In Flash Forward: An Illustrated Guide to Possible (And Not So Possible) Tomorrows by Rose Eveleth, available TODAY, April 20th, 2021, you can get a glimpse of what might be in store for humanity around the next corner. Based on the Flash Forward podcast, hosted by Eveleth, this collection alternates between comics that dramatize futuristic possibilities and Eveleth’s nonfiction prose chapters, which combine historical anecdotes and professional testimony to deliver fascinating meditations about the world of tomorrow!

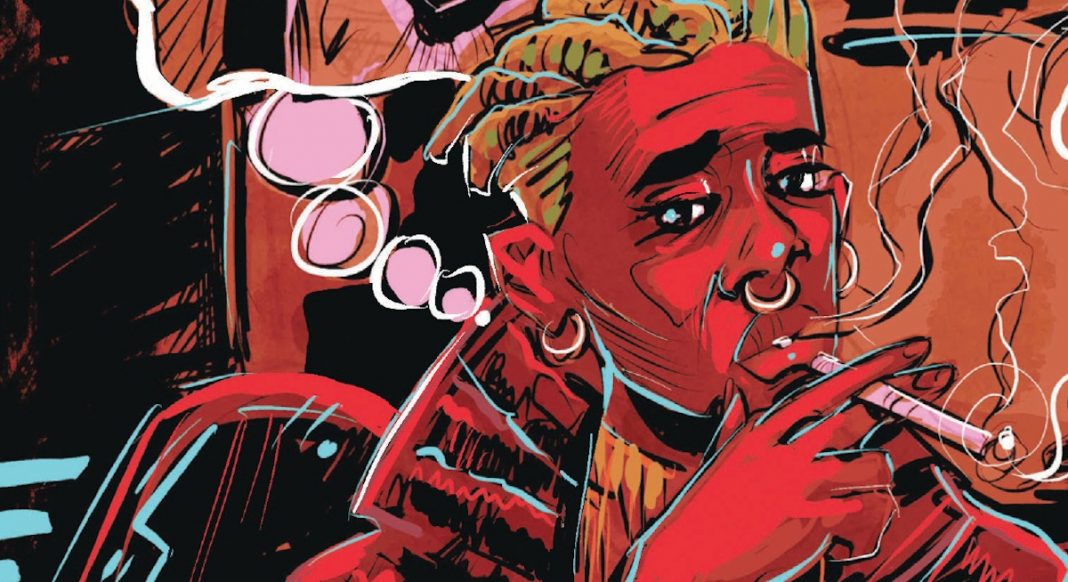

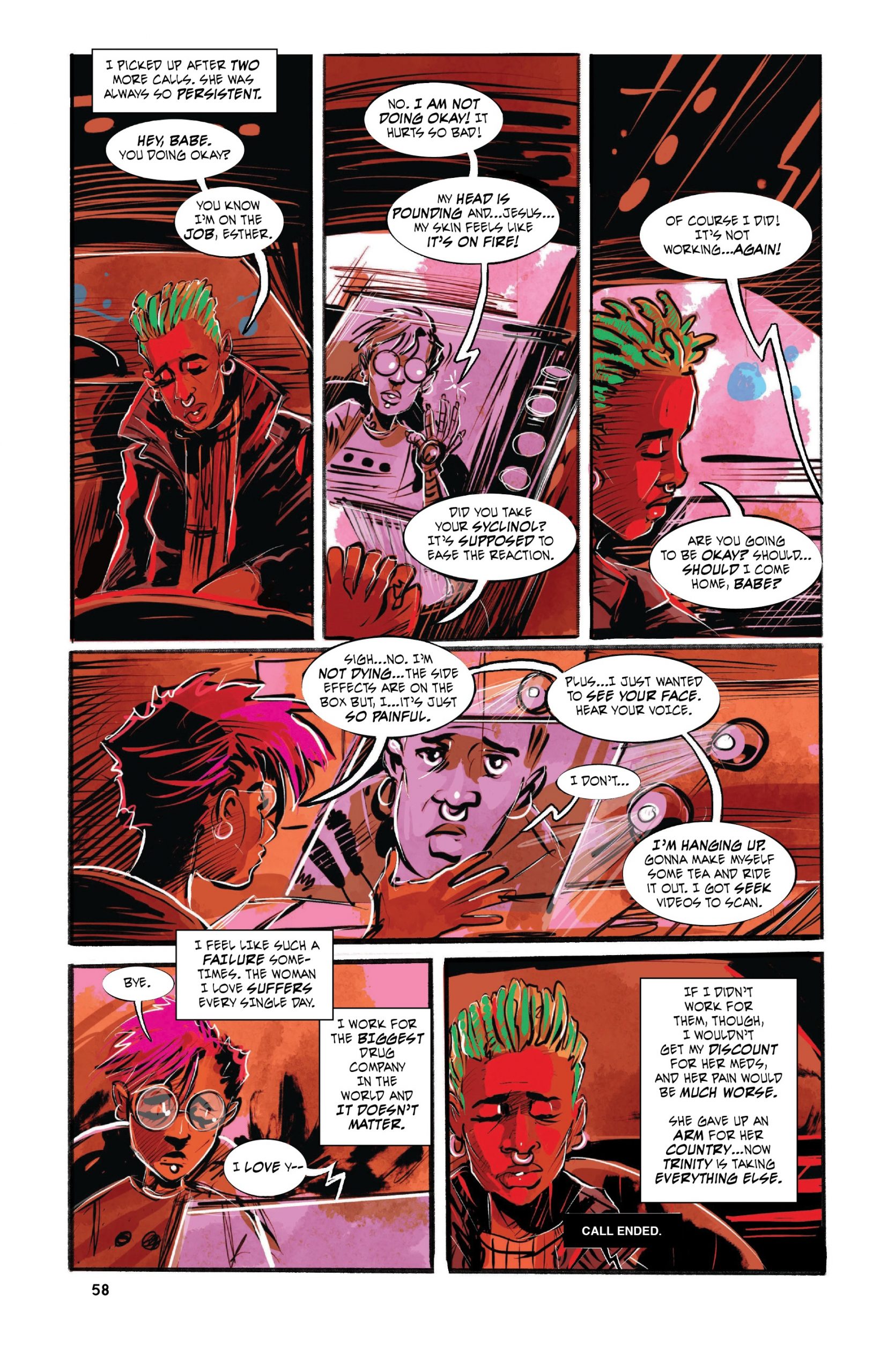

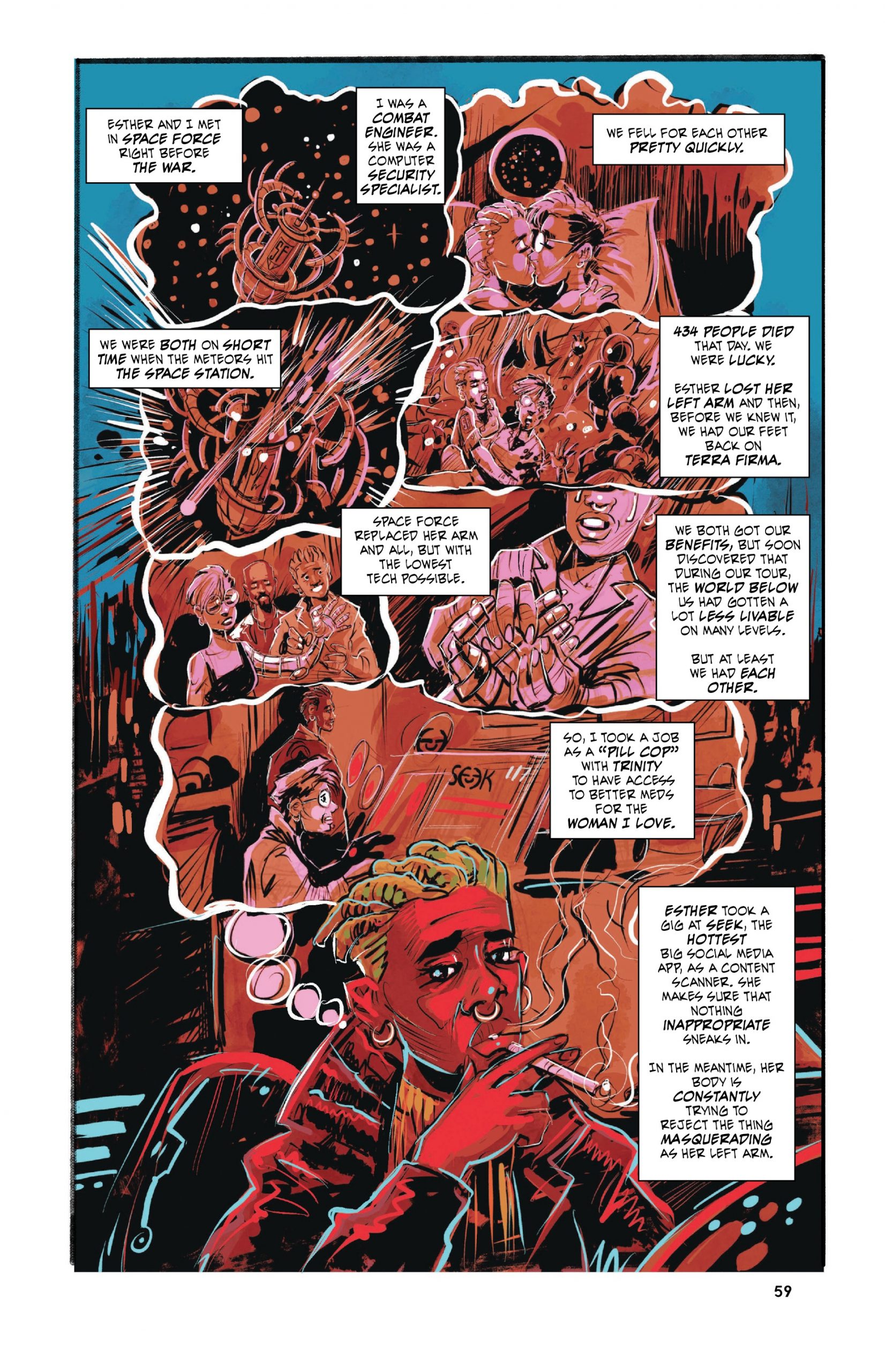

The hybrid anthology includes 12 comic stories of our (possible) future(s), from creators Amelia Onorato, Ben Passmore, Blue Delliquanti, Box Brown, Chris Jones, John Jennings, Julia Gfrörer, Kate Sheridan, Maki Naro, Matt Lubchansky, Sophia Foster-Dimino, Sophie Goldstein, Zach Weinersmith, and Ziyed Ayoub.

The Beat caught up with Eveleth over email to find out more about what speculative fiction inspired her, why comics are such an ideal medium for exploring possible futures, and what they thought about writing a sometimes-hopeful book in the sometimes-unhopeful year of 2020!

AVERY KAPLAN: Can you tell us about the process of how this book came together, and how it relates to your podcast of the same name?

ROSE EVELETH: Once a podcast crosses some invisible threshold of popularity, there’s always a push to take it to a new platform — whether that’s a book or a TV show or even a movie adaptation. So when Flash Forward took off, I was pretty quickly approached by book editors and agents about some kind of book adaptation. It was very flattering! But if I’m being honest, I also couldn’t envision it. I didn’t want to just repackage the same content from the show into book form — that sounded boring to me. And I couldn’t really picture how to make the book fresh and new either. Then Sophie Goldstein emailed me, proposing a comic anthology collection. And as soon as she described that I knew that was the right way to go. So truly all credit for the conception of this book’s format goes to Sophie! I feel incredibly lucky that she reached out and then was able to work on the book with me and Matt Lubchansky.

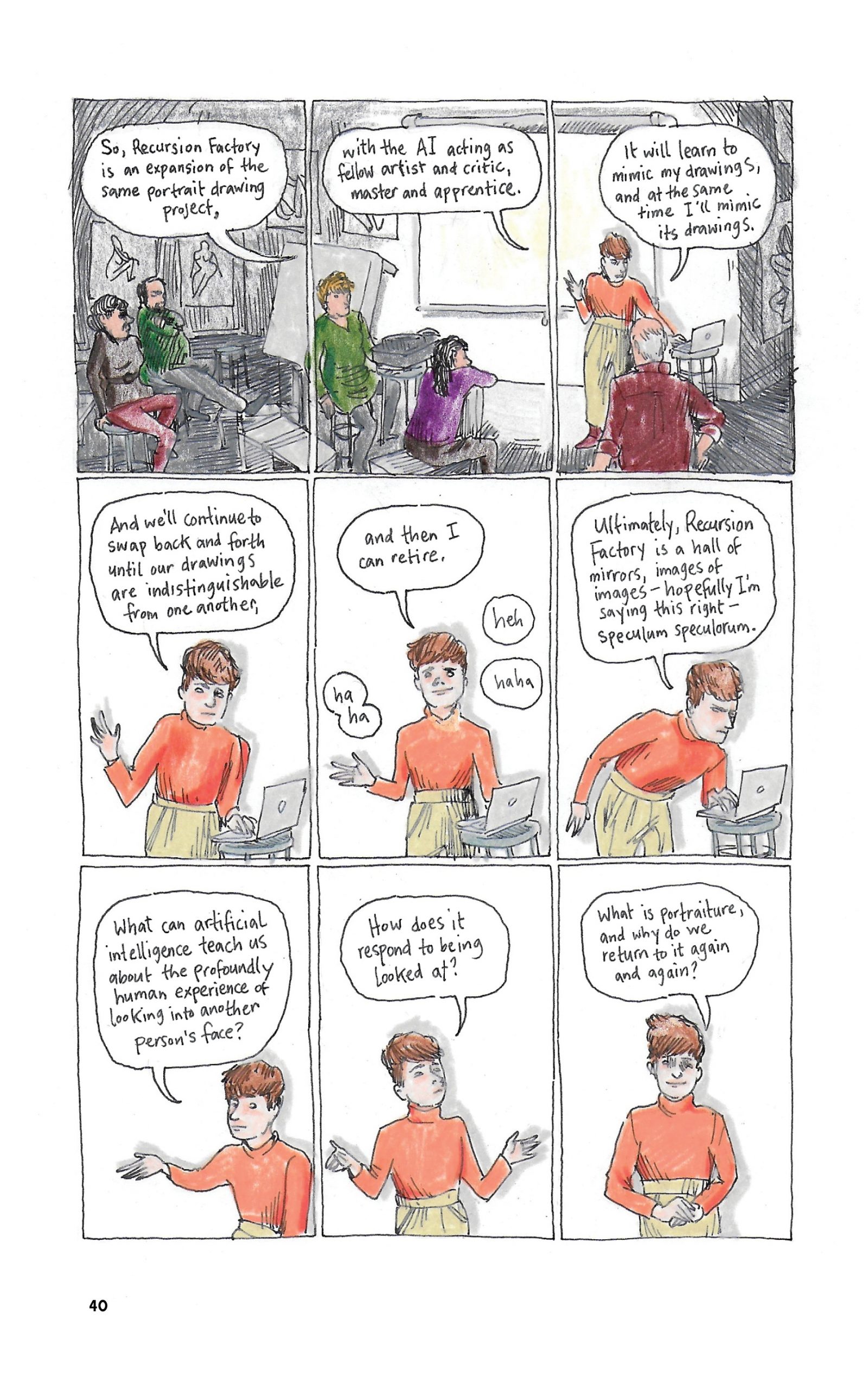

Each chapter of the book is formatted much like an episode of the podcast: we take a trip to the future, using a fictional storyline, and then we discuss the reality of those ideas. Matt and Sophie helped me bring in some incredibly talented artists to bring the fictional futures to life, and I took on the task of doing those comics justice with the essays that follow them. The comic artists were presented with the full list of Flash Forward episodes (there are over 100 by now!) and picked the three that were most exciting to them. Then Matt, Sophie and I worked with them to figure out the story we wanted to tell. My goal was to really let the artists envision the futures that they were most interested in, while also keeping the book grounded in the Flash Forward ethos. It was such a rewarding process and I learned so much from all the artists in putting it together! They came up with characters and storylines and ideas that I would never have on my own.

KAPLAN: Was there any topic that was especially challenging to research or find information on? Did your research lead you down any unexpected paths?

EVELETH: Every chapter had its own unique challenges — the fun and weird thing about the future is that you are always trying to figure out what is going to stay relevant and what might feel dated in a year, or five, or ten. The Piraceuticals chapter (which John Jenning’s created an amazing comic for) was a challenge, for example, because anything about drugs and drug production written during 2020 was going to be a bit of a tricky thing to do (the book was completed long before a COVID vaccine had been developed). The fake news chapter (which was brought to life by Zach Weinersmith and Chris Jones) was hard because that technology is moving so quickly that by the time the book came out, every example I might give would likely feel dated.

KAPLAN: Were there any elements of the future that were especially difficult for you to approach (like for me, the idea of being separated from my pets is hard to contemplate)? Alternatively, does any specific concept make you especially hopeful for what’s in store?

EVELETH: It’s hard for me to imagine being separated from my pet too! Maybe this says something about me, but I’m actually most drawn to ideas that I find really hard to imagine sometimes. Because it really pushes me to reconsider the world, and how we got to this place, and whether it’s the right way or if maybe we could do something else. Often big cultural shifts are harder to imagine than technological ones — it’s sometimes easier to imagine flying cars than a big shift in how we think about gender, for example. But changing our conception of gender feels so much more important and rewarding and exciting! (Of course, technology and culture aren’t separate, they’re one and the same, and influence each other directly, but you know what I mean hopefully.)

KAPLAN: In order to look to the future, you frequently draw on the past! Did you have a particular historical antidote that stands out to you as a favorite? Is it just as important to think about the past as the future when we are thinking about what’s next?

EVELETH: Yes! I’m a big believer in history being the most overlooked part of the future. And not simply so that we don’t repeat the same mistakes over and over again, but also because it is the only way to really understand how and why things work today. You can’t actually understand why facial recognition systems regularly fail to “see” faces of color without looking at the history of these systems. Lots of amazing scholars have written about the ways that technologies have come directly out of policies meant to control Black folks in the United States, and how race is itself a type of technology (I’m thinking of Dr. Simone Browne and Dr. Ruha Benjamin who’ve done amazing work on these ideas).

One of my favorite little historical anecdotes from the book is about a 1982 predecessor to today’s “deepfakes.” I think a lot of people have this idea that now, all of a sudden, now that there is a certain kind of technology that can generate convincing fake images and videos, that we’re entering a whole new world of misinformation. But in 1982, a punk band named Crass released a tape that took clips of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, and made it sound like they had planned to sacrifice a British boat in order to escalate the Falklands war. Long before photoshop or algorithmic video generation, people have been trying to sew chaos using fake media. Today that media can spread far faster and more broadly, and I’m not arguing that it’s not a problem. But knowing more about the ways media has been manipulated in the past can help us understand not only how to guard ourselves against being fooled, but also which pieces are actually new, and which parts of the process we should pay most attention to.

KAPLAN: Judging from the introduction (and some other notes), you completed work on this book around this time last year – and for residents of the United States, the spring of 2020 was an exceptionally uncertain time. How are you feeling about the future a year later? Has your perspective shifted from where you were this time last year?

EVELETH: It’s always weird making anything about the future, since the future just keeps happening, but it’s especially weird making a book about the future. Even in “normal” times. Publishing is slow, and it’s usually about a year between when you finish a book, and when it’s out in the world. Then add on top of that the year we just had, and yeah, it was stressful. I don’t tend to worry too much about “getting it right” when it comes to the future. Flash Forward isn’t about predictions, it’s about possibilities. But when so much in in flux, it makes even thinking about what could happen next harder.

But the thing about the pandemic is that while the virus itself was novel, a lot of the problems that made 2020 so bad for so many people in the United States and beyond aren’t new. Income inequality, racism, the gutting of the social safety net, the rise of conspiracy-theory-as-political-ideology, none of these things are new. Billionaires got richer than ever during the pandemic thanks to systems and incentives that were in place long before the first COVID case. What the pandemic revealed, I hope, was how all of these can make a bad situation dire, and how important it is to rethink the future. So in many ways, my thinking and perspective hasn’t shifted that much (not to mention I did an episode about a pandemic four years ago on Flash Forward, so I had already thought about this future a fair amount). My hope is that the pandemic has made a lot more people realize that the systems we have set up now don’t work, and should be changed.

KAPLAN: Can you speak to why comics are such an ideal medium for engaging people in conversations about the future?

EVELETH: One of the challenges of making any kind of work about the future, particularly work that’s fundamentally grounded in journalism & reporting, is that it hasn’t happened yet. You can’t go off and interview someone who has had these experiences, because they don’t exist yet. That’s why I combine fiction and journalism on the podcast, to give people something to imagine, a situation for them to step into and think “huh, what would I do in that situation.” Comics offer an added visual layer on top of that, compared to what I can do with the podcast. The artists in the book were able to bring these worlds to life in a really beautiful and compelling way, to show people what these futures could look like. I’m not a comics expert by any means, but I love that they offer this interesting middle ground between something totally animated, and something purely described in text. They give you some of the images, but allow for a lot of your own imagination between the panels, for the reader to inject their own point of view too.

KAPLAN: Has there been any sci-fi or speculative fiction story (in any medium) that has been especially inspirational for you when considering the future for Flash Forward?

EVELETH: Oh wow so many, it’s really hard to pick just one! I really admire Annalee Newtitz’s book The Future of Another Timeline, which has a lot of really big cool ideas about the future, the past, and who gets to shape history.

KAPLAN: Is there anything else you’d like me to include?

EVELETH: I’m incredibly thankful to all the artists who created comics for this book. The book would be nothing without them, and they each brought such amazing insight and energy into their pieces.

Flash Forward: An Illustrated Guide to Possible (and Not So Possible) Tomorrows is available at your local bookstore and public library beginning today.