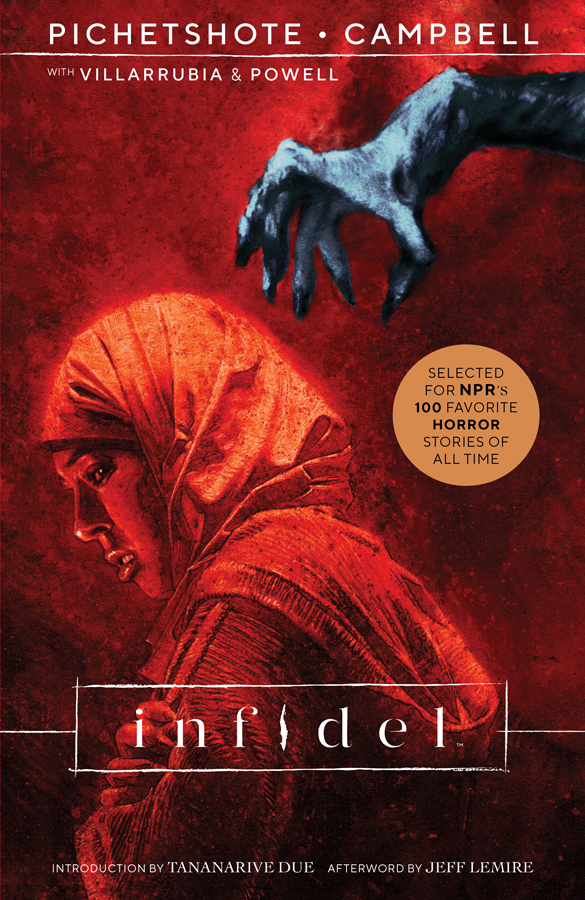

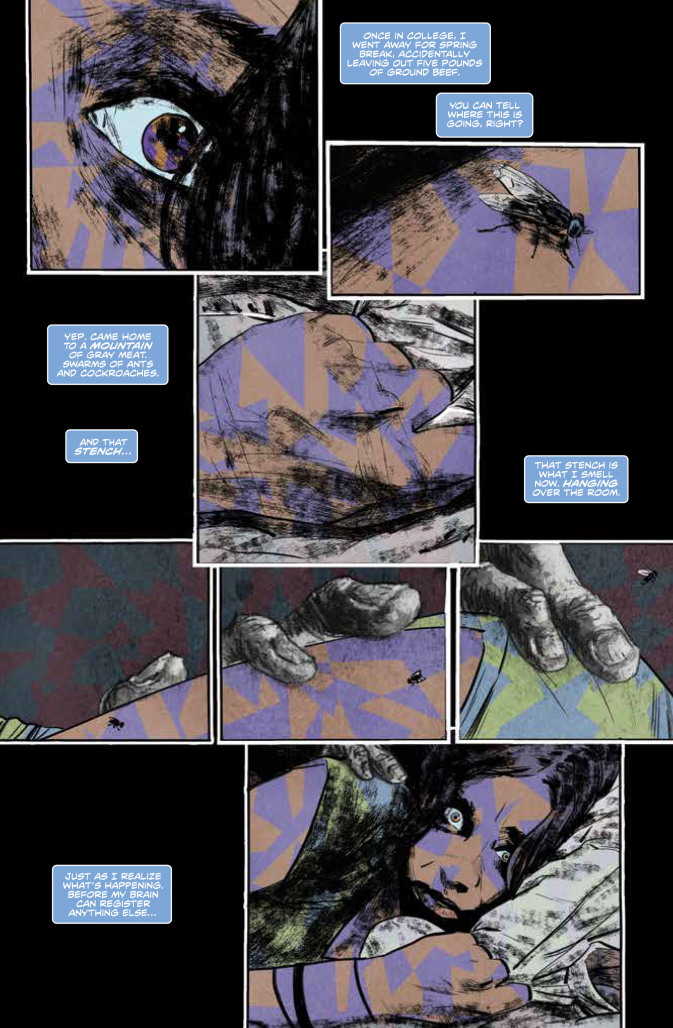

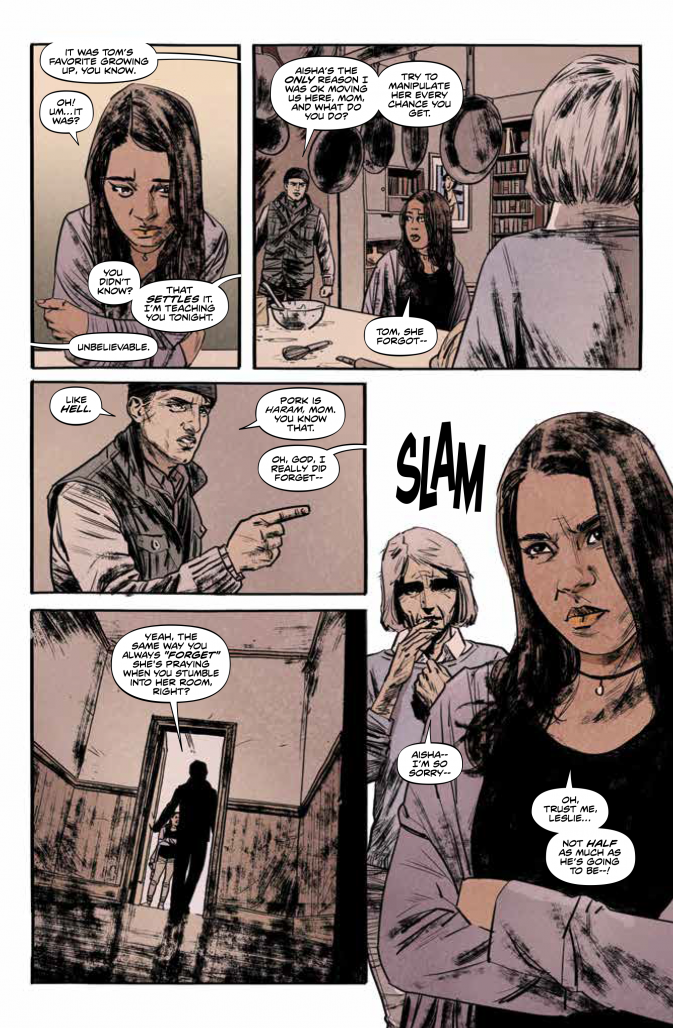

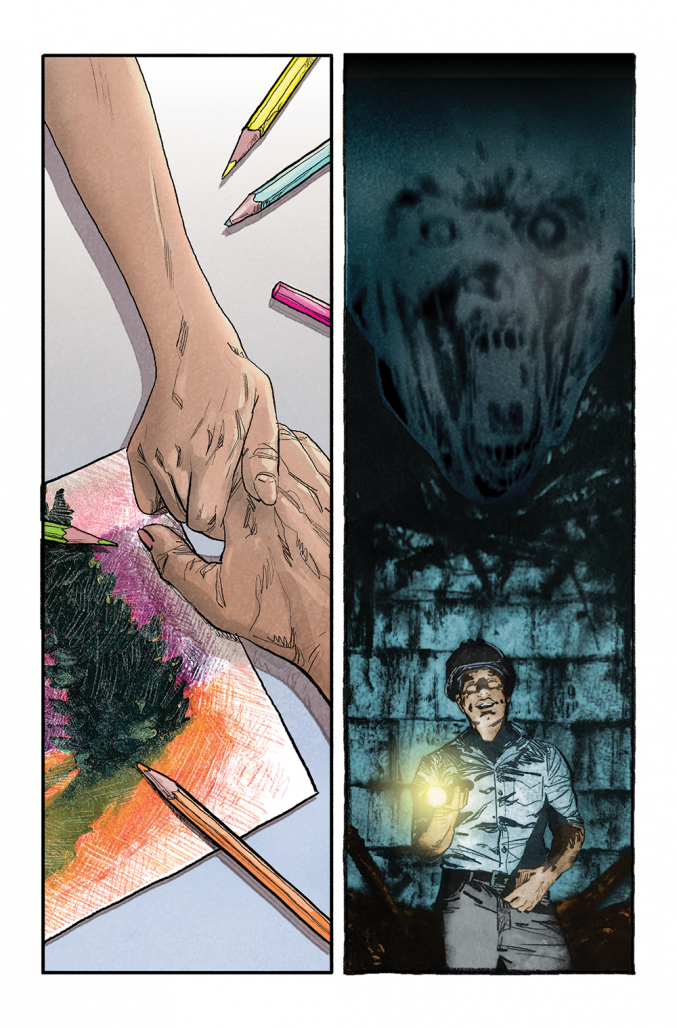

Selected by NPR as one of the 100 best horror stories of all time and optioned by TriStar for a film adaptation, Infidel “follows an American Muslim woman and her multiracial neighbors who move into a building haunted by entities that feed off xenophobia.” Alternately cynical and hopeful; tragic and heroic; Infidel is a story about the conversations we’re scared to have outside– and sometimes even inside– closed doors. It’s a story about race and culture. About the way the way that our actions are perceived can sometimes be misaligned with our intentions and the ways that, as much as we try, we still haven’t figured out how to bridge the gaps that divide us.

Recently, the Beat sat down with Pichetshote and Campbell to discuss Infidel‘s themes and stunning conclusion in advance of its trade paperback release on Wednesday.

Heavy spoilers follow, including an in-depth discussion about the end of the series.

Lu: I hadn’t really considered this the first time we discussed Infidel, but I saw a couple other interviews with the two of you about this series where people were making comparisons to Get Out. Do you feel like that movie’s success helped you to secure an option?

Pornsak Pichetshote: I do. The way I look at it is, creatively, you always want to come in first, but financially, it’s always best to come in second. It’s the glory of coming in second, because someone has done the hard work and paved the way. Everyone’s like, “I don’t know if this is the right thing,” and they’ve hemmed and hawed about it. When you come in second, everyone’s already made up their mind that it is the right thing, and they’re like, “Oh, yes!”

It’s definitely helped us. Creatively speaking, I had this book in my head for a while, way before Get Out. There is a piece of me that’s like, “I wish we could have got there first,” because then we got the benefits of getting first. You get to be a trailblazer, you get to be the first person to talk about all this stuff. Now, all this stuff has already been talked about, but the flip side of getting in second is that people are more willing to spend money on the guy that comes in second than the guy that comes in first. That’s where the Get Out effect is noticeable.

Lu: Aaron, one of the most notable things about Infidel is the way your visuals inform the storytelling of the series– the variety of styles and the ways that the monsters have a separate visual language from the rest of Infidel‘s world, for example. Do you want to be involved in the process of crafting the language for the film?

Aaron Campbell: I would love to be involved, but that won’t happen. They’re like, “We want to keep you guys involved as much as we can through the process.” My idea of that is, “this is who we hired, you’re welcome.”

Pichetshote: I will say, everyone involved, from TriStar to Sugar23, has been super nice, super accommodating. But there’s a line in Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip where Bradley Whitford goes, “I have no reason to believe you, and every reason not to. Why? You work in television.” In this case, movies. That’s the thing I always think of. Everything they’re saying has been fantastic. Everything they’re saying has been great and very accommodating. If all that comes to fruition, it will be an amazing creative experience.

That said, we’re adults. We know how this works. Sometimes they will [let us be involved], sometimes they won’t. If they don’t, the other thing, too, for me, is the book is a self-contained thing. I’m not even saying this politically. I actually don’t have an opinion of how they interpret it. I am the first audience. I’m curious of how they interpret it. I’m curious what they see when they look at it. So much about this book is about differing perspectives and different way people see. I’m curious how they see this book and how whoever they bring in sees this book; whether they’ll see something I didn’t. Will I agree with that? Will I not agree with that? That’s an interesting conversation, I think.

Campbell: Personally, I would just think it would be great if all that ever happened was we got an e-mail or a call from whoever ends up being the screenwriter saying, “I want to pick your brain for a little while,” and that’s it. From there, it would be like, “Okay, you now have all of the cards and all of the components that went into what made the book, now go ahead.” I would be absolutely content with just that.

Pichetshote: I’m curious what they’re going to get. I’m really curious. I’m curious if they’re going to go for a person of color, I’m curious if they’re not; a Muslim, a female versus a male. There’s a lot of different ways they could play it. It’s funny, it sounds political, but I am legitimately so curious and excited to see what they do. Again, my part of it’s done, so I don’t have any vested interest in what they do. I’m just curious to see how this particular part of it gets made.

Lu: Do you worry they might take it down the path they took 21? The movie about the MIT kids that figured out how to count cards in Blackjack. That story was originally all Asian kids, but then it became all white kids and two Asian characters on the side.

Pichetshote: Here’s the thing that I find interesting. If that is the way they go, and I’ve thought this through, I wouldn’t be up in an uproar or anything like that only because I would be curious to see why they made the decisions that they made. As far as I’m concerned, the book is the book. It already exists. You can’t change what we did. If they were to change that completely, I don’t understand how that would be the right way to handle the material. Literally, I don’t even understand what the material is at that point. If they tried to creatively justify it, I’d be curious to hear what the creative justification is. I may not agree with it, but I’d be very curious.

Having said that, it’s hard for me to believe a version [of Infidel] like [the 21 film] exists. It’s hard for me to believe that the right person for the job isn’t one of color, or some combination of that, a light-skinned writer and a person of color as a director or whatever the case may be. Again, I very sincerely mean I’m really curious to see what they do. I don’t harbor any sense of entitlement.

I think part of the self-loathing that is bred in comics is people thinking they only have one good idea. I guess I’m arrogant enough to think I have more than one good idea. If I put one good idea out, they’ll do something with it, and if I don’t like what they do, I’ll move onto the next good idea. If I don’t like what they did with it, in the next good idea, I’ll try to be more involved with it. You’ll burn a lot of calories and worry yourself into an early grave if you think you can control everything.

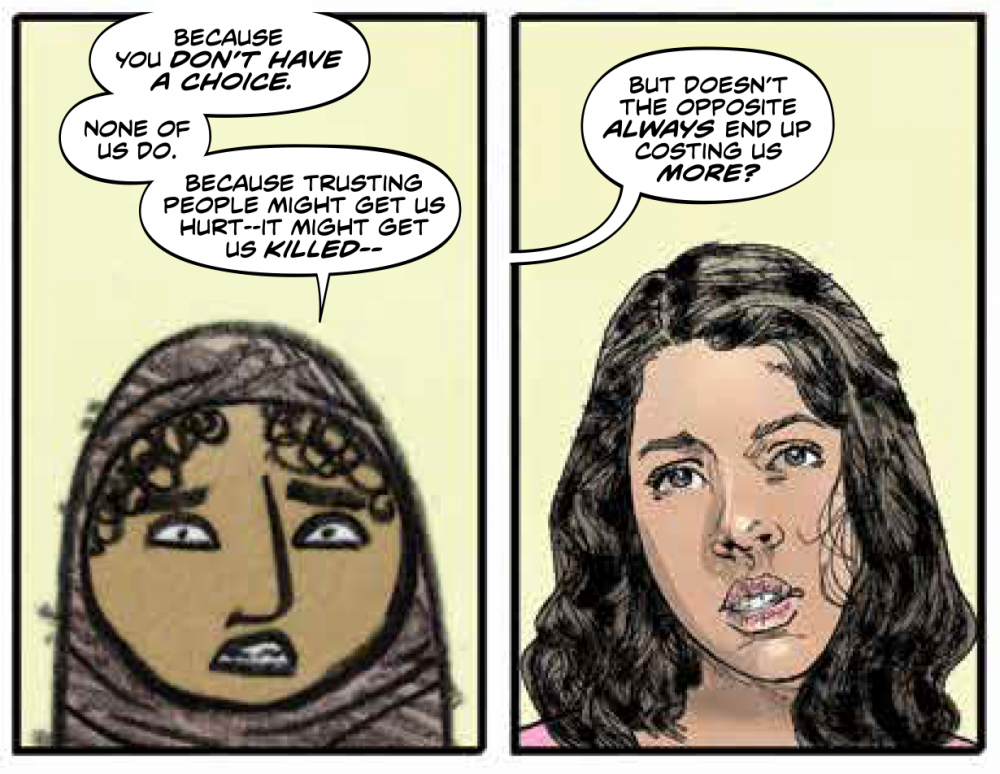

Lu: I think that makes a lot of sense, and I think that’s a healthy perspective to have. To refocus this conversation on the book specifically, I’m interested in the idea of perspective and how central it is to the story of Infidel. There’s a big perspective shift in the middle of the series when we move from following Aisha to following Medina. That’s the sort of thing that I wouldn’t expect, especially from a book that just got optioned. When we think of an archetypal story, I think we typically see one lead that you follow through the whole story, but you don’t do that. You really focus on the ensemble toward the second half. What was the thought process behind that decision?

Pichetshote: When you’re writing a story, you’re always trying to figure out, “what is that thing you can do to keep the audience off balance when they’ve seen so many things?” It’s a horror thing, especially. Lord knows there is a big track record of horror movies, from Psycho to Hostel, that change the protagonist midway through.

So, the place where [a story like Infidel] gets interesting is, if Infidel is a study of racism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia, the next progression of that conversation is taking the character that we’ve related to– the character that we’ve been trained by the story to see right and wrong through– and taking them out of the picture to see what happens to conversations about that person when you don’t have the anchor of that person to emotionally nuance it.

If Aisha is still alive and dealing with all that other stuff, because we like her so much and are seeing the world through her eyes, we dislike everyone else who is credible. Once she’s taken out of the picture, you have a bunch of people just talking about her and they don’t know how they feel. Then, all of a sudden, you’re a little more on board [with them]. You can detach yourself and see the intellectual justifications that each of the different people made.

It’s very easy to say, Islamophobia is bad, violence against Muslims is bad. I’m more interested [in what happens] when we move that needle to the center, in the shades of gray. We know that’s bad. Is this bad? And if we move forward five inches, is that bad? Move forward five inches, is that bad? Do we actually know? That was interesting to me, talking about those characters who are trying to figure it out, groping around in the dark. That is the thing that we gained, I think, by losing Aisha and shifting to Medina. At that point, Infidel really got to be about “how much do we really trust each other? How tribal are we, really?”

Lu: Something that is quite challenging about Infidel is the way that you approach this sensitive topic from multiple angles. I think that there’s a tendency, for fiction and the language that we use that surrounds it, to become more prescriptive. You do risk backlash when you’re not telling people “this is right and this is wrong.” Is that something that the two of you ever worried about?

Pichetshote: Before I answer, I’m curious what your answer to the question is, Aaron. Did you ever worry about it?

Campbell: I worried about it a lot, because I’m your typical cis white male telling the story of a young Muslim-American girl. The issues with racism and race that she faces are not experiences that I have to draw upon outside of the experiences my wife has had as a first generation Mexican American. I felt a certain amount of comfort with the material because of that, but even still, personally, I can’t [draw upon those kinds of experiences]. At the end of the day, I have this philosophy about storytelling nowadays, which is that if we have any hope of bridging the divide that exists between all of us culturally, even right here at this table, it’s important for us to get into the head space of other people. There’s no better way to do that than to tell a story that’s outside your comfort zone because it forces you to try to perceive something from a different perspective.

The process of doing the research [for a story like Infidel]– trying to figure out what is the most considerate way and the most delicate way to tell a story that is representative of what this particular individual would actually go through– opens you up to an entirely new frame of reference the same way that travel opens you up to a new frame of reference. You get yourself outside of the little bubble that you exist in and suddenly you realize these people that are across the corridor, or anywhere else in the world, you understand their history and their culture on a level that you never could any other way.

That’s the way I always think about it– that’s the way I try to approach this kind of stuff. I understand there are certain stories that someone like me should never touch, but I think that there are certain stories that I think it’s important that we start to. If we hope to ever reach a true multi-cultural utopia, we can’t just be there like, “I’m a white guy, I’m going to tell white guy stories. You’re a white woman, you’re going to tell white woman stories. You’re LGBTQ, you’re going to tell those stories.” It would mean that every character in your book has to be homogenous somehow, and you can’t do that.

Pichetshote: It’s an interesting time we’re at as a culture when it comes to storytelling because I think storytellers at this very moment are all trying to figure out what the line is between empathy and exploitation. We want our story to be built on empathy. It’s built on the desire for empathy. To expand that to as logical a degree, that desire to be empathic should incorporate all cultures and people of all faiths.

At the same time, going back to what Aaron said, there are certain places where you are not the right person to tell that story. When you go into that place and you have the arrogance to say, “I don’t have that experience, but I have the right to tell that story,” then you get into the realm of exploitation.

It is a scary thing to be at. I think it’s something that all storytellers are trying to figure out now– where is the right place to land? To go back to your original question, it was something that was scary in terms of the story moves that we made. We’re at this point now where it’s really safe for the white male to be the bad guy, but once you go past that, are you allowed to have this character be the traitor or this person be the spy? What negative messages would [those choices] send?

I don’t know the answers to these questions. The only thing I can do is try to reflect it as truthfully as I can and not offer my own opinion because I don’t know if my own opinion is right.

The other portion is, too, we’re at a time where none of us know what the right thing is. We’re all groping around and trying to figure it out together. All we know is that there exists, in the venn diagram of good storytelling, there is something that exists between empathy and exploitation, where empathy gets as close to [a subject] without treading into exploitation as it can. In there is good, positive storytelling.

Lu: A lot of the story of Infidel focuses on the language we use to discuss sensitive issues. You have these long discussions about how to talk about [things that are difficult to talk about.] Even here, at this table, we’re walking on eggshells trying to pick our words very carefully because we don’t really have the vocabulary to discuss these topics in plain terms that we know won’t necessarily offend one group or another.

This question is for you, Aaron, in particular, because I think that the eggshells are a little bit softer for you than they are, necessarily, for Pornsak and I because as minorities we have this lived experience…I don’t know if I would necessarily categorize it as a shield, but we have a little bit more room to make mistakes and not necessarily be demonized for them in the same way.

So all that said, when you’re trying to develop your language for how to talk about issues like race and xenophobia, how do you think that experience compares to what ours might be like?

Campbell: God, that’s a really difficult question to answer. Again, it comes down to a sense of empathy. For me, I’ve always come from a position where I’m operating from the best intentions. Sometimes the best intentions lead to terrible things. I’m very delicate in letting Pornsak take the lead on a lot of this because then he-

Pichetshote: I get the blame. [laughs]

Campbell: It’s his blame. For myself, for instance, just look what happened with Scarlet Johansson wanting to portray a trans person. It’s like, really, that’s tone deaf. That’s completely tone deaf.

Pichetshote: With the same director she worked with on Ghost in the Shell. That’s what gets me! You can make the mistake. Maybe I could say, “oh, she stumbled into it again”– but with the same guy she made that same mistake!

Campbell: There are surrogates for myself and people in my position in Infidel. There’s Reynolds, the guy who’s good intentioned, but doesn’t really understand what’s happening around him. There’s Tom, who is violently worried about racism, which ultimately results in some bad things happening. Those are the kind of things that I like to explore because these are things that I always think about. Every time I do a podcast, at the end of it, especially about Infidel, I sit and just worry. “Did I say something stupid? Did I talk too long? Was that insensitive? Am I being an ass? Am I overthinking this?”

I just try to keep all of that stuff in mind as I go forward and say, at the core, this is a story about racism. There are two sides to racism. There’s the racists and the people who are the victims. As a white guy, I probably have a somewhat better insight into the racist side of things because I come from the south. I see that and I absolutely understand how that, especially for my wife, is such a painful thing. And how racism, for me, is an absurd idea to begin with. Racial difference is construct. Cultural difference is obviously much more concrete, but still, even amongst the culturally different; my southern background, my wife’s Mexican background, there are incredible commonalities that exist that allowed my mother and my wife to come together and find communion in their similarity and tear that boundary apart because those similarities exist.

It’s all just construct. It’s all just people that are terrified that that they’re going to..I don’t know…lose their job, their daughter’s going to marry a black guy. It’s all bullshit. Because it’s bullshit, I think it’s important that we all dip our toe into that somehow and try to explore those ideas so we can finally get to that place where we’re all just fingers crossed together.

Lu: That’s not how this book ends, though– and we’ll talk about the ending in a little bit, but the climax of the book– it’s quite grim. Was there an inflection point where the two of you decided that the climax of this story was going to be heroic, but also tragic?

Pichetshote: Honestly, I go back and forth about this all the time with the book. To me, it was all about being honest about what I really thought. There are parts of it where I’m like “was I too grim?” There are also parts of it, where I ask, “was I too hopeful?” I don’t know. To me, at a certain point, when we talk about the climax, it’s about what made the most compelling storytelling. That was the framework I built the climax on, and then I could shade that as I went. The book’s out, and I still don’t know. Depending on the day, I’m like, “I was being too hopeful, I was being too soft, I wasn’t being respectful enough to it.” And then there are days I think that I was being too grim.

That’s so much of what the book is about– that uncertainty. If I came to anything through writing this book, it’s the idea that idealism is like what Winston Churchhill said about democracy: it’s a deeply flawed system, but it might be the best thing we have. That’s kind of where I’ve landed with the ideas about the book. I don’t know if Aisha’s way of looking at the world is the best way to go, but it seems like it’s better than any of the alternatives so far. That’s all we’ve got to work with, so I’ll back that horse.

Lu: The part of the climax that was the most painful thing for me was the moment where Medina has that moment of connection with the ghoul. For a moment, he hesitates coming for her. It seems like they actually see each other as people, but then he goes for her anyway. That was a very stark reminder to me that no matter how similar you can make yourself appear to be to other people, some of them still won’t like you.

Pichetshote: That is exactly a creative choice where I [ask myself], “am I being too cynical? Am I not being honest enough?” That is a perfect example of a choice that made for the best storytelling. There’s an argument where I was wrong in either version I did. I honestly don’t know what it is. At that point, it just felt like the best storytelling move. Then it was like, what does this say about the world? Does this feel honest? That felt like the most honest version of it to me at the moment I was writing it.

Again, if I had been writing Infidel two years from now or two years ago, maybe that story would have gone a different way. I said all throughout the course of writing it, there are moments in the story where I wouldn’t really know how it would go until I got there because it was so much about a reaction of what I was seeing in the world.

Campbell: I considered that moment to be incredibly authentic. It almost represents everything Infidel is about in terms of racism, because again, being from the south originally, I have known a lot of my people from my background–and I’m not calling out family members, but people around my family group who I’ve known, especially older generations who are gone now– who were unrepentantly racist, hated black people, but there’s always that one black person they accept. Because they have that one black person that they like, they’re like, “I’m not racist, I have this guy.”

No, you’re racist. Just because you have found one black person that somehow meets your standard, the barrier is always going to exist because you have chosen, for your existence, that the color black is a disqualifier that has to be overcome. They are always going to be ready to turn. If that black friend of theirs one day does something that they don’t like, then boom. “See? I was right about them all along.” That’s straight edge, right there in that moment [between Medina and the ghoul]. There’s that moment of connection, and then it’s like, “oh no, no, don’t forget who’s in front of me.”

Lu: There’s been an evolution, I think, in the way that a lot of people on the far right talk about racism. I think more and more now, they don’t couch it as a matter of racism– they see it as a matter of assimilation. They always want people to assimilate and they worry about immigration because they say “how are so many people going to assimilate?” And when you couch it that way, even I can see the concern to a certain extent, but I still have to ask, “is this your actual concern?”

Pichetshote: That’s the thing, though, right? For the past 100 years, politically racist legislature has passed under the guise of assimilation and under the guise of jobs. History has always told us it wasn’t about jobs, it wasn’t about assimilation. It’s one of those tricky things, which is definitely a question for a person smarter than me. History has shown us that these arguments don’t hold water. Mexican repatriation, where 500,000-2,000,000 Mexicans were deported out of the countries during the 1930s because jobs were low…that’s not that different from where we are right now.

Not only that, but there are statistics, there are proven studies that show that repatriation act encouraged the Great Depression. That’s public knowledge, but we as a culture choose not to interpret that in how we build our laws and how we legislate. On the one hand, I can say, that is the language and intellectually I understand that there is concern there, but historically I have to say, we’ve also learned lessons from that language and certain people are choosing not to heed them. There’s a little bit, in my opinion, a lie to that justification, as well.

Lu: To go to the ending, the Epilogue. I think that that scene is the perfect example of how well your whole team has worked together on this book. I love that duality between the workers going through the apartment and Aisha sitting down on the table– this push/pull between whether there is hope for us as a society or whether, in the end, people are always going to be this way. How did you work together to build this sequence?

Campbell: We worked on that a long time.

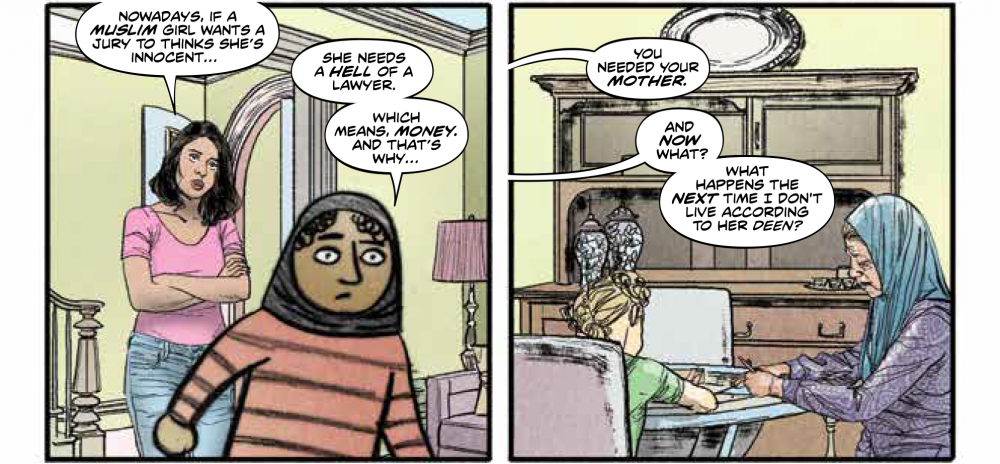

Pichetshote: Honestly, that [scene] was definitely the toughest. There was more work and back and forth on that scene than in the rest of the book, to be totally honest. It was because we wanted to accommodate every group. Because it was the closing scene, because it meant so much, because it had to be…there was a lot of pressure of it having to be realistic in terms of the extra mile Muslims in this country have to go through in the legal system and everything to get the same treatment that we all take for granted. So, on the one hand, there was a pressure to get that right. On the other hand, after everything these characters had been through, they deserved some element of hope. Not just for the characters themselves, but also…because so much of this book was to the tune of political fiction, you also ask yourself, “what message are you putting out there to the world?”

The message we didn’t want to put out there is that “things suck and they’re just going to get worse.” At the same time, I don’t feel confident and I don’t feel it’s my place to say things are going to get better, either. As a result, it became a conversation to involve me, Aaron and Jose, as we really went back and forth. What made the most sense for that ending? What’s the point where we all feel comfortable about concluding everything we had taken the audience through for the past four and a half issues?

Lu: The last page of the book, where you split things evenly and you just have the singular caption, it feels very much like Choose Your Own Adventure kind of book. You decide whether or not this has a good ending or a bad ending.

Pichetshote: That was intentional. I knew that’s how that book would end. I went back and forth in terms of what the imagery would be in the panels, but on the dark side, I knew that when I started the book. The bright side– that went back and forth a little bit. I think it came pretty close to what I originally designed, though. I always knew, to me, that this was the only honest way to end the story considering I didn’t feel that I was the right person to say which way the world was going to go.

Lu: Do you two hope to tell more stories together in the vein of Infidel?

Pichetshote: Definitely. It’s how my brain is built. I love genre and I love the tropes of genre. I’m also very interested in politics, so it makes sense to me to fuse the two together. I’m definitely thinking about that for the next book and I definitely want to work with Aaron again. He’s such a great partner to work with.

I can’t talk about my next book, but it is definitely something that I’m putting together as we speak. It is something that involves genre and politics. We’re definitely looking at things that we aren’t looking at [in Infidel].

Campbell: The one thing that Infidel has done for me is that it’s redirected and refocused my career completely toward horror and what is possible with horror and I love it. It does allow the experimentation. It does allow me to have an actual voice in the conversation that’s happening right now with all of this awfulness instead of just being the angry Facebook reactionary going, “Goddamn it, look at how angry I am!”

This book has had an actual impact on people. I’ve met them at cons, especially young women who are of a Pakistani and Muslim background. I’ve met several of them who say, “Oh my god, I love this book so much because this is my life that you’re talking about. I come from a very fundamental background and I don’t know where I fit in that. I don’t know if I want to wear a hijab or if I want to practice the way my parents practiced.”

There’s a whole generation of people in that culture who are going through the same thing that your regular white people like myself, who grew up very fundamentalist Baptist, are trying to figure out. “Where the hell do I fit? What do I believe?” That has been incredibly rewarding.

I just love horror. Horror has the ability to deeply take hold in your lizard brain and stay with you forever. 14 years old, I discovered H.P. Lovecraft and it was like he was writing right to me. Not the racist stuff, but just the fear. It was that fear of being a person alone in a broiling chaos– what if there is no meaning to anything? What if there is nothing beyond the veil; it’s just the void and this is all chaos and you have no hope of redemption? Those are issues that horror addresses existentially that I am incredibly fascinated by. You can’t address that in a superhero book or a pulp book, what I used to do a lot with stuff like Green Hornet. Those are adventure tales. It’s fun, it’s diversion, it’s release. I want to grab hold of you and shake you awake.

Lu: Last question– in the back of each issue of Infidel, you address heartfelt letters from the readership and talk about the conversations you’ve had with readers at conventions and elsewhere. What has the response been like?

Pichetshote: They’ve been great. It’s great to hear that people respond and relate to the book. This is my deep cynicism rolling in. When we made the book, I didn’t know if anyone would care, honestly. Partly it’s because it’s a new book and why would anyone care, but also because of that conversation about race. Do people really want to have it? Just the idea that people are engaged, and people want to talk about it in so many ways…

A lot of the subtle depth of Infidel is not load bearing. You can read the story without any of that interpretation if you want to– you’re just missing a lot of what the book is about. The fact that people like you and other people out there are willing to read as much into it [as you have] is enormously gratifying. I didn’t want to do a book where you needed to figure out all this stuff in order to understand it because then it would start to feel like a test and that’s not what I wanted. The idea that people are willing to go there and look at it that way, though– that means a lot. The fact that it’s people of different races and ethnicities, that was really reassuring and affirming a lot of stuff that I was worried about, that the book worries about. I am continually amazed that there is anyone besides my mother who is interested in reading this book.

Campbell: That might be more than I can say for my mom.

Pichetshote: You’re right. I might be giving my mom the benefit of the doubt.

Lu: Well, if there’s anyone to give the benefit of the doubt to…!

Infidel‘s TPB hits comic store shelves this Wednesday.