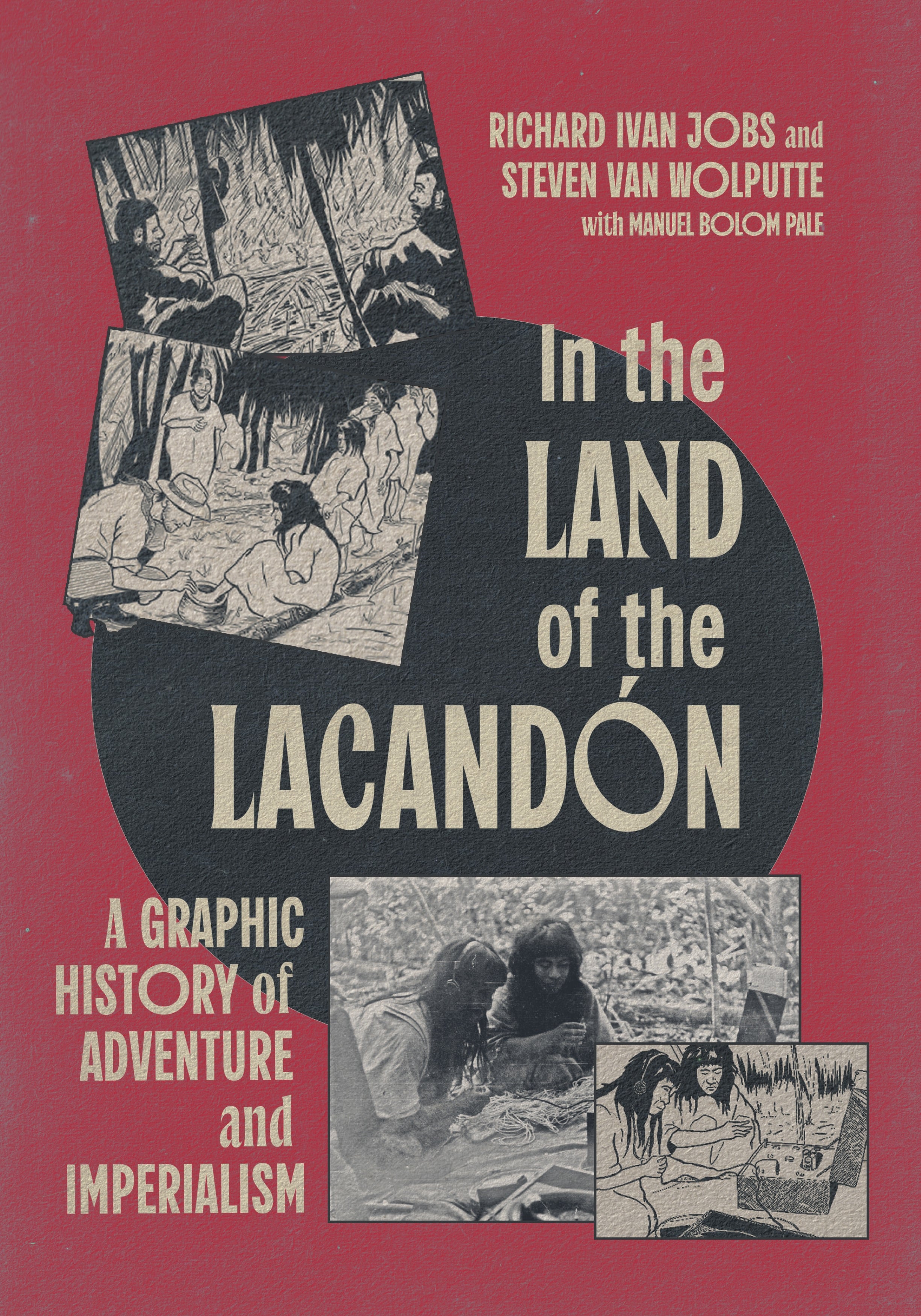

McGill-Queen’s University Press released In the Land of the Lacandón: A Graphic History of Adventure and Imperialism, written by Richard Ivan Jobs and illustrated by Steven Van Wolputte, earlier this month.

In the Land of the Lacandón follows Bernard de Colmont, a French ethnographer and amateur filmmaker who ventured into Chiapas in the mid-1930s to study the Lacandón people and broadcast their way of life to a curious European public. The Lacandón, considered a “lost tribe,” were considered the closest living relatives of the ancient Maya. While de Colmont’s adventures generated a lot of attention, the Lacandón were silenced in his tale.

A century later, Richard Ivan Jobs and Steven Van Wolputte created a graphic history based on de Colmont’s narratives and images. This is presented alongside an essay contextualizing the tale and an evocative, reflective poem by Tsotsil writer Manuel Bolom Pale, offering an Indigenous perspective on the encounter.

The Beat talked to Richard Ivan Jobs about In the Land of the Lacandón, how stories of the colonial-imperialist hero appear in media today, and the history of exploration, science, and media.

OLLIE KAPLAN: In the “Preface,” it’s stated that a graphic history format was chosen because it allowed the team to create “a single comprehensive narrative” out of “a mash-up of various scattered and incomplete original sources. Can you elaborate on why you wanted to tell this story as a graphic history?

RICHARD IVAN JOBS: We had dozens of original photographs and a documentary film to use as visual sources. Moreover, we had radio lecture transcripts and magazine articles authored by Bernard de Colmont himself. Thus, rather unusually for a graphic history, we did not have to rely on inventing images or fictive narration to tell the story, but could draw directly from primary historical sources. As for the story itself, the first time I came across it, without having done any of the research, I saw it as an adventure comic book. I had just finished a rather ambitious scholarly monograph and was looking to do something creative, artful, and fun with historical storytelling while still adhering to historical methods.

KAPLAN: How does In the Land of the Lacandón examine imperialist narratives? What parallels do you see between the 19th-century imperialist gaze and contemporary cultural or academic encounters with Indigenous communities?

RIJ: We try to draw attention to imperialist narratives by telling an imperialist narrative that is self-aware. So many of our contemporary ideas about race, civilization, hierarchy, modernity, and so on have their roots in stories told about European imperialism’s encounter with Indigenous peoples. Those ideas remain enduring and embedded in our culture today, but there is also an extraordinary critique of them. One need only consider the recent remarkable commentary on empire by Andor, for example.

KAPLAN: Who is Manuel Bolom Pale? What was his role in the project?

RIJ: Manuel Bolom Pale is a prize-winning creative writer from Chiapas. He is an Indigenous Maya and often writes in Tsotsil, his Indigenous language. Our book riffs a bit on who gets to speak, who gets to tell stories, and who gets to make histories, so we asked him to write something creative for the book to help draw attention to these themes. His poem, published in Tsotsil and English, evokes a distinctive worldview from the Lacandón told through multiple perspectives.

KAPLAN: Can you walk me through your collaborative process with Steven Van Wolputte?

RIJ: Steven got involved very early on. I had located the periodicals, film, photographs, and radio lectures which were the base material for the comic. So he got started thinking about that bit while I continued doing research, reading, and writing. Mostly over email and occasionally on Zoom, we’d trade ideas, swap drafts, give feedback, and so on, all the way through. It is important to point out that Steven is an anthropologist who draws. So, intellectually, we understood each other very well in recognizing and developing themes and thinking about how we might integrate those visually into the comic, and likewise what points we needed to develop in the essay.

KAPLAN: How did you settle on a visual style reminiscent of mid-century European comics?

RIJ: My very first scholarly journal article was about comics censorship legislation in postwar France. So I am quite familiar with interwar and mid-century comics, francophone and otherwise. Steven is Belgian with a deep knowledge of comics/BD. From the outset, I envisioned this story as a 1930s Tarzan or Tintin or the like. Our graphic evokes the style of that era and uses the format as both homage and critique.

KAPLAN: Star Trek is quoted early on, drawing an immediate parallel to fan criticism that TOS has an American imperialist bent. How is Gene Roddenberry’s concept of a “Wagon Train to the Stars” reminiscent of the colonial hero-explorer narrative?

RIJ: Captain Cook/Captain Kirk. The Endeavor/The Enterprise. Both are ships full of scientists on voyages of discovery while doing the work of colonization and empire. That brief reference draws attention to how commonly imperial narratives are embedded in pop culture, which is another of the themes we address.

KAPLAN: What sources or archives were most instrumental in developing this narrative? How would a lay person approach doing this type of historical research?

RIJ: That’s tough. Many of the materials I found were scattered around archives and libraries in three countries; for example, the radio transcripts that proved especially valuable were in a folder in a box in a small archive in Paris. Still, vast numbers of newspapers and magazines have been digitized and are available and searchable through various interfaces. Sometimes you have to apply for access, at other times there are fees. But that is something one can do from anywhere with good internet and relentless keyword searching. Also, I want to note that a lot of historical research is secondary: that is, we read the work of other historians–you learn lots, understand your materials better, and they lead you to other primary sources. Read books everybody!

KAPLAN: The graphic novel draws attention to imperialist narratives of authenticity and the harm they cause. Why is it valuable to examine history from diverse perspectives?

RIJ: History itself is human-made. It is an evidentiary study and interpretation of the past, which means that people have created historical narratives particular to specific worldviews. We quite explicitly wanted the reader to think about the history of knowledge production: anthropological, scientific, historical. The broadening of whose histories are studied and whose stories are told helps to understand the past more expansively and more deeply for all of us.

KAPLAN: What’s next—do you plan to pursue more graphic histories, or was this a one-time project?

RIJ: I honestly don’t know. For the first time in thirty years, I’m not working on anything. Steven and I had a wonderful time working on this. I’m sure if one of us comes up with an idea, the other will be keen. Because I don’t draw, I’ll need a collaborator!

KAPLAN: Is there anything else that you want to add?

RIJ: We think we’ve done something unique by making use of different literary forms to tell this history: graphic, essay, poetry, and dialogue. We hope readers find it entertaining and illuminating.

In the Land of the Lacandón: A Graphic History of Adventure and Imperialism is now available from McGill-Queen’s University Press.