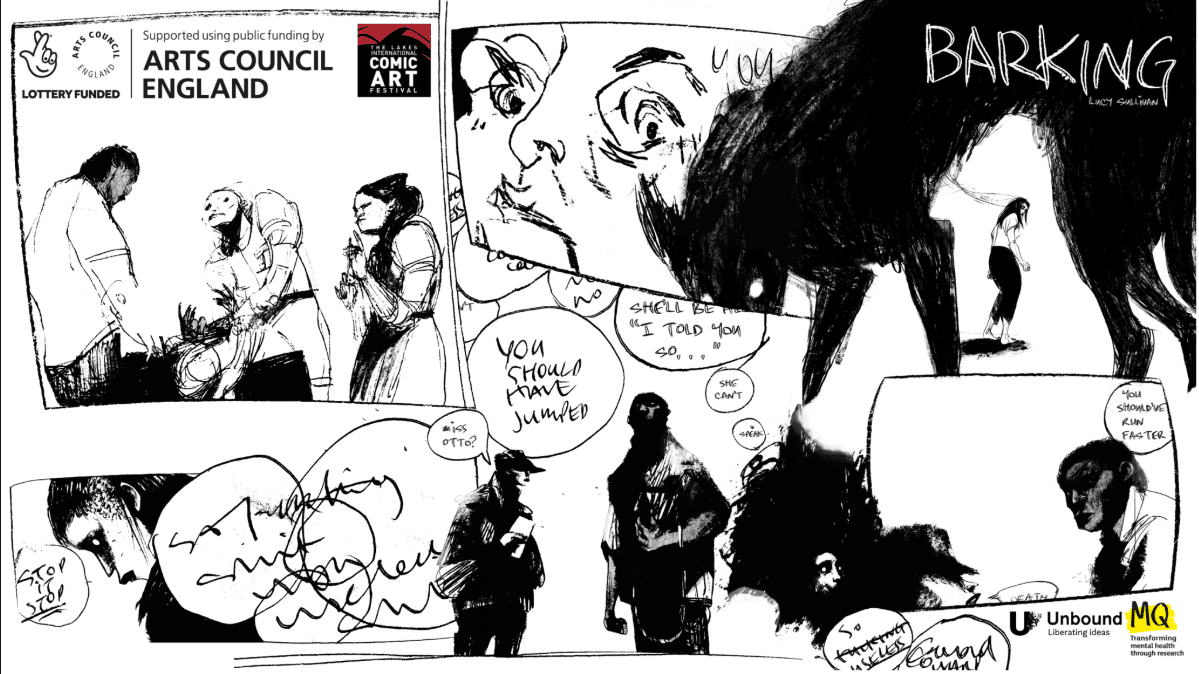

Barking is a visceral, harrowing read. Bold and unflinching, it stands out as one of the best graphic novels of the decade so far, a must-read and an incredible exploration of mental health in a way typically left untold in media. Most recently released by Avery Hill Publishing, Barking is the result of years of work by writer/artist/activist Lucy Sullivan. A firm fixture of the U.K. comics scene and one of the biggest advocates for comics you’ll ever meet, Barking is, in many ways, Sullivan’s own experiences straight to the page.

The Beat interviewed Sullivan to unpack Barking and her work promoting comics in the United Kingdom.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

JARED BIRD: Hello, and thank you so much for your time. Barking has had a long road to publication, but most recently came out last year from Avery Hill Publishing. To those unfamiliar, how would you describe Barking?

LUCY SULLIVAN: It is a tale of grief, depression, ghosts, and a massive phantasmagorical dog. It’s loosely based on my own mental health issues in my 20s. I had a kind of breakdown after my dad died—how I felt and how I behaved wasn’t like what people prescribe to depression. I was really, really angry and very social. I was getting myself in all sorts of trouble, leading to a disastrous night out, after which I ended up in therapy. The therapist told me I had a case of grief-triggered depression and anxiety, and I had no idea that it could manifest in that way. Usually, depression is portrayed as people with their heads in their hands, but I was the complete opposite of that. I was told I had a “male depression,” an unusual concept—how is it gendered? That’s just bizarre to me. In Barking, I wanted to talk about that, how grief manifests, and how long it takes to hit a crisis, because mine came eighteen months after my dad died. At that point, people expect you to be over the death, but you can never really be over it.

I also had some friends who had been sectioned. I wanted to talk about how they were treated in the mental health wards, which I have a big problem with. Our mental health system is built from Bedlam, added to and nominally improved upon; it’s not a great foundation block to start from, laughing at people in crisis. I wanted to explore that through a critique.

However, I found it hard to draw myself. I kept being too nice, softening the edges of my behavior. I was hard to help at the time, so I invented a character and put it through her: Alix Otto; she’s hearing the dog, and then he manifests out of the floor, hounds her down, and she ends up sectioned. Barking is about her dealing with being sectioned, hearing and seeing this dog that no one else can, and the reappearance of her dead friend, who’s also joined her in the hospital. It’s a ghost story, a critique on social concerns and the mental health sector, with a lot of folklore mixed in. I’m very influenced by An American Werewolf in London and narratives like that.

BIRD: You can definitely do worse with influences than An American Werewolf in London.

SULLIVAN: It’s a classic. I saw it when I was six or seven—really, really too young. But I found it comforting that he could still talk to his dead friend, so it sat in my mind. When you die, you’re in the mirrors. In Barking, she floats on the ceiling, and Alix can still converse with her. A huge part of grief is not being able to finish those conversations, the things left unsaid. Part of coming to terms with a death is finishing those lost moments, albeit to yourself.

BIRD: A huge part of how mental health and illness are portrayed in popular culture is that there is an ‘acceptable’ way to explore them, and an ‘unacceptable’ way. It’s very much an unspoken thing. You see works of art praised for how they explore mental health and mental illness, but a lot of them don’t explore some of the very real problems there. What you mentioned earlier about grief showing as an angry depression, for example.

SULLIVAN: People think, as I did then, that it looks a certain way. I was trying not to have any of those tropes in my book, like people sitting in corners, with heads in their hands, or hiding in bed away from the world. That is precisely how it is for some people, but I think we’ve also gotten into a trope with it. One that kills me is narcissism being used in a way that’s the total opposite of the myth, which is probably about nature and using the gifts you have when you have them. Narcissus was beautiful and should’ve used it, but didn’t, so nature took him back. It’s not just about him looking at himself in the mirror all the time, or horrific people like that bloody orange man-baby. It’s about trying to widen that concept, and not limit it.

Grief is different for everyone. Mental health is different for everyone. I wanted to open that conversation and make it a broader discussion on what happens when your life falls apart and when you’re really hard to help. I was spiky, aggressive, and always picking fights with people. I worked at a pub, and I’d pick fights with massive blokes when I was drunk. Normally, they’d tell me to shove off, but one night, they didn’t, and it was bad. One of our bouncers, who had been in jail three times, told me I had an anger problem and needed to get help. He’d call me after every session with a therapist, asking how it went and how I was doing. Sadly, he didn’t heed his own advice and ended up back in jail, but it was amazing to have his support and someone who recognised it for what it was.

BIRD: What’s it been like to work with Avery Hill Publishing?

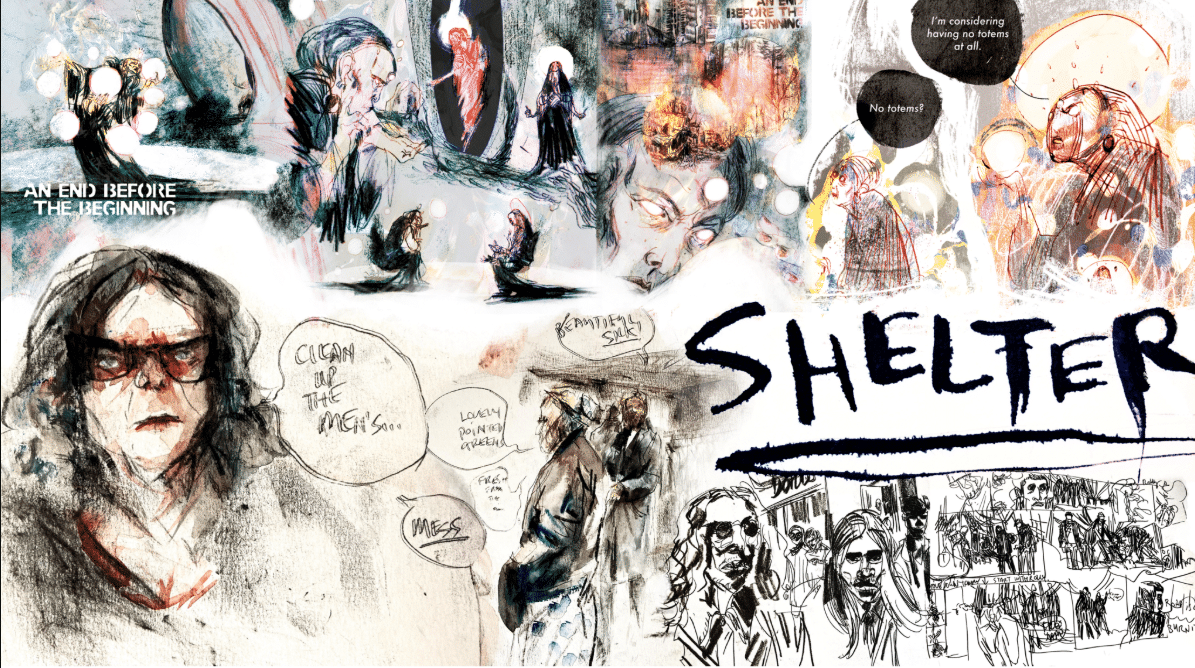

SULLIVAN: They’ve been fantastic. My first publisher, Unbound, was a horrific experience. I had a great editor, Lizzie Kaye, but then she was sacked as we were going to print. They were downsizing and made her redundant, so I had no comics editor at the end. The publisher messed up the print run, which got really bad, so we couldn’t let the books go out. I managed to get Barking reprinted, but it took a lot of legal threats to make that happen. I sold the 1.5K print run to end my contract with Unbound and got my full rights back. It then took three years of talking to various publishers. I had no books left of a critically acclaimed comic that had no publishing home or future, and then I chatted to Ricky Miller at Gutter Lizards, a small press fair. It was in a room above a pub. Ricky picked up my other book, Shelter, and emailed me if I had any more stories because Avery Hill was interested. I said yes! – I’m a big AHP fan, and told them Barking also needed a home. They took it on, and it’s been a dream to work with them. They’re a small team, and everything’s done part-time, but they work so hard, and it’s been such a pleasure. I’m very happy to be a part of their canon.

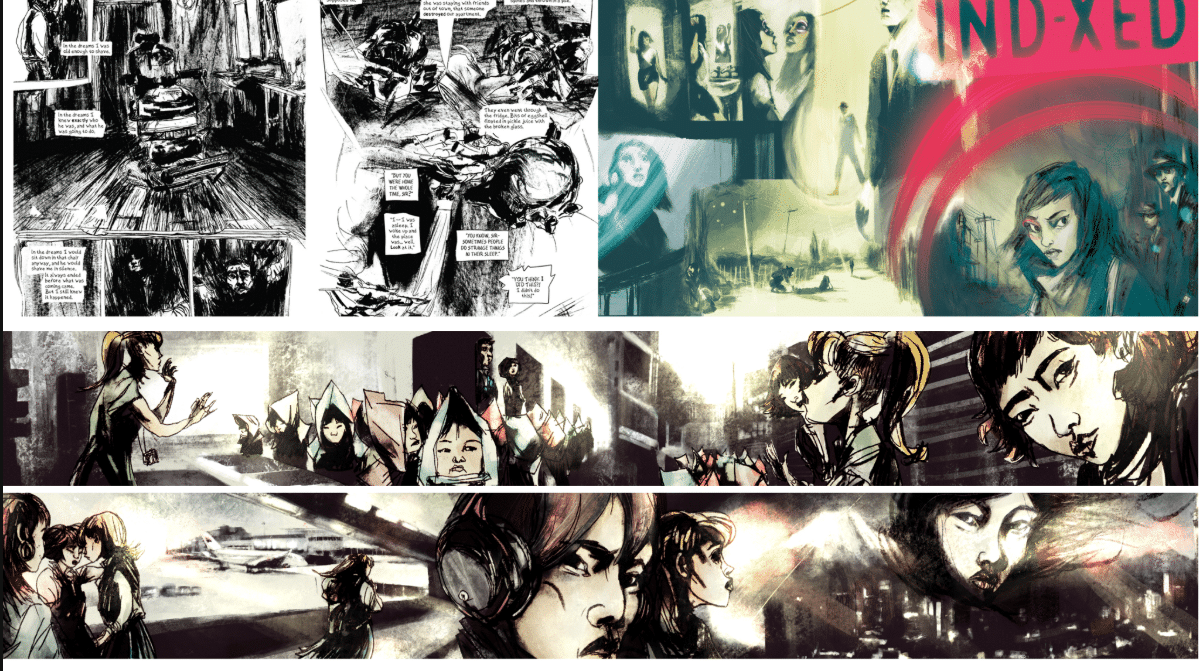

BIRD: Your distinctive carbon and typewriter sheet technique leads to one of the most unique visual sensibilities in comics. How did you develop that style?

SULLIVAN: I used to teach location drawing at a university. We’d go out on-site and have to draw the buildings and the people there. One of my students, Hannah Simpson, brought these carbon typewriter sheets; she’s a fantastic illustrator, and I was intrigued. It produces this lovely mono-print texture. It’s like tracing paper, almost. It looks like a black piece of paper, and you have to press on it, leaving the impression of carbon behind like transfer paper. I was sketching the ideas for Barking and was initially determined to do it in biro, but it was taking me forever to colour the black dog. I asked her if I could steal that technique, and she said, “Of course!” So I tried it for the dog. I could use my nails, sticks, and old dip pens, which were used for lettering. It quickly became a part. You can’t see what you’re drawing, so it frees me up. Barking was such an emotive book, so personal, the carbon meant I could just free sketch and really go for it, and now I find this technique hard not to use. It’s definitely become my thing. Places like here at MCM, when people come to get a book, I can show them how I draw firsthand, and you can see the reaction as you lift it, to reveal. It’s lovely when you get wowed reactions.

BIRD: It blew my mind when I first saw it. I just assumed it was black on white paper, so when I saw the black paper and you pulled it off, I was like “Wow!”

SULLIVAN: My friend, Davidt Dunlop, says it’s witchcraft. I quite like that, we will stick with that!

BIRD: As we discussed earlier, Barking explores mental health and illness in such a vivid and poetic way while still feeling deeply relatable and accurate. Do you have any advice to creators who wish to discuss serious topics similarly to what you did with Barking?

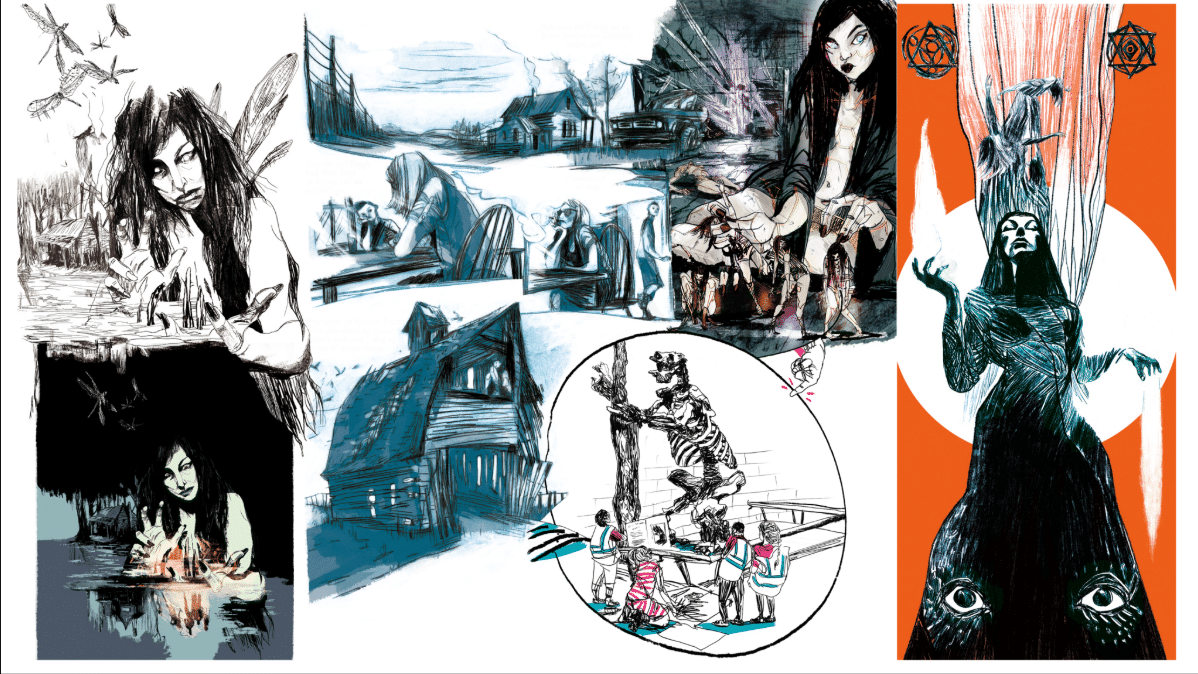

SULLIVAN: Some people can be really good at putting themselves into their stories, like Zoe Thorogood, who does it with such flair, but that might not be something you also feel comfortable with. Like I said earlier, I didn’t. When you take folklore, fiction, and things that people already recognise and link them to what you’re trying to convey, I think it can be a great way to get in touch with readers. Our minds are already educated with fairy tales and such kinds of narratives. You can use those structures and put your experiences into them. It can be a great device. If it’s a difficult topic, you can deliver it under the radar; don’t shove it in their faces, but explore it by allowing inquisitiveness. I find that people are much more open to talking about it if something challenging is delivered through fiction.

When I was making Barking, I thought I’d have a specific type of reader—people who like autobiographical comics and books like that—but my readership has ended up with more people who like horror and fiction. My comics resonate with those aspects of storytelling, which is excellent. I’m fortunate with my readership, who seem open to challenging topics and enjoy the mix with folklore as much as I do.

BIRD: I was working on something recently that was autobiographical in nature, but I also had that disconnect where I wasn’t sure I wanted to put myself on display.

SULLIVAN: It’s hard.

BIRD: It really is, and it’s hard to portray yourself without your own thoughts on yourself influencing it too much.

SULLIVAN: You’re having a conversation with yourself, about yourself. It gets very meta!

BIRD: I had to divorce it from myself a little bit.

SULLIVAN: That’s why character is a great thing. Alix in Barking is me, but making her a character allowed me to go a little further with the honesty about what she was experiencing. I don’t think I would’ve gone as far without it. I put in a sexual assault that happened to me. I couldn’t have drawn that as me, even though it’s entirely the same experience and circumstances that happened to me. Using Alix meant that I could do it. Make a character! Think of it as an alter-ego.

BIRD: You contributed artwork to the film adaptation of Max Porter’s Grief Is The Thing With Feathers. How did that come to be?

SULLIVAN: I’m so excited. It was an instance of complete serendipity. I read Grief Is The Thing With Feathers when I was finishing Barking. I was following Max Porter on Twitter, and he reached out to me about getting a copy of Barking, back when it was still quite challenging to get a copy of it because I had them all. And I told him that I’d read and loved his book, and it was a huge inspiration. I offered to send him a copy, and in his exact words were “Fuck that, I’ll buy it, but it better be good!”

BIRD: No pressure!

SULLIVAN: Right? Luckily, he loved it. When they started doing the adaptation, they decided to change Dad’s profession from being a Ted Hughes scholar to a graphic novelist. Dylan Southern, the director and screenwriter, had also read Barking, and so when they needed an artist, I was one of the names on the list. During the pandemic, Dylan and I had some chats on Zoom, but the world went a bit mental, and it went quiet. At the end of 2023, Dylan emailed me out of the blue asking if I was still up for it, and I immediately agreed. He lives near me, so we went on a walk around a Victorian cemetery and just chatted through it. He’s a huge comics fan. He grew up loitering in comic shops in the 1970s and was very keen to get everything about being a graphic novelist right. He offered me the job of creating all the art for Dad. Benedict Cumberbatch plays Dad, so we had a drawing lesson, with the carbon as it’s a specific technique. Dylan, Max, and I have all lost our fathers, so we are all bringing that real experience to the film. It’s such a labour of love. I created all Dad’s on-screen art in the film, including sketchbooks, book covers, paintings, and all sorts. Cumberbatch was a great sport and really took on all that I was saying, and it was an amazing experience. My favourite part is CROW, a giant crow man, which is how Dad manifests his grief, like the dog in Barking. It’s an actual person in the film. They built a suit, based on work by the sculptor, Nicola Hicks. The performer for it, Eric Lampaert, is on stilts and puts on an animatronic crow’s head. It’s wonderfully creepy, Eric’s such an amazing physical performer. Crow is voiced by David Thewlis, with an amazing rest of the cast including Sam Spurell from Fargo. He was the terrifying haircut dude and an incredible actor. I’m really excited for it to come out. They’ve just secured distribution for the UK and Ireland, as well as the US and Canada, to be released in October. I’m assuming it will be released at a similar time here, so look out for news soon. I’m in the top credits, so feel free to cheer when you spot me!

BIRD: You’ve been working with the Lakes International Comics Festival to do outreach projects across the United Kingdom and other countries as well. Has that changed how you view the emotional impact comics can have?

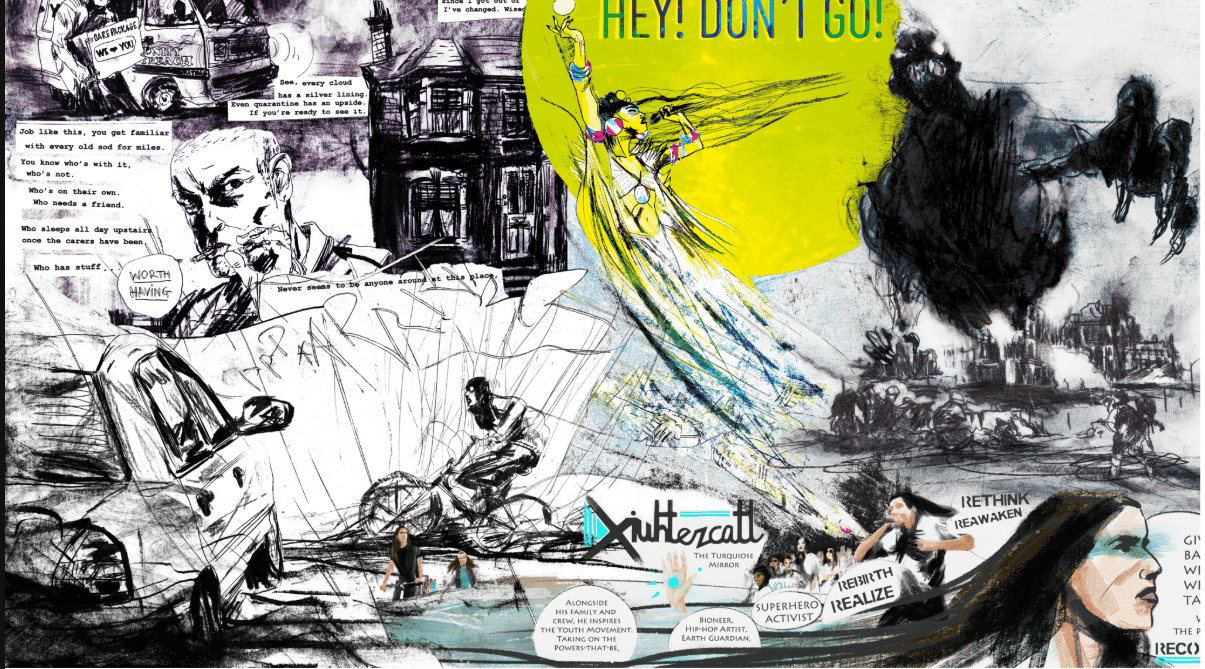

SULLIVAN: Yeah! It’s been really astonishing. When you go to the Festival itself, it’s quite intimate and doesn’t have many exhibitors. It’s not as big as Thought Bubble, but it is very international. I’ve been an exhibitor and I’ve been a guest, but I went to the Philippines with them last year alongside Mollie Ray. Seeing how Julie Tait and the LICAF team operate in other countries with their festivals was delightful. Julie advised PICOF (Philippines International Comics Festival), helping them to set up and get support through their government. She mentored them all through, and we attended their first in-person festival in Manila. It’s a fantastic event with a small-press focus and very LGBTQ+ friendly. The Philippines have historically been a very catholic country but people are finally expressing their queer identity and they’re choosing to do that through comics. It was one of the nicest festivals I’ve been to. Paolo Herras and Kris Porio, who run it, are just the loveliest people on earth. We also helped run LICAF’s Comics Can Change The World program. Going out to neighbourhoods to teach kids how to do four-panel comics. One of these was an NPO in a very low-income area. These kids have really hard lives, so we just wanted to give them an hour and a half to chill and draw some stuff. It was challenging, but they softened to the idea and in the end enjoyed the programme, especially when we gave them comics to keep to read and materials to draw their own comics.

LICAF is doing these kinds of things all over the world. I’ve been working with them to mentor a Palestinian artist on his experiences of being a refugee from Gaza, who left before the war, Khaled Jarada. His family is still there and has to deal with the current horrific situation, whilst Khaled is attempting to explore his experiences through comics. It’s a brilliant and necessary work that I hope will get realised and into readers’ hands soon. LICAF is also co-running a comics camp in Bethlehem, which I helped devise a program for, with Mollie going to teach. The theory is that comics can change the world through storytelling, and I do think there’s absolutely something in that.

A lot of comic festivals work together; they chat and help each other out, it’s that background stuff we don’t always see, and I love seeing that. How they’re run and how they get funding. I want to run a festival one day, maybe once I’ve moved to Brighton, so I want to know how they get funding and community support. Festivals allow us to elevate each other and pass on knowledge. It widens the community aspect of comics as well as locally, but also there is a professional aspect that brings more people into the industry. I’m really intrigued by that potential.

BIRD: You recently got to visit the Houses of Parliament on behalf of LICAF whilst the Comics Cultural Impact Collective was there to deliver a petition. What was that experience like?

SULLIVAN: We were there for very similar goals. They delivered their petition to gain funding for a national arts grant. Video games have government funding and a lobbyist group to get tax relief. The Comics Cultural Impact Collective wants to have something similar for comics. Their goal is creator-focused, trying to help people starting and those already working in comics. It is also a brilliant idea to create bursaries for people, and I hope there is some traction. LICAF was there because they have partnered with a new trade organisation, ComicBookUK, run by Mark Fuller, who works at Westminster with lobbyists. He noticed that no one was lobbying on behalf of comics, and there was no MP’s lobbyist group for that. He’s been working from within to bring in MPs such as Chris Bryant, the culture secretary, and Tim Farron, who submitted an Early Day Motion for debate supporting LICAF, ComicBookUK, and comics as an industry. I was there on behalf of LICAF, alongside festival patrons Sean Phillips, Charlie Adlard, and Bobby Joseph, the comics laureate. Avery Hill Publishing, Rebellion, and Arts Council England were there. At the moment, ComicBookUK is focused on working with publishers to export UK comics globally, as well as trying to get more funding bodies involved and lobbying for benefits such as tax breaks.

The two groups have similar goals but work differently towards them. CCIC is amazing, they’re all comics creators who are trying to get the truth about the state of the industry out, how badly we’re paid, and how many of us are only doing it part-time. They’re trying to change that for the better, which is really impressive and heartfelt, and I wish them all the best. LICAF is trying to get UK comics on a global stage and recognise its value in culture and literacy. Noble aims indeed. The more people shouting about comics, the better, as far as I am concerned.

BIRD: What do you want readers to take away from your work?

SULLIVAN: I’d really like to put people in the shoes of others’ experiences. I hope I can engender some empathy, especially in relation to the experiences that might be a little bit foreign to them. I have a lot of male readers – my last book, Shelter, has a scene of sexual assault after a woman is followed home, and so many male readers of mine have told me that they hadn’t considered what it would be like to be that woman. That part of the comic was born after I was going home one night and kept getting on the same train as this guy, and we got off at the same station and walked the same way home, so I thought, “Oh my god, he probably thinks I’m stalking him!” That led to me wanting to explore what would happen if someone did mean to do that. I always want my books to be entertaining, I love folklore so I love to put some of that into it, but mostly it’s about putting you in someone else’s shoes, and hopefully you’ll be open to it. I think that builds empathy. The more we understand about how others feel, the nicer we will be, the more caring we will be.

BIRD: Fantastic. Thank you so much for your time.

SULLIVAN: Thank you!