by Alex Dueben

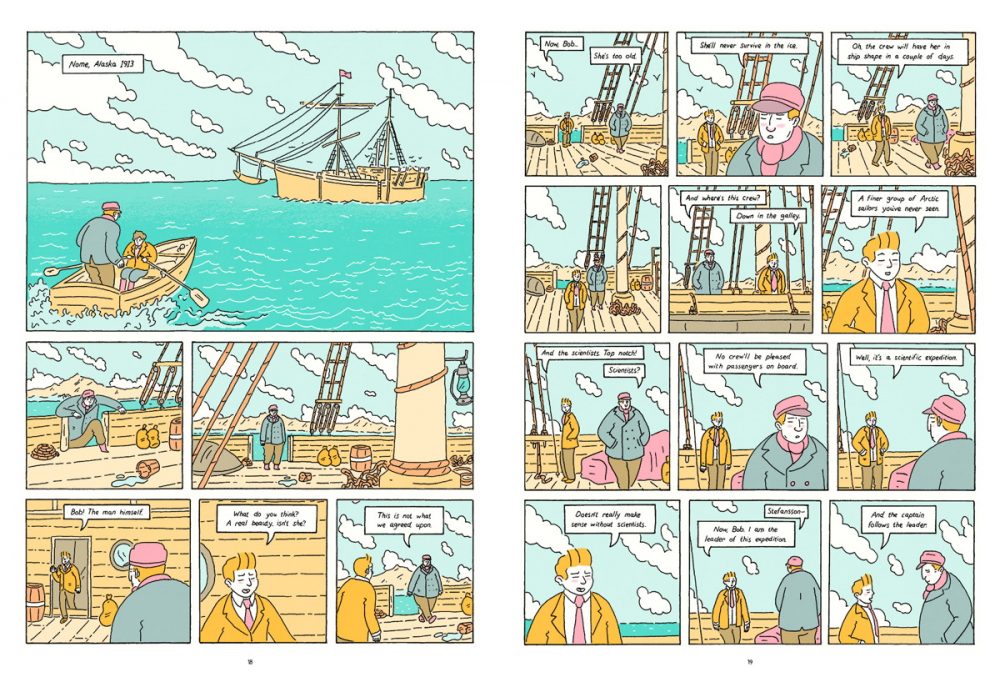

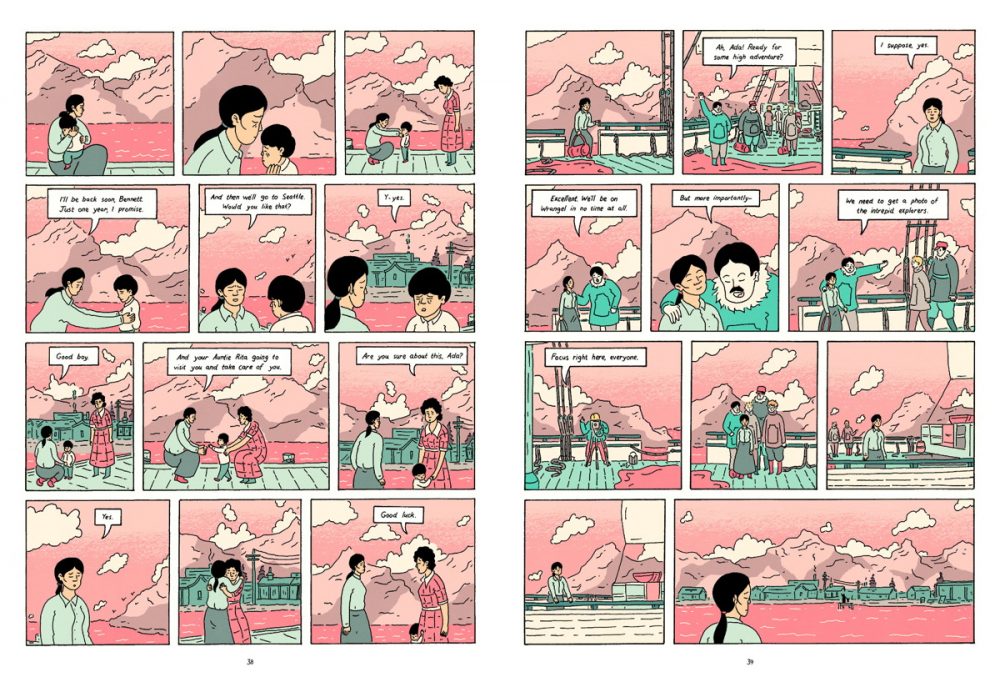

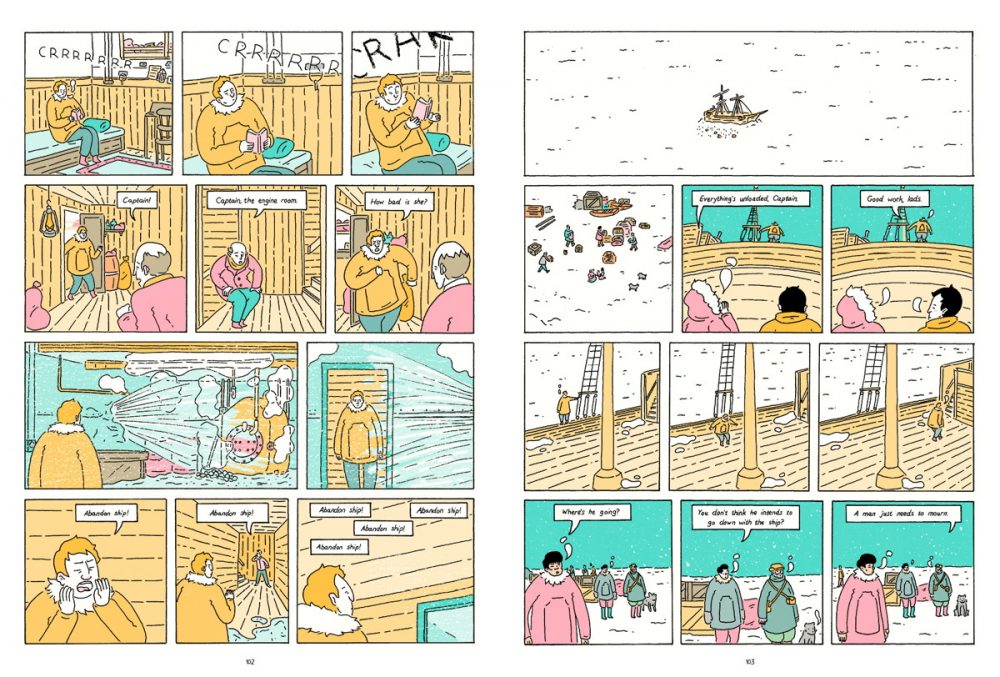

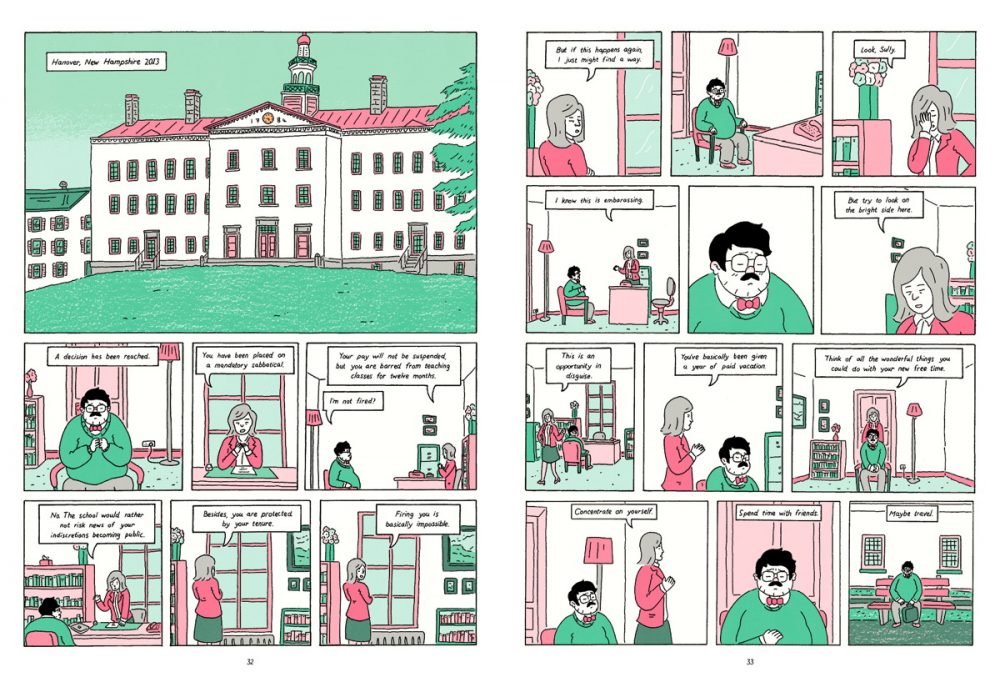

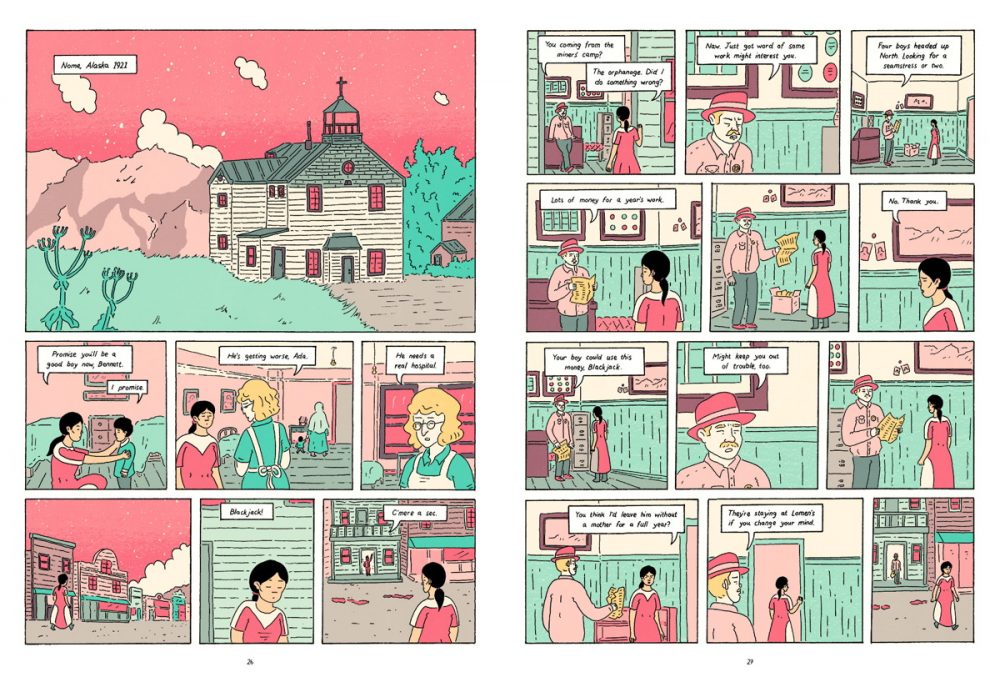

Luke Healy’s graphic novel How To Survive in the North has just been released by NoBrow, but it’s already started to receive awards. Publishers Weekly gave it a starred review and named it one of the best books of 2016. It was a selection of the Junior Library Guild. It is not, despite its title, a “how-to-book.” In fact in detailing two separate Arctic expeditions–in addition to the life of a contemporary professor–it could be best describe as “how-not-to-book.”

The book is Healy’s first full length graphic novel, but the Irish cartoonist has been working in comics for years now. He graduated with an MFA from the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont. He won a MoCCA Fest Award of Excellence for Of the Monstrous Pictures of Whales, His comic The Unofficial’s Cuckoo’s Nest Study Companion was nominated for an Ignatz and his work has appeared in VICE, The Nib and other outlets.

Alex Dueben: Where did the idea for How To Survive in the North start?

I clicked through to her wikipedia page, and read her story, which I thought was interesting, and just sort of filed it away in my brain. Years later, when I was studying at The Center for Cartoon Studies, and it came time to decide what I wanted to do for my thesis project, Ada’s story came back into my mind. After a little research, I learned that a lot of primary sources of evidence relating to her expedition, including her almost 100-year-old diary, were available to the public in a library only ten minutes drive from where I was living. I couldn’t turn down an opportunity like that.

Dueben: Have you spent time in the Arctic?

Healy: I haven’t. I’ve done some snow travel and backcountry travel in the mountains, but never quite so far north.

Before starting work on How to Survive in the North, I really hadn’t any particular interest in the Arctic. Now, I have a soft spot for those kinds of stories, and hey, if the opportunity to head up there ever comes, I’ll jump at the chance.

Healy: The 1913 expedition, which was called The Canadian Arctic Expedition, was a scientific expedition. Several ships were going to sail north from Alaska to explore the Arctic Circle, and gather scientific data on the area. It was the largest arctic expedition up to that date.

The 1921 expedition, called the Wrangel Island Expedition, is a little murkier. A crew of only five people were sent to Wrangel Island, officially to settle the island, and claim it in the name of Canada. Though, the Canadian government was not on board, in fact the attempted settlement caused a lot of tension with Russia, as it was seen to be an aggressive move on behalf of the British Empire to encroach Russian territory.

It’s believed by some, myself included, that the real purpose of the 1921 expedition was to prove true Vilhjalmur Stefansson’s theory of “The Friendly Arctic.” Stefansson, who had organised both expeditions, wrote a book claiming that anybody could survive and even thrive in the Arctic with only the most basic of knowledge. I think it’s likely that he sent up five inexperienced people, so that upon their triumphant return he could point to them as proof of his theory. Sadly, that triumphant return never came.

Healy: In a word, yes.

Dueben: There are three stories in the book, those two and then the story of Sullivan Barnaby. Could you talk a little about who he is and why you needed his story in the book?

Healy: Barnaby is the protagonist of the only purely fictional strand in the book. He’s a professor at a New England university who is placed on sabbatical after having an affair with one of his students. His role in the book changed a lot over the course of production. Initially, he was written into the book to act as a modern day conduit for information that couldn’t be known to the members of the expeditions. He was there to provide context, information and exposition. He was basically a researcher who stood in for me, as I researched the facts of these expeditions. However, as time went on, I decided I wanted to alter his role in the book. He, and his story now serve as more of a narrative and thematic device to draw forth some of the more meta-textual points that the book is trying to tackle.

I’m pretty fascinated by the relationship between fiction and non-fiction in media at large, but particularly in comics. I think that while everybody has to draw their own line between what does and doesn’t qualify as non-fiction in any medium, I think that in comics that act is particularly essential.

Dueben: How much research was required for this project?

Healy: A fair amount. I spent a good few weeks at the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College reading through, and recording primary sources for later reference. I read diaries, memoirs, newspaper clippings, magazine articles, correspondence etc.

Half of Ada Blackjack’s diary was written in the empty spaces of a camera film order form. I imagine because she had run out of paper while she was marooned. It still fills me with disbelief that I was just allowed to go in and handle these documents. Some were over a century old. Some were cracking in my hands as I turned the pages.

Dueben: What was the most surprising thing that you discovered while researching the book?

Healy: That basically every Arctic expedition ended in disaster. I’d always assumed that the disasters were they exceptions, when actually they were the rule.

Healy: I’m not an expert on the broader history of Arctic travel. I’m sure somebody more well-informed has presented some possible reasons. But I think they probably did it for the same reasons people still do dangerous things. A sense of curiosity or restlessness, or duty to their country maybe. A belief that the benefits of any discoveries could outweigh the possible risks. Maybe some of them were ill-informed about the realities of Arctic or Antarctic travel. I mean, the media at the time seems so bold and propagandistic in a lot of ways. The people who returned successful were treated like heroes.

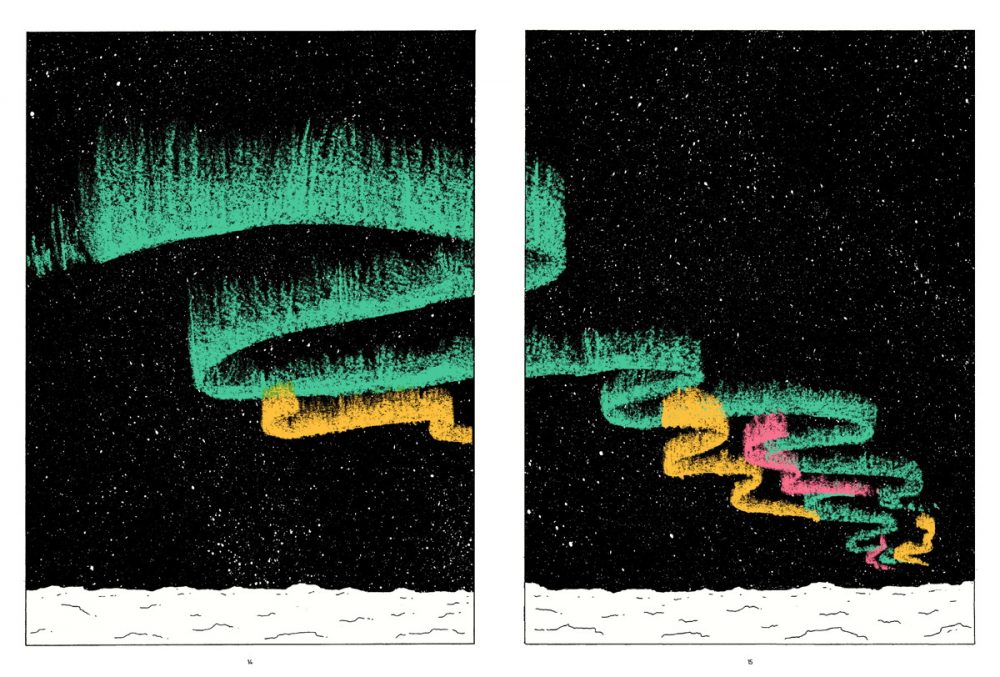

Healy: Well, my first impulse was to go in the opposite direction of what a reader might expect. I think often people’s first instinct when telling a period story in comics is to go for dull, muted tones, or sepia. Which is so boring! And just ugly besides. If you’re telling a story set in the real world, then you should use bright colours, because the world is bright and vivid. Especially if your story is set in nature.

Now this book definitely pushes the brightness of colour past real world levels. I wanted the art of the book to be reminiscent of old kids adventure comics, something along the lines of Tintin or Asterix. I wanted readers to start the book excited to be reading these tales of adventure, to reflect the initial excitement that followed these expeditions. I wanted the harsh reality of the stories to settle in with the readers later, as it did with the characters.

Deuben: I also wanted to ask about the page layouts and design because you have dense page layouts with this four tier layout.

Healy: This is just another visual reference to comics like Tintin. The density of the pages also just reflects the natural pace of how I tell stories. I like to live in an event with lots of individual moments before moving on. For me, when a reader turns a page in a comic, they’re really moving on to another event. Page turns mark progress in a big way, so I like to include a lot of panels on each page, to give me space to stretch out in a moment before we move on.

Dueben: The book managed to convey this sense of vastness, of people being small in this landscape, but also the almost claustrophobic sense of being in these small spaces, either in tents or on ships and alternated between those sensations.

Healy: I’m glad to know that the intended effects landed for you!

I’m definitely interested in panel composition as a storytelling tool. One of my pet peeves in comics is when the cartoonist constantly crops in on the characters really tightly. I have a general rule for all of my work, in school we jokingly called it the “Tiny People” rule. For more than half of the panels on a page, a character’s full standing height should be less than half that of the panel.

I apply this to most of my work, because I think a full body can communicate a lot that a medium distance or close up “shot” can’t. I just chose to amp this up for How to Survive in the North. Lots of the drawings of people in the book are so small, they’re only a couple of pen strokes. This was mostly used to communicate the tiny-ness of the people lost in the vast snowy landscaped of the book.

Dueben: I’m curious about your background because you’re Irish (correct me if I’m wrong) and you went to CCS. How did you end up a cartoonist?

Healy: I am Irish, yes! I grew up in Dublin, and I currently live there. I wasn’t super interested in comics until late secondary school or college, when a friend of mine introduced me to webcomics. We didn’t have much of an industry here at that time. We still don’t really, but things are starting to take shape here.

I started making my own webcomic at age 18 maybe, and just really enjoyed it. When it came to deciding what I’d like to do for a living, I settled on comics, and applied to CCS.

I’ve definitely worked in other media, I used to be a journalist, and I’d like to expand into other media again in the future for sure. I’m happy as long as I’m creating really, but for now, and the foreseeable future, comics is the place I’d like to be!

Dueben: So the book is called “How To Survive in the North” and while I don’t think anyone will assume it’s self-help, do you have any advice or suggestions for surviving in the North? Or just winter.

Healy: Just keep moving. That’ll warm you up.

Thanks, Luke!

Nice interview and samples. I liked Bertozzi’s SHACKLETON, so I almost pre-ordered this from Previews. But since NoBrow decided to use a mousetrap (that “C: x-1-z” disclaimer meaning they can change any specs including upping the price), I decided to wait and see… And until then, maybe the library will get one!

Comments are closed.