storytelling component of the game. How much freedom to add to the script did you find in the process and what do you think your team added to the game in that regard?

LOZOWCHUK: Obsidian is super collaborative. They have a very clear vision of what they want to do, but they want to be true partners as well. Interleave was brought in shortly after Outer Worlds 1. We were essentially there to help them start rebuilding the technical audio infrastructure for the sequel. So, we came in to help their internal team shape the sound design.

They liked the work we did, so they then approached us to explore the idea of scoring the game. It was an organic partnership with them. What was cool about it was, all throughout that time, they were very open to allowing us to pitch whatever would help them tell the best story.

We had very productive creative sessions, and they weren’t all winners. But they would let us know what worked and what didn’t. When we agreed on an awesome idea, though, we really went deep into the process of making it happen. We collaborated a lot on the songwriting, especially in terms of how they’d represent each faction and the ideals they lived by. We looked for the stuff that cut through and got everyone humming or acknowledging the catchiness of the song. We were very much in sync with what worked and what didn’t.

SERRANO: What’s in store for the future of this sound space? What will you able to do going forward that you couldn’t do previously?

LOZOWCHUK: Choice. It is everywhere now. There’s almost too much choice. I don’t know about you, but there’s so much noise and signal. And you don’t know what’s signal and what’s just a barrage of noise. I almost feel like, going forward, people are going to lean more on taste makers, the same way we kind of lean on chefs or sommeliers for food and wine.

It’s not that I have the same palette as another person and so strive to be authority on taste. It’s better to think about it in terms of people that have been able to get rid of all the noise that’s not important and pare it down to a more interesting selection of experiences. It’s better to sift through five choices rather than five hundred.

I really do feel like that role is going to be very important going forward, because it’s almost like pre-digesting or curating something that feels right. People only have so much time and bandwidth, and when they experience something—whether it’s listening to a piece of music, playing a game, or watching a show—they want it to be authentic. They want it to be organic. They want to know they’re not wasting their time.

We’ll have more complicated systems and more interactivity, and we’ll tell cooler and crazier stories. That’s all great, and that’s kind of a given. But I think the actual role of artists is going to be more about connecting us to our humanity so that we can get back to the days of amazing art. We don’t want generic or forgettable anymore. We want artists with a deeper understanding of the role that we play in affecting and shaping the soundtrack of people’s lives.